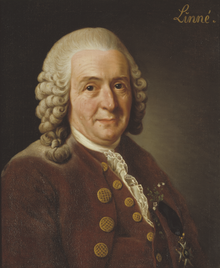

Carl von Linné

Carl von Linné (Latinized Carolus Linnaeus ; before being raised to the nobility in 1756, Carl Nilsson Linnæus ; * May 23, 1707 in Råshult near Älmhult ; † January 10, 1778 in Uppsala ) was a Swedish naturalist who used binary nomenclature to lay the foundations of modern botanical and zoological taxonomy . Its official botanical author abbreviation is " L. ". In zoology “ Linnaeus ”, “ Linné ” and “ Linnæus ” are used as author names.

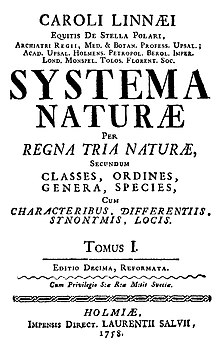

As a student, Linnaeus dealt with the still new idea of the sexuality of plants in his manuscript Praeludia Sponsaliorum Plantarum and with these considerations laid the foundation for his later work. During his stay in Holland, he developed the theoretical foundations of his work in writings such as Systema Naturae , Fundamenta Botanica , Critica Botanica and Genera Plantarum . While working for George Clifford in Hartekamp , Linné was able to study many rare plants directly for the first time and, with Hortus Cliffortianus, created the first plant directory based on his principles. After returning from abroad, Linnaeus worked for a short time as a doctor in Stockholm . He was one of the founders of the Swedish Academy of Sciences and was its first president. Several expeditions took him through the provinces of his Swedish homeland and contributed to his recognition.

At the end of 1741 Linné became professor at Uppsala University and nine years later its rector. In Uppsala , he continued his encyclopedic efforts to describe and classify all known minerals , plants and animals . His two works Species Plantarum (1753) and Systema Naturæ (in the tenth edition of 1758) established the scientific nomenclature used to this day in botany and zoology.

Life

Childhood and school

Carl Linnæus was born on May 23, 1707 in the first hour after midnight in the small town of Råshult in the parish of Stenbrohult in the southern Swedish province of Småland . He was the eldest of five children of cleric Nils Ingemarsson Linnæus and his wife Christina Brodersonia.

His father was very interested in plants and cultivated some unusual plants from Germany in his garden. This fascination carried over to his son, who used every opportunity to go forays into the area and to ask his father to give him the names of the plants. His school education began at the age of seven with a private teacher who taught him for two years. In 1716 his parents sent him to the newly built cathedral school in Växjö with the aim that he would later become a pastor like his father and grandfather. The young Linnaeus suffered from the rigid educational methods of the school. That only changed when he made the acquaintance of the student Gabriel Höök in 1719, who taught him privately. In 1724 he switched to high school.

In 1726 his father traveled to Växjö to consult the doctor Johan Stensson Rothman on a medical matter and to find out about his son's achievements. He had to learn that his son was only mediocre in the subjects of Greek , Hebrew , theology , metaphysics and rhetoric, which are necessary for the pastoral office , and showed little interest in them. In contrast, his son excelled in mathematics and the natural sciences , but also in Latin . Rothman, recognizing Linnaeus' talent for a medical career, offered the shocked father to take his son into his home free of charge and teach him botany and physiology . Rothman introduced Linnaeus to the classification system of plants by Joseph Pitton de Tournefort and referred him to Sébastien Vaillant's writing on the sexuality of plants.

Education

In August 1727 Linnaeus went to Lund to study at the university there. At the end of his school years he had received a not very flattering letter from the principal of the grammar school Nils Krok for his application in Lund. His old friend Gabriel Höök, meanwhile master of philosophy in Lund, advised him not to use writing. He presented the rector of the University of Lund Linnaeus instead as his private students before and so reached the enrollment at the University of Lund. Höök convinced Professor Kilian Stobæus to take Linné into his home. In addition to an extensive collection of natural objects, Stobæus had a very extensive library, which Linnaeus was not allowed to use. However, through the German student David Samuel Koulas, who was temporarily employed as the secretary of Stobæus, he was given access to the books that he studied until late at night. In return, he gave Koulas the knowledge he had learned in physiology from Rothman . Amazed by the nightly activities of his pupil, Stobæus suddenly stepped into Linnaeus' room one night and, to his surprise, found him absorbed in studying the works of Andrea Cesalpino , Caspar Bauhin and Joseph Pitton de Tournefort . From then on, Linnaeus had free access to the library.

During his stay in Lund, Linné regularly went on excursions in the area. This was also the case on a warm day at the end of May 1728, when he and his fellow student Mattias Benzelstierna explored the nature in Fågelsång and was bitten by a small, inconspicuous animal, the " Hell Fury ". The wound became infected and could only be treated with difficulty. Linnaeus narrowly escaped death. Linnaeus went to his home country to relax in the summer. Here he met his teacher Rothman again, to whom he reported on his experiences at Lund University. Through this report, Rothman, who had studied at Uppsala University , came to the conclusion that Linnaeus had better pursue his medical studies in Uppsala. Linnaeus followed this advice and set out for Uppsala on September 3, 1728.

The conditions that Linnaeus found at the university there were desolate. Olof Rudbeck the Younger gave a few lectures on birds and Lars Roberg philosophized on Aristotle . There were no lectures on medicine and chemistry , no autopsies were carried out, and barely two hundred species grew in the old botanical garden . In March 1729 Linné made the acquaintance of Peter Artedi , with whom he was a close friend until his untimely death. Artedi's main interest was chemistry, but he was also a botanist and zoologist. The two friends tried to outdo each other with their research. They soon realized that it would be better if they divided up the various areas of the three natural kingdoms according to their interests. Artedi took over the amphibians, reptiles and fish, Linnaeus the birds and insects and, with the exception of the umbelliferae , the entire botany. Together they worked on the mammals and the minerals .

Around this time, Olof Celsius the elder took him into his house. Linné helped Celsius finish his Hierobotanicon work . Linnaeus' financial situation improved. In June 1729 he received a royal scholarship (2nd class), which was increased again in December 1729 (1st class). At the end of 1729 his first important work, Praeludia Sponsaliorum Plantarum , was written, in which he dealt with the sexuality of plants for the first time and paved the way for his further life's work. The script quickly became known and Olof Rudbeck sought out Linnaeus' personal acquaintance. First he got Linné, against Roberg's resistance, the position of demonstrator of the botanical garden and hired him to teach his three youngest sons. In mid-June Linnaeus moved into Rudbeck's house.

In 1730/31 Linné worked on a catalog of the plants of the Uppsala Botanical Garden ( Hortus Uplandicus , later title Adonis Uplandicus ), of which several versions were created. In the beginning, the plants were arranged according to the Tournefort system for the classification of plants, but Linnaeus had more and more doubts about its validity. In the final version of July 1731, which he completed in Stockholm, he arranged the plants according to his own system consisting of 24 classes. It was during this time that the first drafts of his early works emerged and were published in Amsterdam. At the end of 1731, Linnaeus felt compelled to leave Rudbeck's house because the wife of the university librarian Andreas Norrelius (1679–1750), who also lived there at the time, spread rumors about him that undermined the good relationship with Rudbeck's family. He spent the turn of the year with his parents.

Journey through Lapland

In a letter dated December 26, 1731, Linnaeus recommended himself to the Royal Society of Sciences in Uppsala for an expedition to the largely unexplored Lapland and asked for the necessary financial support. When he received no answer, he made another attempt at the end of April 1732 and reduced the amount of money required for the trip by a third. This time the amount was granted to him and he began his first major expedition on May 23rd.

The arduous journey, during which he recorded all his experiences and discoveries in a diary, lasted almost five months. He returned to Uppsala on October 21, 1732. In addition to the hardships of the trip and the debts that Linnaeus had taken on, there was also the disappointment that the academy only published a few pages of its results. His book on the Lappish flora, Flora Lapponica , was not published until 1737 in Amsterdam.

From this trip he brought with him the rules and board of the game Tablut, which was widespread in the Viking Age .

Falun and the journey through Dalarna

In the spring semester of 1733, Linnaeus held private courses in docimastics and wrote a short treatise on a topic that was new to him. He cataloged his bird and insect collection and worked on numerous manuscripts. From Clas Sohlberg, one of his students, he received an invitation to spend the turn of the year 1733/1734 with his family in Falun . Clas' father, Eric Nilsson Sohlberg, was the inspector of the mines there, and so Linnaeus had the opportunity to study the mines extensively. He did not return to Uppsala until March 1734 and continued to give private lessons in mineralogy, botany and dietetics .

During her stay in Falun, Linnaeus made the acquaintance of Johan Browall , who was teaching the children of the Governor of Dalarna Province , Nils Reutersholm. Reutersholm was impressed by the reports on Linnaeus' trip to Lapland and planned to conduct such an exploration tour in the province he administered. Sufficient donors were found for the company, and the eight-member Societas Itineraria Reuterholmiana (Reuterholm Travel Society), of which Linné was president, was founded. The journey through the province of Dalarna began on July 3, 1734 and lasted until August 18, 1734. Linné's travelogue Iter Dalecarlicum was only published posthumously.

Linnaeus stayed in Falun and took over the lessons from Reutersholm's sons. Browall convinced him to go abroad to receive his doctorate, which he had previously been unable to do due to his tight financial situation. A solution for the travel expenses was finally found. Linnaeus was supposed to accompany and teach Clas Sohlberg to Holland and do his doctorate there. He returned to Uppsala to make his travel arrangements, and after a brief stay in Stockholm, he returned to Falun at the end of the year. At the turn of the year 1734/35 he met Sara Elisabeth Moraea, a daughter of the city doctor in Falun, and proposed marriage to her. This was accepted by her father, who was concerned about the economic independence of his daughter, on the condition that Linnaeus obtain his doctorate and the wedding would take place within the next three years.

Three years in Holland

Linné's journey south took him via Växjö and Stenbrohult. On April 15, 1735, he left Stenbrohult for Germany. At the beginning of May he reached Travemünde and immediately went to Lübeck , from where he traveled by stagecoach to Hamburg the next morning . Here he met Johann Peter Kohl , the editor of the journal Hamburgische Reports von Neue Gelehrten Dinge . He visited the extensive garden of lawyers Johann Heinrich von Spreckelsen , where he, among others, 45 aloe and 56 mesembs counted Species. He also paid a visit to the library of Johann Albert Fabricius . As Linnaeus imprudently a seven-headed hydra that stood at a high price for sale and the brother of Hamburg's mayor Johann Anderson belonged, as fake unmasked, told him the doctor Gottfried Jacob Jänisch to leave Hamburg quickly, to go to possible trouble out of the way . Linnaeus left Altona for Holland on May 27th .

Linné arrived in Amsterdam on June 13th . He stayed here for only a few days and sailed to Harderwijk on the evening of June 16 to finally receive the long-awaited degree as a doctor of medicine. On the same day he wrote in the album studiosorum the University of Harderwijk one. Two days later he passed his exam as Candidatus Medicinae with Johannes de Gorter and handed him his dissertation Hypothesis Nova de Febrium Intermittentium Causa , which he had already completed in Sweden. He spent the remaining days before his exam, botanizing with David de Gorter, the son of his examiner. On Wednesday, June 23, 1735, he passed his exam and returned to Amsterdam the next day after he was given his diploma. He stayed here only for a short time, because he really wanted to get to know Herman Boerhaave , who worked in Leiden . The meeting at Boerhaave's country estate Oud Poelgeest only came about thanks to the support of Jan Frederik Gronovius , who issued him a letter of recommendation . Previously, Linnaeus Gronovius and Isaac Lawson had shown some of his manuscripts , including a first draft of Systema Naturae . Both were so impressed by the originality of Linné's approach to classifying the three natural kingdoms - minerals , plants, and animals - that they decided to publish the work at their own expense. Gronovius and Lawson worked as proofreaders for this and other works by Linnaeus, which were written in Holland, and monitored the progress of the printing process .

On Boerhaave's recommendation, Linnaeus found work and accommodation with Johannes Burman , whom he helped put together his Thesaurus Zeylanicus . Linné completed his Bibliotheca Botanica in Burman's house and met the banker George Clifford there on the recommendation of Gronovius . Gronovius had suggested to Clifford to hire Linnaeus as curator of his collection in Hartekamp and let him describe his garden, the Hortus Hartecampensis . On September 24, 1735, Linné began working in Hartekamp. Only five days later he received the message that his friend Peter Artedi , whom he had just met by chance in Amsterdam a few weeks earlier, had drowned in an Amsterdam canal . Linnaeus fulfilled the mutual promise of the friends to continue and publish the work of the other and edited and published the works of Artedi during his time in Holland.

Soon after Linnaeus' arrival in Hartekamp, the German plant draftsman Georg Dionysius Ehret arrived there, who was hired as a draftsman by Clifford for a while. Linné explained his new classification system for plants to him, whereupon Ehret made a drawing with the distinguishing features of the 24 classes, initially for his private use. The panel, entitled Caroli Linnaei classes sive literae , was occasionally bound together with the first edition of Linné's Systema Naturae and was part of several other of his works. In Hartekamp, Linné worked on several projects at the same time. This is how he created his works Fundamenta Botanica , Flora Lapponica , Genera Plantarum and Critica Botanica and went to the printer page by page after correction . At the same time, with the help of the German gardener Dietrich Nietzel, he succeeded in bringing the banana plant growing in one of Clifford's warm houses to bloom and set fruit. This event prompted him to write the essay Musa Cliffortiana . The work is the first monograph on a plant genus .

England and France

In the summer of 1736, Linné's work in Holland was interrupted by a trip to England . In London he studied Hans Sloane's collection and received rare plants for Clifford's garden from Philip Miller at the Chelsea Physic Garden . During the month-long stay, he met Peter Collinson and John Martyn . During a short stay in Oxford he met Johann Jacob Dillen . Back in Hartekamp, Linnaeus continued to work on the Hortus Cliffortianus under increasing pressure from Clifford , the completion of which was delayed until 1738 due to problems with the engravings .

In the summer of 1737, Boerhaave offered him the post of doctor for the WIC, the Dutch West India Company in Dutch Guiana . He refused, however, and instead recommended the doctor Johann Bartsch to Boerhaave , who had helped him with the processing of his Flora Lapponica . At this time Linnaeus already had plans to leave Holland and turned down all offers from Clifford to stay at his expense. Only when Adriaan van Royen asked him to rearrange the botanical garden in Leiden according to his system and at least stay there for the winter, did Linnaeus give in. His travel plans, however, were fixed. Via France and Germany , where he hoped to meet Albrecht von Haller in Göttingen, among others , he wanted to return to Sweden for good. A severe fever from which he suffered for several weeks at the beginning of 1738 delayed his departure further and further.

In May 1738, Linnaeus had recovered enough to be able to travel to France. From Leiden he traveled to Paris via Antwerp , Brussels , Mons , Valenciennes and Cambrai . Van Royen had given him a letter of recommendation to Antoine de Jussieu . Due to lack of time, he entrusted him to the care of his brother Bernard de Jussieu , who at that time held the chair of botany at the Jardin du Roi . Together they visited the Royal Garden, the herbaria of Joseph Pitton de Tournefort , Sébastien Vaillant and Joseph Donat Surian as well as the book collection of Antoine-Tristan Danty d'Isnard and went on botanical excursions in the Paris area.

During a meeting of the Paris Academy of Sciences , Linnaeus became a corresponding member of the Academy on the basis of a suggestion by Bernard de Jussieu. The superintendent of the Jardin du Roi Charles du Fay tried in vain to convince Linnaeus to stay in France. Linnaeus finally wanted to return to his homeland. He gave up the plan to travel to Germany and, after a month's stay in France in Rouen , embarked for Sweden.

Return to Sweden and marriage

Linnaeus arrived in Helsingborg via the Kattegat . After a short stay with his family in Stenbrohult, he traveled on to Falun, where shortly afterwards the engagement to Sara Elisabeth Moraea took place. In order to earn a living, he settled in Stockholm as a doctor in September 1738 . After initial difficulties, he quickly gained access to Stockholm society through his acquaintance with Carl Gustaf Tessin . Together with Mårten Triewald , Anders Johan von Höpken , Sten Carl Bielke , Carl Wilhelm Cederhielm and Jonas Alströmer , he founded the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences in May 1739 and became its first president. According to the statutes, he gave up the presidency at the end of September 1739.

Also in May 1739 he succeeded Triewald at the Royal Mining College in Stockholm, where he lectured on botany and mineralogy, and on a recommendation from Admiral Theodor Ankarcrona, doctor of the Swedish Admiralty.

With such financial security he was able to marry his fiancée Sara Elisabeth Moraea on June 26, 1739. The marriage resulted in seven children: Carl, Elisabeth Christina , Sara Magdalena, Lovisa, Sara Christina, Johannes and Sofia. Sara Magdalena and Johannes died in childhood. Linnaeus' son Carl , like his father, became a botanist, but was only able to continue his father's work for a short time and died at the age of 42.

Journey through Öland and Gotland

A month after his wedding, Linnaeus returned to Stockholm. In January 1741 he received an offer from the Estates' Congress to explore the islands of Öland and Gotland . Linnaeus and his six companions, including Johan Moraeus, a brother of his wife, left Stockholm on May 26, 1741. They were on the road for two and a half months and, through their activities in the run-up to the Russo-Swedish War, sometimes aroused suspicion of Russian espionage activities. With the publication of the travelogue Ölandska och Gothländska Resa in 1745, Linné had written for the first time a work in his Swedish mother tongue. The index of the work, in which the plants were abbreviated in two parts, is remarkable . In addition, a numerical index was used to refer to the species in the Flora Suecica work published in the same year .

Professor in Uppsala

Olof Rudbeck died in the spring of 1740 , and his professorship for botany at Uppsala University had to be filled. Lars Roberg , holder of the chair for medicine, wanted to retire soon, so this chair was also to be reassigned. In addition to Linné, there were two other contenders, Nils Rosén von Rosenstein and Johan Gottschalk Wallerius . In consultation with the Swedish Chancellor Carl Gyllenborg , Rosén should be given the position of Rudbeck and Linné the vacant position of Roberg. Later they were supposed to swap chairs. Linné's official appointment as professor of medicine took place on May 16, 1741. In his "speech on the importance of traveling in one's own country" on the occasion of taking over the chair, which he held on November 8, 1741, he emphasized the economic benefits, which would result from a mapping of the Swedish nature. However, it is not only important to study nature, but also local diseases, their healing methods and the various agricultural methods. His first public lecture took place less than a week later.

At the end of the year, Linnaeus and Rosén exchanged chairs. Linnaeus taught botany, dietetics , materia medica and was in charge of the old botanical garden . Rosén taught practical medicine, anatomy and physiology . They were jointly responsible for the fields of pathology and chemistry. Linnaeus began to redesign the botanical garden and commissioned Carl Hårleman to do it . Olof Rudbeck the Elder's house belonging to the garden was renovated and Linnaeus moved in with his family. New greenhouses were built in the garden and plants from all over the world settled. In his work Hortus Upsaliensis in 1748, Linnaeus described around 3000 different plant species that were cultivated in this garden. In his Materia Medica , a manual for doctors and pharmacists published in 1749, he described medicinal plants and their practical use. In 1750 he became rector of Uppsala University. He held this position until a few years before his death.

Before taking office as rector, Linnaeus had made two more trips to Sweden. From June 23 to August 22, 1746 he toured the province of Västergötland together with Erik Gustaf Lidbeck , who later became a professor in Lund . Linné's notes appeared a year later under the title Västgöta Resa . One last trip took Linné from May 10 to August 24, 1749 through the southernmost Swedish province of Skåne . His student Olof Andersson Söderberg , who had completed his doctorate with him the previous year and was later a professor in Halle, assisted him as his secretary during the trip. The Skånska Resa was published in 1751. In mid-December 1772 he gave his farewell speech on “The joys of nature”.

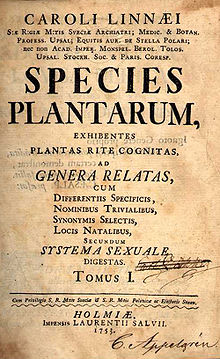

Species Plantarum

Linné's travels through Sweden made it possible for him to describe the flora and fauna of Sweden in detail in the works Flora Suecica (1745) and Fauna Suecica (1746). They were important steps towards the completion of his two most important works Species Plantarum (first edition 1753) and Systema Naturae (tenth edition 1759). Linnaeus encouraged his students to explore the nature of unexplored regions for themselves, and also gave them the opportunity to do so. He called the students who went on a voyage of discovery " his apostles ".

In 1744 the Danish pharmacist August Günther sent him five volumes of the herbarium, which Paul Hermann had made in Ceylon from 1672 to 1677 , and asked Linnaeus to help him identify the plants. Linnaeus was able to use around 400 of the approximately 660 herbarized plants and place them in his classification system. He published his results in 1747 as Flora Zeylanica .

A severe attack of gout forced Linnaeus in 1750 to dictate the content of Philosophia Botanica (1751) to his pupil Pehr Löfling . The work based on his 365 aphorisms formulated in Fundamenta Botanica was conceived as a textbook on botany. In it he presented his system for differentiating and naming plants and explained it with brief comments. From the middle of 1751 to 1752 Linné worked intensively on the completion of Species Plantarum . In the two volumes published in mid-1753, he described all the plants on earth known to him on 1200 pages with around 7300 species. The epithet , which he noted as a marginal note for each type in the margin and which was an innovation compared to his earlier works, is of particular importance . The generic name and the epithet together form the two-part name of the species, as it is still used today in modern botanical nomenclature .

Systema Naturae

In the year Species Plantarum was published, Museum Tessinianum was a list of the objects in the mineral and fossil collection of Carl Gustaf Tessin , which Linnaeus had made. Collecting natural historical curiosities was also very common in Sweden at the time. Adolf Friedrich had brought together a collection of rare animal species in Drottningholm Palace and commissioned Linnaeus to take an inventory. Linnaeus spent a total of nine weeks at the king's castle between 1751 and 1754. The first volume of Museum Adolphi Friderici (1754) contained 33 drawings (two of monkeys , nine of fish and 22 of snakes ). It is the first work in which binary nomenclature was used consistently in zoology.

In the 10th edition of Systema Naturae , Linné finally adopted the binary nomenclature for the animal species described in the first volume. In the second volume of Systema Naturae he dealt with plants. An originally planned third volume, which should have the content of the minerals, did not appear. 1758, the year Systema Naturae was published , marks the beginning of modern zoological nomenclature .

The Swedish Queen Luise Ulrike had also set up a natural history collection in her Ulriksdal Castle , which consisted of 436 insects , 399 mussels and 25 other molluscs and was described in the treatise Museum Ludovicae Ulricae (1764) by Linnaeus. The appendix was the second volume of the description of her husband's museum with 156 animal species.

Last years

In the last years of his life, Linnaeus was busy editing the twelfth edition of Systema Naturae (1766–1768). The works Mantissa Plantarum (1767) and Mantissa Plantarum Altera (1771) were created as appendices . In them he described new plants that he had received from his correspondents around the world.

In May 1774 he suffered a stroke during a lecture in the Botanical Garden at Uppsala University . A second stroke in 1776 paralyzed his right side and restricted his mental abilities. Carl von Linné died on January 10, 1778 of a bladder ulcer and was buried in Uppsala Cathedral.

Reception and aftermath

The British botanist William Thomas Stearn , who worked in the 20th century , summarized Linnaeus' importance as follows:

“Although Linnaeus has been described as a pioneering ecologist, geobotanist, dendrochronologist, evolutionist, botanical pornographer, sexualist, and more, his most influential and valuable contributions to biology are undoubtedly the successful introduction of binary nomenclature for plant and animal species, if only that achievement was a coincidental by-product of his enormous encyclopedic activity in order to provide the means for recognizing and recording their genera and species in a concise, precise and practical form. "

Life's work

With his directories Species Plantarum (for plants, 1753) and Systema Naturae (for plants, animals and minerals, 1758/1759 and 1766–1768, respectively) Linnaeus created the basis of modern botanical and zoological nomenclature . In these two works he also gave an epithet for each species described . Together with the name of the genus , it served as an abbreviation of the actual species name, which consisted of a long descriptive word group (phrase). From Canna foliis ovatis utrinque acuminatis nervosis , the easy-to-remember name Canna indica emerged . The result of the introduction of two-part names is the consistent separation of the description of a species from its designation. This separation made it possible to incorporate newly discovered plant species into its system without any problems. Linné's system included the three natural kingdoms minerals (including fossils), plants and animals. In contrast to his contributions to botany and zoology, whose fundamental importance for biological systematics was quickly recognized, his mineralogical investigations remained meaningless because he lacked the necessary chemical knowledge. The first chemically based classification of minerals was established in 1758 by Axel Frederic von Cronstedt .

The contemporary natural scientist Georges-Louis Leclerc de Buffon was in fundamental opposition to Linné's view that all of nature can be captured in a taxonomy . Buffon believed that nature was too diverse and too rich to conform to such a strict framework. The philosopher Michel Foucault described Linnaeus' approach to classification in such a way that it was a matter of "systematically seeing few things". It was particularly important to him to resolve the similarities of things in the world. Linnaeus wrote in his Philosophia Botanica : "All dark similarities have only been introduced to the disgrace of art". Linné also assumed the constancy of species : "There are as many species as God created different shapes in the beginning." He deliberately divided the species into classes and orders based on artificially selected characteristics such as number, shape, size and location , to create an easy to use and easy to learn system for the classification of the species. In the case of plants, for example, he used characteristics of the stamens to determine the class and characteristics of the pistils to determine the order of a plant species. In this way a so-called “artificial system” was created, as it did not take into account the natural relationships between the species. He considered the genera and species to be natural and therefore classified them according to their similarity using a variety of characteristics. Linnaeus endeavored to create a "natural system", but did not get beyond approaches such as Ordines Naturales in the sixth edition of Genera Plantarum (1764). It was only Antoine-Laurent de Jussieu who succeeded in establishing such a natural system for plants.

Awards and recognition

On January 30, 1747, Linnaeus was appointed archiater (personal physician) to the king. On April 27, 1753 he was awarded the North Star Order . At the end of 1756 Carl Linnaeus was ennobled by the Swedish King Adolf Friedrich and was given the name Carl von Linné. The nobility letter , dated April 20, 1757, was signed by the king in November 1761. The elevation to the nobility did not take effect until the end of 1762 when it was confirmed by the Riddarhuset .

Linnaeus was a member of numerous scientific academies and learned societies . These included the German Academy of Sciences Leopoldina , to which he belonged from October 3, 1736 ( matriculation number 464 ) under the academic surname Dioscorides II , the Royal Society of Sciences in Uppsala , the Société Royale des Sciences de Montpellier , the Royal Prussian Academy of Sciences , the Royal Society , the Académie royale des Sciences, Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres de Toulouse, the Paris Academy of Sciences , the Russian Academy of Sciences in Saint Petersburg and the Royal Great Britain Churfürstliche Braunschweigische Lüneburgische Landwirthschaftsgesellschaft Celle .

Jan Frederik Gronovius named the genus Linnaea (moss bells) of the Linnaeaceae plant family in honor of Linnaeus . The lunar crater Linnaeus in Mare Serenitatis , the asteroid Linnaeus and the mineral Linneit are named after him. He is also the namesake for the Linnaeus Terrace in the Antarctic.

In 1959, the botanist William Thomas Stearn proposed the skeleton of Carl von Linné, buried in Uppsala Cathedral, as a lectotype for the species Homo sapiens . Homo sapiens was thus validly defined according to the zoological nomenclature rules as the animal species to which Carl von Linné belonged.

The 100 kroner banknote of the Swedish krona bore the portrait of Carl von Linné from 2001 to June 30, 2017.

Estate and correspondence

After the death of Linnaeus and the death of his son Carl , his wife Sara offered the entire estate of Joseph Banks for 3,000 guineas . However, this refused and convinced James Edward Smith to purchase the collection. In October 1784, Linné's collection arrived in London and was on public display in Chelsea . Today Linnaeus' estate is owned by the London Linnaeus Society , whose highest honor is the Linnaeus Medal , which is awarded annually .

Up until his death, Linnaeus maintained an extensive correspondence with partners all over the world. Of these, around 200 came from Sweden and 400 from other countries. Over 5000 letters have been preserved. His correspondence with Abraham Bäck alone , his close friend and confidante, comprises well over 500 letters.

Important botanical and zoological correspondents were Herman Boerhaave , Johannes Burman , Jan Frederik Gronovius and Adriaan van Royen in Holland, Joseph Banks , Mark Catesby , Peter Collinson , Philip Miller , James Petiver and Hans Sloane in England, Johann Reinhold Forster , Johann Gottlieb Gleditsch , Johann Georg Gmelin and Albrecht von Haller in Germany, Nikolaus Joseph von Jacquin in Austria, and Antoine Nicolas Duchesne and Bernard de Jussieu in France.

critic

The drawing is by Jan Wandelaar .

The analogy of plants and animals with regard to their sexuality, used by Linné as a student in Praeludia Sponsaliorum Plantarum as early as 1729, provoked many of his contemporaries to criticism.

Johann Georg Siegesbeck wrote the first criticism of Linné's sexual system of plants in 1737 in an appendix to his book Botanosophiae : “[If] eight, nine, ten, twelve or even twenty or more men are found in the same bed with a woman [or if] where the beds of the real married form a circle, the beds of the prostitutes also form a circle, so that married men are mated [...] Who would believe that God established such abhorrent fornication in the kingdom of plants? Who could expose such an unchaste system to the academic youth without causing offense? "

In L'Homme Plante (1748, shortly thereafter part of L'Homme Machine ) Julien Offray de La Mettrie mocked Linnaeus' system by classifying humanity using the terms introduced by Linnaeus. He referred to humanity as Dioecia (i.e. male and female flowers on different plants). Males belong to the order Monandria (a stamen ) and women to the order Monogyna (a pistil ). He interpreted the sepals as clothing, the petals as limbs, the nectaries as breasts, and so on.

Even Johann Wolfgang von Goethe , who admitted that “after Shakespeare and Spinoza, the greatest effect on me came from Linnaeus, precisely through the conflict to which he asked me to”, judged: “If innocent souls, to get through They cannot hide the fact that they have offended their moral feelings to advance their own studies, to pick up botanical textbooks; the eternal weddings, which one cannot get rid of, whereby the monogamy, on which custom, law and religion are based, completely dissolves into vague lust, remains unbearable to the pure human sense. "

In 2016, a commission of the city of Freiburg im Breisgau , chaired by Bernd Martin and including Nina Degele , advised an additional sign under the street sign on Carl-von-Linné-Straße with the wording: "Swedish natural scientist and founder of biological systematics, Thought leaders of a biologically based gender hierarchy and race theory ”. Ulrich Kutschera criticizes the commission; she discredits “a great biologist”, and many of her statements are also “factually incorrect”. Axel Meyer named Linné an important founder of modern biology who was defamed by the Freiburg shield. The people in charge in Freiburg seemed to him as if they wanted to reprogram the evolutionary legacy of human beings by means of gendered Newspeak about a scientific genius. Such attempts show him the whole hubris of gender studies , which do not describe people or understand them better, but want to re-educate them ideologically.

Fonts

Works (selection)

Linnaeus has authored numerous books, many of which have appeared in multiple editions. Some of them are available in digitized form from various providers such as the Gallica project of the French National Library , the Online Library of Biological Books , the Göttingen State and University Library , the Botanicus Digital Library and the Google Book Search in full text. The most important works of Linnaeus include:

- Praeludia Sponsaliorum Plantarum . Uppsala, 1729

- Florula Lapponica . In Acta Literaria et Scientiarum Sueciae . Volume 3, pp. 46-58, 1732

- Systema Naturae . Johan Wilhelm de Groot, Leiden 1735

- Bibliotheca Botanica . Salomon Schouten, Amsterdam 1735; digitized version , full text

- Fundamenta Botanica . Salomon Schouten, Amsterdam 1735; digitized version

- Musa Cliffortiana . Leiden 1736; digitized version

- Flora Lapponica . Salomon Schouten, Amsterdam 1737; digitized version

- Genera Plantarum . Conrad Wishoff, Leiden 1737; digitized version of the 2nd edition

- Critica Botanica . Conrad Wishoff, Leiden 1737; digitized versions: Google books , ULB Düsseldorf

- Hortus Cliffortianus , Amsterdam 1738; digitized version

- Classes Plantarum . Conrad Wishoff, Leiden 1738; digitized versions: Gallica , ULB Düsseldorf

- Öländska och Gothländska Resa . Gottfried Kiesewetter: Stockholm and Uppsala 1745; digitized version

- Flora Suecica . Lars Salvius: Stockholm 1745; digitized version

- Fauna Suecica . Lars Salvius: Stockholm 1746; digitized version

- Västgöta Resa . Lars Salvius: Stockholm 1747; digitized version

- Flora Zeylanica . Lars Salvius: Stockholm 1747; digitized versions: Stueber , Bayerische Staatsbibliothek

- Hortus Upsaliensis . Lars Salvius: Stockholm 1748; digitized version

- Materia Medica . Lars Salvius: Stockholm 1749; digitized version

- Skånska Resa . Lars Salvius: Stockholm 1751; digitized version

- Philosophia Botanica . Gottfried Kiesewetter: Stockholm 1751; digitized version

- Species Plantarum . Lars Salvius: Stockholm 1753; digitized version

- Museum Tessinianum . Lars Salvius: Stockholm 1753; digitized version

- SRM Adolphi Friderici Museum . Lars Salvius: Stockholm 1754

- Systema Naturae . 10th edition, Lars Salvius: Stockholm 1758; digitized version

- Museum SRM Ludovicae Ulricae . Lars Salvius: Stockholm 1764; digitized version

- Mantissa plantarum . Lars Salvius: Stockholm 1767; digitized versions: Google Books , Bayerische Staatsbibliothek

- Mantissa Plantarum Altera . Lars Salvius: Stockholm 1771; digitized versions: Gallica , Bayerische Staatsbibliothek

Magazine articles

Linné has written articles for the following magazines:

- Acta Societatis Regiae Scientiarum Upsaliensis

- Kongliga Svenska Vetenskaps Academiens Handlingar

- Memoires de l'Academie Royale des Sciences de Paris

- Nova Acta Regiae Societatis Scientiarum Upsaliensis

- Novi Commentarii Academiae Scientiarum Imperialis Petropolitanae

- Post and Inrikes Tidningar

Dissertations

Under the chairmanship of Linné, a total of 185 dissertations were written between 1743 and 1776 , which are often directly attributed to him. The dissertations of his doctoral students were published in the ten-volume Amoenitates Academicae (Stockholm or Erlangen, 1751–1790).

literature

Biographies

- Wilfrid Blunt : The Compleat Naturalist: A Life of Linnaeus . 2001. ISBN 0-7112-1841-2

- Cecilia Lucy Brightwell: A life of Linnaeus . London 1858

- Florence Caddy: Through the fields with Linnaeus . 2 volumes, London 1887

- Theodor Magnus Fries : Linné: Lefnadsteckning . 2 volumes, Stockholm, 1903

- Heinz Goerke: Linnaeus. Doctor - naturalist - systematist . Stuttgart 1966

- Edward Lee Greene: Carolus Linnaeus . Philadelphia 1912

- Benjamin D. Jackson: Linnaeus . London 1923

- Lisbet Koerner: Linnaeus: Nature and Nation . Harvard University Press 1999. ISBN 0-674-00565-1

- Richard Pulteney : A General View of the Writings of Linnaeus . London 1781

- Dietrich Heinrich Stöver: Life of the knight Carl von Linné , Verlag Hoffman, Hamburg 1792. English edition: The Life of Sir Charles Linnaeus London 1794

Bibliographies of his writings

- Basil Harrington Soulsby: A catalog of the works of Linnaeus (and publications more immediately.) Preserved in the libraries of the British Museum (Bloomsbury) and Museum (Natural History - Kensington) . 2nd edition, London 1933

- Johan Markus Hulth: Bibliographia linnaeana. Materiaux pour servir a une bibliographie linnéenne . Uppsala 1907

- Felice Bryk: Bibliographia Linnaeana ad Species plantarum pertinens . In: Taxon . Volume 2, No. 3, May 1953, pp. 74-84. doi : 10.2307 / 1217345

- Felice Bryk: Bibliographia Linnaeana ad Genera plantarum pertinens . In: Taxon . Volume 3, No. 6, Sept. 1954, pp. 174-183. doi : 10.2307 / 1215955

Correspondence

- Theodor Magnus Fries, Johan Markus Hulth (editor): Bref och skrifvelser af och till Carl von Linné . 8 volumes, Stockholm 1907–1922

- James Edward Smith (Editor): A Selection of the Correspondence of Linnaeus . 2 volumes, London 1821

- Correspondence from Carl von Linné

To the reception of his work

- AJ Boerman: Carolus Linnaeus. A Psychological Study . In: Taxon . Volume 2, No. 7, Oct. 1953, pp. 145-156. doi : 10.2307 / 1216487

- Felix Bryk: Promiscuity of the species as a species-forming factor. For the bicentenary of the year of publication of the fifth edition of Linnés Genera plantarum (1754) . In: Taxon . Volume 3, No. 6, Sept. 1954, pp. 165-173. doi : 10.2307 / 1215954

- John Lewis Heller: Linnaeus's Hortus Cliffortianus . In: Taxon . Volume 17, No. 6, Dec. 1968, pp. 663-719. doi : 10.2307 / 1218012

- John Lewis Heller: Linnaeus's Bibliotheca Botanica . In: Taxon . Volume 19, No. 3, June, 1970, pp. 363-411. doi : 10.2307 / 1219065

- James L. Larson: Linnaeus and the Natural Method . In: Isis . Volume 58, No. 3, Fall 1967, pp. 304-320

- James L. Larson: The Species Concept of Linnaeus . In: Isis . Volume 59, No. 3, Herbst, 1968, pp. 291-299

- EG Linsley, RL Usinger: Linnaeus and the Development of the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature . In: Systematic Zoology . Volume 8, No. 1, March, 1959, pp. 39-47. doi : 10.2307 / 2411606

- Karl Mägdefrau : history of botany . Gustav Fischer Verlag : Stuttgart 1992, pp. 61-77. ISBN 3-437-20489-0

- Staffan Müller-Wille, Karen Reeds: A translation of Carl Linnaeus's introduction to Genera plantarum . In: Studies in History and Philosophy of Science, Part C: Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences . Volume 38, No. 3, September 2007, pp. 563-572. doi : 10.1016 / j.shpsc.2007.06.003

- Staffan Müller-Wille: Collection and collation: theory and practice of Linnaean botany . In: Studies in History and Philosophy of Science, Part C: Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences . Volume 38, No. 3, September 2007, pp. 541-562. doi : 10.1016 / j.shpsc.2007.06.010

- Peter Seidensticker: Plant names: Tradition, research problems, studies . Franz Steiner Verlag: 1999. ISBN 3-515-07486-4

- WT Stearn : The Background of Linnaeus's Contributions to the Nomenclature and Methods of Systematic Biology . In: Systematic Zoology . Volume 8, No. 1, March 1959, pp. 4-22. doi : 10.2307 / 2411603

Others

- Diary of the trip through Lapland Iter Lapponicum

- German Lapland trip . Translated from the Swedish by HC Artmann . Insel Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1964

- Diary of the trip through Dalarna Iter Dalekarlicum

- International diary Iter ad exteros

- Carl Linné: The Lord's Archiatrist and Knight von Linné's travels through some Swedish provinces . Curt: Halle 1764 Volume 1 , Westgothland Volume 2

- Nemesis Divina (fully edited in Swedish 1968; in German 1983, by Wolf Lepenies, Lars Gustafsson, Ullstein: Frankfurt / M.)

Web links

- Literature by and about Carl von Linné in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Carl von Linné in the German Digital Library

- Author entry and list of the described plant names for Carl von Linné at the IPNI

- Life data ( memento of August 27, 2006 in the Internet Archive ) of ancestors and descendants

- The Linnaeus Server u. a. with Museum Adolphi Friderici (English)

- Works in the Royal Library of Stockholm a . a. Systema Naturae . 1st edition (Swedish)

- The Linnean Collections

- The Linnaean Plant Name Typification Project

Individual evidence

- ↑ During Linnaeus' life there were several changes in the calendar used in Sweden. The Swedish calendar was in use from March 1700 to February 1712 . After this, his birthday was May 13th, 1707. From March 1712 the Julian calendar was used again. The Gregorian calendar only came into force in Sweden from 1753 . In the article all dates are given according to the Gregorian calendar.

- ^ Sébastien Vaillant: Sermo de Structura Florum . Leiden, 1718

- ^ Letter of May 6, 1727 from Nils Krok to the rector of Lund University

- ^ Carl Linnaeus to Kilian Stobaeus, November 19, 1728, Letter L0001 in The Linnaean correspondence (accessed March 11, 2008).

- ↑ James Edward Smith (editor): Iter Lapponicum . (Lapland trip) 1811.

- ↑ Florula Lapponica . In: Acta Literaria et Scientiarum Sueciae . Volume 3, 1732, pp. 46-58.

- ↑ Carl Linnaeus to Gabriel Gyllengrip, October 5, 1733, letter L0027 in The Linnaean correspondence (accessed March 11, 2008).

- ^ Hypothesis Nova de Febrium Intermittentium Causa

- ^ Johan Frederik Gronovius to Carl Linnaeus, September 1, 1735, letter L0044 in The Linnaean correspondence (accessed March 11, 2008).

- ^ Carl Linnaeus to Johannes Burman, September 25, 1736, Letter L0093 in The Linnaean correspondence (accessed March 11, 2008).

- ↑ Les membres du passé dont le nom commence par L .

- ^ Richard Pulteney : A General View of the Writings of Linnaeus . London 1781, p. 77.

- ↑ Oratio qua peregrinationum intra patriam asseritur necessitas

- ↑ Barbara I. Tshisuaka: Linne (Linnaeus), Carl von. In: Werner E. Gerabek , Bernhard D. Haage, Gundolf Keil , Wolfgang Wegner (eds.): Enzyklopädie Medizingeschichte. De Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2005, ISBN 3-11-015714-4 , p. 856.

- ↑ Deliciae Natura . Tal hållit uti Upsala la Domkyrka. 1772. the 14th of December. vid Rectoratets nedlåggande. Stockholm 1773. German short review of the speech

- ^ William Thomas Stearn: Linnaean Classification, Nomenclature and Method . In: Wilfrid Blunt: The Compleat Naturalist: A Life of Linnaeus . 2004, p. 256. ISBN 0-7112-2362-9

- ↑ Peter Seidensticker: Plant names: Tradition, research problems, studies . Franz Steiner Verlag: 1999, pp. 33-36

- ↑ Axel Frederic von Cronstedt: Försök til Mineralogie, eller Mineral-Rikets Upställning . Wildisksa tryckeriet: Stockholm 1758 (published anonymously) German edition from 1770 .

- ↑ Michel Foucault : The order of things. An archeology of the human sciences. 14th edition, Frankfurt a. M. 1997, p. 166, ISBN 3-518-27696-4 .

- ↑ Michel Foucault: The order of things. An archeology of the human sciences. 14th edition, Frankfurt a. M. 1997, p. 175. (Source: Linné, Philosophia Botanica , § 299.)

- ↑ Quoted from Mädgefrau p. 70

- ^ "Species tot sunt, quot diversas formas ab initio produxit Infinitum Ens". In Paragraph 5 of the Ratio Operis from Genera Plantarum .

- ^ Han-liang Chang: Natural History or Natural System? Encoding the textual sign . 2004, p. 6 online (PDF; 107 kB)

- ↑ "Omnia Genera & Species naturalia sunt" ("The genera and species are all natural"). In Paragraph 6 of the Ratio Operis from Genera Plantarum .

- ↑ Linnaeus's Diary . In: Pulteney p. 548

- ^ Nils-Erik Landell: Linnés fjäril . In: Arte et Marte: Meddelanden från Riddarhuset . Volume 61, No. 1, 2007, pp. 6-7.

- ^ Member entry of Carl von Linné at the German Academy of Natural Scientists Leopoldina , accessed on April 17, 2017.

- ^ Linnaeus, Karl von (1757) . In: Werner Hartkopf: The Berlin Academy of Sciences. Its members and award winners 1700–1990. Akademie Verlag, Berlin 1992, ISBN 3-05-002153-5 , p. 220.

- ↑ entry on Linnaeus; Carl (1707–1778) in the Archives of the Royal Society , London

- ^ Foreign members of the Russian Academy of Sciences since 1724. Carl Linnaeus. Russian Academy of Sciences, accessed October 1, 2015 (Russian).

- ↑ WT Stearn: The background of Linnaeus's contributions to the nomenclature and methods of systematic biology. In: Systematic Zoology . Volume 8, No. 1, March 1959, pp. 4-22, here p. 4, online

- ^ Invalid banknotes. On: riksbank.se , last viewed on April 2, 2020.

- ^ Entry on the Linnaean Collections at the Linnean Society of London

- ^ The Linnaean Correspondence - Presentation

- ↑ Quoted from Karl Mägdefrau p. 71.

- ^ Julien Offray de La Mettrie: L'Homme Plante . In: Oeuvres philosophiques de La Mettrie . Volume 2, 1796, pp. 49-75

- ^ Johann Wolfgang von Goethe: History of my botanical studies , 1817

- ↑ Johann Wolfgang von Goethe: The metamorphosis of plants . In: Johann Heinrich Cotta (editor): Goethe's entire works in forty volumes. Complete, reorganized edition. (40 volumes in 20 volumes) . 1853-1858, Vol. 27, p. 102 online

- ↑ Online , Neue Zürcher Zeitung , NZZ, April 4, 2017 and Carl von Linné and his controversial image of women and races , Badische Zeitung , December 9, 2016

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Linnaeus, Carl von |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Linnaeus, Carolus (before being raised to the nobility); Linnaeus, Carl Nilsson (full name, prior to nomination); Dioscorides II. |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Swedish scientist who developed the foundations of modern taxonomy |

| DATE OF BIRTH | May 23, 1707 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Råshult |

| DATE OF DEATH | January 10, 1778 |

| Place of death | Uppsala |