Kollektaneenbuch

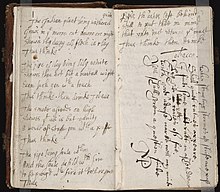

A Kollektaneenbuch (also Kollektanee) is an individual handwritten compilation of information in a book. Collector tans have been handed down from antiquity and were mainly preserved in the Renaissance and the 19th century . They were filled with different elements: recipes, quotes, letters, poems, weight and measurement tables, idioms, prayers, legal formulations. Kollektaneen have been used by readers, authors, students, and scholars as a tool to help them recall useful concepts and facts. Each book is unique due to the special interests of its creator, but you will almost always find passages from other texts in them, sometimes accompanied by reactions or comments. They gained importance in the early modern period .

His English term "Commonplace" is a translation of the Latin term locus communis (from the Greek tópos koinós , see topos ) which means something like "a general or everyday topic", like the statement of a proverbial wisdom. In this original sense, collections of proverbs are collections of proverbs, like the example of John Milton . For scholars today, they include manuscripts in which a person gathers materials that examine a particular subject such as ethics or various subjects in a volume. Kollektaneen are private collections of information, but not diaries or travel reports .

In 1685, the English Enlightenment philosopher John Locke wrote a treatise on Collektaneen in French, which was translated into English in 1706 under the title A New Method of Making Common-Place-Books . In it, he described techniques for capturing proverbs, quotations, ideas and speeches. In addition, he gave specific advice on how to organize materials by topic and category using key themes such as love, politics or religion. It must be emphasized that collectans are not chronological and introspective diaries.

In the 18th century they became a means of information management by jotting down quotations, observations, and definitions. They were used in private households to collect ethical or informative texts, sometimes alongside prescriptions or medical prescriptions. For women excluded from formal higher education, a Kollektaneen book could be a source of intellectual references. The noblewoman Elizabeth Lyttelton led one of the 1670 to 1713 and a classic example, which headings such as Ethical fragment (German: ethical fragments) Theological (German: Theology) and Literature and Art (German: Literature and Art) included , was of Anna Jameson published in 1855. Kollektaneen were used by researchers and other thinkers just as databases are used today: Carl Linnaeus , for example, used these techniques to create and organize the nomenclature of his Systema Naturae (which forms the basis of systems used by researchers today). A collection book was often a lifelong habit: for example, the Anglo-Australian artist Georgina McCrae kept one from 1828 to 1865.

history

Early examples

The forerunners of the Kollektaneen were the records of Roman and Greek philosophers about their thoughts and daily meditations. Quotes from other thinkers were also often included. The practice of keeping such a book was particularly recommended by Stoics such as Seneca and Marcus Aurelius , whose own work Meditations was originally a private record of thoughts and quotes. The pillow book by Sei Shonagon , a lady-in-waiting from Japan in the 10th and 11th centuries is also a private book with anecdotes and poems, everyday thoughts and lists. However, none of these works contain the range of sources normally associated with Kollektaneen. A number of scholars of the Renaissance carried something that resembled Kollektaneen - for example Leonardo da Vinci , who designed his notebook exactly like a Kollektaneen book is structured: "A collection without order, drawn from many papers, which I have copied here, hoping to arrange them later each in its place, according to the subjects of which they treat ", German: A collection in no order, drawn from many works that I have copied here, in the hope of being able to sort them later which they belong according to their subject matter.

Zibaldone

During the 15th century, the Italian peninsula was the scene of the development of two new forms of book production: the luxury register book and the zibaldone. What made the two different was their compositional language: a dialect. Giovanni Rucellai , the author of one of the most sophisticated examples of the genre, described it as "salad of many herbs".

Zibaldone have always been small or medium-sized paper codes - never the large desk copies of the register book or any other textbook. They also lacked the inner lining and the extensive decoration of other luxury copies. Instead of miniatures, a zibaldone would often use the author's sketches. It contained cursive scripts and what the paleographer Armando Petrucci described as an astonishing variety of poetic and prosaic texts. Devotional, technical, documentary, and literary texts appeared side-by-side in no discernible order. The juxtaposition of taxes, exchange rates, medical supplies, prescriptions and favorite quotes shows an evolving secular, literary culture. By far the most popular literary selection were the works of Dante Alighieri , Francesco Petrarca and Giovanni Boccaccio : the "three crowns" of Florentine folk tradition. These collections were used by modern scholars as a source of interpretation of how merchants and artisans interacted with literature and the visual arts in the Florentine Renaissance.

The best known Zibaldone is Giacomo Leopardi 's Zibaldone di pensieri from the 19th century.

English

By the 17th century, Kollektaneen had become a recognized practice officially taught to students in institutions such as Oxford University. John Locke attached his indexing scheme for collection books to a copy of his treatise An Essay Concerning Human Understanding . The Kollektaneen tradition in which Francis Bacon and John Milton were taught had its origins in the pedagogy of classical rhetoric and "commonplacing" persists as a popular study technique into the early 20th century. Kollektaneen were used by many key Enlightenment thinkers , such as authors such as the philosopher and theologian William Paley to write books. Both Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau were trained at Harvard University to keep a collective book (their books have survived in published form).

Yet it was also a domestic and private practice that was particularly appealing to writers. Some, like Samuel Taylor Coleridge , Mark Twain, and Virginia Woolf , kept chaotic reading notes mixed with other very different materials; others, like Thomas Hardy , followed a more formal method of reading notes that was more in keeping with the original Renaissance practice . The older, "clearinghouse" function of the collection book, to summarize and centralize useful and even "exemplary" ideas and expressions, has become less widespread over time.

Manuscript examples

- Zibaldone da Canal (New Haven, CT, beincke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, MS 327)

- Robert Reynes of Acle, Norfolk (Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS Tanner 407).

- Richard Hill, a London grocer (Oxford, Balliol College, MS 354).

- Glastonbury Miscellany. (Trinity College, Cambridge, MS 0.9.38). Originally designed as a business book.

- Jean Miélot , Burgundian translator and author of the 15th century. His book is in the French National Library and is the main source for his verses, many of which were written for court occasions.

- Adelaide Horatio Seymour Spencer, a 19th century lady-in-waiting. Located in the Franklin Library, University of Pennsylvania.

- Virginia Woolf , 20th century writer. Some of her notebooks are in Smith College, Massachusetts.

Published examples

- Francis Bacon , "The Promus of Forms and Elegancies," Longman, Greens and Company, London, 1883. Bacon's Promus was a crude listing of elegant and useful phrases gleaned from reading and conversation that Bacon used as a source for writing and probably as a memo book for oral practice in public speaking.

- John Milton , "Milton's Commonplace Book," in John Milton: Complete Prose Works , gen. Ed. Don M. Wolfe (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1953). Milton kept scientific notes of his readings, including page numbers, for use in writing his tracts and poems.

- The Commonplace Book of Elizabeth Lyttelton (Cambridge University Press, 1919)

- Mrs Anna Anderson, A Common Place Book of Thoughts, Memories and Fancies ( Longman, Brown, Green and Longman, 1855 )

- EM Forster , "Commonplace Book," ed. Philip Gardner (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1985).

- WH Auden , A Certain World (New York: The Viking Press, 1970).

- HP Lovecraft : Commonplace Book . In: HP Lovecraft's Commonplace Book , Wired , July 4, 2011. Retrieved July 5, 2011. Translated by Bruce Sterling .

- Robert Burns , " Robert Burns's Commonplace Book. 1783-1785. " James Cameron Ewing and Davidson Cook. Glasgow: Gowans and Gray Ltd., 1938.

Literary references

- In Lemony Snicket 's A Series of Unfortunate Events , a variety of characters including Klaus Baudelaire and the Quagmire triplets keep a collector's book.

- In Michael Ondaatje 's The English Patient , Count Almásy uses his copy of Herodotus' Histories as a collector's book.

- In Arthur Conan Doyle 's Sherlock Holmes stories, Holmes has numerous collections, which he occasionally uses in his research. For example, in "The Adventure of the Veiled Lodger" he examines newspaper articles from an old murder in a collector's book.

Web links

- Commonplace Books, Harvard Open Collections - digitized commonplace books

- First Line Index of English Verses - includes many lines from commonplace books

- The Poetry of Sight: An Online Commonplace Book

- Richard Katzenv's Marks in the Margin: Reflections on Notable ideas from my Commonplace Book

- Cameron Louis, ed. (1980). The Commonplace Book of Robert Reynes of Acle

- Commonplaces as figures of speech

- Extraordinary Commonplaces , New York Review of Books

- Schools in Tudor England , ISBN 0-918016-28-2

- Commonplace Books by Prof. Lucia Knoles, Assumption College.

- The Zibaldone da Canal commonplace book

- In the Country of Books: Commonplace Books and Other Readings By Richard Katzenv

- Notes About Notes: Commonplace Book

- A Common-place Book of John Milton, and a Latin Essay and Latin Verses Presumed to be by Milton from the Internet Archive

- A new method of making common-place-books, by John Locke from the Internet Archive

Individual evidence

- ↑ Nicholas A. Basbanes , "Every Book Its Reader: The Power of the Printed Word to Stir the World" , Harper Perennial, 2006, p. 82.

- ↑ Christian Works: Elizabeth Lyttelton's commonplace book; English, French, and Latin; 1670s-1713. .

- ↑ Mrs (Anna) Jameson: A commonplace book of thoughts, memories, and fancies; original and selected , Robarts - University of Toronto, London Longman, Brown, Green and Longmans, 1855.

- ^ MD Eddy: Tools for Reordering: Commonplacing and the Space of Words in Linnaeus's Philosophia Botanica . In: Intellectual History Review . 20, 2010, pp. 227-252. doi : 10.1080 / 17496971003783773 .

- ^ Turning the Pages ™ - British Library .

- ^ Armando Petrucci, Writers and Readers in Medieval Italy , trans. Charles M. Radding (New Haven: Yale UP: 1995), 185.

- ^ Dale V. Kent, Cosimo de 'Medici and the Florentine Renaissance: The Patron's Oeuvre (New Haven and London: Yale UP, 2000), p. 69

- ^ Petrucci, 187.

- ↑ An example is the Zibaldone da Canal merchant's manual held at the Kniecke Library, which dates from 1312 and contains hand-drawn diagrams of Venetian ships and descriptions of Venice's merchant culture.

- ↑ Kent, pg. 81.

- ^ Victoria Burke: Recent Studies in Commonplace Books. . In: English Literary Renaissance . 43, No. 1, 2013, p. 154. doi : 10.1111 / 1475-6757.12005 .

- ^ "The Glass Box And The Commonplace Book"

- ^ MD Eddy: He Science and Rhetoric of Paley's Natural Theology . In: Literature and Theology . 18, 2004, pp. 1-22.

- ↑ Adelaide Horatio Seymour Spencer: Adelaide Horatio Seymour Spencer commonplace book, .

- ↑ Woolf in the World: A Pen and a Press of Her Own: Case 4c | Smith College Libraries .