Pubic bone inflammation

| Classification according to ICD-10 | |

|---|---|

| M85.3 | Ostitis condensans |

| ICD-10 online (WHO version 2019) | |

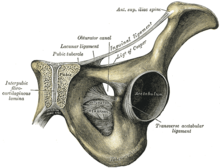

A osteitis pubis ( lat. Osteitis pubis or osteitis pubis ), also Pubalgia called, is a painful non- infectious inflammation of the symphysis pubis ( pubic symphysis ) pubis bone ( pubic bone ) and of nearby structures such as adductor muscles , abdominal muscles and fascia .

Incidence

Pubic bone inflammation primarily affects competitive athletes in sports with sprints, shooting elements and rapid changes of direction, such as foot , hand and basketball players , tennis players and runners . The incidence of pubic bone inflammation in athletes is between 0.5 and 7 percent. Usually men are affected by this disease. Their average age is around 30 years. The average age of sick women is 35 years. The highest incidence is found in soccer players. Of 811 sports students examined in 1995, 1.7 percent suffered from pubic bone inflammation, with the male: female gender ratio of 5: 1 among those affected.

History and diagnosis

Most patients with pubic inflammation have pain when walking, climbing stairs and standing on one leg. The pain can be localized to the pubic symphysis and pubic branches or can extend beyond the groin and hip areas . The pain can reach as far as the lower abdominal muscles , such as the pelvic floor muscles , and become so severe that it leads to longer breaks in competition and training for the person concerned. During the palpatory examination (palpation), the affected patient feels a pressure pain over the pubic symphysis and the pubic branches typical of this clinical picture. Unilateral or bilateral pressure over the adductor base also leads to a characteristic pain picture.

For differential diagnosis, muscular imbalances , blockages of the sacroiliac joint , unilateral pelvic depression , inguinal hernia , nerve constriction syndromes , insertion tendons , adductor strains and urogenital diseases must be excluded. For safe diagnosis can be a local anesthesia ( local anesthesia ) of the pubic symphysis, during the application of imaging procedures is performed ( image intensifier are) used. Under certain circumstances, elevated levels of C-reactive protein can be measured in the blood plasma , while otherwise there are no abnormal laboratory values - generated by pubic bone inflammation.

Imaging procedures

roentgen

In the X-ray image are at a posterior-anterior -projection (anteroposterior projection, from front to back) due to the subchondral sclerosis , erosions visible above the pubic symphysis and other processes, the pubic bone abnormalities. The pubic symphysis gap is usually larger than 10 mm. With an AP projection of the pubic symphysis, which is carried out alternately on the left and right foot (“flamingo image”), a vertical displacement of the pubic symphysis by more than 2 mm can be determined on the side under load.

Skeletal scintigraphy

With the help of three-phase skeletal scintigraphy with 99m technetium- labeled bisphosphonates , pubic bone inflammation can be distinguished from osteomyelitis . While the tracer accumulates in all three phases of osteomyelitis , this is only the case in the late phase (mineralization phase) of pubic bone inflammation.

Magnetic resonance imaging

T 2 -weighted magnetic resonance imaging can show periarticular subchondral bone marrow edema , fluid retention in the pubic symphysis and periarticular edema in acute pubic bone inflammation . Chronic diseases are characterized by subchondral sclerosis and resorption, osteophytes and other changes in the bone.

etiology

The cause of a pubic bone inflammation is an overload of the pubic symphysis as a result of exercise, which leads to irritation (abacterial). The pubic symphysis holds the pelvic ring together and enables the pubic bones to be shifted by a few millimeters. A high level of sporting activity, but also possible anatomical instability, can lead to a local inflammatory reaction. This is particularly the case when the hip mobility is restricted, there is high repetitive shear stress on the pelvic ring, the adductor muscles on the lower pubic branch ( Ramus inferior ossis pubis ) are overloaded and the sacroiliac joints are unstable. The mechanical stress on the pubic symphysis leads to repair processes in which granulation tissue and resorption zones of adjacent bones sprout.

Prevention

Various exercises that serve to build up and stabilize the abdominal and core muscles can prevent pubic inflammation. Adductor stretching exercises are also preventative. An improvement in motor skills, like the correction of biomechanical balance disorders, can also have a preventive effect.

therapy

Pubic bone inflammation is usually treated conservatively at first. This includes the oral intake of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs ( " anti-inflammatory drugs "), rare oral corticosteroids , various physical therapies such as cryotherapy and electrotherapy and physiotherapy exercises . The latter mainly serve to strengthen the core and pelvic floor muscles. This also includes stretching exercises for the adductor muscles. A break from sport also promotes healing, but often not in the patient's interest.

If the conservative measures are unsuccessful, the last resort is surgery. A curettage is essentially only carried out in competitive athletes; in most cases it leads to permanent healing.

Supplementary differential diagnosis

Due to the often very long downtime of athletes, especially soccer players, a stress fracture ( bone bruise ) in the pubic branch must also be considered in the differential diagnosis . Stress fracture lines were seen relatively frequently in control MRI examinations and thin-slice computed tomography (bone window). So it is not just an inflammation. In this case, the therapy is based on absolute sports leave ; Cortisone applications are usually avoided. The possibility of surgical notching of the gracilis muscle (gracilis tenotomy) and part of the adductor longus muscle close to the bone to reduce tendon tension on the anterior pubic branch (tensile forces on the diseased bone) can be considered in this context.

Initial description

The pubic bone inflammation was first described in 1924 by the American Edwin Beer (1876-1938). The term Osteitis pubis was coined in 1930 by HL Kretschmer and WP Sights. For the first time in an athlete - a fencer - the disease was described in 1932 by A. Spinelli.

literature

- M. Wulzinger: Weak middle . In: Der Spiegel . No. 39 , 2004, p. 202 ( online ).

Reference books

- R. Schubert: Indications for MRI: Guidelines for referrers. ABW Wissenschaftsverlag, 2008, ISBN 3-936072-88-4 , p. 91. Limited preview in the Google book search

Review article

- S. Pauli, P. Willemsen, K. Declerck, R. Chappel, M. Vanderveken: Osteomyelitis pubis versus osteitis pubis: a case presentation and review of the literature. In: British journal of sports medicine. Volume 36, Number 1, February 2002, pp. 71-73, PMID 11867499 , PMC 1724464 (free full text) (review).

- SK Andrews, PJ Carek: Osteitis pubis: a diagnosis for the family physician. In: J Am Board Fam Pract 11, 1998, pp. 291-295. PMID 9719351

- SS Lentz: Osteitis pubis: a review. In: Obstet Gynecol Surv 50, 1995, pp. 310-315. PMID 7783998

Original research

- CA Webb, ML Jimenez: What is your diagnosis? Osteitis pubis. In: JAAPA 21, 2008, p. 68. PMID 19253598

- H. Paajanen et al. a .: Pubic magnetic resonance imaging findings in surgically and conservatively treated athletes with osteitis pubis compared to asymptomatic athletes during heavy training. In: Am J Sports Med 36, 2008, pp. 117-121. PMID 17702996

Individual evidence

- ↑ medrapid.info: pubic bone inflammation. ( Memento of the original from May 22, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Retrieved February 11, 2010

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i S. Hopp u. a .: Osteitis pubis. ( Memento from November 23, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 140 kB) In: Deutsche Zeitschrift für Sportmedizin 59, 2008, pp. 100–101.

- ↑ a b R. M. Aigner: pelvis, hip. Georg Thieme Verlag, 2004, ISBN 3-13-126221-4 , pp. 502-506. limited preview in Google Book search

- ↑ PA Fricker u. a .: Osteitis pubis in athletes: Infection, inflammation or injury? In: Sports Med 12, 1991, pp. 266-279. PMID 1784877

- ↑ C. Rodriguez, A. Miguel, H. Lima, K. Heinrichs: Osteitis Pubis Syndrome in the Professional Soccer Athlete: A Case Report. In: Journal of athletic training. Volume 36, Number 4, December 2001, pp. 437-440, PMID 12937486 , PMC 155442 (free full text).

- ↑ a b R. Mehin u. a .: Surgery for osteitis pubis. In: Can J Surg 49, 2006, pp. 170-176. PMID 16749977

- ↑ B. Kunduracioglu et al. a .: Magnetic resonance findings of osteitis pubis. In: J Magn Reson Imaging 25, 2007, pp. 535-539. PMID 17326088

- ^ T. Grieser: The pubic ostitis. In: German Journal for Sports Medicine , 2009 (60), No. 6.

- ^ R. Colp: Edwin Beer 1876-1938. In: Annals of surgery. Volume 110, Number 4, October 1939, pp. 795-796, PMID 17857490 , PMC 1391419 (free full text).

- ↑ E. Beer: Periostitis of the symphysis and descending rami of the pubis following suprapubic operations. In: Intervat J Med & Surg 37, 1924, pp. 224-225.

- ↑ International Society of Arthroscopy, Knee Surgery & Orthopedic Sports Medicine: Instructional Course Lecture No. 105: Groin Pain in Soccer Players. Retrieved February 11, 2010.

- ^ HL Kretschmer, WP Sights: Periostitis and ostitis pubis following supra-pubic prostatectomy: report of a case with recovery. In: J Urol . 23, 1930, pp. 573-580.

- ↑ BD Stutter: The complications of osteitis pubis including a report of a case of sequestrum formation giving rise to persistent purulent urethritis. In: British Journal of Surgery 42, 1954, pp. 164-172. doi: 10.1002 / bjs.18004217208

- ^ R. Johnson: Osteitis pubis. In: Curr Sports Med Rep 2, 2003, pp. 98-102. PMID 12831666

- ↑ A. Spinelli: Nuova mallattia sportive: la pubalgia degli schernitori. In: Ortopedia e Traumatologia Dell Apparato Motore 4, 1932, pp. 111-127.