Wounded Knee Massacre

The massacre of Wounded Knee (in the Lakota dialect: Chankpe Opi Wakpala ) took place on December 29, 1890 in the area of today's village of Wounded Knee in the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota . 300 defenseless members of various Sioux Indian tribes were murdered by members of the 7th US Cavalry Regiment . The massacre broke resistance from indigenous people in the Dakotas. It influences the culture and life of the reservation Indians to this day. Every year there is a 14-day memorial event that almost paralyzes life in the reservations. The march from Standing Rock to Pine Ridge is re-enacted by members of the tribes.

prehistory

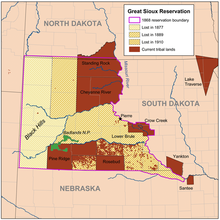

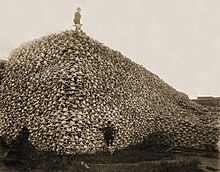

After the Great Sioux Reservation was smashed in 1889 and the bison were almost completely exterminated by white settlers, the Sioux Indians of the Dakotas were in a desperate situation. Their culture threatened to disappear. Once proud hunters had become supplicants dependent on food supplies from the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA). Their children were often sent to boarding schools far away from home, where speaking their language was forbidden. These schools were often run by Christian mission stations who tried to proselytize the Indians. The federal government also tried since 1870 to ban their rituals and dances. The nomads, who had no private land ownership, were to be turned into settled farmers. The Dawes Act 1887 in particular initiated this development.

On June 25, 1876, the Battle of Little Bighorn broke out , in which the 7th US Cavalry Regiment was almost completely destroyed by the Sioux and their allies. It was one of the last great Sioux victories. After the battle, thousands of additional soldiers banished the 25,000 Sioux to the reservation. Due to the construction of railroads, the discovery of gold in the Black Hills and white settlers, which led to the shrinking of the reserve and the elimination of the buffalo, they were no longer able to support themselves. The soils were also often too bad for growing food, and the Sioux traditionally had no connection with agriculture. 125 years earlier they had been driven from the fertile soils of Minnesota to the arid steppes of the Dakotas west of the Missouri , where they had lived as semi-sedentary hunters, gardeners and fishermen and embraced the prairie Indian culture. Now their culture should be radically changed again. Resistance arose under their spiritual leader, Sitting Bull .

In early 1890, the ghost dance movement reached the Dakotas. The ghost dance was one of many, ultimately unsuccessful, restoration efforts. The ghost dance spread rapidly over the areas of the former Great Sioux Reservation in April 1890. Pine Ridge in particular was a center of movement, but it also quickly found supporters in the Standing Rock Reservations and the Cheyenne River Reservations . It led to massive tensions within the tribes. Not everyone liked her. Indians in particular, employed by the Bureau of Indian Affairs or other United States agencies, saw the movement as more of a danger. Some of the residents had already adopted the Christian faith and were given areas for private cultivation. In Cheyenne River and Standing Rock in particular, there were conflicts between supporters of the dance and residents who tried to come to terms with the whites and defend their assigned private property. There was also a lot of money involved. Senator Henry L. Dawes had promised $ 1.25 an acre for the 35,000 km² that was to be ceded . Sitting Bull and his supporters were against it. They were also against farming because the soil was unsuitable for it: If the prairie grass disappeared, the winds could simply blow away the unprotected soil. The land was pasture, said Sitting Bull, and he was right. The Dust Bowl was the consequence of a wrong agricultural policy in the Dakotas. But most of the Sioux did not follow him, and the Indian agents tried everything to silence him.

Sitting Bull wasn't really a fan of ghost dance. He was a realist. But he did nothing about the movement, on the contrary: he invited preachers from Pine Ridge to teach his followers the dance. Opponents of the cession of land, the division of the reserve into individual parcels and the followers of the dance formed a group.

Escape of the fans of the ghost dance from Standing Rock

After Sitting Bull was murdered by his own tribesmen, many Lakota, including many ghost dancers, fled the Standing Rock reservation. Their destination was Pine Ridge, about 200 kilometers to the southwest. Chief Spotted Elk (in the Lakota dialect Unpan Glešká), mostly known in history as Big Foot, joined the fugitives with ghost dance fans from his group from the Cheyenne River Reservation. The Cheyenne River Reservation is south of Standing Rock. The chief was traveling in a covered wagon. He was seriously ill with pneumonia. The covered wagons carried white flags. The refugees attempted to reach the Pine Ridge Reservation in southwest South Dakota, the heart of the movement and the largest and most populous reservation in southern South Dakota. It was also called "the stronghold". They promised themselves protection from the Oglala -Sioux under Chief Red Cloud . They had to leave reservation areas because the reservation had been divided into seven smaller reservations in 1889 and an area outside the new reservations had to be crossed between the Cheyenne River and Pine Ridge. The US Army feared that fighting would flare up again after the Great Sioux Reservation was broken up. It declared all Indians found outside the reservations to be hostile. The army pursued the fugitives and placed them in the Bad Lands, an inhospitable wasteland north of the Pine Ridge Reservation, outside the reservation. The refugees were provided with food and taken to the Wounded Knee, a tributary of the White River about 20 kilometers northeast of the Oglala-Sioux camp and 8 kilometers from the Bad Lands, and within the Pine Ridge Reservation. There they set up camp and had to wait for the army command to decide what to do with their group.

massacre

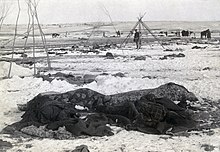

Colonel James William Forsyth had the order to deport the Sioux around Big Foot to a military camp in Omaha . The Sioux were first informed that they would have to hand over all firearms. Unsatisfied with the number of weapons they had volunteered, the soldiers began to search the tents. Forsyth was still unhappy with the result and ordered a body search . The Indians put up with this too - all except for the medicine man Yellowbird, who protested violently and danced a few steps of the ghost dance. Alarmed, the US soldiers continued to search. When they struck gold at Black Coyote, who had hidden a new Winchester under his clothes and refused to hand over the rifle - after all, he paid a lot of money for it, and the US soldiers would have taken the rifle away for good - it happened to a scramble in which a shot went off.

The US soldiers then began to fire. Shells fired from 42 mm Hotchkiss mountain cannons positioned on the hills killed numerous Indians. Chief Spotted Elk was among the dead. 25 cavalrymen also died, mostly killed by shells on their own side. After the massacre, an icy blizzard blew over the battlefield for 3 days. Most of the dead bodies froze and could not be recovered until the storm subsided. They were buried in mass graves at the Wounded Knee. Only a few members of Spotted Elk's group survived and were taken to the BIA's Pine Ridge Agency , where they were cared for at a Catholic mission station. There are contradicting information about the number of deaths. The number ranges from 150 to 300. Many saw the 7th Cavalry killings as an act of revenge for the lost battle of Little Bighorn 14 years before the massacre, when the unit was almost completely eliminated.

The day after the massacre, parts of the 7th US Cavalry Regiment found themselves in a difficult situation. They were involved in a battle by armed groups from neighboring Rosebud and had to be rescued from a critical situation by external forces (see Drexel Mission Fight ).

aftermath

The writer Lyman Frank Baum was probably not too far from public opinion of his time when he only complained about the dead US soldiers in the Aberdeen Saturday Pioneer of January 3, 1891, but called for their "total extinction" in relation to the conflict with the Indians:

“The curious policy of the government to use such a weak and wavering person as General Miles to monitor the troubled Indians has resulted in a terrible bloodshed among our soldiers (…) There has been ample time for swift and decisive action to prevent this disaster would have. (This newspaper) previously stated that our security depends on the total annihilation of the Indians. After having wronged them for centuries, let us follow up with yet another wrong and wipe these untamed and untamable creatures from the face of the earth (...) Otherwise, we can expect that the years to come will be as full of trouble with the redskins as they are the past. "

In the 20th century, the view of events changed. In particular, the 1970 non-fiction book Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee ( Bury my heart at the bend of the river ) by Dee Brown described the massacre as the culmination of the genocide of the Indian population of the Great Plains.

Medal of Honor controversy

Twenty members of the regiment received the Medal of Honor , the highest military award of the American government, for their involvement in the massacre . It is awarded for “striking bravery and fearlessness when life is in danger far beyond the fulfillment of duty in a battle against an enemy of the United States”. There are efforts on the part of the indigenous people to have these awards withdrawn.

music

In 1973 the rock group Redbone released their hit We Were All Wounded at Wounded Knee , some of the members of Redbone also had Indian ancestors. Buffy Sainte-Marie's album Coincidence and Likely Stories with the song Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee was released 19 years later . Furthermore, the American singer Dean Reed released a long-playing record in 1980 in the ČSSR , the GDR and the USSR , on which his title Wounded Knee In 73 appeared, in which he dealt with the events of 1973.

The American country singer Johnny Cash dealt with the fall of the Indian tribes in his album Bitter Tears . He processed the massacre at Wounded Knee and the death of Chief Big Foot in a song entitled Big Foot on his 1972 album America .

The German psychedelic rock band Gila released their last of three long-playing records in 1973 under the title Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee .

The German folk-rock band Ape, Beck & Brinkmann released a song on their LP Rainbowland in 1982 with the title Wounded Knee , in which they also referred to the living conditions of today's Indians.

British pop musician Nik Kershaw released a song entitled Wounded Knee on his album The Works in 1989 , which is about the changes in the lives of Indians. The reservations of the tribes and the injustice of the settlers and later US citizens are explicitly discussed.

Thobbe Englund and Nils Patrik Johansson wrote the Metal -Stück Wounded Knee , the 2017 Englund's solo album Sold My Soul was released.

See also

literature

- Heather Cox Richardson: Wounded Knee: Party Politics and the Road to an American Massacre . Basic Books, New York City 2010, ISBN 978-0-465-00921-3 .

- Mario Gonzalez, Elizabeth Cook-Lynn: The Politics of Hallowed Ground: Wounded Knee and the Struggle for Indian Sovereignty . University of Illinois Press, Urbana and Chicago 1999, ISBN 0-252-02354-4 .

- Dee Brown: Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee ( "Bury my heart at Wounded Knee"). Knaur Verlag, Munich 1972, ISBN 3-426-62804-X .

Web links

- http://www.indianerwww.de/ The Wounded Knee Massacre - December 29, 1890 (German)

- Spiegel massacre at the wounded knee blood stained the prairie (German)

- ARD Wounded Knee Hunger, Misery and Visions (German)

- www.history.com (English)

- The Wounded Knee Massacre. Primary Source Set Franky Abbott, Digital Public Library of America (English)

Individual evidence

- ^ Entry in the Yale University Library

- ↑ There are contradicting information in the literature on whether the Great Sioux was divided into six or seven reservations. There are researchers adding the Crow Creek Reservation (Fort Thompson) as the 7th reservation; others say Crow Creek was never part of the Great Sioux. The names of the other reserves are Pine Ridge, Rosebud, Standing Rock, Cheyenne River, Lower Brule, and Yankton.

- ↑ It has been estimated that nearly 300 of the original 350 men, women, and children in the camp were stain. Twenty-five soldiers were killed and thirty-nine wounded

- ↑ In the end, at least 150 Sioux were dead, according to other estimates up to 290. Spotted Elk, the 64-year-old leader, was one of the first to be shot at close range. The army left the corpses frozen in a three-day blizzard.

- ↑ Two weeks after the charismatic chief was assassinated, the US Army slaughtered more than 200 Lakota men, women and children at Wounded Knee. This massacre finally breaks the resistance of the Sioux

- ^ L. Frank Baum's Editorials on the Sioux Nation ( Memento of May 1, 2008 in the Internet Archive ); Northern State University, Aberdeen, South Dakota, USA