Tyrannosauroidea

| Tyrannosauroidea | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

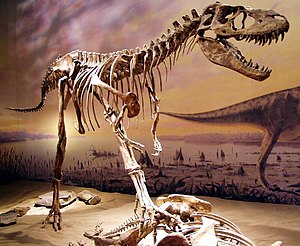

Skeleton reconstruction of Albertosaurus in the Royal Tyrrell Museum in Alberta |

||||||||||||

| Temporal occurrence | ||||||||||||

| Middle Jurassic to Upper Cretaceous ( Bathonian to Maastrichtian ) | ||||||||||||

| 168.3 to 66 million years | ||||||||||||

| Locations | ||||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||||

| Tyrannosauroidea | ||||||||||||

| Brown , 1914 | ||||||||||||

The Tyrannosauroidea is a superfamily of Coelurosaurier (Coelurosauria) within the theropod dinosaurs . It includes the Tyrannosauridae , which include for instance the well-known Tyrannosaurus rex belongs, as well as the basal, ie standing at the beginning of the development series types . Tyrannosauroids lived on the northern supercontinent Laurasia and first appeared in the Central Jurassic about 168 million years ago. In the Upper Cretaceous they were the dominant great predators of the northern hemisphere . Their fossils were discovered in North America , Europe, and Asia .

Tyrannosauroids, like most theropods, were bipedal carnivores . The group is characterized by numerous mutually derived features ( synapomorphies ), which are particularly found in the skull and pelvic bones. Early in their evolution, tyrannosauroids were small predators with long, three-fingered arms. Upper Cretaceous species grew significantly larger, including some of the largest terrestrial carnivores that have ever existed - but most of these late species had proportionally small arms with only two fingers. Primitive feathers are known from Dilong , an early tyrannosauroid from China , as well as from Yutyrannus, and were perhaps also present in other tyrannosauroids. Many species wore conspicuous ridges of bones in various shapes, perhaps for display purposes.

features

The body size varied considerably between the individual species, but in the course of evolution the group grew larger and larger. Early tyrannosauroids were still relatively small animals - adult specimens of Dilong measured 1.6 meters and Guanlong three meters in length. Cretaceous genera grew larger; a not yet sexually mature Eotyrannus was over four meters long and a not yet fully grown Appalachiosaurus was more than six meters long. Tyrannosaurids of the Upper Cretaceous, on the other hand, sometimes reached gigantic proportions. Albertosaurus and Gorgosaurus were both about nine meters long, and Tyrannosaurus was the largest known genus at over twelve meters in length and perhaps over 6,400 kilograms.

The skulls of early tyrannosauroids were long, low, and lightly built, resembling those of other coelurosaurs, while later forms had much taller and more massive skulls. Despite these differences, certain cranial features ( synapomorphies ) can be found in all previously known tyrannosauroids: The intermaxillary bone (premaxilla) was very high, which resulted in a blunt snout - a feature that also developed convergently in the Abelisaurids . The paired nasal bone was fused, slightly arched upwards and mostly very rough, often structured like a bark, on the upper side. The teeth of the intermaxillary bone on the front part of the upper jaw were smaller and differently shaped than the rest of the teeth and had a “D” -shaped cross-section. The lower jaw of all tyrannosauroids except Guanlong had a pronounced crest on the surangular , which extended laterally directly below the temporomandibular joint.

Tyrannosauroids, like most other theropods, had "S" -shaped necks and long tails. Early genera had three-fingered, long arms that reached 60 percent of the length of the hind legs in Guanlong . The long arms were characteristic of the group at least as far as the Lower Cretaceous, as Eotyrannus shows, but they have not been preserved in Appalachiosaurus . The arms of later tyrannosauroids were significantly shorter - especially with Tarbosaurus from Mongolia , whose upper arm bone ( humerus ) was only a quarter of the length of the thigh bone ( femur ). The third finger has also receded in the course of evolution: While it was not yet reduced in the basal guanlong , it was already significantly smaller than the other two fingers in Dilong . Eotyrannus still had three functional fingers on each hand; However, tyrannosaurids only had two fingers, although rudiments of a third finger were found in some specimens. As with most other coelurosaurs, the second finger was the largest.

Characteristic features in the pelvic bone include a notch of the lower end of the ilium ( ilium ), a clearly limited vertical comb on the ilium, extending from the hip joint socket stretched (acetabulum) upward, and the enlarged end of the pubis ( pubic bone ) with one that extended "T" -shaped on both sides and was more than half as long as the actual shaft of the pubic bone. These features are found in all known tyrannosauroids, including the basal genera Guanlong and Dilong . The pubic bone is unknown in Aviatyrannis and Stokesosaurus ; however, both genera show characteristics typical of tyrannosauroids in the iliac bone. The hind legs of all tyrannosauroids, like most theropods, had four toes, although the first toe (the hallux ) did not touch the ground. The hind legs of the tyrannosauroids were longer in relation to body size than in almost all other theropods and show proportions that are characteristic of fast-moving animals; thus the shinbone ( os tibia ) and the metatarsal bones were elongated. These proportions existed even in the largest known specimen of Tyrannosaurus , although these animals may not have been able to run. The upper half of the third (i.e., middle) metatarsal bone of the tyrannosaurids was "squeezed" between the other two metatarsals and had only a small portion of the contact area between the metatarsus and the tarsus - a structure known as the arctometatarsus . The Arctometatarsus was also found in Appalachiosaurus , but it is not clear whether it was also present in Eotyrannus or Dryptosaurus . This structure is found in ornithomimids , troodontids and Caenagnathids , but was not present in basal tyrannosauroids such as Dilong , which suggests convergent evolution .

Systematics

Tyrannosaurus was named along with the Tyrannosauridae family by Henry Fairfield Osborn in 1905. The name is derived from the ancient Greek words τύραννος / tyrannos ("tyrant") and σαῦρος / sauros ("lizard"). The name of the superfamily Tyrannosauroidea was first published by the British paleontologist Alick Walker in 1964. The ending -oidea , which is usually used for superfamilies in the animal kingdom, is derived from the ancient Greek εἶδος / eidos ("form").

Scientists mostly understood the Tyrannosauroidea as a taxon that included the Tyrannosauridae and their immediate ancestors. However, since the phylogenetic system was introduced into paleontology, the group received precise definitions. The first was established by Paul Sereno in 1998 and sees the Tyrannosauroidea as a taxon that includes all species more closely related to Tyrannosaurus rex than to neonatal birds . To describe the group even more exclusively, Thomas Holtz redefined it in 2004 to include all species more closely related to Tyrannosaurus rex than to Ornithomimus velox , Deinonychus antirrhopus, or Allosaurus fragilis . Sereno published a new definition in 2005 according to which all species of the Tyrannosauroidea belong to, which were more closely related to Tyrannosaurus rex than to Ornithomimus edmontonicus , Velociraptor mongoliensis and Troodon formosus .

classification

Superfamily Tyrannosauroidea

- ? Iliosuchus ( Central Jurassic , England )

- Aviatyrannis ( Upper Jura , Portugal )

- Stokesosaurus (Upper Jurassic, western United States )

- Dilong ( Lower Cretaceous , Eastern China )

- Eotyrannus (Lower Cretaceous, England)

- Moros (Lower Cretaceous, western United States)

- Raptorex (Lower Cretaceous, Eastern China)

- Xiongguanlong (Lower Cretaceous, China)

- Yutyrannus (Lower Cretaceous, China)

- Suskityrannus (Middle Cretaceous, United States)

- Timurlengia (Middle Chalk, Uzbekistan )

- ? Bagaraatan ( Upper Cretaceous , Mongolia )

- Dryptosaurus (Upper Cretaceous, eastern United States)

- Alectrosaurus (Upper Cretaceous, Mongolia)

- Appalachiosaurus (Upper Cretaceous, eastern United States)

- ? Labocania (Upper Cretaceous, western Mexico )

- Bistahieversor (Upper Cretaceous, western United States)

-

Family Proceratosauridae

- Kileskus (Middle Jurassic, Central Russia)

- Proceratosaurus (Central Jurassic, England)

- Guanlong (Upper Jurassic, western China)

- Sinotyrannus (Lower Cretaceous, Eastern China)

-

Family Tyrannosauridae

- Albertosaurus (Upper Cretaceous, western United States)

- ? Alioramus (Upper Cretaceous, Mongolia)

- Daspletosaurus (Upper Cretaceous, western United States)

- Dynamo Terror (Upper Cretaceous, New Mexico)

- Gorgosaurus (Upper Cretaceous, western United States)

- Lythronax (Upper Cretaceous, western North America)

- Qianzhousaurus (Upper Cretaceous, China)

- Tarbosaurus (Upper Cretaceous, Mongolia)

- Teratophoneus (Upper Cretaceous, United States)

- Tyrannosaurus (Upper Cretaceous, western United States)

- Zhuchengtyrannus (Upper Cretaceous, China)

Phylogenetics

In the 20th century, tyrannosaurids were usually considered to be representatives of the Carnosauria , which from the point of view of that time included almost all large theropods. Within this group, the allosaurids were often thought to be the ancestors of the tyrannosaurids. In the early 1990s, cladistic analyzes began to classify the Tyrannosauridae within the Coelurosauria , with the first assumptions being made as early as the 1920s. Tyrannosaurids are generally considered to be large coelurosaurs today.

In 1994 Holtz grouped the tyrannosauroids together with the Elmisaurids , the ornithomimosaurs and the troodontids in a new group within the Coelurosauria, which he called Arctometatarsalia . This group is based on the arctometatarsus, a structure in the metatarsal bones in which the second metatarsal bone is partially covered by the remaining two metatarsal bones when viewed from the front. Basal tyrannosauroids such as Dilong , however, did not show arctometatarsus, which suggests that this trait developed independently ( convergently ) several times in different groups . Therefore, the group Arctometatarsalia was discarded and no longer used by most paleontologists, whereby the Tyrannosauroidea is now mostly classified as a basal group of Coelurosauria outside of the Maniraptoriformes . A new analysis concluded that the Coeluridae family could have been the sister taxon of the Tyrannosauroidea.

The most pristine tyrannosauroid known from complete skeletal material is guanlong . Other early genera include Stokesosaurus and Aviatyrannis , but are known only from far less complete material. The better known Dilong is a bit more modern than Guanlong and Stokesosaurus . Dryptosaurus was long considered difficult to classify, but is now listed as a basal tyrannosauroid, which was somewhat more original than Eotyrannus and Appalachiosaurus . Alectrosaurus , a little-known genus from Mongolia, is definitely a tyrannosauroid, but its exact relationships are unclear. Other taxa have been suggested by some authors as possible tyrannosauroids, including Bagaraatan , Labocania, and a genus incorrectly assigned to the Chilantaisaurus , "C." maortuensis . Siamotyrannus from the Lower Cretaceous Thailand was originally described as an early tyrannosaurid, but is now considered a member of the Carnosauria. Iliosuchus shows a vertical ridge on the iliac bone, which is a feature of the tyrannosauroid. This genus could therefore actually be the earliest known representative of this superfamily, but this can only be confirmed by further bone finds.

distribution

The earliest known tyrannosauroids lived in the Middle Jurassic and include Guanlong from northwestern China, Stokesosaurus from the western United States, and Aviatyrannis from Portugal. Some fossils currently attributed to Stokesosaurus may belong to Aviatyrannis - the dinosaur faunas of Portugal and North America were actually very similar at the time. If Iliosuchus from the Central Jurassic of England was a tyrannosauroid, it would be the earliest known genus; this could indicate that the tyrannosauroids had their origin in Europe.

Lower Cretaceous tyrannosauroids were also found in all three northern continents. Eotyrannus from England and Dilong from northeast China are the only two genera named from this period; Furthermore, teeth of the intermaxillary bone are known from the Cedar Mountain Formation in Utah (United States) and from the Tetori group in Japan. "Chilantaisaurus" maortuensis from the Dashuigou Formation of Inner Mongolia in China is also sometimes considered to be an early tyrannosauroid of the Lower Cretaceous.

In Europe, tyrannosauroids have disappeared from fossil records since the Middle Cretaceous, suggesting a local extinction on this continent. Teeth and possible body fossils from the Middle Cretaceous are known from the North American Dakota Formation , as well as from formations in Kazakhstan , Tajikistan and Uzbekistan . The first indubitable remains of tyrannosaurids come from the Campanium (late Upper Cretaceous) of North America and Asia. This family is divided into two subfamilies, the albertosaurines were only found in North America, but the tyrannosaurines were discovered on both continents. Tyrannosaurid fossils were also discovered in Alaska , which may have been connected to Asia by a land bridge through which the faunas of North America and Asia could share. The tyrannosauroids Alectrosaurus and perhaps Bagaraatan are classified outside of the Tyrannosauridae, but lived with them in Asia at the same time while they were absent in North America. Since the Middle Cretaceous, eastern North America has been isolated from the western part of the continent by an arm of the sea, the Western Interior Seaway . Since tyrannosaurids were absent in the eastern part of the continent, it is believed that this family did not arise until after the arm of the sea divided the land. This allowed basal tyrannosauroids like Dryptosaurus and Appalachiosaurus to survive in eastern North America to the end of the Upper Cretaceous.

Paleobiology

feathers

Long fibrous structures have been preserved along with the skeletons of numerous coelurosaurs that come from the Lower Cretaceous of the Yixian Formation and other formations from Liaoning (China). These structures are commonly interpreted as "proto-feathers," homologous to the ramified feathers of modern birds, although other hypotheses have been made. A Dilong skeleton described in 2004 is the first known example of proto-feathers in tyrannosauroids. Similar to the down of modern birds, the proto feathers known from Dilong were branched, but they were not contour feathers . Possibly they were used for thermal insulation.

That proto-feathers were found in basal tyrannosauroids is not surprising, since feathers are considered a characteristic feature of the coelurosaurs. They are found in other basal genera such as Sinosauropteryx as well as in more modern genera. However, rare skin prints of large tyrannosaurids show no evidence of feathers, but instead a scaly skin. It is possible that proto-feathers were present on parts of the body that were not passed down through skin prints. Alternatively, the proto-feathers could have been lost in large tyrannosaurids, as the small area-volume ratio of these animals makes thermal insulation superfluous - similar to today's large mammals such as elephants . An exception here is Yutyrannus , in which filaments up to 20 centimeters long have been found that are interpreted as feathers.

Head combs

Bone ridges have been found on the skulls of many theropods, including numerous tyrannosauroids. The most spectacular example is guanlong , in which the pair of nasal bones supports a single, large ridge that runs along the center line of the skull from the muzzle to the back. The ridge was criss-crossed with large openings that reduced its weight. Less noticeable were the head ornaments of Dilong , which consisted of two low, parallel ridges that ran on each side of the skull and were supported by the nasal bone and tearbone . The combs curved inward just behind the nostrils, creating a "Y" -shaped structure. The fused paired nasal bone of the tyrannosaurids was often very rough textured. Alioramus , a possible tyrannosaurid from Mongolia, showed a single row of five conspicuous bony bumps on the nasal bone; a similar series with much smaller bumps is known from Appalachiosaurus and from some finds from Daspletosaurus , Albertosaurus and Tarbosaurus . The horn sitting on the tear bone is missing in Tarbosaurus and Tyrannosaurus , which instead had a crescent-shaped hood behind each eye on the postorbital bone . The head crests of the tyrannosauroids were probably used for display - perhaps for species recognition or for courtship.

Web links

- Tyrannosauroidea ( Memento from January 25, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) in The Theropod Database (English)

Individual evidence

- ^ Gregory S. Paul: The Princeton Field Guide To Dinosaurs , 2010. ISBN 978-0-691-13720-9 , pp. 99-110 Online

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Thomas R. Holtz Jr .: Tyrannosauroidea. In: David B. Weishampel , Peter Dodson , Halszka Osmólska (eds.): The Dinosauria . 2nd edition. University of California Press, Berkeley CA et al. 2004, ISBN 0-520-24209-2 , pp. 111-136.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k Xing Xu , Mark A. Norell , Xuewen Kuang, Xiaolin Wang, Qi Zhao, Chengkai Jia: Basal tyrannosauroids from China and evidence for protofeathers in tyrannosauroids. In: Nature . Vol. 431, No. 7009, 2004, pp. 680-684, doi : 10.1038 / nature02855 , PMID 15470426 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j Xing Xu, James M. Clark , Catherine A. Forster, Mark A. Norell , Gregory M. Erickson, David A. Eberth, Chengkai Jia, Qi Zhao: A basal tyrannosauroid dinosaur from the Late Jurassic of China. In: Nature. Vol. 439, 2006, pp. 715-718, doi : 10.1038 / nature04511 .

- ↑ a b c d Stephen Hutt, Darren Naish, David M. Martill, Michael J. Barker, Penny Newberry: A preliminary account of a new tyrannosauroid theropod from the Wessex Formation (Cretaceous) of southern England . In: Cretaceous Research. Vol. 22, No. 2, 2001, ISSN 0195-6671 , pp. 227-242, doi : 10.1006 / cres.2001.0252 .

- ↑ a b c d e Thomas D. Carr, Thomas E. Williamson, David R. Schwimmer: A new genus and species of tyrannosauroid from the Late Cretaceous (middle Campanian) Demopolis Formation of Alabama. In: Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. Vol. 25, No. 1, 2005, ISSN 0272-4634 , pp. 119-143, doi : 10.1671 / 0272-4634 (2005) 025 [0119: ANGASO] 2.0.CO; 2 .

- ↑ Elizibeth D. Quinlan, Kraig Derstler, Mercedes M. Miller: Anatomy and function of digit III of the Tyrannosaurus rex manus. In: The Geological Society of America. Abstracts with Programs. Vol. 39, No. 6, 2007, ISSN 0016-7592 , p. 77, abstract .

- ↑ a b c d Oliver WM Rauhut : A tyrannosauroid dinosaur from the Upper Jurassic of Portugal. In: Palaeontology. Vol. 46, No. 5, 2003, ISSN 0031-0239 , pp. 903-910, doi : 10.1111 / 1475-4983.00325 .

- ↑ Christopher A. Brochu, Richard A. Ketcham: Osteology of Tyrannosaurus rex. Insights from a nearly complete skeleton and high-resolution computed tomographic analysis of the skull (= Society of Vertebrate Paleontology. Memoir. 7, ISSN 1062-161X = Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. Vol. 22, No. 4, Supplement). Society of Vertebrate Paleontology, Northbrook IL 2002.

- ↑ John R. Hutchinson, Mariano Garcia: Tyrannosaurus was not a fast runner. In: Nature. Vol. 415, No. 6875, 2002, pp. 1018-1021, doi : 10.1038 / 4151018a , digitized (PDF; 279.67 KB) .

- ↑ Kenneth Carpenter , Dale Russell , Donald Baird, Robert Denton: Redescription of the holotype of Dryptosaurus aquilunguis (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Upper Cretaceous of New Jersey. In: Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. Vol. 17, No. 3, 1997, pp. 561-573, doi : 10.1080 / 02724634.1997.10011003 .

- ↑ a b c Thomas R. Holtz Jr .: The phylogenetic position of the Tyrannosauridae: implications for theropod systematics. In: Journal of Paleontology. Vol. 68, No. 5, 1994, ISSN 0022-3360 , pp. 1100-1117, abstract .

- ^ Henry Fairfield Osborn : Tyrannosaurus and other Cretaceous carnivorous dinosaurs. In: Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. Vol. 21, Article 14, 1905, pp. 259-265, digitized .

- ^ A b Alick D. Walker: Triassic reptiles from the Elgin area: Ornithosuchus and the origin of carnosaurs. In: Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences. Vol. 248, No. 744, 1964, ISSN 0080-4649 , pp. 53-134, doi : 10.1098 / rstb.1964.0009 .

- ^ Henry George Liddell , Robert Scott : A Lexicon abridged from Liddell and Scott's Greek-English Lexicon. 24th edition, carefully revised throughout. Ginn, Boston 1891 (Reprinted edition. Clarendon Press, Oxford 2010, ISBN 978-0-19-910207-5 ).

- ↑ a b José F. Bonaparte , Fernando E. Novas , Rodolfo A. Coria : Carnotaurus sastrei Bonaparte, the horned, lightly built carnosaur from the Middle Cretaceous of Patagonia (= Contributions in Science. No. 416, ISSN 0459-8113 ). Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Los Angeles CA 1990.

- ^ Paul C. Sereno : A rationale for phylogenetic definitions, with application to the higher-level taxonomy of Dinosauria. In: New Yearbook for Geology and Paleontology. Treatises. Vol. 210, No. 1, 1998, ISSN 0077-7749 , pp. 41-83.

- ^ Paul C. Sereno: Stem Archosauria. (No longer available online.) In: TaxonSearch Version 1.0. 2005, archived from the original on December 26, 2007 ; accessed on July 28, 2014 (English). Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Lindsay E. Zanno, Ryan T. Tucker, Aurore Canoville, Haviv M. Avrahami, Terry A. Gates & Peter J. Makovicky: Diminutive fleet-footed tyrannosauroid narrows the 70-million-year gap in the North American fossil record. Communications Biology volume 2, Article number: 64 (2019)

- ↑ Sterling J. Nesbitt, Robert K. Denton Jr, Mark A. Loewen, Stephen L. Brusatte, Nathan D. Smith, Alan H. Turner, James I. Kirkland, Andrew T. McDonald & Douglas G. Wolfe (2019). A mid-Cretaceous tyrannosauroid and the origin of North American end-Cretaceous dinosaur assemblages. Nature Ecology & Evolution. doi:

- ↑ Stephen L. Brusatte, Alexander Averianov, Hans-Dieter Sues, Amy Muir and Ian B. Butler (2016). New tyrannosaur from the mid-Cretaceous of Uzbekistan clarifies evolution of giant body sizes and advanced senses in tyrant dinosaurs. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences . doi: 10.1073 / pnas.1600140113

- ↑ Oliver WM Rauhut, Angela C. Milner , Scott Moore-Fay: Cranial osteology and phylogenetic position of the theropod dinosaur Proceratosaurus bradleyi (Woodward, 1910) from the Middle Jurassic of England. In: Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. Vol. 158, No. 1, ISSN 0024-4082 , 2009, doi : 10.1111 / j.1096-3642.2009.00591.x .

- Jump up ↑ Andrew T. McDonald, Douglas G. Wolfe, Alton C. Dooley Jr .: A New Tyrannosaurid (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Upper Cretaceous Menefee Formation of New Mexico. In: PeerJ. Vol. 6, 2018, e5749, DOI: 10.7717 / peerj.5749

- ↑ Mark A. Loewen, Randall B. Irmis, Joseph JW Sertich, Philip J. Currie , Scott D. Sampson: Tyrant Dinosaur Evolution Tracks the Rise and Fall of Late Cretaceous Oceans. In: PLoS ONE . Vol. 8, No. 11, 2013, e79420, doi : 10.1371 / journal.pone.0079420 .

- ↑ Junchang Lü, Laiping Yi, Stephen L. Brusatte, Ling Yang, Hua Li, Liu Chen: A new clade of Asian Late Cretaceous long-snouted tyrannosaurids. In: Nature Communications. 5, Article No. 3788, 2014, ISSN 2041-1723 , doi : 10.1038 / ncomms4788 .

- ^ Alfred Sherwood Romer : Osteology of the Reptiles. University of Chicago Press, Chicago IL 1956 (Reprint with new Preface and taxonomic Table. Krieger Publishing, Malabar FL 1997, ISBN 0-89464-985-X ).

- ↑ Jacques Gauthier : Saurischian monophyly and the origin of birds. In: Kevin Padian (Ed.): The Origin of Birds and the Evolution of Flight (= Memoirs of the California Academy of Sciences. Vol. 8). California Academy of Sciences, San Francisco CA 1986, ISBN 0-940228-14-9 , pp. 1-55.

- ↑ Ralph E. Molnar, Seriozha M. Kurzanov, Zhiming Dong : Carnosauria. In: David B. Weishampel, Peter Dodson, Halszka Osmólska (eds.): The Dinosauria. University of California Press, Berkeley CA et al. 1990, ISBN 0-520-06727-4 , pp. 169-209.

- ↑ Fernando E. Novas: La evolucion de los dinosaurios carnivoros. In: José L. Sanz, Angela D. Buscalioni (eds.): Los Dinosaurios y Su Entorno Biotico. Actas del Segundo Curso de Paleontologia in Cuenca (= Instituto Juan de Valdes. Series Actas Académicas. Vol. 4, ZDB -ID 1331351-4 ). Instituto Juan de Valdez, Cuenca 1992, ISBN 84-86788-14-5 , pp. 125-163.

- ^ William D. Matthew, Barnum Brown: The family Deinodontidae, with notice of a new genus from the Cretaceous of Alberta . In: Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. Vol. 46, No. 6, 1922, ISSN 0003-0090 , pp. 367-385, (PDF; 1.8 MB).

- ^ Friedrich von Huene : Carnivorous Saurischia in Europe since the Triassic. In: Geological Society of America Bulletin. Vol. 34, No. 3, 1923, ISSN 0016-7606 , pp. 449-458, doi : 10.1130 / GSAB-34-449 .

- ^ Paul C. Sereno: The Evolution of Dinosaurs. In: Science . Vol. 284, No. 5423, 1999, pp. 2137-2147, doi : 10.1126 / science.284.5423.2137 .

- ↑ a b c Oliver WM Rauhut: The interrelationships and evolution of basal theropod dinosaurs (= Special Papers in Palaeontology. Vol. 69). The Palaeontological Association, London 2003, ISBN 0-901702-79-X .

- ↑ Philip J. Currie, Jørn H. Hurum, Karol Sabath: Skull structure and evolution in tyrannosaurid dinosaurs . In: Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. Vol. 48, No. 2, 2003, ISSN 0567-7920 , pp. 227-234, (PDF; 137 kB).

- ↑ a b Mark A. Norell, James M. Clark, Alan H. Turner, Peter J. Makovicky , Rinchen Barsbold , Timothy Rowe : A new dromaeosaurid theropod from Ukhaa Tolgod (Ömnögov, Mongolia) . (= American Museum Novitates. No. 3545, ISSN 0003-0082 ). American Museum of Natural History, New York NY 2006, (PDF; 10.2 MB).

- ^ A b Phil Senter: A new look at the phylogeny of Coelurosauria (Dinosauria: Theropoda). In: Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. Vol. 5, No. 4, 2007, ISSN 1477-2019 , pp. 429-463, doi : 10.1017 / S1477201907002143 .

- ↑ Thomas R. Holtz Jr .: RE: Burpee Conference (LONG). In: Archives of the Dinosaur Mailing List. September 20, 2005, accessed July 29, 2014 .

- ↑ Eric Buffetaut , Varavudh Suteethorn, Haiyan Tong: The earliest known tyrannosaur from the Lower Cretaceous of Thailand. In: Nature. Vol. 381, No. 6584, 1996, pp. 689-691, doi : 10.1038 / 381689a0 .

- ^ A b Thomas R. Holtz Jr., Ralph E. Molnar, Philip J. Currie: Basal Tetanurae. In: David B. Weishampel, Peter Dodson, Halszka Osmólska (eds.): The Dinosauria. 2nd edition. University of California Press, Berkeley CA et al. 2004, ISBN 0-520-24209-2 , pp. 71-110.

- ↑ a b James I. Kirkland , Brooks Britt, Donald L. Burge, Kenneth Carpenter, Richard Cifelli, Frank DeCourten, Jeffrey Eaton, Steve Hasiotis, Tim Lawton: Lower to Middle Cretaceous Dinosaur faunas of the central Colorado Plateau: a key to understanding 35 million years of tectonics, sedimentology, evolution, and biogeography. In: Brigham Young University, Department of Geology. Geology Studies. Vol. 42, No. 2, 1997, ISSN 0068-1016 , pp. 69-103.

- ↑ Makoto Manabe: The early evolution of the Tyrannosauridae in Asia. In: Journal of Paleontology. Vol. 73, No. 6, 1999, pp. 1176-1178, abstract .

- ↑ Лев А. Несов: Динозавры Северной Евразии. новые данные о составе комплексов, экологии и палеобиогеографии. Санкт-Петербургский государственный университет, Санкт-Петербург 1995, digitized , (In English: Dinosaurs of Northern Eurasia online ). New data about assemblages (PDF , ecology and paleography 9 MB ).

- ^ Anthony R. Fiorillo, Roland A. Gangloff: Theropod teeth from the Prince Creek Formation (Cretaceous) of northern Alaska, with speculations on Arctic dinosaur paleoecology. In: Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. Vol. 20, No. 4, 2000, pp. 675-682, doi : 10.1671 / 0272-4634 (2000) 020 [0675: TTFTPC] 2.0.CO; 2 .

- ↑ a b Zhonghe Zhou , Paul M. Barrett , Jason Hilton: An exceptionally preserved Lower Cretaceous ecosystem. In: Nature. Vol. 421, No. 6925, 2003, pp. 807-814, doi : 10.1038 / nature01420 .

- ↑ a b Chen Peiji, Dong Zhiming, Zhen Shuonan: An exceptionally well-preserved theropod dinosaur from the Yixian Formation of China. In: Nature. Vol. 391, No. 6663, 1998, pp. 147-152, doi : 10.1038 / 34356 .

- ↑ Xu Xing, Zhou Zhonghe, Richard A. Prum: Branched integumental structures in Sinornithosaurus and the origin of feathers. In: Nature. Vol. 410, No. 6825, 2003, pp. 200-204, doi : 10.1038 / 35065589 .

- ↑ Theagarten Lingham-Soliar, Alan Feduccia , Xiaolin Wang: A new Chinese specimen indicates that "protofeathers" in the Early Cretaceous theropod dinosaur Sinosauropteryx are degraded collagen fibers. In: Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences. Vol. 274, No. 1620, 2007, pp. 1823-1829, doi : 10.1098 / rspb.2007.0352 .

- ^ Larry D. Martin , Stephan A. Czerkas: The fossil record of feather evolution in the Mesozoic. In: American Zoologist. Vol. 40, No. 4, 2000, pp. 687-694, doi : 10.1668 / 0003-1569 (2000) 040 [0687: TFROFE] 2.0.CO; 2 .

- ↑ Xing Xu, Kebai Wang, Ke Zhang, Qingyu Ma, Lida Xing, Corwin Sullivan, Dongyu Hu, Shuqing Cheng, Shuo Wang: A gigantic feathered dinosaur from the Lower Cretaceous of China. Supplementary information . In: Nature. Vol. 484, No. 7392, 2012, pp. 92–95, doi : 10.1038 / nature10906 , (PDF; 961 kB).