Hersbruck subcamp

The Hersbruck subcamp (code name: Dogger , B 7 ) was the second largest subcamp of the Flossenbürg concentration camp and existed from May 17, 1944 to April 1945. It was a labor camp that was and was set up as part of the safeguarding of Nazi arms production on the eastern outskirts of the small town of Hersbruck in Central Franconia .

Historical background

When the Second World War broke out in September 1939, the Third Reich's Air Force was one of the strongest air forces in the world and enabled the Nazi regime to achieve numerous military successes at the beginning of the war. During the first two years of the war it was able to secure air control over the German sphere of influence and thereby prevent almost all enemy attempts to impair the German armaments industry . With the attack on the Soviet Union in June 1941, however, many important air force units were relocated to the newly formed Eastern Front. At first these shifts were barely noticeable, but when the USA entered the war in December 1941 at the latest , a change in the balance of power in German airspace began to appear.

In the course of 1942 the Allies were able to inflict various damage on German war production in the air war and in the following year of the war the Allied air superiority grew stronger and stronger. By the beginning of 1944, the Allied air forces finally achieved air control over Germany and all of Central Europe, so that they could attack every German manufacturing facility for war-essential goods within range of their strategic bomber fleets. After the British bombing of Peenemünde , the U relocation began, with the most important production facilities of the war economy being moved underground . Due to the lack of suitable underground vaults, the Reich Ministry for Armaments and War Production, headed by Albert Speer , had the necessary underground areas built by forced laborers employed en masse .

The creation of the Hersbruck satellite camp

When looking for suitable locations for the construction of underground production facilities, the Houbirg, south of the Pegnitz , soon came into the focus of the Nazi armaments planners. This striking mountain, located directly to the east of the village of Happurg , was relatively well suited for driving tunnels because of its very soft and therefore easy-to-work sandstone layer, known as Dogger . The terrain was also easily accessible from the Nuremberg – Schwandorf railway line , which runs along the northern foot of the Houbirg. Another advantage was the vacant barracks of the Reich Labor Service (RAD) , which was five kilometers to the west on the eastern edge of the small town of Hersbruck and in the immediate vicinity of the Nuremberg – Cheb railway line . So the choice was made for the interior of the Houbirg mountain as the location for a new underground armaments factory to be built. With the construction of this factory, the further production of aircraft engines by the BMW company should be ensured, which until then had been produced in Allach near Munich, which was meanwhile strongly endangered by air attacks .

In the spring of 1944, the former RAD barracks was therefore set up as a command and accommodation quarters for units of the SS , whose task it was to develop the surrounding area into a concentration camp. Simple barracks were built on the resulting camp grounds as accommodation for the concentration camp inmates who were supposed to build the tunnel system for the underground factory. The entire area was secured with watchtowers and electric fences against possible escape attempts by the prisoners and assigned to the main camp Flossenbürg as a satellite camp. To guard the camp complex and the construction site in the Houbirg, the SS stationed around 400 men on the camp grounds.

The construction work for the underground armaments factory in the Houbirg

In April 1944, the first concentration camp inmates from the main camp arrived in Hersbruck, and in the following month work began on the building project, which the planners had given the code name Doggerwerk . A narrow-gauge railway has been created by Hersbruck from that led to below the Houbirg and from there via the switchback climbed the mountain. A regular-gauge branch line was also built from Pommelsbrunn station up to Houbirg. About halfway along the route there was a reloading point from which building materials were loaded onto a cable car. The prisoners usually walked the five kilometers from the barrack camp in Hersbruck and worked in two shifts. After the completion of the final expansion, the facility would have had a tunnel length of 18 kilometers and a floor area of 120,000 square meters, which should be accessible via a total of eleven entrances, whereby the construction costs for the year 1944 alone were estimated at 15 million Reichsmarks . After the construction work began, more and more prisoners arrived in the labor camp over the course of the following months, by the summer of 1944 it had been around 2000, a total of around 9,500 concentration camp prisoners were probably brought to the Hersbruck camp, more than Hersbruck residents at the time even though it was only planned for 2000 inmates. These came from 23 different nations, the largest group being Hungarian Jews, followed by Soviet, Polish, Italian and French prisoners of war.

Under the guidance of around 400 German miners, the prisoners were forced to work in shifts and under the most difficult working conditions to build the mining tunnels required for the planned armaments factory. The prisoners were requested by the companies involved in the construction project from the SS, who then paid a so-called loan fee for their use . Until the camp was closed, a tunnel system with a total length of 3.5 kilometers was built and an overburden of 500,000 cubic meters of sandstone was removed from the Houbirg mountain. Within a year, a cave system was created, which consisted of eight huge longitudinal and cross passages, which widened like a hall to a width of ten and a height of six meters.

The victims of the Hersbruck satellite camp

In contrast to the six extermination camps, the Hersbruck subcamp was not a real Nazi death factory, but the death rate among concentration camp inmates was just like in many other labor camps - in line with the Nazi motto of annihilation through work - also very high here. And that, although the Nazi armaments planners should have wanted the underground armaments factory to be completed as quickly as possible and thus there was also a certain interest in maintaining the labor of the prisoners required at least until the underground factory was completed. However, due to the harsh working conditions and difficult living conditions in the Hersbruck subcamp and its surroundings, around 2,640 inmates who were forced to do compulsory labor died here. Many other prisoners died after they were transferred back to the Flossenbürg concentration camp due to illness or when they were forced to go on death marches towards the Dachau concentration camp after the Hersbruck camp was evacuated in early April 1945 . In total there were at least 4,000 prisoners who did not survive their work in the Hersbruck satellite camp.

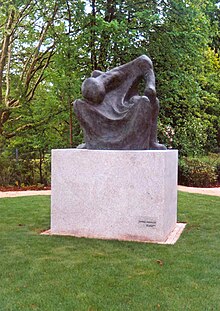

Because of the numerous fatalities, the camp management had a crematorium built by the Kori company southeast of Happurg , in which the corpses of the prisoners who had died were cremated. The concentration camp memorial near Förrenbach , built at the beginning of the 1950s and reminiscent of the location of the crematorium, had to be relocated in 1955 because otherwise it would have been flooded by the damming of Lake Happurger See .

After the capacity of the crematorium, which is now at the bottom of the reservoir, was no longer sufficient to remove the ever-growing piles of corpses, the camp management had some of the prisoners' corpses burned in remote places in the wild. The concentration camp memorial near Schupf commemorates one of these places; more than 1,000 corpses were cremated here in the winter of 1944/1945. When this improvised cremation site was no longer sufficient, around 300 corpses were cremated in a wooded area near the hamlet of Hubmersberg on a November night in 1944 . The memory of this event is kept alive today by the concentration camp memorial near Hubmersberg .

The end of the camp and its aftermath

With the almost non-fighting occupation of the city of Hersbruck by American troops in April 1945, the existence of the Hersbruck subcamp, which had already been largely evacuated, ended. In the post-war period, the memory of the concentration camp facility located there was very quickly pushed out of public awareness or deliberately abandoned to oblivion. In 1951, the barracks on the former concentration camp site were demolished, and later a housing estate and tennis court were built on this site. In contrast, the former RAD barracks, used as the headquarters and accommodation for the SS guards, existed for more than five decades. In this wing of the building there was initially a school and later the tax office of the district of Nürnberger Land . In 2007 this remnant of the camp site was also demolished and replaced by a new building. The tragic history of this square is only commemorated today with a small information board that is clearly separated from the entrance area of the newly built tax office.

The memory of the Dogger factory, which was no longer completed, was also quickly eliminated in the post-war years. The tunnel entrances, which were still accessible until then, were concreted over in the 1960s, but without any indication of the type of construction of these tunnels. It was not until 1998 that a memorial plaque was finally attached to one of these tunnel entrances, on which the background for its creation is mentioned.

The author Bernt Engelmann , once imprisoned here himself, wrote a preface to Gerd Vanselow's specialist work: “That is exactly what ... we once hoped for, we, the prisoners of the Hersbruck camp in 1944/45: that our many dead and we few survivors would not forget that someone would research and write down what happened day after day in front of the eyes of the population of the small town on the Pegnitz. "

literature

- Horst M. Auer (Ed.): Location history Franconia , volume 2. Ars Vivendi Verlag GmbH, Cadolzburg 2002. ISBN 3-89716-316-0 .

- Gerhard Faul: slave labor for the final victory. Hersbruck concentration camp and the Dogger armaments project. Hersbruck 2003.

- Hans-Friedrich Lenz: Tell Pastor, how did you get into the SS? - Report of a pastor of the confessing church about his experiences in the church fight and as SS-Oberscharführer in the concentration camp Hersbruck. Giessen / Basel 1982.

- Elmar Luchterhand: The concentration camp in the small town. Reminder of a community of the unsystematic genocide. In Detlev Peukert , Jürgen Reulecke (Ed.): The ranks almost closed. Contributions to the history under National Socialism. Wuppertal 1981, pp. 435-454.

- Nuremberg country . Karl Pfeiffer's Buchdruckerei und Verlag, Hersbruck 1993. ISBN 3-9800386-5-3 .

- Alexander Schmidt: The Hersbruck subcamp and its perception in the Nuremberg region after 1945 in the Bavarian State Center for Political Education (ed.): Traces of National Socialism. Memorial work in Bavaria. Munich 2000, pp. 150-162.

- Alexander Schmidt: The Hersbruck subcamp. On the history of the largest satellite camp of the Flossenbürg concentration camp in Bavaria. In Dachauer Hefte 20, 2004, pp. 99–111

- Franz Thaler : Unforgettable. Option, concentration camp, captivity, homecoming. A Sarner tells. Edition Raetia, Bozen 1999. ISBN 88-7283-128-8 .

- Gerd Vanselow: Hersbruck concentration camp. Largest sub-camp of Flossenbürg. 3rd edition Hersbruck 1992 (first Hersbruck 1983)

- Regional Court of Nuremberg-Fürth, July 13, 1950 . In: Justice and Nazi crimes . Collection of German criminal judgments for Nazi homicidal crimes 1945–1966, Vol. VI, edited by Adelheid L. Rüter-Ehlermann, HH Fuchs, CF Rüter . Amsterdam: University Press, 1971, No. 223, pp. 695–722. Ill- treatment of prisoners, sometimes resulting in death, as well as shooting of a prisoner for stealing potatoes. Shooting of prisoners in Schwaighausen during the evacuation march from KL Hersbruck to KL Dachau

Web links

- Hersbruck subcamp

- Documentation location Hersbruck / Happurg

- Documentation Center Concentration Camp Hersbruck e. V.

- Location of the former Hersbruck satellite camp in the BayernAtlas (accessed on October 16, 2016)

Individual evidence

- ^ Happurg and Hersbruck . In: Wolfgang Benz , Barbara Distel (eds.): The place of terror . History of the National Socialist Concentration Camps. Volume 4: Flossenbürg, Mauthausen, Ravensbrück. CH Beck, Munich 2006, ISBN 3-406-52964-X , here p. 136.

- ↑ Hersbruck satellite camp. Website of the Flossenbürg Concentration Camp Memorial. Retrieved July 6, 2016.

- ^ Vanselow: Hersbruck Concentration Camp. Largest sub-camp of Flossenbürg. 3rd edition Hersbruck 1992

- ↑ Bernt Engelmann: Almost forgotten: Hersbruck concentration camp hidden somewhere in the forest. In: Die Zeit , November 4, 1983. Retrieved July 9, 2016.

Coordinates: 49 ° 30 ′ 43 " N , 11 ° 26 ′ 37" E