John Colter

John Colter (* around 1774 near Staunton , Virginia , † November 1813 in Missouri ), also John Coulter , was an American trapper , mountain man and participant in several expeditions that explored the American West. His forays as a trapper took him repeatedly to areas previously unexplored by immigrants. Among other things, Colter is believed to be the first white man to discover the hot springs in what is now Yellowstone National Park . Some of his experiences went down in American myth- making. The best known is his experience racing against Blackfoot - Indians , inter alia, by authors such as Washington Irving has been processed literary.

Life

family

John's great-grandfather Micajah Coalter emigrated from Scotland to America around 1700 . Michael, Micajah's eldest son and John's grandfather, changed the name to Colter . Some family members also wrote to Coulter . The Colters acquired major lands near Staunton , Virginia , where John was born. Five years later they moved to Maysville , Kentucky .

Appearance

John Colter had blue eyes and was 178 cm tall. He was considered a shy, courageous person with a quick perception.

Lewis and Clark Expedition

John Colter answered on October 15, 1803 in Maysville as a private first class for the expedition of Meriwether Lewis and William Clark across today's USA . The participants in the expedition were selected according to strict criteria: They had to be good hunters, stout, healthy and unmarried men who were used to the woods and who could endure physical strain. Until the start on May 14, 1804, the participants were prepared for the trip near St. Louis , which they reached in December 1803. Colter never returned to Virginia. He received $ 5 a month for his service. However, the expedition participants were allowed to catch fur animals on the side and thus improve their wages.

Much of the trip took place on the river route. Colter was under the command of Sergeant John Ordway , who commanded the largest ship.

After Colter had to be disciplined at the beginning, he subsequently emerged as an excellent and reliable hunter. During his stroll through the woods, he met Indians of various tribes: Lakota , Mandan , Gros Ventre , Menominee , Nez Percé . He once surprised three Flathead Indians who were chasing two Shoshone for stealing 23 horses from them. Colter was able to persuade one of the Flathead to lead the expedition. The previous Indian leader, a Shoshone, was happy to return home, as they were now moving in foreign territory.

Colter distinguished himself through his tireless efforts during the strenuous expedition. He was in excellent physical condition, which made it possible for him and George Drouillard to hunt day after day as the only ones. His achievement for the expedition was honored by renaming a creek previously known as Potlatch Creek to Colter's Creek .

On November 7, 1805, the group reached the Pacific . After the winter she started her journey home.

Trappers

On August 15, 1806, Colter asked Captain Clark to be released. At a Mandan village they had met Joseph Dixon and Forrest Hancock , two trappers from Illinois , whom he wanted to join as partners. Clark complied and expressed great satisfaction with Colter's performance. Colter had made good use of the opportunity to supplement his wages by hunting fur and now exchanged his captured skins for the necessary equipment for two years. The three said goodbye south toward the Yellowstone River .

They spent the winter in a shelter . Colter used this time to explore the area.

Since beaver fishing was not very productive in this region and Colter had differences of opinion with his partners, he parted with them in the spring. Colter drove down the Yellowstone River to the Missouri River . There he met the Missouri Fur Company's Lisa and Drouillard expedition, which included three former colleagues from the Lewis and Clark expedition: George Drouillard, John Potts and Peter Weiser. Manuel Lisa , the leader of the fur trade expedition, was able to win over John Colter to take part in the 42-person expedition, which consisted mostly of French Canadians. Hancock later also joined. It is uncertain whether Dixon was also there.

While the expedition traveled unmolested through the areas of the Lakota, Arikaree , Mandan and Hidatsa Indians, there were confrontations with Indians in the Assiniboine area , which could, however, be resolved peacefully.

Once at the Yellowstone River, the expedition turned to it. In October 1807 she reached the confluence of the Bighorn River . In November, the participants built a log cabin there on the territory of the Absarokee Indians, which they named after Lisa's son Fort Raymond . Fort Raymond, sometimes also called Manuel's Fort, was the first building in what would later become the state of Montana and was intended to serve as a trading post. Lisa sent his trappers - including Colter - to make the trading post known to the neighboring tribes. Colter's over 500 mile tour took him into what is now Yellowstone and Grand Teton National Parks .

Exploring the Yellowstone area

Colter's route cannot be conclusively reconstructed. Presumably it first penetrated the Stinkingwater River (today: Shoshone River ), in an area characterized by volcanic activity, which became known as Colter's Hell . Then he crossed what is now Grand Teton National Park, bypassed Jackson Lake and moved further north, where he met Yellowstone Lake . He bypassed this in the northwest and followed the Yellowstone River to Tower Fall , possibly even to Mammoth Hot Springs . He then returned to Fort Raymond with a detour to Colter's Hell, where he arrived in the late spring of 1808.

He had undertaken much of his march in winter. While searching for Indian tribes, he had repeatedly made detours in different directions. He had certainly visited an Absarokee village. At times he had taken on the services of Indians who led him through difficult terrain.

After a break, Lisa sent him to the Blackfoot area. Colter joined a group of several hundred Absarokee and Flathead Indians en route. On the Gallatin River , they were attacked by what is believed to be an even larger Blackfoot group, traditionally an enemy of the Absarokee. Colter helped his companions repel the attack and was wounded in the leg in the process. For the rest of the fight he could only fight back by crawling. The defeated Blackfoot attacked whites again and again for the next fifty years because - in the face of Colter's involuntary involvement against them - they were convinced that the whites had allied themselves with the Absarokee. Colter broke off his trip and returned to Fort Raymond.

The race against the Blackfoot Indians

After his wound healed, Colter went back to catch beavers. Probably on the second fishing tour in the area of the Blackfoot Indians John Potts accompanied him. In doing so, they experienced an adventure that was told over and over again in the West in a wide variety of ways. The actual course of events is still controversial, but may have happened as follows:

When Colter and Potts searched their traps one morning in a canoe in the Jefferson River , they were surprised by a few hundred Blackfoot Indians and asked to moor. Colter threw his traps into the water and paddled to the bank, where the Blackfoot immediately grabbed him and tore his clothes off his body. When Potts saw this, he refused to steer his canoe ashore. An Indian shot an arrow at him and seriously injured Potts. This shot back and fatally hit an Indian, whereupon he was killed by several arrows. The Blackfoot pulled his body onto the bank and dismembered it. The relatives of the killed Indian could only be prevented with difficulty from attacking Colter. The Blackfoot directed him to run for his life. Even though Colter had to run naked and barefoot, he was able to fight for a head start. It was about five miles to the Madison River . A single Indian had broken out of the crowd of the running Blackfoot and was on Colter's heels. He suddenly stopped, snatched the spear from the Blackfoot and stabbed him with it. He quickly grabbed the cover and jumped into the river. Before the Indians approached, he could hide in a beaver den, where he stayed until late at night. Then he made his way back, bypassed the nearby pass by climbing a high mountain, ate only roots and tree bark for days, and after a march of about 500 km to the northeast, he arrived at the fort, completely exhausted.

It is certain that Colter and Potts fought with the Blackfoot, that Colter brought an Indian blanket with him to Fort Manuel and that the Blackfoot brought the captured skins to a trading post.

Return to civilization

The following winter, Colter revisited the site of the fight to retrieve the precious traps that were thrown in the water. As soon as he got there, he was heavily shot at by Indians and successfully fled again.

For the next few months, Colter acted as a trapper. At least once he led a group to Colter's Hell. In between he visited Indian villages, especially the Mandan and Hidatsa.

Probably in March 1810 led Colter, a group of 32 men in the area of Three Forks , the headwaters of the Gallatin-, Madison and Jefferson Rivers to build a new trading post. On the way they were caught in a snow storm. The situation became critical. Due to their snow blindness , they could not hunt game for days and had to eat three dogs and two horses. Suddenly 30 Blackfoot men appeared, but Colter's helpless group did not attack. After the expedition had crossed the place where Colter ran for his life, they reached the headwaters of the three rivers on April 3, 1810. There, in the middle of Blackfoot territory, they set up a palisade-protected camp. While Colter then led part of the group to the first catches, the camp was attacked by Gros Ventre Indians. Both sides suffered deaths. Through this event Colter realized that there were only two alternatives for him: to live in the west in constant fear of the Indians, especially the Blackfoot, or to return to the east. He decided to leave the area forever. The later death of his longtime comrade George Drouillard proved him right. Together with the young William Bryant ( the young Bryant of Philadelphia ) he left the camp. Shortly afterwards they were attacked by Blackfoot Indians, but were able to escape into the thicket.

Colter arrived in St. Louis in May. He only earned disbelief for his stories.

Retirement

John Colter did not stay long in St. Louis, but settled north of Charette, near what is now Dundee in Franklin County , Missouri. He hunted beavers there, as did Daniel Boone , who also lived in Charette. Sometime between May 1810 and March 1811, Colter married a woman named Sally. Presumably they had a son named Hiram.

In November 1813, John Colter died of jaundice on his Missouri farm . Two years later, Sally married a man named James Brown. In September 1889, three hunters found a large pine tree on Coulter Creek with an X and "JC" below it. They suspected that Colter had put the mark 80 years earlier and reported the find to authorities. They had the tree felled to display the section with the initials in a museum. However, it was lost during transport. In 1931, the farmer William Beard and his son found near Tetonia ( Idaho ) a magma stone that had been carved by hand to form a human head and the words " John Colter in 1808 was". The Colter Stone can be viewed today at the Moose Visitor Center in Grand Teton National Park.

Aftermath

There were a number of startling stories about Colter during his lifetime. Contrary to many stories, he probably only killed one Indian, a Blackfoot. Even today it is unclear to what extent many stories correspond to the actual circumstances. Escape from the Blackfoot, in particular, was a popular story that has been told by various authors. The first to write it down was Henry Brackenridge , who had heard it directly from Colter at Fort Manuel. Other authors later took it over, for example Washington Irving in "Astoria" in 1836 .

Colter's merits lie primarily in his achievements in the Lewis and Clark expedition, in his ability to forge relationships with the most diverse Indian peoples and in the subsequent explorations in areas previously unknown to the whites. In 1814, William Clark Colter's information was included in his sketch of a first map of the American West, as Colter had explored a number of mountain ranges during his forays that Clark was not aware of.

In memory of his escape from the Blackfoot Indians, the John Colter Run takes place annually in the headwaters of the Missouri River .

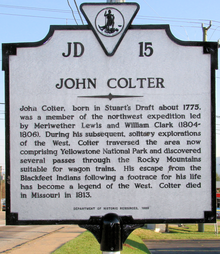

On September 6, 2003, the city of New Haven , Missouri, opened a museum about John Colter. There is a plaque near his birthplace in Virginia, on US Route 340 just north of the intersection with US Route 608 .

Various geographic features are named after Colter, such as Colter Bay in Grand Teton National Park and Colter Peak in the Absaroka Range , both in northwest Wyoming.

In the novel Hart auf Hart by the author TC Boyle (Original: The Harder They Come ) from 2015, Colter plays an important role as a figure to identify with the protagonist Adam. In Chapter 19, Colter's Blackfeet encounter is retold.

literature

- Burton Harris: John Colter - His Years in the Rockies. Charles Scribner's Sons, New York 1952. ISBN 0-8032-7264-2

- Aubrey L. Haines: The Yellowstone Story. A History of our first National Park. 2 Vols. University Press of Colorado, Niwot Col 1996. ISBN 0-87081-390-0 , ISBN 0-87081-391-9

- Mark H. Brown: The Plainsmen of the Yellowstone. A History of the Yellowstone Basin. GP Putnam's Sons, New York 1961. ISBN 0-8032-5026-6

Web links

- National Park Service: John Colter (Eng.)

- John Colter Run (Engl.)

Individual evidence

- ^ The Harder They Come , Ecco, New York 2015, ISBN 978-0-06-234937-8 . In German: Hart auf Hart . From the American by Dirk van Gunsteren, Carl Hanser Verlag, Munich 2015, ISBN 978-3-446-24737-6 .

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Colter, John |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Coulter, John |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | American trapper, member of the Lewis and Clark expedition, explorer of Yellowstone National Park |

| DATE OF BIRTH | around 1774 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Virginia , USA |

| DATE OF DEATH | November 1813 |

| Place of death | Missouri , USA |