Ludgate (city gate)

The Ludgate was a west gate of the medieval city wall of London and was demolished in the middle of the 18th century. The name is still preserved in the street name Ludgate Hill and the Ludgate Square off it. As in the name of the Ludgate Circus intersection . Ludgate stood at what is now St. Martin's Church on Ludgate Hill, halfway between the intersection of Ludgate Circus and St Paul's Cathedral . The place of the gate is marked by a plaque on the church.

Word origin

Contrary to the assertion of the Norman-Welsh Geoffrey of Monmouth in his Historia regum Britanniae , Ludgate ("Porth Llydd") was built by an old British king "Lud son of Heli" (see also the mythical figure Lludd ), the name of later authors optionally rather "floodgate '( Fluttor ) or after flowing near this point (now underground operations) River Fleet " Fleet gate "originating or" ludgeat "of or altenglisch " Hlid-geat "derived viewed what" back gate "or Sideline means.

history

The Romans built a road to the west along the north bank of the Thames , which presumably led through a gate later known as Lud-Gate, which is believed to have been part of the fortifications of Londinium . The gate is said to have watched over the street to the west, which led to the burial grounds of the Romans on today's Fleet Street. However, there is no archaeological or otherwise documented evidence that the Romans built a gate here.

John Stow, who wrote his Survey of Londoin in the 16th century , mentions the gate for the first time in research. He enumerated major repairs to the gate in 1216, 1260 and 1586, as well as a major expansion of the implemented prison in 1463.

The Ludgate was mentioned in the First War of the Barons , when the opponents of the king repaired or rebuilt the gate. They used stones from abandoned Jewish houses. One of the wall pieces bore the Hebrew inscription "This is the ward of Rabbi Moses, the son of the honorable Rabbi Isaac". In 1260 the gate was restored again. On the inner city east side, facing St Paul's Cathedral , sculptures depicting King Lud and his sons were installed and in the 16th century the west side was adorned with a representation of Queen Elizabeth .

As is common in many European cities, the city tower was also used as a guilty prison. In addition to Ludgate, the Newgate in London housed prisoners. In Ludgate, the “honor” of having to sit there to force his debt to be settled mainly went to the “ freemen ” of London. Clergymen were also imprisoned here for minor offenses. In 1419 the guilty prison was closed and the prisoners were transferred to Newgate prison . The reason was the abolition of the status of prison for Freemen due to the increasing acceptance of less “honest” citizens (“false persons of bad disposition”). Within just a few months, an unspecified number of those who had been transferred died in Newgate Prison; her death was placed at the expense of the “fetid and corrupt atmosphere” in Newgate, so that it was closed for a few years and the Ludgate was reactivated.

The tower had a lead-roofed roof on which prisoners could move in the fresh air and a large room at floor level where they could walk around. In the 1450s and 1460s the gate was enlarged by Sir Stephen Foster , Lord Mayor of London from 1454. In the year of his mayor's office, he and his wife Agnes began to renovate and expand the gate as well as the debt prison. After his death in 1458, his widow continued the project until it was completed in 1463 and also obtained the abolition of the previous ordinance with the Lord Mayor in charge of that year, Matthew Philip, according to which debtors had to pay their own board and lodging. A brass plaque there reminded of their patronizing work. In the 17th century, presumably due to the city fire and reconstruction, they no longer existed.

“Devout souls that pass this way, For Stephen Foster, late mayor, heartily pray; And Agnes, his spouse, to God consecrate, That of pity this house made, for Londoners in Ludgate; So that for lodging and water prisoners here nought pay, As their keepers shall answer at dreadful doomsday! "

Nevertheless, the guards still had an easy job when it came to taking advantage of themselves. Food was sold to prisoners at a high price and prisoners were tortured to support their greed - sometimes on behalf of their creditors, who paid for it. This was done with heavy irons that were placed on or on the prisoners, sticks, or sleep deprivation. It happened, however, that the guards had to justify themselves to the court when they were discovered and were also punished.

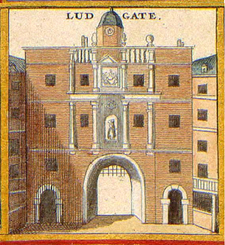

The building

The tower, as it was built between 1454 and 1468 after it was demolished and rebuilt, was 13.6 meters long and 11 meters wide. With a wall thickness of 0.9 meters each, the prisoners had "sufficient" space to move around (according to the standards of the time), which was not possible before the renovation. Above were the cells and stairs led to the top floor, where the prisoners got sunlight and fresh air. The height of the Ludgate is unknown.

In 1554 Ludgate Prison had 30 prisoners. In 1586 it was demolished and rebuilt at a cost of £ 1,500.

During the Great Fire of London in 1666, the gate was badly damaged, burned out inside and had to be rebuilt. It received a three-story prison, a guard room and a bell tower.

A description of the prison from 1725 contains the following information [loosely translated, with omissions] :

“The gate rises with a simple arched passage for carriages and wagons. There are pedestrian entrances on each side. The front facing east towards St. Paul is adorned with the statues of King Lud and his two sons; opposite the statue of Queen Elizabeth adorns Fleet Street. […] The roof is covered with lead, which is crowned by a tower in which there is a clock with two dials, one facing each side. On the south side is a building erected by Dame Agnes Foster, also with lead roof, on which the prisoners have the freedom to walk around to refresh themselves; this part is now called the "common side", more on this later. We have seen the outside, let's go inside: we do this through a large door that is directly at the southern side entrance [for pedestrians]. When we have climbed 6 steps, the first thing we see is a large box with a painted inscription.

"There are to satisfy all that are willing to give their Charity to this House, that the Money is put into this Box, which hath Three Locks; one Key being kept by the Keeper, another by the Master of the Box, and the third by the Assistant of the Day; and no money to be taken out without their mutual consent, to be justify destributed among the Prisoners. "

Opposite on the left is a small door that opens into the office, which is called that because all prisoners ... [are recorded there]. Behind it there is another room in which the prisoners are allowed to move freely. […] The next thing that can be seen is a hatch that opens into the prison, in which, if you turn to the right, you come to a room called Lumbry , where on the left a door leads to the sticks that offenders use to get punished. One or the other prisoner stands at a large window to beg the passers-by for money. […] A little further on there is a door on the right, where the stairs lead to the basement, in which drinks and tobacco are sold to the inmates , but without having the opportunity to write. However, it must be said that he who drinks abundantly and encourages others to do the same receives credit; but if he asks about it out of necessity, he shouldn't get a pint of beer to help him out. Opposite the cellar stairs is the large cistern , which is supplied from the Thames . In the past this was done from a source as ordered by Dame Agnes . A little further is an iron grating, which opens to the south gate, where some prisoners also beg passers-by for money. In the corner of the basement stairs is a neat staircase, illuminated by a large skylight; after 11 or 12 steps you can see a small room above the side gate, which is called XVIII and sometimes serves as a drinking room; then two other rooms that are now occupied by the cellar guard […] A few steps higher is the third floor, which, as soon as you have reached it, opens a door into a large room called the White Room , furnished with one long table and benches and a large fireplace, where every Sunday broth with whole pieces is a special treat for the prisoners [...] "

Like most of London's city gates, Ludgate was demolished in 1760. The attached statues of King Lud, his sons and Queen Elizabeth I were moved to St Dunstan's-in-the-West Church on Fleet Street, where they can still be seen today. The remains of the gate sold for £ 148 on July 30, 1760.

In the literature

- Ludd's Gate is mentioned in Bernard Cornwell's historical novel Sword Song , which is set in the reign of Alfred the Great .

- The pseudo-historical work Geoffrey of Monmouths Historia Regum Britanniae , written around 1136, claims the name comes from a Welsh king named Lud (Son of Heli), who is said to have given his name to London.

- In his fictional novel "A New Wonder, a Woman Never Vexed" from 1631, William Rowley describes the story of getting to know Stephen and Agnes Fo (r) ster in Ludgate prison.

- Ludgate appears in Walter de la Mares' poem "Up and Down", from Collected Poems 1901–1918 , Volume II: Songs of Childhood, Peacock Pie, 1920.

- The prison is mentioned in Daniel Defoe's 1724 novel Roxana: The Fortunate Mistress .

Individual evidence

- ^ Walter Thornbury: Ludgate Hill . In: Old and New London: Volume 1 . Institute of Historical Research. 1878. Retrieved July 30, 2020.

- ↑ Gillian Bebbington: London Street Names , Batsford Books (today Pavilion Books), London 1972, ISBN 978-0-7134-0140-0 ( 207 online )

- ↑ Charters of Abingdon Abbey, Volume 2 , Susan E. Kelly, Published for the British Academy by Oxford University Press, 2001, ISBN 0-19-726221-X , 9780197262214, pages 623-266

- ^ Geographical Etymology , Christina Blackie, p. 88

- ^ English Place-Name society, Volume 36, The University Press, 1962, p. 205

- ^ Middle English Dictionary, University of Michigan Press, 1998, pp. 972, ISBN 0-472-01124-3

- ^ William Kent: An encyclopaedia of London , Dent 1951, pages 402 ff.

- ↑ [... excavations at 42-6 Ludgate Hill and 1-6 Old Bailey, London EC4], PDF 8.19 MB

- ^ John Stow: Survey of London , Ed. CL Kingsford, 1908, pp. 38-39

- ↑ a b John Timbs: Curiosities of London , London 1867 ( online )

- ↑ London Metropolitan Archives Journal 1, f. 57v; CCR, 1409-1413, p. 215; LBI, p. 215; Memorials, pages 673-674.

- ↑ London Metropolitan Archives Journal 1, f. 65; LBI, p. 227; Memorials, p. 677

- ↑ Caroline M. Barron, 'Forster, Agnes (d. 1484)', Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Jan 2008 accessed 22 May 2017

- ↑ a b The Present State of the Prison of Ludgate…, 1725 in the Google book search

- ↑ The National Archives C1 / 67/142, 1483–1485, "Robert Fossell, a debtor in Ludgate, was loaded with irons and prevented from sleepin."

- ^ R. Baldwin: The London Magazine, Or, Gentleman's Monthly Intelligencer , Volume 29, London 1760 online in the Google book search

- ↑ London Metropolitan Archives, Rep. 10, f. 71b (1538).

- ↑ a b Kings, hills and prisons | The story behind Ludgate in the City of London (Blog)

- ^ Thomas Pennant : Some Account of London , 1790; (5th edition 1813), p. 318

- ^ Neil Wright: The Historia Regum Britannie of Geoffrey of Monmouth , Boydell and Brewer, Woodbridge 1984, ISBN 978-0-85991-641-7 , pages xvii – xviii, quotation: “... the Historia does not bear scrutiny as an authentic history and no scholar today would regard it as such. "

- ↑ London ( Memento of April 15, 2009 in the Internet Archive )}

Coordinates: 51 ° 30 '50.3 " N , 0 ° 6' 8.1" W.