Johannes Hirschberger

Johannes Hirschberger (born May 7, 1900 in Österberg , Central Franconia ; † November 27, 1990 in Oberreifenberg ) was a German Catholic theologian, philologist, historian of philosophy and philosopher.

Life

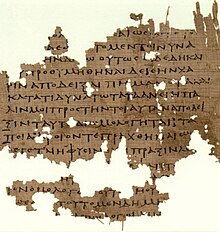

Hirschberger was born the son of a farmer. He attended the one-class elementary school for five years and graduated from high school in Eichstätt. After studying Catholic theology in Eichstätt , Hirschberger was ordained a priest on June 29, 1925. After that he was a year cooperator in Dollnstein and a year second cooperator in Berching . From February 16, 1927 he was studying philosophy , Greek philology and Catholic dogmatics at the University of Munich . From January 1, 1929 he worked as a cooperator in Gungolding , from November 1, 1929 as the second cathedral parish cooperator , from September 1, 1931 as an expat in Wasserzell . In 1930 he received his doctorate here with a thesis on Plato .

From August 16, 1933 to April 1, 1940 he was cathedral vicar and cathedral preacher in Eichstätt and from April 18, 1934 to November 1, 1939 he was a religious teacher at the local secondary school. On November 1, 1939, he became associate professor for the history of philosophy and practical philosophy at the Episcopal Philosophical-Theological College . From January 1, 1946, he was a full professor. On June 27, 1950, he was made an honorary citizen by his home community in Österberg . In 1953 he switched to the newly founded chair for Catholic religious philosophy at the University of Frankfurt . He stayed there until his retirement in 1968. During this time he was co-editor of the Philosophical Yearbook of the Görres Society and played a key role in founding the Cusanuswerk .

When he celebrated his golden jubilee as a priest on June 29, 1975, he was already the papal house prelate. He spent his retirement in Oberreifenberg . He was buried in Österberg.

He became famous for his history of philosophy in two volumes (1949–1952). It is considered a standard work in the history of philosophy and has been published over eighty times and has been translated into nine languages.

Act

Hirschberger wanted in his well-known history of philosophy not only history of philosophy represent but philosophize in a certain sense itself. According to his own information, he followed a metaphysical approach in his presentation that he had got to know from his neo-scholastic teacher Joseph Geyser in its “ideological-historical” form: Metaphysical theories and terms are examined and explained using ancient source texts. These are gradually upgraded within the framework of a specific translation tradition and tradition of interpretation. Passing on in tradition is a criterion for the truth value of theories and concepts. This corresponds to the Catholic-dogmatic view that divine truths develop historically in the theology of the church authorities. The idea of this approach was already effective in medieval scholasticism in connection with the assimilation of Aristotelian theories and ideas into the philosophy of Thomas Aquinas ( Neuthomism ).

| Reading sample |

|---|

| “While Descartes places the res cogitans next to the res extensa , Hobbes denies this dualism, also traces thought back to the res extensa and thus opts for a monistic materialism. Descartes' substance problem, which was given by the quality of the res cogitans and res extensa , was thus given a new solution. It was radical enough: Hobbes completely removes one side, that of the res cogitans . Now of course everything was much easier, probably too easy. " |

| History of Philosophy, Vol. 2, p. 189. |

Hirschberger applied this doctrine for Catholic theologians and philosophers, which was ordained by the Pope in the 19th century, to the research and presentation of the history of philosophy. The central theory of this approach to the history of ideas is therefore the philosophia perennis ; that is, the view that there is a timeless, consistent theme in the history of philosophy, namely the struggle for eternal truths . Under this point of view, Hirschberger described the success or failure, problems and errors of this struggle in connection with source-based representations of individual philosophies, philosophical directions and epochs. He wanted to achieve the highest level of objectivity and lack of preconditions. The encyclopedic quality of his history of philosophy has never been disputed. He admitted that an absolute measure could never be achieved and that every philosopher as a child of his time made unnoticed assumptions. He thought that what turned out to be timeless in terms of the history of ideas was objective and unconditional . He understood the actual history of philosophy as "the coming to itself of the human spirit". His approach shows a closeness to Hegel , but also to Christian theological ideas of the work of the Holy Spirit in history. He differs from Hegel's view of history by the assumption that the self-development of the spirit is not a straight path, but takes place through detours and errors which inevitably result from the imperfection of the respective philosophers.

As a consequence, he assessed philosophies according to the categories “true” and “false”. He positively rates philosophies that deal with both divine and human things. This was the distinguishing feature of philosophical science even in antiquity , he claimed. Philosophies that were limited to the tangible were rated negatively. He considered David Hume to be the most pronounced adversary of the self-development of the timeless spirit, because this had ushered in the temporary end of metaphysics . Representatives of metaphysical approaches, however, were praised. He described Leibniz as a “[...] thinker who stands above times and parties and who focuses on the eternally true in classic simplicity. [...] Philosophy [...] is for him exactly what Aristotle once wrote about it at the beginning of his metaphysics, love of wisdom, that wisdom that asks about the first and the original, about truth and about the good sake, as it corresponds to the metaphysical and ethical tradition of the West since Thales and Plato. "

The normative criteria for "correct" philosophizing that arise from Hirschberger's history of philosophy result from the assessment of historical methods with regard to whether they can and want to achieve eternal truths and objectivity. Hirschberger ascribes a “purifying” function to the history of philosophy, as it - according to the ideas of Neuthomism - should be oriented towards the history of ideas and metaphysically, i.e. tied to tradition and oriented towards eternal truths: “The best way to study philosophy of the present is in the past. If you don't, you only have the present, but no philosophy. "

The Hirschberg History of Philosophy was reissued a few years ago. It is recommended to students for self-study and as a reference book. The lack of other kinds of representations of the history of philosophy is seen as a disadvantage from a metaphilosophical point of view.

Works

- The phronesis in Plato's philosophy before the state . Leipzig 1932.

- Value and knowledge in the platonic symposium . In: PhJ 46 (1933), 201-227.

- History of philosophy as a critique of knowledge . In: A. Lang et al. (Ed.), From the Spiritual World of the Middle Ages (FS M. Grabmann), Münster 1935, 131–148.

- History of philosophy . Vol. I: Ancient and Middle Ages, Vol. II: Modern Times and Present, Freiburg 1949–1952 (15th edition 1991, Ndr. Frechen 1999), transl .: Spanish (2 vols., Barcelona 14th edition 1997), Portuguese ( 4 vols., São Paulo 1965-68), English (2 vols., Milwaukee 1958-59), Japanese (4 vols., Tokyo 1967-72), Korean (2 vols., Daegu 1983-87).

- Little history of philosophy . Freiburg 1961 (24th edition 1994).

- The god of the philosophers . in: N. Kutschki, God today. Fifteen contributions to the question of God, Mainz 1967, 11-19.

- Soul and body in late antiquity . Meeting reports of the Scientific Society of the Johann Wolfgang Goethe University Frankfurt, Main, Vol. VIII.1, Wiesbaden 1969.

- Similarity and analogy of being from the Platonic Parmenides to Proclus . In: B. Palmer / R. Hamerton-Kelly (Ed.), Philomathes. Studies and Essays in the Humanities in Memory of Philip Merlan, Den Haag 1971, 57-74.

- The position of Nikolaus von Kues in the development of German philosophy . Meeting reports of the Scientific Society of the Johann Wolfgang Goethe University Frankfurt, Main, Vol. XV.3, Wiesbaden 1978.

literature

- Kurt Flasch (Ed.): Parusia. Studies on the philosophy of Plato and the history of problems in Platonism. Ceremony for Johannes Hirschberger, Frankfurt a. M. 1965.

- Gangolf Schrimpf : Johannes Hirschberger in memory. in: Philosophisches Jahrbuch 99 (1992), 165–170.

- Bernd Goebel : HIRSCHBERGER, Johannes. In: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL). Volume 22, Bautz, Nordhausen 2003, ISBN 3-88309-133-2 , Sp. 546-549.

Web links

- Literature by and about Johannes Hirschberger in the catalog of the German National Library

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Ernst Baumgartl: History of the City of Greding . tape 5 , 1990, pp. 492-496 .

- ↑ So Hirschberger 1948 in his first foreword to the two-volume history of philosophy

- ↑ Johannes Hirschberger: History of Philosophy. Volume 1 , foreword and introduction.

- ↑ Ibid. Volume II , p. 149.

- ↑ Ibid. Volume II , p. 441.

- ↑ Kurt Flasch : Philosophy has a history. Volume 2. Theory of the History of Philosophy. Frankfurt am Main (Klostermann) 2005, p. 243f.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Hirschberger, Johannes |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German Catholic theologian and philosopher |

| DATE OF BIRTH | May 7, 1900 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Osterberg |

| DATE OF DEATH | November 27, 1990 |

| Place of death | Oberreifenberg |