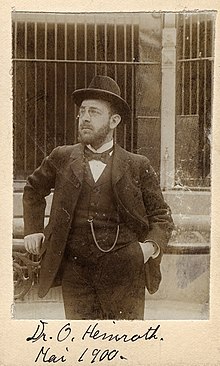

Oskar Heinroth

Oskar Heinroth (born March 1, 1871 in Kastel ; † May 31, 1945 in Berlin ) was a German zoologist . He achieved international scientific importance through his fundamental work on comparative behavioral research in ornithology . He introduced the term ethology into modern behavioral biology in its usual meaning today . From 1911 to 1913 he played a key role in setting up the Berlin Zoo Aquarium , which he headed for more than 30 years. Konrad Lorenz paid tribute to him in 1941 with the words: “Oskar Heinroth was the first on this side of the ocean who came up with the idea of examining the behavior of different animal forms for similarities and differences, for common and divisive things, like the phylogeneticist with physical characteristics has always done. "

Live and act

Oskar Heinroth was born on March 1st, 1871 in Kastel near Mainz . After surviving smallpox in infancy, he retained severe corneal and lens opacities as well as distortions of the iris, a circumstance to which he probably owed his remarkably trained hearing. Heinroth first studied medicine in Leipzig, Halle and Kiel, where he received his doctorate in 1895 with "Investigations on fish urine". In Kiel he had devoted himself extensively to the hunt for water birds and beach birds and observed free-flying gray geese and reptiles. During the second half of his military service as a junior doctor in Hamburg-Altona, he spent his free time in the zoo and voluntarily dissected dead animals. In autumn 1896 he came to Berlin and became a volunteer assistant in the zoological garden and in the zoological museum , where he largely redesigned the bird collection and conducted moulting studies. After returning from the Mencke expedition to the Bismarck Archipelago in 1901, he got a paid assistant position in the Berlin zoo in 1904. As an assistant, he raised almost all European duck species by hand between 1898 and 1913 . In 1906, during crossbreeding attempts on ducks, he discovered that certain behavior patterns, such as diving head into water during courtship , are inheritable and therefore innate. Heinroth also compared the calls and movements of various species of swans and geese during courtship and when their chicks were raised. Through these analyzes, he laid the foundation for a comparative behavioral research that investigates behavioral characteristics in a similar way for phylogenetic relationships and similarities, as was the case with physical characteristics long before. Today many of his studies would be attributed to behavioral ecology .

Oskar Heinroth fell a. a. revealed the strange behavior of chicks that had hatched in isolation in an incubator and came into contact with humans shortly after hatching. If these chicks were then brought to a parent animal, the latter treated the chicks like its own offspring; however, the chicks always fled from their “adoptive parents” with a loud squeak and sought protection from anyone in the vicinity. Heinroth was then able to successfully lead the chicks to adult conspecifics as "adoptive children" if he put them in a sack immediately after hatching, thus preventing any contact with humans. He called this form of learning imprinting and also developed biological terms such as agitation, showing off and shouting triumph .

Konrad Lorenz later adopted this terminology, popularized it and saw himself as a student of Oskar Heinroth throughout his life. In 1931 he explained to him in a letter that he saw in his teacher the founder of a new science, "namely animal psychology as a branch of biology". The name commonly used today for this research area is ethology or comparative behavioral research. It is hardly known today that Douglas Alexander Spalding described the phenomenon of coinage in scientific publications in the second half of the 19th century.

From 1904 on, Heinroth was married to Magdalena, née Wiebe. She worked with him until her death in 1932 and was a co-author of several of his books. Magdalena Heinroth died completely unexpectedly of an acute intestinal obstruction while on vacation in the Danube Delta in Romania. In 1933 he married the zoologist Katharina Berger . In 1936 Heinroth was elected a member of the Leopoldina . For ten years he was chairman of the German Ornithological Society .

Oskar Heinroth died on May 31, 1945 at the age of 74, a few months after the Berlin aquarium was destroyed. He succumbed to the consequences of pneumonia that he suffered towards the beginning of the year between firefighting work at the zoo and stays in damp air raid shelters. While still in the sickbed, he had given instructions on how to treat the wounded in the final battles; while on the other hand he had also wished for death by poison capsules from his time on the expedition. The zoo carpenter made a coffin out of bombed-out door leaves. After the cremation, Oskar Heinroth was buried on August 15, the anniversary of his first wife Magdalena's death, on the zoo grounds.

Fonts

- Contributions to the biology, especially ethology and psychology of the anatids. In: Negotiations of the 5th International Ornithological Congress in Berlin, May 30 to June 4, 1910 . German Ornithological Society, Berlin 1911, pp. 589–702, full text .

- Oskar Heinroth, Magdalena Heinroth: The birds of Central Europe. Photographed in all stages of life and development and observed in their mental life from the egg during the rearing , 4 volumes, Bermühler, Berlin 1924–1934, published by the State Agency for the Preservation of Natural Monuments in Prussia .

- From the life of the birds . Reviewed and completed by Katharina Heinroth. 2nd, improved edition, Springer, Berlin / Göttingen / Heidelberg 1955 (= Understandable Science, Natural Science Department. Volume 34); English edition: 1958.

literature

- Erwin Stresemann : Heinroth, Oskar August. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 8, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1969, ISBN 3-428-00189-3 , p. 436 ( digitized version ).

- Katharina Heinroth : Oskar Heinroth. Father of Behavioral Research 1871-1945 , Scientific Book Society Darmstadt, 1971, ISBN 3-8047-0406-9 .

- Katharina Heinroth: It began with butterflies - my life with animals in Breslau, Munich and Berlin. 2nd Edition. Kindler Verlag, Munich 1979, ISBN 3-463-00745-2 .

- Otto Koenig (Ed.): But why do the cattle have this beak? Letters from early behavioral research 1930-1940. Piper, Munich 1988, ISBN 3-492-10975-6 .

- Konrad Lorenz : Obituary for Oskar Heinroth. In: The Zoological Garden (NF). Volume 24, 1958, pp. 264–274, full text (PDF)

- Kurt Priemel : For Oskar Heinroth's 70th birthday. In: The Zoological Garden (NF). Volume 13, 1941, pp. 133-140.

- Karl Schulze-Hagen, Gabriele Kaiser: The Vogel WG - The Heinroths, their 1000 birds and the beginnings of behavioral research. Knesebeck, Munich 2020, ISBN 978-3-95728-395-5 .

- Günter Tembrock : Oskar Heinroth (1871–1945). In: Ilse Jahn , Michael Schmitt (Ed.): Darwin & Co. A history of biology in portraits. Volume 2, pp. 380-400. Beck, Munich 2001, ISBN 3-406-44639-6 .

Web links

- Literature by and about Oskar Heinroth in the catalog of the German National Library

- Silke Merten: Pioneers in bird research - Oskar and Magdalena Heinroth , SWR2 Wissen, May 27, 2020

Individual evidence

- ↑ Konrad Lorenz : Oskar Heinroth 70 years! In: The Biologist. Volume 10, No. 2–3, 1941, pp. 45–47, full text (PDF)

- ↑ Priemel (1941), p. 136

- ↑ a b c d Priemel (1941), p. 137

- ^ The moorhen Benedict as a razor. In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung No. 87 of April 14, 2020, p. 13.

- ↑ K. Heinroth (1979), pp. 136-145.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Heinroth, Oskar |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Ornithologist and head of the Berlin aquarium |

| DATE OF BIRTH | March 1, 1871 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Mainz-Kastel |

| DATE OF DEATH | May 31, 1945 |

| Place of death | Berlin |