Lufthansa flight 005

| Lufthansa flight 005 | |

|---|---|

|

The structurally identical Lufthansa D-ACAD aircraft at Copenhagen Airport (March 1968) |

|

| Accident summary | |

| Accident type | Stall when taking off |

| place | Stuhr |

| date | January 28, 1966 |

| Fatalities | 46 |

| Injured | 0 |

| Aircraft | |

| Aircraft type | Convair CV-440 |

| operator | Lufthansa (LH) |

| Mark | D-ACAT |

| Passengers | 42 |

| crew | 4th |

| Lists of aviation accidents | |

The Lufthansa flight 005 on 28 January 1966 was a scheduled flight of Lufthansa from Frankfurt to Hamburg with a stopover in Bremen . During a go- around maneuver , the twin-engine propeller plane crashed shortly before 7 p.m. behind the runway at Bremen Airport from a low height on a field belonging to the municipality of Stuhr . In the fall , all 42 were passengers and the four crew members killed.

The cause of the accident could not be clarified beyond doubt, especially since the aircraft was not equipped with a flight recorder .

Aircraft

The 1958 built Convair CV-440 Metropolitan was operated with the aircraft registration D-ABAB from July 18, 1958 by Deutsche Flugdienst GmbH ( renamed Condor Flugdienst on November 1, 1961 ). Lufthansa took over the short-haul aircraft on November 7, 1961 with the new registration D-ACAT. In the accident, the Convair had 13,871 flight hours of operation.

the accident

With a slight delay of eight minutes, the plane took off at 17:41 on Friday, January 28, 1966 from runway 25R at Frankfurt Airport in the direction of Bremen. The take-off weight was 22,148 kg and thus almost corresponded to the maximum take-off weight of 22,544 kg specified for this type . With the tank supply of 3200 liters of aviation fuel , a flight time of 5 hours and 13 minutes would have been possible. This high stock was necessary because the two pilots had chosen Stuttgart Airport as a safe alternative destination because of the bad weather conditions in the north of Germany .

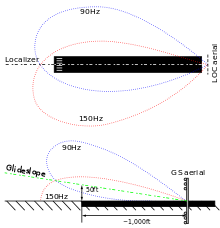

After a cruise of around 30 minutes at flight level 140 (14,000 feet (ft), corresponds to 4270 meters), the approach to landing from the east on runway 27 at Bremen Airport began at 18:40 . The temperature was +4 degrees Celsius , the cloud base was below 100 meters. Because of the heavy rain, the ground visibility was only about 700 meters. The wind speed was nine knots from the direction of 140 degrees. The resulting tailwind component that acted on the machine during landing was six knots. For its Convair 440, Lufthansa allowed a maximum of five knots of tailwind when approaching runway 27 at Bremen Airport under minimum weather conditions. In the 1960s, Bremen Airport was not yet equipped with a precision approach radar (PAR) for ground-controlled approaches ( GCA ).

The 48-year-old flight captain Heinz Saalfeld started the final approach , but initiated a go-around maneuver during the overflight at a height of about ten meters , which the crew no longer reported to the tower . Tipping to the left and heading in the opposite direction to runway 27, the 21.5-ton machine hit the ground at 6:51 p.m., 380 meters south of the center of the runway and 400 meters west of the runway end at the time. According to a contemporary newspaper report and the associated aerial photo, the impact location was 280 meters almost exactly south of the end of the runway and thus 372 meters east-southeast of the position specified in the investigation report. On impact, the remaining aviation fuel of approx. 2500 liters ignited and caused a conflagration which the airport fire brigade could extinguish after 40 minutes.

At the time, the accident in Bremen claimed the most victims since the company was founded in 1954 and was its fourth total loss: after the crash of a Lockheed Super Constellation while approaching Rio de Janeiro / Galeão airport on January 11, 1959 with 36 victims ( Lufthansa flight 502 ) the airline lost two Boeing 720-030Bs during training flights over the Federal Republic of Germany in 1961 and 1964 , with all three crew members perishing (see also: Lufthansa incidents ).

causes

The Luftfahrt-Bundesamt (LBA) submitted its final report about a year later and came to the conclusion that the crash was a combination of technical and human errors.

The report is to be assumed that the gauge of the ILS system in the cockpit indicated wrongly, so that the machine in instrument flight (colloquially known as "flying blind") above the prescribed glide path flew (glideslope). When flight captain Saalfeld switched to visual flight after breaking through the low cloud cover (300 feet corresponds to approx. 91 m) , he underestimated the remaining height above ground in the dark and poor visibility and thus flew over the correct touchdown point of the 1909 meter long runway 27 at Continuing the descent , the machine would not have come to a standstill after touching down on the remaining available runway, as 1515 meters would have been required for the current landing weight (with a maximum of 5 knots of tailwind and 22 degree position of the landing flaps ). After flying over half the length of the runway, the flight captain therefore decided to take off and initiate the missed approach procedure. When he returned to instrument flight, he probably maneuvered the Convair into an " excessive flight condition ", which led to the current breaking off and the machine hitting the ground with the bow and left wing first. Except for the tail section and the right wing, the aircraft was completely destroyed.

The investigation showed that the landing gear was retracted and locked and the landing flaps were in the 15 degrees position. The speed controllers of the two P & W R-2800 CB-17 engines, each with 1863 kW starting power (2534 PS), which were not found to be malfunctioning, were set to METO output (maximum power except take-off). It can be assumed that the crew switched the engines back from take-off to METO power when they noticed the Convair tipping over. No errors could be found in other safety-relevant systems such as airframe and controls .

Investigations by the manufacturer Convair in 1955 on the flight behavior of the CV-440 Metropolitan showed that the type shows a tendency to roll to the left when the flaps are extended and this is even more pronounced when the flaps are extended and the engine power is higher. In order not to exceed the flight range limits, the roll angle must be corrected immediately with strong ('heavy') actuation of the ailerons when the stall warning system is used (shaking the control horn ) . The stall behavior of the CV-440 was therefore rather moderate and, especially in low speed ranges, classified as critical.

According to an article in Der Spiegel magazine , the plane was considerably iced up when it landed and visibility for the pilots was almost impossible. According to the accident report, it could not be ruled out that the master had a cardiovascular disorder in the critical landing phase and could no longer operate the machine safely. Because of the low altitude, the first officer (co-pilot) Klaus Schadhof was then no longer able to intercept the machine. A forensic-toxicological examination of the remains of the pilot in command (PIC) was not possible; the corresponding examination of the corpse of the copilot showed a blood alcohol concentration of 0.24 parts per thousand .

Various hypotheses were made about the course of the D-ACAT crash, but no specific reason could be determined and the investigation report ended with the sentence: "Other causes may have contributed to the accident."

Flight captain Saalfeld had been in possession of the commercial pilot's license since August 28, 1958 and had received the last flight medical certificate (Flight Medical) on August 16, 1965. Of his 5095 hours of flight experience, 1,187 hours were in command of the Convair CV-440. In addition, he had the type rating for the turboprop engine Vickers Viscount . The 27-year-old co-pilot Klaus Schadhof had been in possession of a second-class professional pilot's license since 1965 and had 793 hours of flight experience, 533 of which as a co-pilot on a CV-440. His last flight medical was on January 4th, 1966.

Victim

On board the machine, which was designed for 53 passengers, sat, among others, seven swimmers from the Italian Olympic team, their trainer and an Italian reporter, who traveled to the 10th International Swimming Festival of the Bremen Swimming Club (BSC from 1885), which took place on the Richtweg in the following days in what was then the Zentralbad (today the location of the Metropol Theater Bremen ) took place. The following year, not far from the crash site, the Olympic Committee and the Swimming Association of Italy erected a stele with the names of their compatriots who had died in memory of these victims . The stone, unveiled on March 4, 1967, was moved to its current location on Norderländer Straße in 1991 . On May 18, 2019, a second stele with the names of all 46 victims was unveiled at the same location.

Actress Ada Chekhova , daughter of Olga Chekhova and mother of Vera Chekhova , was also among the victims.

Park to the left of the Weser : Memorial next to the car park on Norderländer Straße

Memorial stone from 1967 of the Olympic Committee and the Swimming Association of Italy (back, front with Italian inscription )

literature

- Helmut Kreuzer: Crash - The fatal accidents with passenger aircraft in Germany, Austria and Switzerland (since 1950) . 1st edition. Air Gallery Edition, Erding, 2002, ISBN 3-9805934-3-6 .

- Stern , issue 7/1966 from February 13, 1966

- Lufthansa: Silence on the radio . In: Der Spiegel . No. 6 , 1966 ( online - Jan. 31, 1966 ).

- Imke Molkewehrum: Meticulous search in the rubble field. In: Bremer Tageszeitungen - Kurier am Sonntag , No. 6 of February 12, 2012, p. 30

Web links

- UFA-Wochenschau 497/1966 from February 1, 1966; Film report from 5:30

- The Lufthansa D-ACAT plane crashed in Bremen at Düsseldorf Airport (photos from 1964/65)

- Accident report CV-440 D-ACAT , Aviation Safety Network (English), accessed on February 20, 2019.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Thomas Walbröhl: Landing in the death. In: Weser Kurier, January 28, 2016, p. 10 (The height information is contradictory.)

- ↑ ICAO Aircraft Accident Digest No. 17 Volume II, Circular 88-AN / 74, Montreal 1969 (English), pp. 42-54.

- ↑ Frank Hethey: No more answer from Lufthansa flight 005 ( memento from April 30, 2018 in the Internet Archive ) on bremen-history.de - 50 years ago, from January 31, 2016

- ↑ Luftfahrt-Bundesamt : D-ACAT accident report on baaa-acro.com (English; PDF; 8.9 MB), accessed on September 16, 2019

- ↑ Peter-Philipp Schmitt: Im Blindflug in den Tod , In: FAZ from January 28, 2016

- ↑ Erika Thies: Commemoration of the victims , In: Weser-Kurier from January 28, 2016

- ↑ Memorial stone for the 46 victims of the plane crash in Stuhr. May 20, 2019, accessed May 21, 2019 .