Battle of Olustee

| date | February 20, 1864 |

|---|---|

| place | Olustee , Florida , USA |

| output | Confederate victory |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

| Commander | |

| Troop strength | |

| approx. 5,500 men, 16 guns | approx. 5,200 men, 12 guns |

| losses | |

|

1,861 (203 killed, 1,152 wounded, 506 missing) |

at least 946 (93 killed, 846 wounded, 6 missing) |

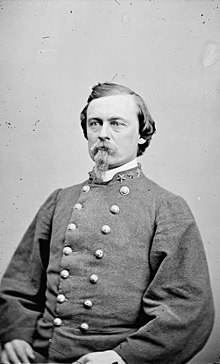

The Battle of Olustee, or Battle of Ocean Pond, took place at Olustee in East Florida on February 20, 1864 during the War of Civilization . After an expeditionary force of the US Army under General Truman Seymour had occupied parts of east Florida, they marched further inland to destroy a strategically important railway bridge. Near Olustee they met General Joseph Finegans and General Alfred H. Colquitt's Confederate troops .

The battle began as a face-to-face encounter in which both sides only had parts of their troops at their disposal. Seymour and Finegan strengthened their positions, with the Confederate succeeding in getting their units into position more quickly. This enabled them to outstrip the Northern line several times and take them under concentric fire. A first Confederate attack destroyed the left wing of the Union Army and led to the capture of five guns, but Seymour was able to form a second position thanks to reinforcement troops arriving in time and Confederate ammunition shortages. However, this was also outflanked and overrun by the Confederates, so that the Northerners had to retreat to Jacksonville . In doing so, they were not persecuted by the Confederates. The Confederate victory secured them possession of interior Florida until the end of the war. After the battle, several wounded black soldiers from the Union armies were murdered by the Confederates.

prehistory

Florida in the early years of the war

Florida was one of the first states to declare secession from the United States in 1861 and join the Confederate States . In the ensuing civil war, however, the state remained a sideline. It was sparsely populated, had little industry to speak of and little strategic value. The long coastline of Florida with its many estuaries and bays was both a curse and a blessing from a Confederate perspective. On the one hand, it made it more difficult for the US Navy to maintain its blockade of the Confederation. On the other hand, it was hard to defend against the superior strength of the Northern Navy. When General Robert Edward Lee took command of the Department of South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida ( Department of South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida ) in the fall of 1861 , he gave up the rigid defense along the coast and concentrated the troops in the hinterland, so that they can be pulled together and relocated more quickly if necessary. Florida's defenses were further weakened when the Confederate position in Central Tennessee and Kentucky collapsed in February 1862 as a result of the defeats at Mill Springs , Fort Henry and Fort Donelson . In response, the government withdrew almost all of its troops from Florida to reinforce Albert Sidney Johnston's army in northern Mississippi.

For the Union, for its part, Florida was particularly relevant in terms of maintaining the sea blockade . In March 1862, troops from the north occupied the coastal cities of Fernandina , Jacksonville and St. Augustine in the northeast of the country. The two golf ports Apalachicola and Pensacola followed in April and May. Since the Confederate defenders had been withdrawn, these conquests were usually bloodless and without a fight.

Not all of these cities were held permanently, however. The strategy of the Union Navy in Florida was based on occupying individual ports as bases and patrolling the rest of the coast from them and occasionally working into the hinterland from there. The war along the Florida coast in 1862 and 1863 was therefore characterized by small landing undertakings and raids , in which Union troops destroyed blockade breakers or salt works or briefly reoccupied cities. Jacksonville, for example, was evacuated in April 1862 but briefly occupied again in the fall of 1862 and spring of 1863. End of 1863 had the US Army in Florida five permanent garrisons: Fernandina and St. Augustine on the Atlantic coast were under Major General Gillmore Military District South ( Department of the South ) and hosted a total of about 2,300 Union soldiers. A similar number were stationed in Key West , Pensacola, and Charlotte Harbor and were part of Major General Banks ' Department of the Gulf . Opposite them were around 2,400 Confederates in General Gardner's Defense District in Central Florida and 1,300 in General Finegan's Defense District in East Florida. Both districts belonged to the military area of South Carolina, Georgia and Florida, which was under General Beauregard .

Planning the expedition

At the end of 1863 there was renewed interest in Florida on the part of the Union. On the one hand, the state had become more important in terms of the war economy. The Confederate States had lost large parts of their territory in 1862 and 1863, including many agriculturally important areas. The fall of Vicksburg and Port Hudson in July 1863 exacerbated this as it gave the northern states control of the entire Mississippi and cut off the eastern southern states from Texas. Florida became one of the most important food producers left in the south. Florida was of particular importance for supplying the armies with beef. In late 1863, supply officers from various southern armies vied to source meat for their armies in Florida. This development did not go unnoticed by the north: in December 1863, for example, the Union commander in Key West reported to his superior that, according to reports, 2,000 cattle were being transported from Florida to the Confederate armies every week. An offensive in Florida offered the opportunity to cut this flow of supply, either by bringing the agriculturally important areas directly under one's own control, or by at least destroying the state's railroad network.

Another reason for the northern states' increased interest in Florida was the recruitment of black volunteers. Blacks had been able to serve in the US Army since July 1862, and many slaves who had escaped their owners took advantage of this opportunity. General Gillmore's Defense Division South had played a pioneering role in this, and had been empowered to set up as many black regiments as he could find recruits in his Defense Division. Little defended by the Confederates, Florida, with its significant number of slaves, seemed a good place to find such recruits.

In addition, an offensive in Florida offered political prospects. US President Abraham Lincoln issued a proclamation on December 8, promising an amnesty. According to this, the United States would recognize the government of a breakaway state as legitimate if at least 10% of the 1860 electorate swore an oath of allegiance and elect a new government. Efforts were already being made in Arkansas and Louisiana, and there seemed to be potential in Florida too. Such re-admitted states promised to increase Lincoln's chances in the upcoming presidential election , both in the fight for the nomination of the Republican Party , as well as in the actual election.

General Gillmore wrote to General Halleck in Washington in December 1863 , presenting the military case for an offensive in Florida. Lincoln broadened the expedition's objectives, however, by sending his private secretary, John Hay, to Florida to collect the oaths of loyalty needed to restore a loyal government. He asked Gillmore for his support, as far as the military circumstances allowed. Lincoln communicated directly with Gillmore and passed both Secretary of War Stanton and Major General Halleck, the commander in chief of the US Army. Gillmore took up this and presented Secretary of War Stanton and Major General Halleck his plan to land on the west bank of the St. Johns River and from there to occupy Florida to Suwannee . To carry out this expedition he formed a mixed division under the command of Brigadier General Truman Seymour , which was embarked on their transport ships on February 6 in Hilton Head Island .

Landing and first forays into the interior

On the morning of February 7th, the Union fleet reached the Florida coast and headed up the St. Johns River to Jacksonville. The city had shrunk significantly after three years of war: instead of the 3,000 people counted in the 1860 census, only 25 families lived in the city, mostly women and children. The Confederates were taken by surprise when the Northerners landed. Although their scouts had noticed the activity of the US fleet, they could not find the target. For this reason, there was little resistance to the landing in Florida, apart from a few snipers, and the Northerners only took eleven prisoners.

The landing of the Union troops in Florida was reported to the Confederate Military District Commander Beauregard in Charleston on the same day, but Beauregard was faced with a difficult situation, because about the same time as the landing, activity broke out on the front in Charleston: Union General Alexander Schimmelfennig landed with one Division on John's Island, southwest of town. Beauregard correctly assumed that this was a diversionary maneuver, but could not be sure. Although he sent individual units to Florida and ordered the troops there to be concentrated, he kept Colquitt's brigade in reserve for the time being so that they could be thrown at Schimmelfennig if necessary. Thanks to this diversionary maneuver, Seymour's column in Florida remained outnumbered. While Seymour's expeditionary force comprised around 7,000 men, the Confederates had only gathered 700 men by February 10. Beauregard's orders to General Finegan, the Confederate Commander in East Florida, were therefore to offer only delayed resistance and to avoid open battle.

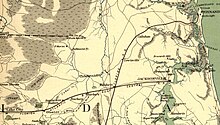

Seymour and his men meanwhile made their way into the interior of Florida to disrupt the Confederate lines of communication and to investigate the situation. On the afternoon of February 8, they left Jacksonville in three columns towards the St. Marys River some 55 km further west . The Union soldiers surprised two Confederate camps and were able to capture four guns and take some prisoners. On the morning of February 9, they reached the Baldwin rail junction , about 30 km from Jacksonville , where the Fernandina-Cedar-Key line and the Jacksonville-Tallahassee line met. The northern states were able to steal another gun and supplies worth half a million dollars here. However, Seymour had also hoped to confiscate a locomotive to power his advance westward over the railroad, but was disappointed here. Gillmore promised to remedy the situation and instructed him to advance further on the Suwannee.

Colonel Henry's Cavalry Brigade continued their advance on the morning of February 10th and reached Barber's Station before a skirmish broke out on St. Mary's River. The Confederate had destroyed the bridge over the river, but it could still be passed through. Henry's forces marched further west and reached Sanderson , about 30 km west of Baldwin , on the evening of February 10 . The next day they encountered Confederate infantry just outside Lake City . Around 600 men - Finegan's main force at that time - had lined up in the battle line. There was a firefight, but Henry found the Confederate line too strong, especially since he could not hope for support from infantry. His mounted brigade had advanced much faster and was now about 55 km from Seymour's infantry regiments. The supply situation for the advanced cavalry brigade was not easy either, so it was finally decided that Henry would retreat to Sanderson, where some infantry units were also marching. In retrospect, Henry Armed Forces was more than twice the size of Finegans, so he would probably have had a good chance of taking Lake City and moving on to Suwannee to destroy the railway bridge there.

Consolidation and renewed advance

In the days that followed, Gillmore wanted to consolidate his position in Florida. From his headquarters in Jacksonville, he first instructed Seymour to hold Sandersonville and then ordered him back to Baldwin. At the same time he ordered troops from St. Augustine in the direction of the St. Johns River. Overall, he wanted Florida along the Fernandina-Baldwin-Palatka-St. Occupy Augustine. In addition to Fernandina and St. Augustine, Baldwin, Jacksonville and Palatka were to be provided with small garrisons, for which he regarded 2,500 men as sufficient. In an army order, he offered the loyal people of East Florida protection from the US Army. He himself returned to his Hilton Head headquarters on February 14th. From the troops in Florida the military district Florida ( District of Florida ) was created, which he subordinated Seymour. He had meanwhile carried out other small raids, including to Gainesville and Callahan Station.

However, on February 17, Seymour suddenly changed his mind and wrote to Gillmore that he was planning an advance on Suwannee. On the one hand, he wanted to destroy the railway bridge there, on the other, he feared that the Confederates would otherwise have time to partially dismantle the railway line east of the bridge and use the rails elsewhere. It is unclear where this change of heart about Gillmore's intentions came from. Perhaps he was unsure of his own position in Florida and wanted to prevent the Confederates from sending reinforcements to Florida by destroying the railway bridge over the Suwannee, or was hoping that the destruction of the bridge would actually split Florida in two. He may also have been dissatisfied with his job in Florida and hoped a success would give his career a boost. It could also have played a role that he had received inaccurate information about the strength of the enemy and therefore assumed that he could defeat the Confederates without major problems.

Gillmore was not happy with Seymour's decision and immediately sent his chief of staff to Florida to end the offensive. However, the chief of staff was held up by weather problems and only reached Florida after the Battle of Olustee was over. Meanwhile, the Confederates in Florida had raised more troops. Thanks to intercepted reports from the Union troops outside Charleston, they now knew about the strength of Seymour's armed forces. By February 13, Finegan's army had grown to around 2,000 men, with whom he built field fortifications at Olustee. This was also due to the fact that Beauregard had exposed the Union's diversionary maneuver off Charleston as such: on February 11, he had his artillery open fire on Union troops on Morris Island in order to simulate an attack. In response, Schimmelfennig's division was withdrawn, and Beauregard was able to move Colquitt's brigade to Florida. By February 19, Finegan's armed force had grown to more than 5,000 men. Given the infrastructure in Florida, the rapid relocation of Colquitt's brigade was a logistical masterpiece. With no rail link between Georgia and Florida, the brigade had to take a train from Savannah, then march nearly 50 km to Madison, Florida, from where they could board the train to Olustee. At Olustee, Finegan had now taken a strong line that stretched from Ocean Pond on the left to a smaller lake on the right. Between these two bodies of water, Finegan's men had erected parapets of logs and earth. There was another small lake in front of Finegan's position on the left and a marshy bay on the right so that the position could not be attacked along its entire length.

course

Associations involved

union

The Union troops were Brigadier General Truman Seymour's expeditionary force. It was structured as follows:

| Barton's Brigade

Colonel WB Barton |

|

| Hawley's Brigade

Colonel JR Hawley |

|

| Montgomery's Brigade

Colonel James Montgomery |

|

| Cavalry Brigade

Colonel Guy V. Henry |

|

| artillery

Captain John Hamilton |

|

confederacy

The Confederate troops were under Brigadier General Joseph Finegans with Colonel RB Thomas as artillery commander. They belonged to the Defense District of East Florida and were structured as follows:

| 1st brigade

Brigadier General Alfred H. Colquitt |

|

| 2nd brigade

Colonel George P. Harrison |

|

| Cavalry Brigade

Colonel Caraway Smith |

|

| reserve |

|

Encounter battle

Seymour's division left Barbers Ford early that morning on February 20 and marched toward Lake City, with Colonel Henry's cavalry brigade in the lead. It was a clear, sunny morning, and a Union soldier later remembered the resinous scent of the pine forests through which the march passed. The Northerners made good progress, especially since the Confederate cavalry only offered sporadic resistance. This changed around 2:00 p.m.

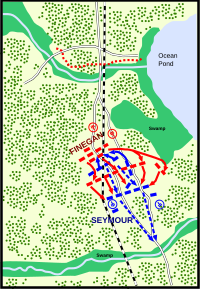

When Finegan heard of Seymour's approach, he had parts of Colonel Harrison's brigade and cavalry advance. These associations were supposed to skirmish with the Northerners and then lure them to the main Confederate position. However, he changed this when he learned that Seymour had only three regiments of infantry and some cavalry with him - misinformation that shows that both sides did not have a good overview of the units facing them. Finegan ordered General Colquitt and part of his brigade forward to make contact with the enemy, aided by a second and later a third wave. Overall, Finegan ordered the majority of his force from their fortifications to the front. The battle broke out about five kilometers east of Olustee. The area was level and overgrown with pine trees, behind which individual soldiers, but not entire groups, could find cover. A thickly overgrown, swampy bay followed to the north and west; apart from that, the bottom of the battlefield was solid and accessible.

On the Union side, however, Hawley's infantry brigade had also arrived, and two companies of the 7th Connecticut Infantry Regiment were sent forward in a skirmish line .

Confederate attacks

The skirmishers of the 7th Connecticut met the four regiments strong first wave of the Confederate and had to withdraw by an evasive maneuver . Meanwhile the rest of Hawley's brigade had formed, with the 7th New Hampshire Infantry Regiment on the left wing and the 8th US Colored Infantry Regiment on the right, and the Union artillery in between. But these units fared no better: Colquitt advanced with his four regiments, and his battle line outstripped the left wing of the Union troops. There was also a misunderstanding when setting up the 7th New Hampshire. The order of the regiment was lost and most of the men fled under Confederate fire. The inexperienced 8th US Colored Regiment managed to get into the battle formation. Because of its inexperience, it had to pay a high price afterwards. On the one hand, too much emphasis was placed on marching drill and too little on the use of weapons in the training of the men, so that they had little to counter the Confederate fire. They also lacked the instincts that more experienced units had, as Colonel Hawley explained after the war: “Old troops faced with such overwhelming odds would have run a little and got back into formation, with or without orders. The blacks stopped and were killed or wounded. ”In total, the regiment lost more than 300 of its 550 soldiers.

Reinforcements were added to both sides - the second and third waves of Confederate troops advanced from the fortifications by Finegan reached the battlefield, as did Barton's three-regiment Union brigade. Barton's Brigade took the position the 7th New Hampshire had vacated and extended it to the right. On the left wing, the 7th Connecticut was brought back into position, followed by the 8th US Colored. The Confederate line outstripped that of the Northern on both wings, leaving the Northerners exposed to a concentric fire. With the cavalry on both flanks and the infantry in the center, Colquitt let the Confederates advance.

The Confederate attack shattered the left wing of the Union line, which retreated, losing five guns. Two things, however, allowed Seymour's men a respite: First, the Confederates ran out of ammunition during their advance, which forced them to pause. On the other hand, Seymour's remaining infantry brigade, which consisted of two other black regiments, arrived at 4:00 p.m. This allowed Barton's brigade to withdraw. A new line with the 7th Connecticut in the center and the two black regiments was formed. However, this new line could not be maintained either: The Confederates had bypassed both the right and left wings of the northern states, thus again overlapping both wings and were able to maintain a devastating gunfire on Seymour's troops. The North Carolina 1st Infantry Regiment, for example, faced flank fire and lost 230 men. After the battle, the observers were full of praise for the fighting strength and steadfastness of the two black regiments, and indeed they had saved the Union from an even more severe defeat. But they could only moderate the eventual defeat, not avert it. The Confederates continued their attack across the board, throwing the Northerners from their positions; only the 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment was able to hold on, thereby delaying the Confederate advance, and then withdrawing in an orderly manner. Parts of the 7th New Hampshire also rallied for a battle of retreat, and eventually Henry's cavalry and 7th Connecticut were reared.

Black soldiers murdered

A particular concern of the Union forces on their retreat was how the Confederates would treat captured and wounded black soldiers and their white officers. The regimental doctor of the 8th US Colored insisted that black wounded be given priority in evacuating with ambulance vehicles, and when parts of the 54th Massachusetts found several wagons with the wounded on the march back, they pulled the wagons back to safety with ropes over the rails. The concerns of the Northerners were justified, because after the battle atrocities against black soldiers did indeed occur. It was not a massacre like the two months later after the battle at Fort Pillow , but post-war reports from Union and Confederation soldiers clearly show the existence of such incidents. Most of these atrocities appear to have been committed by Georgia soldiers. The number of victims can only be estimated, but was probably between 25 and 50. Around 70 black prisoners were taken to the Camp Sumter POW camp near Andersonville , where there was also isolated abuse, both against black soldiers and against their white officers.

aftermath

Seymour's troops withdrew relatively unmolested to the east and reached Jacksonville on February 22nd. To secure Jacksonville, Gillmore moved two more brigades to Florida for a short time, and the Confederates received further reinforcements. By the end of February, they had around 15,000 men in or out of Florida, now under the command of Major General James Patton Anderson . The military situation remained calm, apart from the occasional skirmish: the Northerners fortified their positions at Jacksonville and Palatka, while the Southerners holed up at Baldwin. When the main armies on both sides became active again in early spring, the troop concentration in Florida was quickly reduced. Most of Seymour's forces were transferred to Virginia in April, and the Confederates did likewise.

Olustee was a bloody defeat for the Union. Seymour recorded 1,861 dead, wounded and missing. The fallen also included Colonel Fribley, commander of the 8th U.S. Colored, and Lt. Col. William Nikolaus Reed of North Carolina 1st. The Confederates lost 946 men, 93 of them dead. The Union's losses are particularly high when you put them in relation to the troops deployed. Only an assault during the siege of Port Hudson resulted in greater relative losses.

The Confederate victory at Olustee secured the interior of Florida for the Confederates. Although the Union Army maintained its presence along the coast and carried out occasional raids inside, there were no more large-scale attempts at conquest. The state capital, Tallahassee , remained unoccupied until the end of the war, and supplies continued to be delivered to the southern armies. The military defeat of the Union also made it impossible for John Hay to collect the oaths of allegiance he needed for a political restoration of state government. He made one more attempt further south in Key West, and after unsuccessful there, too, he returned to Washington. Lincoln's administration has been harshly criticized as a result, on charges of sacrificing the health and lives of 2,000 soldiers in order to get three additional Florida delegate votes to the Republican National Congress in June. But there were also press voices that emphasized the importance of Florida's war economy. Conversely, after the heavy defeat at Chattanooga in autumn 1863, Olustee gave the southerners a much-needed glimmer of hope.

Commemoration

The battlefield became the first official Florida State Historic Site in 1912 and has been on the National Register of Historic Places since August 1970 . Today it is a state park as the Olustee Battlefield Historic State Park , which also includes a visitor center. A battle re-enactment is also held there every February .

Remarks

- ↑ OR Series 1, Volume 35, Part 1, p. 288

- ↑ OR Series 1, Volume 35, Part 1, 331

- ^ Baltzell, The Battle of Olustee (Ocean Pond), Florida , p. 220

- ↑ Baltzell, The Battle of Olustee (Ocean Pond), Florida , p. 221. The losses of the Confederate cavalry are missing here

- ^ Nulty, Confederate Florida , pp. VII, pp. 20, p. 24, p. 33

- ↑ Steven E. Woodworth, Jefferson Davis and his Generals , pp. 70, 85 and 90

- ^ Shelby Foote, Fort Sumter to Perryville , pp. 352f.

- ↑ Nulty, Confederate Florida , pp. 42–42.

- ↑ See the strength reports of the Defense Division South of December 31, 1863, Official Records, Series 1, Volume 28, Part 2, p. 136 and of the Defense Division Golf of the same date, Official Records, Series 1, Volume 26, Part 1, p. 892 and p. 895f.

- ↑ South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida Military Area Strength Report as of December 31, 1863, Official Records, Series 1, Volume 28, Part 2, p. 601

- ^ Nulty, Confederate Florida , pp. 61-67

- ↑ Broadwater, The Battle of Olustee , 1864, p. 10

- ↑ Nulty, Confederate Florida , pp. 54-57

- ↑ Broadwater, The Battle of Olustee , 1864, pp. 10ff.

- ^ Nulty, Confederate Florida , p. 71

- ↑ Broadwater, The Battle of Olustee , 1864, pp. 12ff., P. 15

- ^ Nulty, Confederate Florida , pp. 72–72.

- ↑ Broadwater, The Battle of Olustee , 1864, p. 19

- ^ Foote, Fredericksburg to Meridian , p. 900

- ^ Nulty, The Road to Olustee , pp. 79-82

- ^ Nulty, Confederate Florida , pp. 82-85

- ↑ Broadwater, The Battle of Olustee , p. 32f.

- ^ Nulty, Confederate Florida , p. 86

- ^ Nulty, The Seymour Decision , 300ff.

- ↑ Nulty. Confederate Florida , pp. 94f.

- ^ Nulty, The Seymour Decision , pp. 302-2.

- ↑ Nulty, Confederate Florida , 99f., Broadwater, The Battle of Olustee , pp. 51f.

- ↑ Nulty, Confederate Florida , pp. 101f., 105f., 113f.

- ^ Nulty, The Seymour Decision , pp. 308-311

- ^ Nulty, The Seymour Decision , pp. 312f., Foote, Fredericksburg to Meridian , 902f.

- ↑ Broadwater, The Battle of Olustee , p. 70

- ^ Nulty, Confederate Florida , p. 115

- ↑ Broadwater, The Battle of Olustee pp. 57f.

- ^ Nulty, Confederate Florida , pp. 107-119

- ↑ Broadwater, The Battle of Olustee , pp. 65f.

- ↑ The structure basically follows Seymour's information in his loss report, OR Series 1, Volume 35, Part 1, p. 298 , for the number of guns see Nulty Confederate Florida , p. 124. Seymour differentiated in his report between Bartons and Hawley's "Brigades" and Montgomery and Henry's "commandos", but Nulty also refers to these as brigades throughout.

- ↑ From this regiment the 35th US Colored Infantry Regiment was formed on February 8, 1864, NPS: Battle Unit Details , accessed on April 18, 2020

- ↑ Baltzell, The Battle of Olustee (Ocean Pond), Florida , p. 210

- ^ Nulty, Confederate Florida , pp. 124f., P. 175

- ^ Rory T. Cornish, "To Irish Confederate: Brigadier General Joseph Finegan of Florida" in Confederate Generals in the Western Theater , Volume 3, ed. by Lawrence Lee Hewitt and Arthur W. Bergeron Jr., University of Tennessee Press, 2011, here p. 200. Cornish mentions only one cavalry regiment, but according to Boyd, The Federal Campaign of 1864 in East Florida , p. 18, both were deployed .

- ^ Nulty, Confederate Florida , pp. 129ff.

- ↑ Broadwater, The Battle of Olustee , p. 79

- ↑ Joseph R. Hawley, Comments on General Jones's Paper , in: Battles and Leaders of the Civil War , pp. 79f., Here p. 80, Nulty, Confederate Florida , pp. 132-137, 142-145

- ^ Nulty, Confederate Florida , pp. 145, 148

- ↑ Boyd, The Federal Campaign of 1864 in East Florida , pp. 24–24.

- ↑ Nulty, Confederate Florida , pp. 153–15.

- ↑ Nulty, Confederate Florida , pp. 167–167. However, thanks to Finegan's precautions, this ammunition shortage lasted only 20 minutes, see Rory T. Cornish, "To Irish Confederate: Brigadier General Joseph Finegan of Florida," in Confederate Generals in the Western Theater , Volume 3, ed. by Lawrence Lee Hewitt and Arthur W. Bergeron Jr., University of Tennessee Press, 2011, here p. 202. The guns captured by the Confederates were three Napoleon twelve-pounder grenade cannons and two Parrott-type rifled ten-pounder cannons, see OR, Series 1, Volume 35, Part 1, p. 342

- ^ Nulty, Confederate Florida , pp. 158, p. 165

- ↑ J. Matthew Gallman. "In Your Hands That Musket Means Liberty: African American Soldiers and the Battle of Olustee." In Wars within a War: Controversy and Conflict over the American Civil War , ed. by Joan Waugh and Gary Gallagher. University of North Carolina Press, 2009, doi : 10.5149 / 9780807898444_waugh here p. 102f.

- ^ Nulty, Confederate Florida , pp. 165ff.

- ↑ David J. Coles, "Shooting Niggers, Sir": Confederate Mistreatment of Black Soldiers at the Battle of Olustee ". In Black Flag Over Dixie: Racial Atrocities and Reprisals in the Civil War , ed. by Gregory JW Urwin. Southern Illinois University Press, 2004, pp. 65-88; Bergeron, The Battle of Olustee , pp. 144f .; J. Matthew Gallman. "In Your Hands That Musket Means Liberty: African American Soldiers and the Battle of Olustee." In Wars within a War: Controversy and Conflict over the American Civil War , ed. by Joan Waugh and Gary Gallagher. University of North Carolina Press, 2009, here 104f .; For the origin of the perpetrators from Georgia, see Rory T. Cornish: "To Irish Confederate: Brigadier General Joseph Finegan of Florida" in Confederate Generals in the Western Theater , Volume 3, ed. by Lawrence Lee Hewitt and Arthur W. Bergeron Jr., University of Tennessee Press, 2011, here p. 202f.

- ↑ Nulty, Confederate Florida , pp. 181–18.

- ↑ Nulty, Confederate Florida , pp. 187–194, 201

- ↑ Broadwater, The Battle of Olustee , 180

- ↑ Baltzell, The Battle of Olustee (Ocean Pond), Florida, pp. 220f.

- ^ Thomas L. Livermore, Numbers and Losses of the Civil War , Boston & New York, 1900, p. 75

- ↑ Broadwater, The Battle of Olustee , p. 4

- ^ Foote, Fredericksburg to Meridian , p. 906

- ^ Nulty, Confederate Florida , p. 216

- ^ Rory T. Cornish, "To Irish Confederate: Brigadier General Joseph Finegan of Florida" in Confederate Generals in the Western Theater, Volume 3, ed. by Lawrence Lee Hewitt and Arthur W. Bergeron Jr., University of Tennessee Press, 2011, here p. 203

- ^ Olustee Battlefield in the National Register Information System. National Park Service , accessed May 2, 2020.

- ↑ Olustee on Florida State Parks website, accessed April 26, 2020

- ^ Website of the Olustee Festival , accessed April 26, 2020

literature

- George F. Baltzell: The Battle of Olustee (Ocean Pond), Florida. In: The Florida Historical Quarterly. 9, 1931, pp. 199-223.

- Arthur W. Bergeron, Jr .: The Battle of Olustee. In: John David Smith (ed.): Black Soldiers in Blue: African American Troops in the Civil War Era. University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill 2002, ISBN 0-8078-2741-X , pp. 136-149.

- Mark F. Boyd. The Federal Campaign of 1864 in East Florida: A Study for the Florida State Board of Parks and Historic Monuments. In: The Florida Historical Quarterly 29, 1950, pp. 1-37

- Robert P. Broadwater: The Battle of Olustee, 1864: The final Union attempt to seize Florida. McFarland, Jefferson, NC / London 2006.

- Shelby Foote : The Civil War: A Narrative. Vol. 2: Fredericksburg to Meridian. First vintage edition. Vintage Books, New York 1986.

- James M. McPherson : The Atlas of the Civil War. Courage Books, Philadelphia 2005, ISBN 0-02-579050-1 , p. 147.

- William H. Nulty: The Seymour Decision: An Appraisal of the Olustee Campaign. In: The Florida Historical Quarterly. 65, 1987, pp. 298-316.

- William H. Nulty: Confederate Florida: The Road to Olustee. University of Alabama Press, Tuscaloosa 1994, ISBN 0-8173-0473-8 .

- United States War Department: The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Govt. Print. Off., Washington