Riehenteich

|

Riehenteich dialect: Riechedych |

||

|

Riehenteich shortly after the Schliessi weir at the introduction of the new pond, which also branches off from the meadow further upstream (right) |

||

| Data | ||

| location | Canton of Basel-Stadt , Switzerland | |

| River system | Rhine | |

| Drain over | Meadow (river) → Rhine → North Sea | |

| source | Flood wave with derivation from the meadow 47 ° 34 ′ 38 ″ N , 7 ° 37 ′ 21 ″ E |

|

| muzzle | After the Riehenteich power station, underground return line to the meadow; historically in two outlets in the Rhine, on the one hand at Neuer Mühle and Ziegelmühle (until 1907), on the other hand at the monastery building Kleines Klingental (until 1917) Coordinates: 47 ° 34 ′ 43 ″ N , 7 ° 37 ′ 27 ″ E ; CH1903: 613967 / 269 772 47 ° 34 '43 " N , 7 ° 37' 27" O

|

|

The Riehenteich in the canton of Basel-Stadt (also called Kleinbasler Teich up to the beginning of the 20th century ) is an artificial river that drains around 5 m³ / s of water from the Wiese river over a distance of 3.8 kilometers; it thus takes up almost half of the meadow's mean water flow. Built in the middle of the 13th century, the Riehenteich served as a commercial canal for various water use interests and flowed into the Rhine . As a technically obsolete structure, it was largely shut down in two stages in 1907/17. Only part of it is still preserved, which has been leading to the Riehenteich power station (a groundwater pumping station ) in the Lange Erlen forest park since 1923 and back underground again to the meadow. The production opportunities associated with the canal led to the development of Kleinbasel as an industrial location in the 19th century .

Construction and use

Originally only on the left bank of the Rhine, the episcopal city of Basel experienced steady growth and expansion of its commercial activity as a regional center and transport hub. In front of the Kleinbasler Riehenteich, the Grossbasler industrial sewers St. Alban-Teich and Rümelinbach , built in the 12th century, were already in operation. The power politics of the Basel bishops aimed at the Black Forest at the beginning of the 13th century, after the Zähringer died out , manifested itself in the construction of the first Basel bridge over the Rhine and in the establishment of the Kleinbasel on the right bank of the Rhine in 1225. Its original infrastructure also belonged to its original infrastructure the roughly four kilometers long Riehenteich. The earliest mention of the canal and two mills dates back to 1251. The Cistercian monastery Wettingen is believed to be the investor , and it was already owned in Riehen . A servant of the bishop, bread master Heinrich von Ravensburg, also played a decisive role in the construction of the canal and put himself and his family in key ownership positions. Possibly using an old creek bed, water was diverted from the meadow by means of a weir near the Riehen municipal boundary and brought to the southern Riehentor . There, the canal, running north along the city wall , supported the fortifications. After the Clarakirche he was led through the wall into the city and fed first one, then as the main pond together with the bread master pond branched off from it as a secondary canal in 1262, three parallel canals ( lower, middle, upper pond ), which in two outlets into the Rhine flowed. This water system was expanded by 1280 at the latest. In the middle of the 14th century, a system of urban channels or streams appears to have been created, which was in operation until the middle of the 19th century. Finally, around 1460, a short tributary was added at the hook of the main pond in front of the city wall. The use of water and hydropower was allowed by means of numerous fiefs , the users organized themselves in a corporation . The number of mills within the city walls (eight at the rear pond, eight at the middle pond and three at the front pond) did not change from the middle of the 14th century until the 19th century. In front of the city, three fiefs were awarded, which increased to six by the 19th century, four of them with hydropower. These extra-urban mills included the two metalworking fiefs of the Drahtzug , where the bread master pond and the main pond reunited. They were specially protected by the Clara bulwark in the 1620s and integrated into the fastening ring.

The hydropower primarily drove flour mills. There was also a wide variety of sawing, stamping, milling, hammering and grinding. The use of many mills has changed again and again over the centuries. In the 19th century in particular, specialization and diversification began to grow. An inventory from 1826 included 26 mills with 64 wheels in the mills. 34 of the wheels were used on grain mills, the other wheels drove 6 tobacco pounders, 4 saws, 3 plaster mills, 4 colored wood mills, 4 oil mills, 2 bleaching rollers, 2 colored wood cutters, 2 poison mills, 2 sand pounders, 2 loops, 1 woolen cloth mill, 1 spice mill, 1 indigo mill, 1 wale stamp, 1 fulling stocking, 1 fulling barrel for leather and 1 hammer for the tanners. In addition to generating energy, the sewer water also served other purposes: transport (wood rafts), hygiene (sewer system and bathing rooms), protection (fire fighting and fastening) and as a solvent (tannery, bleaching, dyeing). The latter gained outstanding importance in the 19th century when a dye industry developed in Basel in the context of traditional silk ribbon manufacture and from this the Basel chemical industry ( Clavel , Geigy , Sandoz ) developed. These industries were dependent on the water of the Riehenteich (or meadow), as it was poor in lime and therefore very suitable for production processes.

Repeal

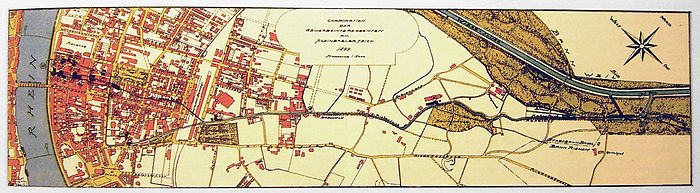

The strong industrialization of Basel with the ever larger factories in the second half of the 19th century brought with it a rapidly growing demand for transport connections, space and energy, which the closely knit Kleinbasel and the Riehenteich with its power output of a little more than 400 hp soon no longer meet sufficed. The production sites moved to the city (new quarters Klybeck and Rosental ), and steam engines were increasingly used. The construction of the second Badischer Bahnhof made discussions about the relocation of the Riehenteich crossing it, which assumed a fundamental character. Sanitary issues came to the fore: The pollution of the pond residents through damp apartments and the factory sewage and faeces that were let into the canal. After the canton bought the corporation's water rights, the Upper and Middle Pond and the Krumme Pond were shut down in 1907 and the Lower Pond and the Main Pond in 1917. In the place of water power there were power lines, the lime-poor pond water was supplied by means of an underground pipe until the middle of the 20th century. The Riehenteich remained in the Lange Erlen forest area . It leads over around 800 meters from its discharge on the Schliessi out of the meadow to the turbines of the Riehenteich power plant built in 1923. This supports the power supply for the pumping systems in the Langen Erlen, where around half of Basel's drinking water is obtained by means of groundwater recharge .

In the urban area, the canal has been almost completely removed or built over. Stone arches of vaulted canal parts are only visible in two places (in a floor opening of the Untere Rheinweg and on the back of the former monastery building Kleines Klingental ). Part of the vault for the Krummen Teich near the wire draw is still preserved underground . In addition, the streets Teichgässlein and Riehenteichstrasse take up the old canal course. Sägergässlein , Hammerstrasse and Bleicheweg are reminiscent of earlier businesses that used the water of the Riehenteich. The Badgässlein was closed in the course of the partially complete redevelopment of the district at the beginning of the 20th century. Most of the mills were demolished. In three of the six surviving buildings, however, only the facade still retains the mill architecture. Just a few years after its disappearance, the Riehenteich became a motif in Basel's native literature , something which the dialect writer Theobald Baerwart (1872–1942) stands for with his prose texts and poems ( Der Riechedych ).

literature

- Eduard Schweizer: The trades at the Kleinbasler pond. In. Basel magazine for history and archeology . Vol. 26. Basel 1927. pp. 1-71. Vol. 27. Basel 1928. pp. 1–114. Vol. 28 Basel 1929. pp. 1-140.

- Thomas Lutz: The art monuments of the canton of Basel-Stadt. Vol. VI: The old town of Kleinbasel; Secular buildings. Bern 2004. (Chapter mills and ponds , pp. 29–56.)

- Daniel Rüetschi: Basler drinking water production in the long alders. Biological cleaning services in the wooded water bodies. Dissertation University of Basel. Basel 2004. (PDF; 30.1 MB)

- Berthold Moog: Ponds and mills in Basel. In: Mill letter - Lettre des Moulins. No. 11 (2008). Pp. 9-15. (PDF; 4.1 MB)

Web links

References and comments

- ↑ Start of construction in 1225, completion of the entire canal system in 1280

- ↑ Basel Buildings Riehenteich. Retrieved August 5, 2015