Opium den

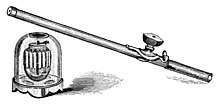

An opium den , also called opium divan , (English: Opium den ) describes a smoking parlor in which opium was sold and smoked legally with a license or illegally without a license. Starting in China , opium dens also arose in Southeast Asia, North America and in the port cities of Western Europe in the 19th century. Depending on the clientele, the opium dens were simply or sumptuously furnished. As a rule, the opium dens consisted of a large room that essentially contained bunks for the opium smokers, but in individual cases there were also opium dens with a large number of individual opium divans starting from a corridor. Most establishments had extensive equipment, such as B. special opium pipes and opium lamps, which were necessary for smoking opium. The smoking of the opium usually followed a meticulously prescribed ceremony. One hour before the opium smoking, the rooms of the opium divan were prepared accordingly, for example by tidying up the consumption room and providing the equipment required for smoking. Smoking should only take place in a community and conversations should also be stopped after smoking opium has started. As a rule, 20 to 40 pipes a day were consumed. Chinese people who smoked 80 to 100 opium pipes a day were respectfully referred to as "big smokers".

“The opium smoker, who always lay down comfortably on his side, took the pipe in one hand and then used a fine needle to stick a pea-sized Chandu lump in his can with the other . He held this over the flame of his small lamp until the Chandu had changed its initially liquid form and had thickened to a tough pitch. Then the smoker pushed it into the narrow opening of his pipe bowl. With a twisting motion he pulled the needle out, creating a tiny channel to the bamboo tube. Now he could make himself comfortable; he rested on his side, turned the bowl of the pipe down and held it over the flame. He only took a few puffs and kept the smoke down as long as possible. Depending on how they got used to it, that peculiar state of comfort over the smokers soon came, sometimes even after several pipes. The drug of the rapture had its effect, the heaviness was lifted, and pleasant ideas, often of an erotic nature, filled him. This was followed by leaden fatigue and finally a narcotic sleep. The hangover came after waking up and with it the insurmountable desire for the next pipe. "

The Origin, Establishment and Decline of Opium Smoking in China

In China, opium has long been consumed in solid form or dissolved in water, juices and wine. Traditional consumption patterns changed through the custom of tobacco smoking. Due to long-distance trade with Portugal and Holland , tobacco consumption spread from Formosa (Taiwan) to the southern mainland provinces of China. Even the ban imposed by the last Ming emperor in 1644 - anyone who traded tobacco with the “barbarians” was threatened with beheading - could not curb tobacco consumption. At the beginning of the 17th century, the Dutch brought the custom of smoking opium to Formosa . Since tobacco consumption was forbidden and the drug was highly taxed, the tobacco-addicted Chinese subjects began to add opium to the tobacco and smoke it. Finally, the opium, in the fermented form of Chandoo , was smoked pure. Opium divans appeared everywhere, in which one could buy and enjoy opium. Wealthy Chinese had their own smoking parlor in their property, where opium was smoked with business friends. Poor Chinese visited Spartan opium dens. This development was viewed with suspicion on the part of the Chinese ruling family, as smoking was not yet acculturated at that time and reports of excessive intoxication and deaths raised concerns that this form of consumption could have an adverse influence on general mores.

Concerned about the widespread use of opium smoking throughout the country, the Chinese Emperor Yongzheng issued an anti-opium edict in 1729, which made buying opium and operating opium divans a heavy penalty. Despite numerous other imperial anti-opium edicts in the following decades, the spread of opium consumption in Chinese society could not be prevented. In China in particular, the opium was not only smoked for relaxation, but also because of its appetite-suppressing effect, as at that time there were periodic famine in China. By 1830, the total number of opium addicts in China was already estimated at two million people, so the Chinese Emperor Daoguang took drastic measures against the British East India Company's illegal opium trade in 1839 . After China's defeats in the First (1839–1842) and Second Opium War (1856–1860), the opium trade was legalized in China. The number of opium addicts rose from 13 million in 1906 to 40 million in 1945. Only after Mao Zedong came to power in 1949 did the number of opium smokers in China fall rapidly and steadily.

Opium dens in North America

In the United States , opium smoking was essentially practiced in San Francisco , New York City , New Orleans, and Albany . The opium dens in New York's Chinatown were not as opulent and numerous as those on the American west coast. HH Kane, who studied opium use in New York between 1870 and 1880, located the opium dens, or "opium joints" in contemporary usage, between Mott Street and Pell Street in Manhattan's Chinatown. At that time, the opium dens in New York were operated almost entirely by Chinese. As in San Francisco, the opium dens in New York were used by Americans of various origins. An estimated 100,000 to 150,000 users in the United States are believed to have smoked opium regularly at the beginning of the 20th century. The Chanduimport rose on an annual average from 10,000 kg in 1860–1869 to 75,000 kg in the years 1900–1909, while the total population of the USA only increased by two and a half times and the proportion of the Chinese population only doubled. In February 1909, the import of smoked opium was made a criminal offense in the USA. This law, which was largely shaped by the doctor Hamilton Wright, was intended to send a signal to the International Opium Commission . The international opium conference in 1912 finally resulted in an international ban on opium. In addition, by law in 1914, domestic chandu production was considerably restricted and finally banned, so that as a result, illegal domestic chandu production was temporarily established and opium smuggling increased considerably. Even after the First World War , 700 opium smokers are said to have been arrested in New York within two and a half years. The last opium den in New York wasn't closed until the 1950s.

In Canada , Chinese immigrants created Chinatowns in Victoria and Vancouver . As a result, opium dens were established in these cities towards the end of the 19th century. "Shanghai Alley" in Vancouver became famous for its rustic opium dens. As elsewhere, the Canadian opium dens were visited by both Chinese and non-Chinese. After the US city of San Francisco levied taxes on smoked opium, trade shifted to Vancouver. A significant part of the smoked opium was smuggled into the USA from there.

Opium smoking as the stigma of Chinese immigrants in San Francisco

Even before the first Chinese in the United States migrated, was, by reports of US spies and missionaries who visited the "land of darkness" since 1800 the image of gambling addicts, opium smoking Kuli coined. Over 100,000 Chinese immigrants came to the United States between 1850 and 1890 alone; it was not uncommon for them to be recruited as cheap labor through American brokerage offices in China. The “Pacific Railroad of California” also recruited numerous Chinese workers for railroad construction in California. Many local workers left their jobs during the gold rush, and the Chinese were welcome replacements.

“The skinny strangers, suspected at first, turned out to be persevering workers who, despite the brutal working conditions - hundreds perished in the explosions, which were carried out almost without protective measures - tolerated their work. Even after work it was quiet in the workers' camps, the alcohol-abstinent Chinese smoked their opium pipes and no one was offended. On the contrary, some of their wages were sometimes even paid in the form of opium ”.

Until the transcontinental railroad was completed in 1869, there was only latent anti-Chinese resentment, which was fueled by racist campaigns in the period that followed. Several 10,000 job-seeking Chinese moved to the greater San Francisco area, where they were soon seen by the local workforce as annoying competition: They were more willing to toil under much tougher working and wage conditions than the whites. During the economic crisis of the 1870s, the Chinese finally made up 25% of the wage labor force in California . In particular, the unions agitated against the undesirable “Chinese wage pressers”. Not only were the Chinese denied union membership, but they were also implicated in deliberately undermining the American economy in order to dominate it afterwards. At the center of anti-Chinese resentment came the custom of smoking opium, which was used as evidence of the “dangerousness” of the Chinese. This resentment was nourished by the tabloid press, in which the Chinese were generally described as dirty and obscure characters, who were trusted to carry out every conceivable kind of crime, from assassination to prostitution. The corresponding pamphlets were then illustrated with pictures of opium smokers, which were intended to show the readership the depravity of the “Chinese race”. When white Americans also adopted the opium smoking habit after 1870, the foundations of white America were seen threatened. In the "Asiatic Exclusion League", for example, the following could be heard:

“Somehow, they were tricked into using the drug by the Chinese. There have been times when little girls no more than 12 years old were found in Chinese laundries while under the influence of the drug. What other crimes were committed in these dark and smelly places when the young, innocent victims were under the influence of the drug is almost too horrific to imagine. "

These and other reports worried authorities and lawmakers, with the consequence that they now deal with the "Chinese question". Numerous anti-Chinese laws were passed in quick succession, which considerably impaired and increasingly restricted their culture and living conditions (e.g. ban on traditional hairstyle in 1873, immigration restrictions, only taking up residence in certain parts of San Francisco in 1865). The first criminal law of the western world against opium consumption ("City Ordinance"), which was enacted in San Francisco in 1875 and banned opium smoking in the event of fines and / or imprisonment, also joined the series of these discriminatory laws. This law was promptly implemented, with arrests and convictions. With an estimated 3000-4000 "opium addicts" in San Francisco in 1885, there were 38 arrests of owners of the smoke houses and 220 arrests of visitors to these establishments. Since the ban did not have the desired effect, legalization of opium smoking was considered at times in order to participate in potential taxes. However, this idea was discarded in favor of maintaining the strategy of criminalization. However, opium smoking could not be eradicated; it would only gradually disappear until 50 years later. This law was tightened considerably in 1889: Opium smoking and operating a dens could be punished with a US $ 250 to US $ 1000 fine and / or three to six months' imprisonment. Most other American states also passed laws against opium smoking and opium dens by 1914. In addition, the Chinese were no longer allowed to import smoked opium from 1887 onwards; a law passed in 1890 meant that production was only restricted to US citizens. The anti-Chinese laws formed the prelude to a veritable smear campaign that, in addition to various injustices, even led to pogroms in Los Angeles and San Francisco. The white opium consumption (oral or subcutaneous) was hardly affected by the smoking opium ban; this ban was clearly directed against a minority, whose status was symbolically degraded and criminalized. It served the public affirmation of white norms and their predominant conception of morality.

Opium dens in Europe

Opium smoking also became fashionable in Western Europe during the 19th century. Opium dens, which were mainly operated by the Chinese, established themselves in the port cities in particular. The visitors consisted of Chinese and Europeans. Opium dens existed in London , Marseille and Le Havre as early as 1840 . French emigrants introduced the custom of opium smoking from Indochina to France . Later, for example, opium caves also existed in Rotterdam , Paris , Toulon , Brest , Liverpool and Hamburg . Poor industrial workers and dock workers in particular visited the smoking salons, but also protagonists of the intellectual and artistic scene. In 1921, 184 people were prosecuted for opium smoking in England, 69 of them in London and 72 in Liverpool. Of these 184 people, 92 were seafarers. In contrast to North America, however, there were only small Chinese communities in Europe, so the opium dens there remained only a marginal phenomenon.

Opium dens in Hamburg

In Hamburg in 1910 the number of Chinese registered in the city was 207 people, which fell briefly after the end of the First World War and rose again to 150 by 1927. The Chinese came to Hamburg mainly as seamen and settled mainly in the Chinatown on St. Pauli . They worked in the catering sector, operated laundries or worked in the port. In the 1920s, Hamburg was, alongside Genoa and Marseille, the most important hub for illegal drug trafficking in Europe. In a police report of August 4, 1921, the following is stated:

“The police are aware that there are a number of opium dens in Hamburg, in which not only the coolies and other Chinese who are in Hamburg, but also Japanese and Germans indulge in the consumption of this poison. The police succeeded in locating two of these dangerous places, namely Hafenstrasse 126 and Pinnasberg 77. Under the guise of a green goods store and a laundry, the vice caves had been opened in the basement and enjoyed great popularity. During the overhaul, around 50 people were found in both cellars. The persons concerned were already in the deepest opium intoxication or were found smoking opium. A number of pipes, opium lamps and opium itself were found and confiscated in both opium dens. An investigation has been initiated against the owners of the two opium dens. The discovery of further restaurants is imminent. "

Even in the 1930s there were supposed to have been illegal opium dens on St. Pauli. From the mid-1930s, the small Chinese community in Hamburg was increasingly subject to police surveillance. As part of the so-called Chinese action on May 13, 1944, the last 130 Chinese remaining in Hamburg were arrested and taken to the Fuhlsbüttel police prison for several months . The incarcerated Chinese then had to do forced labor in the Langer Morgen labor education camp . This was the end of the Chinaviertel in Hamburg.

literature

- Matthias Seefelder: Opium , dtv, Munich 1987, ISBN 3-423-11280-8

- Peter Selling: The career of the drug problem in the USA - A study of the course and development forms of social problems , Centaurus-Verlagsgesellschaft, Pfaffenweiler 1989, ISBN 3-89085-207-6

- Peter Selling: On the history of dealing with opiates , in: Sebastian Scheerer, Irmgard Vogt (Ed.): Drugs and drug policy - A manual , Frankfurt / New York, 1989

- Bernd Eberstein: Hamburg-China history of a partnership , Christians, Hamburg 1988

- Wolfgang Schivelbusch: Paradise, Taste and Reason - A History of Luxury Means , Munich / Vienna 1980

- Manfred Kappler: Drugs and Colonialism - On the ideological history of drug use , Frankfurt 1991

- W. Schmidtbauer, J. vom Scheid: Handbuch der Rauschdrogen , Munich 1988

- L. Lewin: Phantastica - The numbing and exciting luxury foods , Volksverlag, Linden 1980 (reprint of the 2nd edition from 1927)

- Sebastian Scheerer: The genesis of the narcotics laws in the Federal Republic of Germany and in the Netherlands , Göttingen 1982

- Fritz Redlich: Drugs and Addictions - World Economic and Sociological Considerations on a Medical Topic , Kurt Schroeder Verlag, Bonn 1929

- Werner Thomas: Drugs and their victims - A correction and addition , in: Kriminalistische Monatshefte - Journal for the entire criminal science and practice, Berlin 1935

- A. Hirschmann: The opium question and its international regulation , dissertation, Tübingen 1912

Web links

- Michael Nanut, Wolfgang Regal: How Opium Was Introduced to the People , in: Doctors Week, Vienna 2007, No. 42

- Ralf Nehmzow: In the middle of Hamburg - a journey through time to Chinatown , in: Hamburger Abendblatt , July 26, 2008

- Lars Amenda: Secret tunnels under St. Pauli? - Rumors about the "Chinese Quarter" in the 1920s , Hamburg 2008

- Opium Museum

- Commissioner Jesse B. Cook (1931-06): San Francisco's old Chinatown

- Jane F. Murphy (1922): The Black Candle - opium smoking in Canada

- "Opium degrading the French Navy"

- HH Kane, MD (September 24, 1881): "American Opium Smokers"

Individual evidence

- ↑ cf. W. Schmidtbauer, J. vom Scheid: Handbuch der Rauschdrogen , Munich 1988, p. 299f.

- ^ Matthias Seefelder: Opium , dtv, Munich 1987, p. 156

- ↑ cf. Peter Selling: The career of the drug problem in the USA - A study on the course and development of social problems , Centaurus-Verlagsgesellschaft, Pfaffenweiler 1989, p. 278 and Seefelder 1990, p. 152f.

- ↑ cf. Michael Nanut, Wolfgang Regal: How opium was brought to the people ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , in: Doctors Week , Vienna 2007, No. 42

- ↑ "American Opium Smokers"

- ↑ cf. Fritz Redlich: Drugs and Addictions - World Economic and Sociological Considerations on a Medical Topic , Kurt Schroeder Verlag, Bonn 1929, p. 48 f.

- ↑ cf. Jane F. Murphy (1922): "The Black Candle - opium smoking in Canada" ( Memento of the original from July 30, 2012 in the web archive archive.today ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ cf. Manfred Kappler: Drugs and Colonialism - On the History of Ideology of Drug Consumption , Frankfurt 1991, p. 293 ff. And Selling 1988, p. 15

- ↑ Peter Selling: On the history of dealing with opiates , in: Sebastian Scheerer, Irmgard Vogt (Ed.): Drugs and drug policy - A manual , Frankfurt / New York, 1989, p. 282

- ↑ cf. Kappler 1991: 295 f .; Selling 1988: 15 f., Scheerer 1982: 23 f., Kappler 1991: 296

- ↑ cf. Selling1988: 15f .; Scheerer 1982: 24.

- ^ Asiatic Exclusion League, quoted in Selling 1988: 16

- ↑ cf. Selling 1988: 16f., Scheerer 1982: 24

- ↑ cf. Selling 1989: 282; Scheerer 1982: 25, Kappler 1991: 299

- ↑ cf. Katharina Steffen: From Remedies to Addictive Substances - The History of Opium, in: Neue Zürcher Zeitung , No. 279, December 2, 1991

- ↑ cf. Honest 1929: 48

- ↑ cf. Bernd Eberstein: Hamburg-China history of a partnership , Christians, Hamburg 1988, p. 253 ff.

- ↑ quoted in: Helmut Ebeling: Black Chronicle of a World City - Hamburg Criminal History 1919 to 1945 , Ernst-Kabel-Verlag, 1980, p. 171 f.

- ↑ cf. Thomas, Werner: Drugs and their victims - a correction and addition , in: Kriminalistische Monatshefte - magazine for the entire criminal science and practice, Berlin 1935 and Lars Amenda: Secret tunnels under St. Pauli? - Rumors about the "Chinese Quarter" in the 1920s , Hamburg 2008