China gemstone factory

| Edelstein AG | |

|---|---|

| legal form | Corporation |

| founding | 1919/23, 1932 |

| resolution | 1973 |

| Seat | Küps , Germany |

| management |

Julius Edelstein 1919–1932 Fritz Greiner 1933–45 / 49-71 |

| Branch | Ceramics |

The Julius Edelstein porcelain factory was a porcelain manufacturer in Küps in the Upper Franconian district of Kronach in Bavaria . The company mainly produced tableware and decorative china. After the Second World War it had its own art department.

Julius Edelstein AG

The company was founded by Julius Edelstein (1882–1941), a porcelain and glass wholesaler in Berlin-Charlottenburg since 1912 at the latest . In 1919 he and his partner Isidor Grünebaum bought the Upper Franconian porcelain factory founded by Friedrich Ohnemüller and Emil Speiser . According to the contract dated May 19, 1919, the purchase price was 280,000 marks. The factory in Kronacher Strasse was renamed Porzellanfabrik Edelstein GmbH , modernized according to plan and the company was converted into a stock corporation in 1923. The distribution took place through the Edelsteinsche Handelsgesellschaft Glas-, Porzellan- und Steingut-Handels AG with seat in Berlin, Alexandrinenstrasse 95/96.

Edelstein developed into a leading brand in Germany. The modern production facilities and the high-quality porcelain received great recognition in the specialist press. Edelstein was able to compete with Philipp Rosenthal on the market . There was also a porcelain wholesaler with a sample warehouse in Eidelstedt . In 1924 a representative office was opened in the Mädlerpassage at the important trade fair location Leipzig . After all, there were showrooms in New York as well .

Edelstein originally sold primarily in East Prussia , where he owned another porcelain factory in Allenstein . The inflation in 1923 favored exports abroad, which was advantageous for a strongly export-oriented consumer goods industry such as porcelain production. On the other hand, like its competitors, Edelstein struggled with the collapse of the domestic market in autumn 1923. From 1926 onwards, the industry suffered from growing protectionism abroad. B. England now a duty of 50 percent. Other important export countries were the USA, Australia, the Netherlands, Switzerland, Romania, Scandinavia and the Baltic States.

In 1926 Grünebaum withdrew from the business. In the following year, Edelstein entered into a loan deal with the Steingutfabrik Colditz AG and its director Otto Zehe. Colditz was considered the largest producer of earthenware at the time and quickly expanded its holdings in the company. This development also affected Schönwald , taken over by Kahla , as well as Tirschenreuth and Bauscher , who went to Lorenz Hutschenreuther .

As a result of the global economic crisis from October 1929, Colditz was able to force Edelstein-AG into bankruptcy on September 20, 1932, although the loans had been regularly serviced. As compensation for outstanding claims, the Küpser factory and the Berlin trading company became the property of Colditz.

Julius Edelstein was only partially compensated by shares in the Beyer & Bock porcelain factory , whose plant in Volkstedt, Thuringia, he headed from 1933. When the National Socialists came to power , the Jewish entrepreneur Edelstein no longer had any prospects of influencing the bankruptcy proceedings in his favor. The former owner and his wife Margaretha were deported to Riga in 1941 and murdered.

production

The first renovation work in Küps was completed on October 1st, 1920: The sanitary facilities now met the hygienic standards; there was a mass mill with six drums, a new warehouse, and an expedition with a loading ramp. From here the goods went on horse-drawn vehicles to the nearby Küps train station. On December 18, 1921, the old factory building was destroyed by a major fire, the kilns and the new outbuildings remained intact. A new building was completed in the following year, including the machine house and steam boiler. In 1924 six ovens were in operation. This factory shaped the townscape of Küps until it was demolished in 1986.

At the height of its economic success in 1926, Edelstein employed around 600 people.

The management was held by Albert Kindermann from 1919 to 1923. He was followed by director Carl Elstner (1880–1932). He had previously worked for Rosenthal as an authorized signatory for 20 years . Since he took some skilled workers with him from Selb to Küps, legal disputes with Rosenthal repeatedly arose in the period that followed because of decor similarities. Edelstein AG was represented in these proceedings by Thomas Dehler .

The modeller Theodor Gack (1894–1984) was associated with the company for many years, first from 1923 to 1940, then again from 1944 and 1954 for the second time. Until 1959 he managed the company as technical director.

range

Designs for gem supplied & a. Richard Riemerschmid . The focus of the range, however, was on historicizing forms of the baroque, third rococo and empire with plenty of relief and floral decoration and gilding. The thin, transparent shards of the top products were a specialty . The offer also included splendid services fully decorated with silver.

The following were commercially successful:

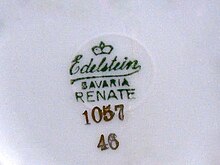

- Mocha service Renate

- Agathe dinner service , 1926, with cheerful scattered flowers

- Cosima , etched gold decor

Edelstein Porzellanfabrik AG

Edelstein's liabilities totaled 1.36 million Reichsmarks in 1932, a good half of which went to Colditz AG. Otto Zehe personally had claims in the amount of 100,000 marks, which earned him the charge in his own company of having mixed business and private interests. After the stock market crash in 1932, the takeover was completed. On December 1, 1932, a new stock corporation was established, initially under the name Porzellanfabrik J. Edelstein AG . The capital was entirely in Colditz's hands. In 1934 the company's headquarters were relocated from Berlin to Küps.

Fritz Greiner (1903–1974), NSDAP member and active in the NSKK , took over the management. He kept it - with a five-year break after the end of the war - until 1971. Otto Zehe died in 1935. On May 22, 1937, the name was again changed to Edelstein Porzellanfabrik AG . As early as 1935, the company had been obliged to justify their Jewish names public: In the gauamtlichen newspaper Bayerische Ostmark she let u. a. It is said that the gemstone stands for “nobility”, the well-known brand name betrays tradition and thus justifies the buyer's trust.

The company complied with the requirements of the German Labor Front without resistance : The company organization was hierarchized according to the leader principle , canteen and company sports were introduced. It was spread with pride that it was the first company in Upper Franconia to have joined the DAF. The number of employees rose continuously from 115 in 1932 to 375 (1937). With 50 apprentices at times, Edelstein had a very young workforce. During the Second World War , up to 36 French prisoners of war could be used in the factory halls. The ten Eastern workers and six Armenian foreign workers only made up a comparatively small proportion.

range

With the changed market situation from 1932/33, the production of figurines and knickknacks fell sharply. Feston tableware has now been brought onto the market for this, which could be offered in moderate quality about 20 percent cheaper. The Baroque-style complete Maria Theresa service , designed by Ludwig Gack for the more conservative taste, can be found in the lists of goods until 1943, but during the war, mainly Wehrmacht porcelain with thick shards was produced.

"Economic miracle" time

Despite the damage to the factory when the US Army moved in and initial material shortages after the end of the war, Edelstein employed around 350 people in the 1950s. The range was initially drawn from the old stock of molds, individual service parts were added from other series. The Maria Theresia service was also offered again, now glazed ivory with a purple steel print overglaze.

In the meantime, Julius Edelstein's daughter, Marianne Wald (later Orlando) tried to get the company back. At that time she was working for the British military government in the Rhineland and was in contact with the mayor of Küps, Ernst Hanna. Ultimately, claims for restitution were futile because Military Government Law No. 59 only covered theft of Jewish property after January 30, 1933. Marianne Wald also tried to support the acting director Walter Dörfel in order to prevent a return of the Nazi-burdened Fritz Greiner.

Edelstein was back in the profit zone as early as 1946, and in 1949 the factory even employed 400 workers.

Edelstein went to the Slater Walker Bank in 1972 with the company's mother, Colditz (based in Staffel / Lahn ). At that time the annual turnover was 5.4 million DM, the export share about 45 percent. In the following year, Edelstein was passed on to Heinrich Porzellan GmbH. She had production shut down on December 31, 1973 and sold the property. The Edelstein director's villa was sold to the Catholic Church and used as a rectory.

range

The temporary art department received designs by Kurt Wendler and Richard Scheibe , which are still worth seeing today. Sebastiano Buscetta created animal sculptures and the “negro busts” so typical of the 1950s. Alfred relief and bisque porcelain modeled in a turban style .

The tableware series of the 1960s then followed the trend towards contemporary shapes and trendy decors, including Astrid , 900 , Carat , Jeunesse and Liane .

See also

List of porcelain manufacturers and manufacturers

Individual evidence

- ^ Robert E. Röntgen: German porcelain brands. P. 172.

- ↑ Horst Makus: Ceramics of the 50s. Shapes, colors and decors. A manual . Stuttgart 2005, ISBN 3-89790-220-6 , p. 380 f.

- ↑ Bernd Wollner, Achim Bühler: 170 years of porcelain. How Küps made history . Küps 2001, p. 62.

- ↑ Wollner / Bühler: 170 years of porcelain . P. 70.

- ↑ Petra Werner: The Twenties. German porcelain between inflation and depression. The Art Deco era? , Hohenberg / Eger 1992, p. 5 f.

- ↑ Wollner / Bühler: 170 years of porcelain . P. 103.

- ↑ Wollner, Bühler: 170 years of porcelain. P. 73.

- ↑ Inventory 20912 Steingutfabrik Colditz AG. Detailed introduction of the Saxon State Archives, accessed on January 25, 2015.

- ↑ Wollner / Bühler: 170 years of porcelain. P. 150.

- ^ Alfred Gottwaldt, Diana Schulle: The "Deportations of Jews" from the German Reich 1941–1945. An annotated chronology. Marix, Wiesbaden 2005, ISBN 3-86539-059-5 , p. 121.

- ↑ Wollner, Bühler: 170 years of porcelain. P. 68

- ↑ Wollner, Bühler: 170 years of porcelain. P. 76 ff.

- ^ Elisabeth Trux, Petra Werner (arr.): The Helga Schalk-Thielmann Collection , Vol. 2. Hohenberg / Eger 2001, pp. 32–39.

- ↑ Wollner / Bühler: 170 years of porcelain . P. 114.

- ^ Quote from Wollner / Bühler: 170 years of porcelain . P. 128.

- ↑ Wollner / Bühler: 170 years of porcelain . P. 129.

- ↑ See Wollner / Bühler: 170 years of porcelain . P. 129.

- ↑ See Wollner / Bühler: 170 years of porcelain . P. 183.

- ↑ Trux / Werner, p. 35.

literature

- Bernd Wollner, Achim Bühler: 170 years of porcelain. How Küps made history . Küps 2001, ISBN 3-00-007759-6 , pp. 61-276.

- Horst Makus: Ceramic from the 50s. Shapes, colors and decors. A manual . Arnoldsche Verlagsanstalt, Stuttgart 2005, ISBN 3-89790-220-6 .

- Robert E. Röntgen: German porcelain brands from 1710 until today. 6th edition. Battenberg, Regenstauf 2007, ISBN 978-3-86646-013-3 .

- The New York Community Trust (Ed.): Marianne Edelstein Orlando 1918–1990. New York no year (online version PDF)