gastroenteritis

| Classification according to ICD-10 | |

|---|---|

| A09.- | Other gastroenteritis and colitis of infectious and unspecified origin |

| ICD-10 online (WHO version 2019) | |

As gastroenteritis , literally gastrointestinal inflammation - commonly gastrointestinal flu , diarrhea and vomiting or stomach flu - is an inflammatory disease of the gastrointestinal tract called. A gastrointestinal flu is usually accompanied with vomiting and diarrhea, but with the "real flu" ( influenza nothing to do). Gastroenteritis can have several causes. If the stomach is not affected, one speaks of enteritis (outdated, especially in acute enteritis, also called intestinal catarrh ).

Epidemiology

Gastroenteritis or gastrointestinal inflammation of various causes are the most common causes of diarrhea and nausea in children and adults. In 1980, diarrhea was the leading cause of child mortality worldwide, with an estimated 4.6 million deaths each year. Since the so-called oral rehydration therapy was made known as a standardized treatment in 1979 , this number has been reduced to around 1.5 million in 2000.

causes

The causes of gastrointestinal flu are many. They range from infections to chemical-toxic stimuli (poisoning) to physical (e.g. thermal) causes. In most cases, bacteria or viruses are responsible for gastrointestinal flu. They damage the lining of the digestive system either directly or indirectly through bacterial toxins. The gastrointestinal flu is transmitted by the oral route (partly fecal-oral smear infection). The mucous membranes can also be damaged by ionizing radiation, such as X-rays or radiation from radioactive material.

Infections

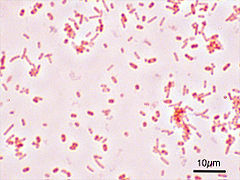

The most common cause of acute inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract are local infectious diseases caused by viruses (such as rota , adeno , human noroviruses , sapoviruses and astroviruses ; see also Enterovirus ), bacteria (such as salmonella , campylobacter , shigella , yersinia , clostridium difficile , Bacillus cereus , Escherichia and Vibrio cholerae ) or protozoa (such as amoebas , giardia ). The mechanism by which infection caused by contaminated food in enteritis leads to symptoms may vary. The pathogens predominantly lead to the destruction of the mucous membrane to varying degrees. As a result, the stomach and intestines can no longer digest food. The undigested food binds water and makes the stool thin. With some bacterial gastrointestinal infections ( bacterial gastroenteritis or bacterial enteritis ), the production of bacterial poisons (toxins) by the pathogens leads to increased salt and water loss through the mucous membrane cells of the intestine. This is the case, for example, with a special variety of Escherichia coli bacteria, a pathogen that causes typical traveler's diarrhea .

- Typical pathogens of infectious gastroenteritis

Toxins

If only the bacterial toxin accumulates in a spoiled food, this toxin can also lead to inflammation of the mucous membrane after consuming the corresponding food. The result is the picture of classic food poisoning . The toxin of certain staphylococci can be an example of this . Medicines and other toxins can also lead to toxic gastroenteritis.

Ionizing rays

Ionizing rays ( X-rays , radioactivity ), for example in the event of a reactor accident or as part of cancer treatment, also severely damage the mucous membrane of the gastrointestinal tract, which constantly renews itself at high speed, so that its digestive function is also impaired can no longer fully perceive ( radiation colitis ).

transmission

In the case of most infectious gastroenteritis, the transmission takes place via so-called fecal-oral smear infection . Infectious stool, for example, finds its way into the food through insufficiently cleaned hands and then through the mouth back into the gastrointestinal tract of the next patient. In the case of Salmonella, enrichment must usually also take place. This means that the pathogens have to multiply through longer storage of the food so that the minimum infection dose is reached. In the case of toxic gastroenteritis caused by bacterial exotoxins, too, the toxins are ultimately “transmitted” through food. Only noroviruses are so infectious that when the patient vomits in a surge, the finest droplets containing pathogens can float in the air, which are ingested by relatives or the nursing staff and can lead to an infection ( droplet infection ).

incubation period

The incubation period (time between ingestion of the pathogen and the first symptoms) can extend over a period of 4 to 48 hours.

Symptoms

In the case of infectious gastroenteritis in particular, the pathogen usually migrates from top to bottom through the gastrointestinal tract. Therefore, the disease usually begins with loss of appetite, nausea and / or vomiting. Diarrhea usually occurs after a few hours, while the stomach symptoms can then subside. The diarrhea can also be bloody, depending on the extent of the damage to the mucous membranes. The bowel movements are increased during the diarrhea, which can lead to cramping abdominal pain. Fever as a general symptom of an infection as well as dizziness and exhaustion also occur in this phase. In the case of persistent vomiting and diarrhea, the symptoms of dehydration ( desiccosis ) can also occur due to the loss of fluid and the impaired fluid intake .

Diagnosis

The diagnosis can be made for the doctor through the typical anamnesis . A stool inspection can back up the diagnosis. The detection of causative pathogens by means of a microbiological examination is of epidemiological interest. A stool exam is recommended if the following conditions exist:

- Relevant comorbidities

- Immunosuppressed patients

- Bloody diarrhea

- Severe clinical picture (e.g. fever , dehydration , sepsis )

- Hospitalization for gastroenteritis

- Patients who work in community facilities or with food

- People on antibiotics within the last three months

- Before initiating antibiotic therapy

- If an accumulation is suspected that suggests an epidemiological connection

It should be tested in the outpatient area for Campylobacter , Salmonella, Shigella and Noroviruses. If there are risk factors for a Clostridium difficile infection, this pathogen should also be tested. A stool examination should also only be carried out for those returning to travel under the conditions mentioned above. In contrast to the examination of people who are believed to have been infected in Germany, a first examination for campylobacter, shigella, salmonella, lamblia and amoeba is to be carried out on returning travelers and a second examination for Yersinia, mycobacteria, cryptosporidia, Isospora belli and helminths .

A blood test can help estimate the amount of water and salt being lost. In the course of this, however, weight checks are most informative.

Complications

In children in particular, the loss of fluids and minerals (electrolytes) can lead to an increasing dehydration of the body with a corresponding weight loss. If left untreated, circulatory problems ( shock ), kidney failure or seizures can occur. Also predominantly in children, the increased mobility of the intestine can also result in an inversion of the intestine in itself ( intussusception ).

prophylaxis

First and foremost, hygienic measures, especially when preparing food, are part of the prophylaxis of gastroenteritis. The fact that many infectious gastroenteritis hardly play a role in developed countries shows the importance of hygiene in the prevention of these diseases. There are also vaccinations for individual pathogens, for cholera or typhus . Several vaccines for young children are approved for human rotavirus . Since August 2013, oral vaccination against rotaviruses has been recommended for infants from the age of six weeks in Germany.

therapy

Since treatment in the form of eliminating the cause is usually not possible, therapy is usually limited to symptomatic measures. These consist primarily of replacing the loss of fluid and salt caused by vomiting and diarrhea. Ideally, patients are offered standardized solutions with a mixture of glucose and salt ( WHO rehydration solution ). If this form of replenishing the fluid balance (“rehydration”) does not succeed, an infusion may also have to be given, especially in children who are particularly at risk of dehydration . A careful diet from the beginning can promote the recovery of the destroyed intestinal mucosa and should be tried from the beginning in the form of easily digestible carbohydrates (rusks, pretzel sticks, white bread, bananas). The initial food pause recommended earlier statistically leads to an increase in the duration of the diarrhea, which can be explained by the fact that on the one hand the intestine takes the building blocks for reconstruction directly from the food supply, on the other hand an organ that has been shut down ( food abstinence ) has no incentive to resume its function. A meta-study came to the conclusion that so-called probiotics could possibly shorten the duration of diarrhea by eight hours to one day. These are bacterial strains (for example Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus ) that are natural colonists and can be administered in freeze-dried form (powder, tablet) or as an additive in a ready-to-use rehydration solution. Medicines that inhibit vomiting ( antiemetics ), alter bowel function ( opiates , such as loperamide ) or paralyze it ( parasympatholytics , such as butylscopolamine ), can be used as supportive symptomatic measures . However, the possible side effects must be taken into account and the risk carefully weighed against the possible benefit. Because of the often self-limiting course of bacterial enteritis, antibiotic treatment should only be considered in exceptional cases with a septic course, even if bacteria are detected as the causative pathogen , as this significantly increases the rate of permanent excretors , especially in the case of Salmonella infections .

Economic impact

Gastroenteritis and other diarrheal diseases can cause significant financial damage and exacerbate poverty. This is particularly the case in the less developed countries south of the equator. The financial loss is particularly influenced by the costs of medical treatment, medication, transport to the doctor, special food, and loss of work and earnings. In quite a few cases, affected families have to sell their entire land to pay a hospital bill. On average, an affected family pays around 10% of their monthly income per infection and person.

Reporting requirement

According to the Infection Protection Act, there is an obligation to report in Germany if cholera , typhoid and paratyphoid fever is suspected , and especially if there is an actual illness or death. In all other cases of microbial food poisoning or infectious gastroenteritis, the suspected case must be reported if either a person is affected who processes food or is employed in a kitchen, restaurant or other communal catering facility, or if two or more similar diseases occur in which an epidemic connection is suspected. In addition, the detection of various gastroenteritis pathogens (Campylobacter, intestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli, Giardia lamblia, human noroviruses, rotaviruses, all salmonella types, Shigella, Vibrio cholerae, Yersinia) must be reported. In addition, there is an obligation to register children who have not yet reached the age of 6 and who attend a community facility ( day-care center, etc.). ( Section 34 (6 ) IfSG)

Veterinary medicine

In addition to the pathogens already mentioned, acute gastroenteritis in domestic animals can be an expression of serious infectious diseases such as parvovirus and distemper (dog), panleukopenia (cat), Aleutian disease ( ferret) or wet-tail disease (hamster), which require intensive medical care and often with it end in the death of the beast.

literature

- Marianne Abele-Horn: Antimicrobial Therapy. Decision support for the treatment and prophylaxis of infectious diseases. With the collaboration of Werner Heinz, Hartwig Klinker, Johann Schurz and August Stich, 2nd, revised and expanded edition. Peter Wiehl, Marburg 2009, ISBN 978-3-927219-14-4 , pp. 179-182 ( infections of the gastrointestinal tract ).

- Hans Adolf Kühn: Inflammatory bowel diseases. In: Ludwig Heilmeyer (ed.): Textbook of internal medicine. Springer-Verlag, Berlin / Göttingen / Heidelberg 1955; 2nd edition ibid. 1961, pp. 810-821, here: pp. 810-812 ( diffuse, non-ulcerative inflammation ).

Individual evidence

- ↑ CG Victora et al .: Reducing deaths from diarrhea through oral rehydration therapy. In: Bulletin of The World Health Organization. 2000, 78, pp. 1246-1255 PMID 11100619 .

- ↑ Marianne Abele-Horn (2009), p. 179.

- ↑ a b A. Stallmach, S. Hagel, AW Lohse: Diagnosis and therapy of infectious diarrheal diseases . The internist, 2015.

- ^ W. Van Niel et al.: Lactobacillus Therapy for Acute Infectious Diarrhea in Children: A Meta-analysis. In: Pediatrics. 2002, 109, pp. 678–684 full text online (English)

- ↑ B. Schnabel: Fatal diarrhea. In: Development and Cooperation. 2009, 4, pp. 162–163 full text online (German)