Mary Kingsley

Mary Henrietta Kingsley (born October 13, 1862 in Islington , † June 3, 1900 in Simon's Town , South Africa ) was a British explorer , ethnologist , travel writer and lecturer who had a lasting influence on British ideas about West Africa and its people.

Life

Domestic situation

Mary Kingsley was the daughter of doctor George Henry Kingsley (a brother of writer Charles Kingsley ) and his domestic servant, cook Mary Bailey.

The parents' marriage, which concluded four days before their daughter Mary was born, was considered improper due to class differences, and Mary Bailey Kingsley was largely ignored by her husband's family, with the exception of his brother Henry. George Henry Kingsley himself was rarely at home; As a personal physician, he often accompanied mostly noble employers (including the Earl of Pembroke ) on their travels. Mary's brother Charles George Kingsley was born in 1866.

While the brother was able to go to school and then study, Mary Kingsley spent most of the time with her mother, who later needed care, at home, with the windows of the house usually darkened at the mother's request. She never went to school; the only formal education her father financed for her was private German lessons so that she could support him in his hobby ethnology studies. In addition, she acquired her knowledge mainly from her father's library. She read books on physics, chemistry, geography, ethnology and theology, as well as travel and adventure literature and do-it-yourself magazines.

The family moved to Cambridge in 1886 . It was here that Mary Kingsley began to represent her nervous mother as the hostess at the tea parties and scholarly circles of her now permanently returned father, and she succeeded for the first time in building up her own circle of friends outside the home.

In the spring of 1892, Kingsley's father and then her mother died six weeks apart. Kingsley, who for the first time was free from family responsibilities as well as without a task, soon afterwards decided to go on a journey. Motivated by her reading, she chose West Africa; her first test trip took her to the Canary Islands in 1892 . Then she did a short training in nursing in the deaconess institution in Kaiserswerth . The skills she acquired helped her on the one hand to maintain her own health, and on the other hand she was able to acquire friendships and recognition through minor medical assistance.

Travel to Africa

Kingsley set out from England in August 1893 on a cargo ship to Africa. She then sailed along the coast via Freetown in Sierra Leone to Angola . At Cabinda , on the island of Fernando Póo and the lower Congo , she carried out her first ethnological field studies. She lived there with locals, from whom she learned useful skills for her travels in the African jungle , among other things .

Her route took her via the French colony of Congo (now Gabon ) to Calabar , from where she returned home in January 1894. Their reports aroused interest and they established contacts with the British Museum . The zoologist Albert Günther of the British Museum equipped her with equipment for the following trips and got her a book contract.

After preparations for a second voyage, Kingsley set out on December 23, 1894 with the Batanga from Liverpool on her next expedition . It reached the French colony of the Congo again via the Gold Coast and Old Calabar. She first took a steamboat, then a canoe up the Ogooué river , collecting fish some of which had not yet been cataloged in Europe. Accompanied by indigenous guides and porters, Kingsley then took a route through the bush to the banks of the Remboué River. She traded British fabrics and metal goods for rubber and ivory , on the one hand to finance her stay and on the other to make it easier to talk to people. On the trip she also made friends with British traders, especially the palm oil traders from the Liverpool area, who were rather rowdy in the white colonial society . After their expedition through the bush, Kingsley drove back to the coast, to Corisco and to the former German colony of Cameroon . She was the first European woman to climb the 4,095 m high volcanic Cameroon mountain , West Africa's highest peak , again accompanied by indigenous porters and travel guides . In November 1895 she started her journey home from Cameroon via Calabar.

Upon her return, Kingsley described her journey in dazzling colors and with self-deprecating humor in her 700-page travelogue Travels in West Africa . In addition to extensive ethnological considerations and geographical descriptions, the book contains numerous anecdotes about Kingsley's experiences with supposed and real dangers on water and on land, friendly and unsuccessful contacts with members of the West African people of the Fang as well as encounters with leeches , hippos , gorillas , elephants and crocodiles . A wildlife trap mishap reads like this:

“About five o'clock I was off ahead and noticed a path which I had been told I should met with, and, when met with, I must follow. The path was slightly indistinct, but by keeping my eye on it I could see it. [...] I made a short cut for it and the next news was I was in a heap, on a lot of spikes, some fifteen feet or so below ground level, at the bottom of a bag-shaped game pit.

It is at these times you realize the blessing of a good thick skirt. Had I paid heed to the advice of many people in England, who ought to have known better, and did not do it themselves, and adopted masculine garments, I should have been spiked to the bone, and done for. Whereas, save for a good many bruises, here I was with the fulness of my skirt tucked under me, sitting on nine ebony spikes some twelve inches long, in comparative comfort, howling lustily to be hauled out. [...] The Passenger came [...], and he looked down. 'You kill?' says he. 'Not much,' say I, 'get a bush-rope and haul me out.' ”

She left the insects, reptiles and fish that she collected or had collected on the trip to the British Museum .

Lectures and books

News of her travels soon reached England and her return in November 1895 met with great public interest. Her book Travels in West Africa became a bestseller soon after its publication and made her a sought-after traveling speaker. In the following three years she gave numerous lectures on life in Africa, its fauna, flora and "folklore".

Kingsley wrote next to her travel report Travels in West Africa (1897) with the more political work West African Studies (1899) another book about her trip. She saw the former as a contribution to the discussion of British colonial practice; Here she also discussed her thoughts on a possible future for the administration of the British colonies. In doing so, it relied more on self-government than the Colonial Ministry, which was meanwhile centralized under Joseph Chamberlain ; nonetheless, Kingsley clearly saw herself as an imperialist and a colonialist. Her aim was not to abolish colonialism, but to reform it and, not least, make it more lucrative for Great Britain. The work received wide reviews; In political circles, however, the reception of their ideas, which were regarded as out of date, fell short of their hopes.

The missionaries of the Anglican Church , they strongly criticized for their attempts Africans to "Europeanize". She did not want practices like polygamy and cannibalism , which shocked white Europeans, to be abolished, but tried to explain them. It was different with the practice of killing twin children , which was widely found in Calabar ; Here she endorsed the work of persuading the Scottish missionary Mary Slessor , with whom she was a good friend. Their cultural relativism feeds on a differentialist and at the same time hierarchical notion of human “ races ”. As a result, was "a. Black man [...] no more hare of undeveloped white man than a rabbit is an undeveloped" A ban on the sale of alcohol to Africans as abstainers aspired, she also declined - not least because they on her travels made close and friendly contacts with Liverpool traders who made a living from the gin trade. She had no sympathy for the contemporary suffragette movement , as her conception of the sexes was just as differentialistic as her “race” ideology: “[T] the mental difference between the two races is very similar to that between men and women among ourselves. A great woman, either mentally or physically, will excel an indifferent man, but no woman ever equals a really great man. "

At the end of her life

Kingsley had planned a third trip to the west coast of Africa, but changed their plans after the outbreak of the Boer War . Instead, she went to South Africa and offered her services as a nurse. She died at the age of 38 of typhus in Simonstown near Cape Town in a POW camp, where she treated interned Boers .

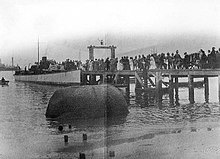

As she had wished, Mary Kingsley was buried at sea; she was the first woman to receive military honors.

meaning

Kingsley's field research brought a great deal of information about the way of life of West African people to Europe in the 1890s with what were then relatively new ethnological working methods. She also understood her work to be entirely political: She argued against the prevailing notion in Europe and America at the time that black people were “primitive” and that Europe had to “civilize” Africa. Parts of her work are quite contradictory; so it never questioned the ideology of “white” supremacy and expansive European imperialism. At the same time, their will to understand Africans on the basis of new research methods at the time - not least through their lively narrative style - also contributed to a more differentiated picture of the people in West Africa in England.

Kingsley's political significance is seen in two ways: she was an actor in British colonialism; at the same time, their sincere interest was also appreciated by the indigenous population. She had no direct influence on British colonial policy; However, their work is indirectly seen by researchers as one of the foundations for the later activities of critics of colonialism such as Edmund Dene Morel , who Kingsley himself referred to as his "mentor".

Works (monographs)

- Travels in West Africa , London: Macmillan 1897.

- West African Studies , London: Macmillan 1899.

- The Story of West Africa , London: Horace Marshall 1900.

- Notes on Sports and Travel , London: Macmillan 1900.

Publications in German

-

The green walls of my rivers, records from West Africa , excerpts and photographs from Travels in West Africa , London 1897, C. Bertelsmann, Munich 1989, ISBN 3-570-02655-8 .

- as dtv paperback, Munich 1992, ISBN 3-423-30315-8 .

- Travels in West Africa, Through French Congo, Corisco and Cameroon , Edition Erdmann , 4th edition, Lenningen 2016, ISBN 978-3-86539-861-1 .

documentation

- Tropical fever - risk in the jungle. Mary Kingsley among cannibals , soundtrack - Vangelis - Mutiny on the Bounty ZDF - Terra X , Germany 2007, 45 min.

- Explorers (Original: Ten Who Dared: The Explorers) - Mary Kingsley, Great Britain 1973, 45 min., 1976 in the First

Literature on Mary Kingsley (selection)

- Dea Birkett: Mary Kingsley: Imperial Adventuress . London: Macmillan 1992, ISBN 0-333-48920-9 .

- Katherine Frank: A Voyager Out. The Life of Mary Kingsley . London: Tauris 2005, ISBN 1-84511-020-X .

- Stephen Gwynn: The Life of Mary Kingsley . London: Macmillan 1932.

- Heather Lehr Wagner: Mary Kingsley: Exp O / T Congo . New York: Chelsea House Publishers 2013, ISBN 0-7910-7714-4 .

- Gero Brümmer: Mary Kingsley, "The Sea-Serpent of the Season" - self-perception and self-localization of a traveler to Africa. In: Helge Baumann, Michael Weise et al. (Eds.): Have you already flown tired? Travel and homecoming as cultural anthropological phenomena . Marburg 2010, ISBN 978-3-8288-2184-2 .

- Magdalena Köster: Mary Kingsley - What is life without a towel? In: S. Härtel, M. Köster: The journeys of women. Weinheim: Beltz & Gelberg 2003, ISBN 3-407-80915-8 .

- Bianca Walther: " I, as a Scientific Man" - Limits of Victorian femininity with Mary Kingsley, who is traveling to Africa . In: Uta Fenske, Daniel Groth, Matthias Weipert (eds.): Grenzgang - Grenzgängerinnen - Grenzgänger. Historical perspectives. Festschrift for Bärbel P. Kuhn on his 60th birthday. St. Ingbert: Röhrig 2017, pp. 103-114, ISBN 978-3-86110-635-7 .

Web links

- Literature by and about Mary Kingsley in the catalog of the German National Library

- Mary Kingsley. In: FemBio. Women's biography research (with references and citations).

Individual evidence

- ^ Katherine Frank: A Voyager Out. The Life of Mary Kingsley . London: Tauris Paperback 2005, p. 23 f.

- ↑ Frank 2005, pp. 28-36.

- Jump up ↑ Dea Birkett: Mary Kingsley: Imperial Adventures . London: Macmillan 1992, p. 12 f.

- ^ Mary Kingsley: Travels in West Africa . London: Virago 1982 [1897], p. 229 f.

- ↑ Birkett 1992, 130 ff.

- ↑ Kingsley 1982 [1897], p. 659.

- ↑ Birkett 1992, pp. 70 ff.

- ↑ Kingsley 1982 [1897], p. 659.

- ^ Bernard Porter: Critics of Empire. British Radical Attitudes to Colonialism in Africa 1895-1914 , London: Macmillan 1968, p. 256 ff.

- ↑ Tropical Fever - Risk in the Jungle. Mary Kingsley among Cannibals , accessed March 10, 2010.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Kingsley, Mary |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Kingsley, Mary Henrietta (full name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | British explorer, ethnologist, travel writer and lecturer |

| DATE OF BIRTH | October 13, 1862 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Islington |

| DATE OF DEATH | June 3, 1900 |

| Place of death | Simon's Town , South Africa |