Nea Ekklēsia

The Nea Ekklēsia ( Greek Νέα Ἐκκλησία , dt. New Church ) was a Byzantine church that Emperor Basil I had built in Constantinople between 876 and 880 . The church was the first monumental church building in the city after Hagia Sophia in the 6th century and marked the beginning of the middle epoch of Byzantine architecture . The church was used as a church until the Ottoman conquest of Constantinople in 1453 . The Ottomans then used the building as a powder magazine. In 1490 the Nea Ekklēsia was destroyed in a lightning strike.

history

Emperor Basil I founded the Macedonian dynasty in 867 , which ruled Byzantium until 1056. Basil saw himself as the restorer of the empire and as the new Justinian . He initiated an ambitious building program in Constantinople based on the model of his predecessor. The Nea Ekklēsia was to be Basil's Hagia Sophia and with its name a symbol of a new era.

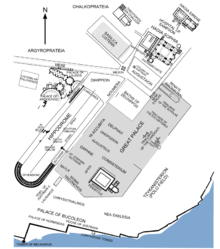

The church was built under the personal supervision of Basil. The Nea Ekklēsia was built at the southeast end of the Great Palace of Constantinople , near the no longer existing Tzykanistērion (field for a game similar to polo). Not far away, Basil also built the Pharos Palace Chapel . The Nea Ekklēsia was consecrated on May 1, 880 by the patriarch Photios I and was under the patronage of Christ, the Archangel Michael (in later sources Gabriel ), the prophet Elijah (one of Basil's favorite saints), the Virgin Mary and the St. Nicholas of Myra . It is indicative of Basil's intentions that he furnished the new church with its own administration and assets based on the model of Hagia Sophia. During his reign and that of his direct successors, the Nea Ekklēsia played a major role in the palace celebrations.

In the late 11th century the church became part of the New Monastery ( Greek Νέα Μονή ). Emperor Isaac II robbed the church of its decorations, furniture and liturgical objects and used them to restore the church of St. Michael in Anaplous (today Arnavutköy). The building was used by the Latins in the Latin Empire and under the Palaiologists in the restored Byzantine dynasty . After Constantinople was conquered by the Ottomans in 1453, a powder store was located here. When the building was struck by lightning in 1490, it was completely destroyed and then demolished. As a result, there is little information on the building and few literary reports are available. First and foremost, the Vita Basilii should be mentioned here. The approximate location is known from early maps.

architecture

Little is known about the architectural details of the church. The church had five domes: the central dome was dedicated to Christ, the four smaller ones were chapels dedicated to the four saints of the church. The exact design of the domes is unclear. Most scientists assume that the building was a cross-domed church - similar to the Myrelaion - and the Lips monastery church . In fact, the type of structure widely used in the Orthodox world from the Balkans to Russia is attributed to the importance of Nea Ekklēsia.

The construction of the church was the crowning element of Basil's building program and the emperor spared no expense to have the church richly furnished. Other churches and buildings in the city, including the mausoleum of Justinian, were stripped of their jewelry and the imperial navy was assigned to transport marble, with the result that the Byzantine province of Syracuse in Sicily fell to the Arabs in 877/78 .

Basil's grandson, Emperor Constantine VII, described the decor of the church in De cerimoniis

“This church, adorned like a bride with pearls and gold, with a variety of colored marbles, with mosaics and textiles made of silk, he [Basil] serves Christ to the immortal bridegroom. Its roof, consisting of five domes, shimmers golden and shines with beautiful images such as stars, while the exterior is adorned with brass that resembles gold. The walls were embellished with precious marble of many colors, while the chancel was decorated with gold and silver, precious stones and pearls. The templon that separates the chancel from the nave, its columns that support a lintel , the steps in front of it and the altars themselves are made of silver, flooded with gold, precious stones and precious pearls. The floors are covered with silk carpets that seem to come from Sidon ; it has been adorned to a large extent with marble slabs of different colors ( opus sectile ), which are surrounded by mosaic bands with different themes, which are all interconnected and have a great elegance. "

The atrium of the church faced the western entrance and was decorated with two marble and porphyry fountains . Two porticos ran along the north and south façades to the Tzykanistērion and on the south side a treasury and a sacristy were added. To the east of the complex was a garden ( Mesokēpion ; Eng . Middle garden).

Relics

In addition to the Church of St. Stephen in the Daphne Palace and the Pharos Palace Chapel, the Nea Ekklēsia was the most important repository for relics in the imperial palace. These included the sheepskin cloak of the prophet Elijah , the table of Abraham at which he entertained three angels, the horn that the prophet Samuel used to anoint David , and relics of Constantine the Great . After the 10th century, many relics were moved from here to other parts of the palace, including the staff of Moses from Chrysotriclinus .

literature

- Paul Magdalino : Observations on the Nea Ekklesia of Basil I . In: Yearbook of Austrian Byzantine Studies 37, 1987, pp. 51–64.

- Cyril Mango : The Art of the Byzantine Empire 312-1453. Sources and Documents . University of Toronto Press, Toronto 1986, ISBN 978-0-8020-6627-5 .

- Cyril Mango: Nea Ekklesia . In: Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium , 1991, p. 1446.

- Holger A. Klein : Sacred Relics and Imperial Ceremonies at the Great Palace of Constantinople . In: Franz Alto Bauer (ed.): Visualizations of rule. Early Medieval Residences - Form and Ceremonial (= Byzaz Volume 5). Istanbul 2006, pp. 79-99 ( digitized version ).

- Robert Ousterhout : Reconstructing ninth-century Constantinople . In: Leslie Brubaker (Ed.): Byzantium in the ninth century: dead or alive? Papers from the thirtieth spring symposium of Byzantine studies. Birmingham March 1996 . Ashgate, Aldershot 1998, pp. 115-130 ( digitized ).

Web links

- Nebojsa Stankovic: Nea Ekklesia . In: Constantinople (= Encyclopaedia of the Hellenic World , Volume 3), Foundation of the Hellenistic World, Athens 2008 ( digitized version )

- Reconstruction of the New Ekklesia , Byzantium 1200 project

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Stankovic (2008)

- ↑ Mango (1986), p. 194; Magdalino (1987), p. 51.

- ↑ a b c Mango (1991), p. 1446.

- ↑ Mango (1986), p. 194; Robert Ousterhout: Master Builders of Byzantium . Princeton University Press, Princeton 1999, ISBN 0-691-00535-4 , p. 34.

- ↑ Magdalino (1987), pp. 61-63.

- ↑ Mango (1986), p. 237.

- ^ Robert Ousterhout: Master Builders of Byzantium . Princeton University Press, Princeton 1999, ISBN 0-691-00535-4 , p. 140.

- ^ Robert Ousterhout: Master Builders of Byzantium . Princeton University Press, Princeton 1999, ISBN 0-691-00535-4 , p. 36.

- ^ Cyril Mango: Byzantine architecture . New York 1976, ISBN 0-8109-1004-7 , p. 196.

- ↑ a b Mango (1986), p. 181.

- ^ Warren Treadgold : Byzantium and Its Army, 284-1081 . Stanford University Press, 1995, ISBN 0-8047-3163-2 , p. 33.

- ^ Robert Ousterhout: Master Builders of Byzantium . Princeton University Press, Princeton 1999, ISBN 0-691-00535-4 , pp. 34-35 (English translation).

- ↑ Mango (1986), pp. 194-196.

- ↑ Klein (2006), p. 93.

- ↑ 2 Kings 2.7–14 EU

- ↑ Gen 18: 1-8 EU

- ↑ 1 Sam 16.13 EU

- ↑ Klein (2006), pp. 92-93.