Sangaku

Sangaku ( Japanese 算 額 , literally 'mathematical boards') are artistically painted wooden boards that show geometric tasks or puzzles. They were hung in Japan during the Edo period (1603-1867) by members of all social classes in Shinto shrines and Buddhist temples . There they served not only as offerings , but also as an intellectual challenge for the pilgrims who followed. In this respect one speaks of "Japanese temple geometry".

history

The Sangaku originated during the Edo period, when Japan - almost completely isolated from the western world - developed its own mathematics tradition (Japanese: Wasan ). Even before the rise of the Sangaku it was customary to hang painted wooden panels as offerings in temples; they showed - as a substitute for an expensive sacrificial animal - this in pictorial representation. The first wooden panels with geometric motifs were probably created in the middle of the 17th century. Today it is assumed that the highly educated members of the samurai class were initially the originators, but that farmers, women and even young people increasingly practiced sangaku. In this respect, the Sangaku can be assigned to entertainment mathematics.

Most Sangaku tablets have the name of the maker and a date. The oldest tablet still preserved today dates from 1683. The Sangaku texts are written in Kanbun , i. that is, they were written in Japanese in Classical Chinese , which few people can speak today. Many sangaku have been destroyed over the centuries, along with the temples that housed them; today, however, more than 880 have survived all over Japan. An interactive map is available on the Internet that shows the locations and images of the boards.

The study of Sangaku was largely initiated and promoted by Hidetoshi Fukagawa, a doctor of math and a teacher at a high school. After coming across the topic in 1969 and realizing the current value of the Sangaku, for example for school lessons, he tried (initially in vain) to interest western geometrists in Japanese temple geometry, which was still completely unknown in the West. Finally he was able to win the British mathematician Daniel Pedoe for a collaboration and together they published the first English-language Sangaku collection in 1989 (see literature). Fukagawa, who first had to learn Kanbun, the language of Sangaku, for his research, is now regarded as the world's leading Sangaku expert.

object

The tasks on the Sangaku mainly come from the area of classical Euclidean geometry . They often deal with touching circles , ellipses and triangles and differ significantly from the geometric tasks that are common in Western schools. The Sangaku only show the problem and possibly the final solution, but not the detailed solution. In this respect, they are also to be understood as an intellectual challenge to subsequent temple visitors. The demands placed on the audience are very different: there are tasks that a student should be able to solve in the first semester, and those that can hardly be mastered without advanced methods such as affine transformation or analysis . Not infrequently, the findings of Western mathematicians were also anticipated, such as Casey's theorem , the Malfatti circles or the Soddy hexlet . The Steiner chain was already the subject of a sangaku at the time when Jakob Steiner postulated it in Europe.

In addition to the geometric questions, some Sangaku also address non-geometric problems such as Diophantine equations or the calculation of the volumes of bodies with curved surfaces.

Examples

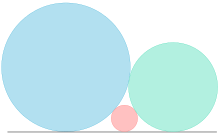

The two diagrams show two typical Sangaku problems; they come from the prefecture of Gunma from the years 1824 (example 1) and 1803 (example 2).

example 1

Three touching circles have a common tangent (horizontal black line in the illustration). The radii of the two outer, larger circles are given (light blue and light green in the figure); how big is the middle (pink) circle? The relationship between the three radii is sought.

The answer is:

A derivation can be found in Hartmann: Sangaku - Japanese Temple Geometry , 2008.

Example 2

A horizontal straight line (black) is drawn through its center in a circle (the large, beige-colored one in the illustration). An isosceles triangle sits with its base on this straight line, its apex and the right base corner point lie on the circle. The center of another circle (light blue) is also on the straight line; this circle touches the large circle from the inside and goes through the left base corner of the triangle. A third circle (green) is now inscribed in such a way that it touches the large circle from the inside and the smaller, blue circle and the triangle from the outside.

Task: Prove that the connection between the center of the green circle and the point of contact between the blue circle and the triangle is perpendicular to the horizontal line.

Ingmar Rubin describes one possible demonstration at www.matheraetsel.de.

Example 3

The following riddle comes from a Sangaku tablet from 1743 (an example of a non-geometric problem): 50 animals - rabbits and chickens - have a total of 122 feet. How many rabbits and how many chickens are there?

See also

- Japanese phrase for polygons inscribed in a circle

- Japanese theorem for concyclic quadrilaterals

- Entertainment math

Individual evidence

- ↑ Hiroshi Kotera: Japanese Temple Geometry Problem. www.wasan.jp , accessed July 2, 2013 .

- ^ Fukagawa, Rothman: Sacred Mathematics , 2008. p. 83

- ↑ Rothman, Fukakawa: Japanese Temple Geometry , 1989, p 86 ff, 91st

- ↑ Christiane Hartmann: Sangaku - Japanese temple geometry. ( MS Word ; 3.3 MB) Term paper for the state examination. Julius-Maximilians-Universität Würzburg , 2008, pp. 25–27 , accessed on July 2, 2013 .

- ↑ Ingmar Rubin: Sangaku problems. (PDF; 195 kB) www.matheraetsel.de , p. 30 f , accessed on July 2, 2013 .

- ^ Fukagawa, Rothman: Sacred Mathematics , 2008. p. 92.

literature

- Hidetoshi Fukagawa, Tony Rothman: Sacred Mathematics - Japanese Temple Geometry . Princeton University Press , Princeton and Oxford 2008, ISBN 978-0-691-12745-3 .

- Hidetoshi Fukagawa, Daniel Pedoe : Japanese Temple Geometry Problems - San Gaku . Charles Babbage Research Foundation, Winnipeg, Canada 1989, ISBN 978-0-919611-21-4 .

- Tony Rothman, Hidetoshi Fukagawa: Japanese Temple Geometry . In: Scientific American . May 1989, p. 84-91 . ( online ; PDF; 1.1 MB)

- Hidetoshi Fukagawa, Tony Rothman: Sangaku: Japanese Geometry . In: Spectrum of Science . No. 7 , 1998, pp. 80 . ( online , paid)

Web links

- Ingmar Rubin: Sangaku problems (PDF; 195 kB) at www.matheraetsel.de (examples with solutions)

- Example task with solution in Archimedes' Laboratory (English)

- Hiroshi Okumura: Japanese Mathematics (PDF; 258 kB) in the Ethnomathematics Digital Library (comparison with modern mathematics, English)

- Christiane Hartmann: Sangaku - Japanese temple geometry ( MS Word ; 3.3 MB). Housework for the state examination. Julius Maximilians University of Würzburg . 2008

- Sangaku: Math test as an offering on https://kawaraban.de