Standing Rock Reservation

The Standing Rock Reservation ( Lakota : Inyan Woslata ) is an Indian reservation in the US states of North Dakota and South Dakota . The reserve is the sixth largest in the United States of America at 9,251.2 square kilometers . According to a census in 2010, 8,250 people live permanently in the reserve. It covers the entire area of Sioux County in North Dakota and Corson County in South Dakota. To the south of this is the Cheyenne River Reservation , which is inhabited by Lakota Sioux Indians. Originally part of the Great Sioux Reservation , the Standing Rock Reservation was carved out by the US Congress in 1889 and has since been run as a separate reservation by the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA). The reserve administration is located in Fort Yates , North Dakota. The reservation is 85% populated by Dakota and Lakota Indians. The responsible agency of the BIA is also located in Fort Yates .

In 2016, the reservation gained worldwide attention due to ongoing protests against the Dakota Access Pipeline . The Cannon Ball district in the northeast of the reserve was particularly hard hit .

Surname

The name Standing Rock was coined by the Indian agent James McLaughlin , who visited the reservation for the first time in 1881 and became the head of the agency. It refers to a sacred stone that was originally located five miles (eight kilometers) north of what is now Fort Yates at the confluence of Porcupine Creek with the Missouri . McLaughlin arranged for the Yanktonai to move the stone to Fort Yates. They repositioned it on Proposal Hill north of the Indian Agency.

A legend about the stone: Around 1740 a Yanktonai Nakota man is said to have married a second wife, a Cheyenne . His first wife is said to have been an Arikaree . Due to the cultural and linguistic differences, the two women did not get along and the first woman became very angry. When the man's group left for a new camp, the first woman refused to follow them and stayed in the old camp with her baby. Only in the evening did the man notice that his first wife and baby were missing. He asked his brother to look for her. He found the woman and the baby, but they had turned into a stone.

administration

The Tribal Council of Standing Rock Sioux Tribe was formed under the tribal constitution passed on April 24, 1959. The tribal council has 17 members who are elected for four years each. The chairman ( chairman ), his deputy ( vice-chairman ) and his secretary ( secretary ) manage the business of the tribe and represent it externally. Eight members are elected from the respective districts of the reserve in which they must be resident. The remaining six just need to be members of the tribe. Council meetings take place on the first Tuesday, Wednesday and Thursday of each month. The chairman is David Archambault II (as of 2017). The eight counties on the reservation are Fort Yates, Porcupine, Kenel, Wakpala, Running Antelope, Bear Soldier, Rock Creek, and Cannonball.

population

The Standing Rock Sioux have between 13,893 to 15,797 registered tribal members, depending on the source. However, only an estimated 5,633 to 8,396 members - a good half at most - live in the reserve. According to the 2010 census, only around 69 percent of the 8,217 residents of the reservation were Sioux. Just over 21 percent were “white”; around 9 percent were Indians of other tribes. While the American population increased, the reservation population decreased between the 2000 and 2010 censuses. Around half of the residents (46%) are 24 years old or younger. On average, there are 4.6 people in each household on the Standing Rock Reservation (up from 3.27 in South and North Dakota and 3.8 in America).

education

According to census data, only around a third of the Native American population on the Standing Rock Reservation had a high school degree in 2000 , and less than two percent had a master's degree or doctorate . The reservation has had its own colleague in Fort Yates, Sitting Bull College, since 1973. Originally the colleague was called Standing Rock Community College . In 1996 it was renamed to its current name in honor of the great chief.

economy

The proportion of people with incomes below the poverty line is 41.15%, almost three times the national poverty rate of 13.8%. Half of children and adolescents under the age of 18 live in poverty (up from 21.9% in the US as a whole). The average household income in 2000 was in the reserve 21,625 dollars (for average 4.6 persons per household). The economic situation of the reserve is characterized by lower wages, less business activity and less money remaining in circulation than in comparable regions of both states outside the reserve. A lack of both jobs and affordable housing is causing young people in particular to migrate. A share of 59.3% of the jobs in the reserve are created with public funds and generate 88.3% of wages. Private companies are mainly active in education and social services (28.3%), in agriculture, forestry and mining (17.7%), and in the arts, entertainment, recreation, hospitality and restaurant industries (14.8%). The Standing Rock Sioux tribe operates 2 game casinos on their reservation area. One of them is located south of the Cannon Ball settlement in the district of the same name called Prairie Knights Casino & Resort in North Dakota. Another casino is located in South Dakota on the Grand River near Wakpala, called Grand River Casino & Resort . The casinos are an important economic factor for the reserve.

media

Together with the Cheyenne River Reservation , the Standing Rock Reservation operates its own radio station with the callsign KLND-FM .

history

The present reserve area was originally inhabited by Arikaree Indians. At the end of the 18th century and the beginning of the 19th century they were severely decimated by wars and smallpox epidemics and then settled in the northern area of today's Fort Berthold Reservation . The Lakota-Sioux immigrated from Minnesota to what is now the reserve area since 1776 , which was then claimed by the colonial power of France , but was sparsely populated. The culture and life of the Lakota changed, bison hunting became important, teepees replaced earth houses and horses began to play an important role in their culture.

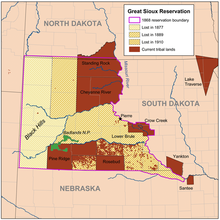

In 1803 the US government bought the territory from France as part of the Louisiana Purchase , but hardly allowed it to be settled because the Sioux were feared as warriors. In the Treaty of Fort Laramie in 1851 , the territories of the Great Sioux Nation were contractually established. The Heart River was determined as the northern limit . After the victory of the Lakota in the Red Cloud War (1866–1868), the Great Sioux Reservation as a permanent settlement area and extensive hunting and fishing rights in neighboring areas were guaranteed to them in the Treaty of Fort Laramie in 1868 . The treaty designated the entire present-day US state of South Dakota west of the Missouri, including the Black Hills (from the northern border in Nebraska to the 46th parallel and from Missouri in the east to the 104th longitude in the west) as Indian land unrestricted and unmolested use and settlement by the Sioux. The Sioux also received hunting rights in other areas, north and west of the reservation in what is now Wyoming , Montana and Nebraska. The Bureau of Indian Affairs set up several Indian agencies on the reservation, including what is now the Standing Rock Agency . In 1875 the agency's area was expanded. Instead of the 46th parallel, the Cannonball River now formed the new northern border.

Originally the Great Sioux Reservation belonging to Black Hills are the Lakota -Sioux as sacred mountains . They are also the subject of numerous Lakota myths. Tribesmen still visit the spiritual places in the mountains to practice their religion. An expedition under George Armstrong Custer, illegal under the Treaty, explored the Black Hills in 1874 and found gold in the mountains . Gold seekers illegally entered the area, a gold rush developed and conflicts arose between the gold seekers and the Lakota. After the defeat in the Battle of Little Bighorn in 1876 and another defeat, the US government legally withdrew the Black Hills from the Sioux in 1877. She broke the Treaty of Fort Laramie in 1868, which had required the consent of three-quarters of the male residents to assignments. As a result, the Standing Rock Reservation Government does not recognize the 1877 Act to this day.

The United States Congress divided the Great Sioux Reservation into parcels with the Dawes Act 1887 and then into separate reservations with another law on March 2, 1889, the current Standing Rock Reservation and five other reservations (Cheyenne River, Pine Ridge, Rosebud, Lower Brule, and Crow Creek), reducing the total Native American land by eleven million acres . The residents only reluctantly and under great pressure agreed to the division. Approximately 50% of the male residents of Standing Rock agreed to the division into multiple reservations. Unlike other reserves, Standing Rock kept its borders afterwards, but lost more land in the 1960s when the dam was built on what is now Lake Oahe .

In 1890 the reserve became known as the center of the ghost dance movement . James McLaughlin, the manager of the reservation, had long regarded the ghost dancers with suspicion and feared a riot. President Benjamin Harrison ordered an army investigation and restricted food rations for uncooperative Indians, adding to tensions. On December 15, 1890, the leader of the movement, Chief Sitting Bull , and 14 other reservation residents, including children, were shot dead by US soldiers. Many Sioux, including Chief Spotted Elk (Big Foot), fled to the Badlands . The US Army tracked them down and captured them to be transferred to the Pine Ridge Reservation . On December 29, 1890, there was the Wounded Knee massacre of 150 to 290 men, women and children from the reservation and the Cheyenne River reservation to the south. Spotted Elk was shot dead at close range.

Since the 1930s the reserve government has tried to get back the areas lost in 1877 and 1889 by legal means. She joined the United States v. Sioux Nation of Indians . The case was ruled by the United States Supreme Court on June 30, 1980. The Supreme Court ruled that Standing Rock residents should be immediately paid monetary compensation for the loss of their lands, including lost interest. However, the Sioux refuse to accept the money to this day. They want their country back.

The reservation has only been visited by two US presidents : in 1936 by Franklin D. Roosevelt , on June 13, 2014 by Barack Obama .

Oahe dam

After several years of planning and preparation without the involvement of Indian representatives, the US Congress passed a Flood Control Act at the end of 1944 and put into effect the Pick-Sloan Plan , which provided for the construction of dams along the Missouri River - including the Oahe Dam whose reservoir was to flood large parts of the Standing Rock Reserve. After the tribe successfully opposed the seizure of their land for the proposed reservoir, Congress passed the Standing Rock Land Taking Act in September 1958 . This law provided for the removal of approximately 56,000 acres of reservation land and compensation payments totaling $ 12.3 million. The dam was put into operation in 1962. Through its 250-mile-long reservoir Lake Oahe the two reserves lost Standing Rock and Cheyenne River 68 percent of their pastures. Around 37 percent of Indian families had to resettle. It was the largest loss of Indian land to public works in US history. The reserve's economy has not recovered from this to this day. The compensation was far too low and just covered the moving costs. But the culture of the Indians was also badly affected. Before the dam project they led a somewhat autonomous life and were able to feed and support themselves through agriculture, but after the construction of the dam they became dependent on public aid. The current resistance against the oil pipeline on the Cannonball River takes place against this historical background.

Oil line Dakota Access Pipeline

As of April 2016, the reservation government and the tribe led protests against the Dakota Access Pipeline underground petroleum pipeline . This led to the largest Indian protest in America since a violent confrontation in Wounded Knee in 1973 .

The pipeline is to be laid near Cannonball Creek under the Missouri and, according to the reservation government, will only run 500 meters past the reservation boundary. According to the Treaty of Fort Laramie in 1851 , the pipeline is located in the Great Sioux Nation area . The 1868 Treaty of Laramie designated the area of what is now the Pipeline Route as the exclusive hunting area of the Great Sioux Reservation as long as there was enough buffalo to hunt but not as a settlement area. Due to the extermination of the buffalo, the area claim was dropped. The treaty of 1875 established the current boundary of the settlement area. The tribe complains that the construction work would destroy important Sioux tombs. The Sioux fear that the oil pipeline planned by the Energy Transfer company could contaminate the water of the reserve and make the area uninhabitable in the event of a pipe burst. The relocation of the planned pipeline route into Indian territory due to resistance elsewhere is referred to as "environmental racism" in the reservation. The protest was joined by members of around 200 Native American and Canadian tribes, as well as numerous non-Indian supporters. At times, up to 5,000 people lived in the Oceti Sakowin ("Seven Fires") protest camp , which was set up in April 2016 near the Missouri.

The police in Morton County , north of Standing Rock, used water cannons at sub-zero temperatures and rubber bullets against demonstrators in November 2016 . With a video linked to Facebook, the sheriff's office in charge tried to justify the police's action and stated that the video showed demonstrators who were prepared to use violence. The commentators of the New York Times, however, saw in it “ an imbalance of power, where law enforcement fiercely defends property rights against protesters' claims of environmental protection and the rights of indigenous people ” (German: “an imbalance of power in which the executive is violent Property rights defended against protesters' demands for environmental protection and the rights of indigenous people. ")

On the weekend before the expiry of the eviction period for the protest camp, over 2000 veterans came to support the protests as human shields. Led by Wesley Clark Jr, son of General Wesley Clark , several hundred veterans at the protest camp also asked for forgiveness for injustices committed by soldiers in the course of history.

On December 5, the Department of Civil Affairs and the US Army Corps of Engineers , which owns the land to be cultivated, announced that construction of the controversial oil pipeline would be halted. The planned route is not approved, alternative routes should be checked. Thousands of protesters stayed in the camp. For security reasons, the reservation government asked several times for the protest camp to be closed and distanced itself from violations of the law by demonstrators.

On January 24, 2017, four days after taking office, US President Donald Trump lifted the construction freeze with an executive order and instructed the US Army Corps of Engineers to approve the construction project in an urgent procedure. He also lifted some requirements for environmental impact assessments, ordered only steel from US companies to be used for further construction, and announced that the US government's contracts with the companies involved in the construction would be renegotiated. The Indian tribe announced legal action against Trump's decision.

Not all reservation residents agreed to the protest camps. Especially in the affected district of the Cannon Ball reservation , many residents were not enthusiastic about these camps. The peaceful life of the residents would be endangered by the demonstrations. The residents would have to take long detours because roadblocks would block direct routes. Ambulances would have to take a 80-kilometer detour. Access to the Prairie Nights Casino , the largest employer in the district, would also be blocked. In addition, the camps would be in flood areas. Cannon Ball residents feared that the waste from the camps could be washed into Lake Oahe. The camps would also pose a challenge to the security forces and the reservation infrastructure. The competent council of Cannon Ball Robert Fool Bear Sr. asked the chairman of the council Dave Archambault II to have the protest camps cleared, if necessary with the help of the FBI . On January 20, 2017, the Standing Rock Sioux Tribal Council supported a resolution introduced by the Cannon Ball District to close the camps until the end of February.

The government's new eviction period for the protest camp was the end of February. Construction work was resumed immediately. The Cheyenne River Sioux requested a construction freeze while a previously filed lawsuit by the Standing Rock Sioux was still being processed. Numerous Indian tribes reunited for demonstrations against the oil pipeline.

literature

- Donovin Arleigh Sprague: Standing Rock Sioux , 2004, ISBN 0-7385-3242-8 .

- Michael L. Lawson: Dammed Indians: The Pick-Sloan Plan and the Missouri River Sioux, 1944-1980 . University of Oklahoma Press, 1994, ISBN 0-8061-2672-8 .

Web links

- Official website of the reserve (English)

- Official website of the protest camp run by the reserve administration

- Official website of the Standing Rock Agency of the BIA (English)

- The History and Culture of the Standing Rock Oyate (English)

- Grand River Casino & Resort (English)

- Prairie Knights Casino & Resort (English)

Reservation Treaties and Laws:

- Treaty of Fort Laramie 1868 on PBC television website

- Boundary established in 1877: Chapter 72 Feb. 28, 1877 (English). In: Charles J. Kappler: Indian Affairs: Laws and Treaties. Vol. I, Laws . Government Printing Office, 1904

- Boundary established in 1889: Sioux Act of 1889 (English). In: Charles J. Kappler: Indian Affairs: Laws and Treaties. Vol. I, Laws . Government Printing Office, 1904

- Standing Rock Land Taking Act , September 3, 1958

Individual evidence

- ↑ Standing Rock Reservation ( English ) In: Geographic Names Information System . United States Geological Survey . Retrieved April 30, 2016.

- ↑ Donovin Arleigh Sprague: Standing Rock Sioux. Arcadia, Charleston, SC 2004. ISBN 0-7385-3242-8 ( books.google.de ).

- ↑ Inyan = stone, boulder, Woslata = upright, sharp upwards.

- ^ Prologue to Lewis and Clark: The Mackay and Evans Expedition by W. Raymond Wood University of Oklahoma Press, page 107

- ↑ James H. Howard: Yanktonai ethnohistory: And the John K. Bear winter count . Plain Anthropologist Corp. 1976

- ↑ a b Website of the reserve: History ( Memento of the original from June 10, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. . Retrieved March 18, 2017

- ↑ Reservation website: Tribal Council ( Memento of the original from November 23, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. . Retrieved March 18, 2017

- ↑ North Dakota Studies: Population ( Memento of the original from March 21, 2017 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. . Retrieved March 19, 2017

- ^ A b c South Dakota Department of Tribal Relations: Standing Rock Indian Reservation . ( Memento of the original from May 14, 2017 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Retrieved March 18, 2017

- ↑ a b c d Standing Rock Sioux Tribe: Comprehensive Economic Development Strategy 2013-2017 . ( Memento of the original from March 9, 2017 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Retrieved March 18, 2017

- ↑ North Dakota Studies: Infrastructure and Services ( Memento of the original from March 20, 2017 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. . Retrieved March 19, 2017

- ^ The History of Sitting Bull College

- ↑ standingrock.org ( Memento of the original from March 5, 2017 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. The Standing Rock Sioux Tribe has two casinos located near Cannon Ball, North Dakota, and the Grand River Casino near Wakpala, South Dakota.

- ↑ Cynthia Littleton: South Dakota Radio Station to Broadcast Standing Rock Benefit Concert With Jackson Browne, Bonnie Raitt . In: Variety , November 23, 2016

- ^ History of South Dakota Herbert S. Schell, 2004, South Dakota State Historical Society Press, ISBN 0-9715171-3-4

- ↑ Bureau of Indian Affairs : Standing Rock Agency ( Memento of the original dated November 13, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. . Retrieved March 18, 2017

- ^ Gail Evans-Hatch: Centuries Along The Upper Niobrara , 2008. In: NPS History Electronic Library. Retrieved March 18, 2017

- ↑ Timeline: Black Hills Expedition of 1874. In: Public Broadcasting Service . Retrieved March 16, 2017 .

- ↑ a b Broken Promises: Standing Rock Sioux Tribe Cites History of Government Betrayal in Pipeline Fight. In: ABCNews , November 22, 2016.

- ↑ a b Timothy J. Kloberdanz: In The Land of th [e] Indian Woslata: Plains Indian Influences on Reservation Whites. In: Great Plains Quarterly. No. 323, 1987.

- ^ North Dakota Studies: Lesson 4: Alliances And Conflicts. Topic 2: Sitting Bull's People. Section 7: The Ghost Dance. Retrieved March 18, 2017.

- ^ Massacre at the Wounded Knee. Blood stained the prairie. In: Der Spiegel. December 29, 2015.

- ↑ caselaw.findlaw.com: United States Supreme Court UNITED STATES v. SIOUX NATION OF INDIANS. 1980, numbers 79-639. Negotiated on March 24, 1980, decided on June 30, 1980.

- ↑ Why the Sioux Are Refusing $ 1.3 Billion www.pbs.org.

- ↑ Pow-Wow with the President. In: Der Spiegel. On-line.

- ^ Paul A. Olson: The Struggle for the Land: Indigenous Insight and Industrial Empire in the Semiarid World. University of Nebraska / Center for Great Plains Studies, 1990, ISBN 0-8032-3555-0 ( books.google.de ).

- ↑ Michael L. Lawson: Dammed Indians: The Pick-Sloan Plan and the Missouri River Sioux, 1944-1980 . University of Oklahoma Press, Norman 1994, ISBN 0-8061-2672-8 ( books.google.de ).

- ^ Robert Kelley Schneiders: Flooding The Missouri Valley The Politics Of Dam Site Selection And Design. In: Great Plains Quarterly 17, 1997. pp. 237-491.

- ^ Harriett Skye: Mini Nataka Pi: The Oahe Dam and the Standing Rock People, 1900-1960. Berkeley 2007, ISBN 978-0-549-52831-9 .

- ↑ Peter Capossela: Impacts of Army Corps of Engineers Pick Sloan Program on Indian Tribes. ( Full text ) In: Journal of Environmental Law and Litigation. Volume 30, No. 1, May 2015.

- ↑ 7 history lessons that help explain the Dakota Access Pipeline protests. In: USA Today . November 16, 2016.

- ↑ a b Berliner Morgenpost : Standing Rock's resistance ends - oil pipeline is being built , February 24, 2017.

- ^ Energy Transfer website: Dakota Access, LLC . As of December 2016.

- ↑ Violent protest against the pipeline - Spiegel Online, September 4, 2016.

- ↑ Standing Rock protests: this is only the beginning. In: The Guardian . September 12, 2016.

- ↑ a b Bayerischer Rundfunk : A pipeline and civil rights , December 14, 2016.

- ↑ The New Yorker : Holy Rage: Lessons from Standing Rock , December 22, 2016.

- ^ Power Imbalance at the Pipeline Protest. In: The New York Times . November 26, 2016. Retrieved November 26, 2016 .

- ^ New York Magazine : Thousands of Veterans to Form a Human Shield Around Standing Rock Protestors , December 1, 2016

- ^ Veterans at Standing Rock ask Native Americans for forgiveness . In: USA Today , December 6, 2016. Retrieved December 14, 2016.

- ↑ Die Zeit : US Army stops controversial pipeline construction , December 4, 2016; Der Spiegel : Construction of the controversial oil pipeline in North Dakota stopped. , December 5, 2016.

- ↑ Standing Rock Sioux chairman accuses activists of jeopardizing protest of Dakota Access pipeline. In: Washington Times , February 2, 2017

- ^ Standing Rock chairman looks to history as divisions emerge among activists. In: The Guardian . February 13, 2017.

- ↑ CNBC : Trump ignores question about Standing Rock Sioux after signing Dakota Access order. January 24, 2017.

- ↑ Alexander C. Kaufman: Trump Signs Executive Orders On Keystone XL, Dakota Access Pipelines . In: Huffington Post . January 24, 2017.

- ↑ Der Tagesspiegel : Donald Trump. The silent world war against the Indians. January 25, 2017.

- ^ The Guardian : Standing Rock Sioux tribe says Trump is breaking law with Dakota Access order , Jan. 26, 2017

- ↑ cnn.com Not all the Standing Rock Sioux are protesting the pipeline.

- ↑ reuters.com Clean-up begins at Dakota pipeline protest camp.

- ↑ www.dailykos.com Standing Rock Sioux Tribal Council Urges Shutdown of All Protest Camps Near the Cannonball District.

- ^ Bismarcktribune.com Tribal council supports asking protesters to leave Cannon Ball.

- ↑ Die Zeit : Sioux tribe wants to stop pipeline construction in court , February 10, 2017.

- ↑ Berliner Morgenpost : Standing Rock: Indian protest against oil pipeline - a chronicle , February 22, 2017.

- ↑ Tagesschau : Demo against oil pipeline Indians united against Trump , March 11, 2017.