Battle of the Trebia

Coordinates: 45 ° 3 ′ 0 ″ N , 9 ° 36 ′ 0 ″ E

| date | December 18, 218 BC Chr. |

|---|---|

| place | Trebia river |

| output | Carthaginian victory |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

| Commander | |

| Troop strength | |

| 39,000 foot soldiers and 4,000 light riders | 20,000 foot soldiers, 6,000 heavy mounted men and less than 37 war elephants |

| losses | |

|

20,000 |

unknown, mainly Celts After the battle, many men and horses died of the cold, as did all but one of the elephants |

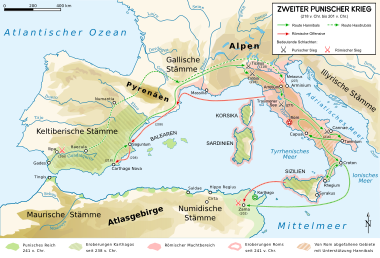

Saguntum - Lilybaeum II - Rhone - Ticinus - Trebia - Cissa - Lake Trasimeno - Ager Falernus - Geronium - Cannae - Nola I - Nola II - Ibera - Cornus - Nola III - Beneventum I - Syracuse - Tarentum I - Capua I - Beneventum II - Silarus - Herdonia I - Upper Baetis - Capua II - Herdonia II - Numistro - Asculum - Tarentum II - New Carthage - Baecula - Grumentum - Metaurus - Ilipa - Crotona - Large fields - Cirta - Zama

The Battle of Trebia was the second land battle of the Second Punic War between the armies of Carthage, under the leadership of Hannibal , and Rome under the command of the consul Tiberius Sempronius Longus in 218 BC. The battle of the Trebia ended with the first major defeat of Roman troops in the Italian heartland .

The events before the battle

Outbreak of the Second Punic War

After Carthage was defeated by the Romans in the First Punic War , but had subsequently expanded its power, a renewed conflict with Rome was inevitable. The Greek historian Polybios , who reproduces the Roman point of view, saw the expansion of Punic rule in Hispania as the establishment of a power base for a war of revenge against the Romans:

- “As soon as Hamilcar, with whose personal resentment united his and all Carthaginians' indignation at this rape, had fought down the rebellious mercenaries and secured peace and quiet in his hometown, his initiative immediately turned to Iberia, in order to get the resources there for the war against the Romans to win. And this is to be regarded as the third cause [for the later war], I mean the successes of Carthaginian politics in Iberia. Because trusting in the power they had gained there, they confidently went to war. "

It is unlikely that Carthage actually wanted war at this point. The Ebro Treaty between Hasdrubal and Rome in 226 BC BC, in which the Ebro was established as the border between Rome and Carthage, Polybius' view is refuted: Not Carthage, but Rome was looking for a pretext for a declaration of war. When the Barkide Hannibal conquered the city of Sagunt , located south of the Ebro , with which the Romans had recently allied contrary to the agreement, the Roman Senate changed its behavior and threatened Carthage with war if Hannibal did not extradite him immediately. The Romans wanted to act before Carthage regained power, and since they had just subdued the Gauls in the Po Valley, the time seemed right to them. So they submitted in 219 BC BC an unacceptable offer in the Carthaginian Council: “The Roman [Quintus Fabius] spoke, summarizing his toga in a depression: 'Here we bring you war and peace; take what you want! ' They answered these words no less defiantly with shouts that he should give them what he wanted. And when, on the other hand, by pouring out the depression, he declared that he was giving them war, they all replied that they would accept it and would lead it with the courage with which they would accept it. "

Hannibal's train through the Alps

When the war broke out, about 90,000 foot soldiers and 12,000 horsemen were available to Hannibal. He decided to forestall the Romans who were preparing to invade Africa by going on the offensive himself. Since the Roman fleet had ruled the sea since 241, Hannibal only had the land route available to attack Rome in Italy. In order to defend the conquered territories in Hispania, he left 10,000 infantrymen under Hanno in Hispain and sent another 10,000 to the threatened African homeland. He also carried 37 war elephants with him.

Historians are still not in agreement about the route he took, but it is believed that he first drew the Rhodanus (Rhône) and later the Isara (Isère) upstream. According to Polybius, he probably crossed the Alps via the Col de Clapier and descended to what is now Italy at the beginning of winter . Almost six months after he left Carthago Nova , around 38,000 foot soldiers, 8,000 horsemen, all 37 elephants, as well as 12,000 Libyans and 8,000 Spanish foot soldiers reached the Po Valley in November. Reasons for the overland route were, on the one hand, the dangers of seafaring, especially since the Roman fleet was far superior to Carthage's fleet after the First Punic War, as I said, and on the other hand, the surprise effect. In addition, Hannibal tried with success to win several Gallic tribes for himself. But around 9,000 Punians were also killed by land.

Roman tactics and battle of the Ticinus

→ Main article Battle on the Ticinus

|

Approximate location of the battlefield |

The Roman tactics provided for a double attack on Carthage-occupied Hispania as well as on the Carthaginian heartland on the North African coast. The attack on Hispania was led by Publius Cornelius Scipio (consul 218 BC) , who was already on the way to Spain with the fleet when he learned of Hannibal's crossing of the Rhône in Massilia . But despite his spies, Scipio was no longer able to place Hannibal in front of the Alps, whereupon he returned to Italy to find the Carthaginian in the Po Valley . The attack on North Africa was led by Tiberius Sempronius Longus, who broke off his preparations in Sicily when he reached Scipios and turned to the theater of war in northern Italy.

Of the two consuls, Scipio was the first to reach the Po , with a force of around 2,500 foot soldiers and 1,500 mounted soldiers, he met Hannibal and set up camp near the river Ticinus . From a chance meeting of the reconnaissance troops in November 218 BC it developed. The first battle. When the Punic associations attacked, the Roman spearmen fled and the Carthaginian cavalry surrounded the remaining legionaries, which were completely wiped out. Scipio was seriously injured in the battle and was allegedly only saved by the heroic intervention of his son .

After the defeat, Scipio Hannibal wanted to get out of the way as much as possible and wait for further reinforcements from Rome. But Sempronius, who came to help from Sicily, demanded a military decision in December 218 BC. Chr.

The battle

Starting position

The consul had taken a position near the fortress of Placentia , but had to leave it after Gaulish associations had been sighted and established himself on the hills behind the Trebia . The Carthaginian vanguard, which consisted mostly of Numidian horsemen, found only the abandoned camp and wasted time looting instead of pursuing the Romans.

They had now taken up their starting position and thus hindered Hannibal's march and forced him to set up camp on the other side of the river. Sempronius was already feeling safe, as his camp seemed protected by the Apennines on the left wing, the Po and the fortress Placentia on the right wing and the Trebia promised him an advantage in the attack of Hannibal in this particularly cold winter. The consul's army meanwhile comprised around 36,000 Roman infantrymen, 3,000 Gallic allies and 4,000 equites auxiliares (light cavalry auxiliaries). Scipio asked Sempronius to wait from his sick bed, but the consul was now in sole command as a result of Scipio's wounding and, knowing that his term of office would expire in a few months, pressed for a decision.

Hannibal, who was well informed through espionage, recognized this advantage, had all the villages that remained loyal to the Romans devastated and gave them victory in a cavalry battle. His army strength was around 20,000 foot soldiers (three fifths Libyans, two fifths Spaniards) and around 6,000 experienced cavalrymen.

The day of the battle

On the rainy and cold morning of December 18th, Hannibal's cavalry lured the Romans to their side of the river and engaged them in a battle. The impatient consul saw his cavalry in danger and sent his main army, still tired and deprived of morning meal, to fight. Hannibal, on the other hand, had his soldiers rubbed with fat and built campfires. In addition, he stationed his brother Mago with 1,000 Gallic riders and as many infantrymen through the dense forest, well camouflaged on his right side.

Meanwhile, the hungry, tired and soaked legionnaires were struggling to cross the ice-cold Trebia. The battle developed immediately, with the Carthaginians letting his elephants and cavalry attack the wings of the Romans, where their last mounted men were. These were completely wiped out and the Carthaginian horsemen now attacked the legionnaires. They knew that the retreat through the Trebia meant certain death and fought bitterly. But now Hannibal Mago gave the order to attack and let his troops attack the left side of the Romans from an ambush. The wings of the Romans and the last links of the center were broken up by this attack and panic set in. Nevertheless, the most capable legionaries managed to cut a swath through the Gallic mercenary associations on the left side of the Carthaginians, whereby about 10,000 Romans escaped to Placentia.

The ancient historians estimate the losses of the Romans at around 20,000 fighters, including many nobles and almost the entire cavalry. Nevertheless, the victory also cost the Carthaginians dearly. Not only did they lose the Gallic mercenary troops, but also many of the older and more experienced soldiers who died from their injuries or from the harsh cold. At the same time, diseases killed the war elephants except for one, on which Hannibal was in the spring of 217 BC. Rode to Arretium (Arezzo).

Consequences of the battle

The Battle of Trebia marked the beginning of a series of victories for Hannibal during his advance through Italy. The following year, when Gnaeus Servilius Geminus and Gaius Flaminius were consuls, the Romans suffered another heavy defeat in the Battle of Lake Trasimeno . At the same time, northern Italy was now in Hannibal's hands, who plundered cities like Arretium and thus brought panic to Rome.

literature

- Hans Delbück: History of the Art of War. Antiquity. Reprint of the first edition from 1900. Nikol Verlag, Hamburg 2003, ISBN 3-933203-73-2 .

- Theodor Mommsen: Roman history. (3rd book, 4th / 5th chapter). Weidmannsche Buchhandlung, 1869.

Web links

Individual evidence

- ^ John Peddie: Hannibal's War , Sutton Publishing, 1997, p. 57

- ↑ Polybios, Historíai 3, 10, 5-6.

- ^ Livy 21: 9, 3–11, 2.

- ↑ a b Polybios, Historíai 3, 33–56.

- ↑ In the Alps, hunting for Hannibal's trail . Stanford Report. May 16, 2007

- ^ Livy 20, 21-38.

- ↑ Polybios, Historíai 3, 45.

- ↑ Livy 21, 45, 1-3.

- ^ Livy 21, 39-46.

- ↑ Polybios, Historíai 3, 72.

- ^ Livius 21, 47–56.