Battle of the Rhone

| date | September 218 BC Chr. |

|---|---|

| place | On the lower reaches of the Rhone , probably near Orange |

| output | Carthaginian victory |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

| Commander | |

|

unknown |

|

| Troop strength | |

| 38,000 infantry, 8,000 cavalry, 37 elephants |

unknown |

| losses | |

|

unknown |

unknown |

Saguntum - Lilybaeum II - Rhone - Ticinus - Trebia - Cissa - Lake Trasimeno - Ager Falernus - Geronium - Cannae - Nola I - Nola II - Ibera - Cornus - Nola III - Beneventum I - Syracuse - Tarentum I - Capua I - Beneventum II - Silarus - Herdonia I - Upper Baetis - Capua II - Herdonia II - Numistro - Asculum - Tarentum II - New Carthage - Baecula - Grumentum - Metaurus - Ilipa - Crotona - Large fields - Cirta - Zama

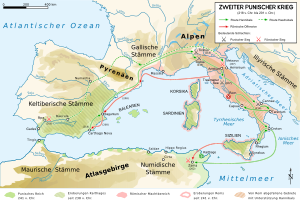

The Battle of the Rhone took place at the end of September 218 BC. Between the troops of the Carthaginian general Hannibal and the Celtic tribe of the Volcae . This battle of the Second Punic War was the first that Hannibal won outside the Carthaginian sphere of influence. The battle probably took place near what is now Orange .

The Volcae, allied with the Romans, set up camp on the eastern side of the Rhone to prevent the Carthaginians from crossing the river and thus counter a Carthaginian invasion of Italy. When Hannibal found out about the Volcae camp on the east bank of the Rhone, he ordered Hanno to cross the river with a smaller force at a distant point and attack the Celts from behind. After Hanno had set up his troops unnoticed in the rear of the Volcae, he gave Hannibal signals to attack and the Volcae were defeated in the ensuing encircling battle.

prehistory

After the siege of Saguntum , which was successful for the Carthaginians , Hannibal sent his troops to winter quarters. With the beginning of the summer of 218 BC He began to set up his armies again and to distribute them over the Carthaginian sphere of influence. 15,000 men and 21 elephants remained on the Iberian Peninsula as protection from raids. He sent 20,000 men, including 4,000 garrison troops for Carthage , to Africa . With the main force, an estimated 90,000 infantry (with allies), 12,000 cavalry and 37 elephants, he marched towards Italy.

The Romans sent Publius Cornelius Scipio with two legions and about 15,000 allies to meet Hannibal. The force was relatively small due to the use of other parts of the Roman army to suppress rebellions by the Gallic Boier and Celtic Insubrians, who lived in northern Italy .

The battle

Hannibal marched in May 218 BC. From Cartagena in three army columns over the Ebro and the Pyrenees towards the Alps . He had to leave about 20,000 men behind on the Iberian Peninsula to protect the newly conquered country from revolts by local peoples or possible invasions by the Romans. However, he was able to increase his army, which had now shrunk to around 50,000 men, with many troops from allied Celtic tribes. As a good diplomat, he had succeeded in making many chiefs north of the Pyrenees his allies against Rome. When he reached the Rhone at the end of September, he set up camp on the west side of the river, within sight of the Celtic troops.

After camping on the bank of the river for three days, he sent Hanno, son of Bomilkar , up the banks of the Rhone. There he was supposed to cross a shallow part of the Rhone with a small, fast force of cavalry and light infantry in order to bypass the Volcae. When Hanno found a suitable place 30 km from Hannibal's camp, he had his troops transferred with the help of rafts and puffed up animal skins. After the Carthaginians had crossed, they waited for night to fall and marched south to line up behind the Volcae camp at dawn.

Hanno gave Hannibal the signal to attack with smoke and light signals. The main force of the Carthaginians began to cross the river, which was about a kilometer wide. The Numidian cavalry tied their horses to rafts or boats and crossed the river relatively quickly. The foot troops crossed the river by swimming or in hurriedly made small wooden boats. After the Carthaginian forces began to gather on the eastern bank, the Volcae, who had watched the crossing of the river, attacked immediately. Meanwhile, Hanno and his troops had set fire to the Volcae camp and attacked the completely surprised Celts from behind. They tried to defend their camp, but most of their troops panicked and fled.

consequences

The main part of the Carthaginian army crossed the Rhone with the help of ships after the battle. Some of the elephants were transported across the river on rafts. After the entire army had crossed the river, Hannibal sent mounted scouts. One of these cavalry detachments met a Scipios advance detachment and had to withdraw after a short battle. After a five-day voyage, Scipio went ashore on the Ligurian coast near present-day Marseille . After exploring the surrounding area and realizing that the Carthaginians were still nearby, he marched towards their camp on the Rhone. When he got there, however, Hannibal had left three days earlier. Scipio then returned to Marseille and subordinated his armed forces to his brother Gnaeus Cornelius Scipio Calvus so that he could go to Spain to conquer the Carthaginian territories there. He himself went back to Italy to organize the resistance against Hannibal.

swell

- Polybios, Historien 3, 42–43 ( Greek / English at PACE )

- Titus Livius 21, 26-28 ( online )

literature

- Klaus Zimmermann : Carthage - the rise and fall of a great power . Theiss-Verlag, Stuttgart 2010, ISBN 978-3-8062-2281-4 .

- Klaus Zimmermann: Rome and Carthage . 2nd revised edition, Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 2009, ISBN 978-3-534-23008-2

- Ursula Händl-Sagawe: The beginning of the 2nd Punic War. A historical-critical commentary on Livius Book 21 . Ed. Maris, Munich 1995, ISBN 3-925801-15-4 ( Munich works on ancient history 9. At the same time: Munich, Univ., Diss., 1992: A historical-critical commentary on Livius, book 21 ).

- Herbert Heftner : The Rise of Rome. From the Pyrrhic War to the fall of Carthage (280–146 BC). 2nd improved edition. Pustet, Regensburg 2005, ISBN 3-7917-1563-1 .

- Alfred Klotz : Appian's representation of the Second Punic War. Schöningh, Paderborn 1936.

- Karl-Heinz Schwarte: The outbreak of the Second Punic War - legal question and tradition. Steiner, Wiesbaden 1983, ISBN 3-515-03655-5 ( Historia Einzelschriften 43), (also: Bonn, Univ., Habil.-Schr., 1980/81).

- Sir Nigel Bagnall: Rome and Carthage - The Battle for the Mediterranean. Siedler, Berlin 1995, ISBN 3-88680-489-5 .