Battle of Kyzikos

| date | 410 BC Chr. |

|---|---|

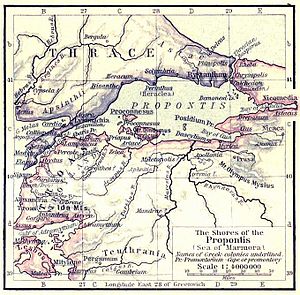

| place | Marmara Sea , today Turkey |

| output | Athens wins |

| consequences | Athenian offensive on the Bosporus , extension of the Peloponnesian War |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

| Commander | |

|

Alkibiades ; |

Mindaros †, Hippocrates , Hermocrates , Klearchus ; |

| Troop strength | |

| 86 ships; Hoplites , Sagittarius |

60 to 80 ships; Land forces, Persian mercenaries |

| losses | |

|

about 40 ships captured |

Total loss of the fleet |

Sybota - Potidaia - Spartolus - Stratos - Naupactus - Plataea - Olpai - Tanagra - Pylos - Sphacteria - Corinth - Megara - Delion - Amphipolis - Mantinea - Melos - Syracuse - Miletus - Syme - Eretria - Kynossema - Abydos - Kyzikos - Ephesus - Chalcedon - Byzantium - Andros - Notion - Mytilene - Arginus - Aigospotamoi

The Battle of Kyzikos was a combined sea and land battle during the Peloponnesian War . It was born in 410 BC. Chr. Between the fleets of Athens and Sparta before Cyzicus in the Propontis discharged. Troops of the Persian Empire also intervened in the subsequent land struggle . The battle ended in a clear defeat for the Spartans, whose fleet was completely destroyed.

The starting point

After losing its expedition fleet in Sicily (413 BC), Athens fought to keep its Attic empire in the Aegean . In the first year after the catastrophe, Sparta, as the dominant power of the Peloponnesian Confederation, managed to win over numerous cities and islands, including Chios , Miletus , Euboia and the most important cities on the Hellespont and Bosporus straits . This was also made possible thanks to an alliance and subsidy treaty with the Persian Empire , through which the Peloponnesians were able to equip a large fleet.

After the first signs of disintegration, Athens reacted and set up a new fleet with which it faced the Spartans on the Hellespont, whose control was indispensable for the Athenian grain imports from the Black Sea . In the strait between Abydos and Sestos it was the Attic generals Thrasybul and Thrasyllos 411 BC. BC succeeded in putting the Spartan sea lord Mindaros in place in two naval battles. In the first, the Battle of Kynossema , the Athenians had only slight advantages. In the second, the Battle of Abydos , the result was clearer and the Spartan fleet, which included strong contingents from Syracuse , Chios and Corinth , lost 30 ships. Despite these setbacks, the Mindaros' fleet remained a threat, as the higher wages of the Spartans ensured that they were never short of rowers, while replacements for the lost ships were soon built with the wood of the great king.

The return of Alcibiades

The decisive factor in the naval battle of Abydos was the surprising intervention of the general Alkibiades , who had been accused of religious offenses during the Sicily expedition and who had evaded the impending trial by fleeing to Sparta. Alcibiades was in Spartan service in 412 BC. Was the driving force behind the defection of Chios and Miletus, but soon afterwards he tried to thwart the Spartan-Persian alliance by advising Tissaphernes , the satrap of Lydia, not to let Sparta become too strong and instead, playing off the two leading powers of Greece against each other. Before the Spartans saw through his machinations, he had at the beginning of 411 BC. Chr. Changed sides again, soon to campaign again vigorously for the interests of Athens.

After the naval battle of Abydos, Alkibiades first made one last attempt to convince his friend Tissaphernes of an alliance with Athens. The latter, however, had received new instructions from the great king Dareios II and had him arrested and locked up in Sardis . After thirty days, Alcibiades managed to escape. In an adventurous ride he reached Klazomenai on the Ionian coast. From there he drove with 5 triremes and a light boat to the Hellespont again, where he found only 40 Athenian ships, since the others had sailed under Thrasybul to claim the tribute on the nearby islands.

The approach

Mindaros had 60 ships left after the Battle of Abydos, with which he went to Kyzikos on the north coast of Asia Minor to solicit new aid from Pharnabazos , the Persian satrap of Phrygia . The current preponderance of the Spartans was short-lived. With the return of Thrasybul from Thasos and the simultaneous arrival of the strategist Theramenes with 20 new triremes from Athens, the balance of power shifted again in favor of the Athenians. The associated surge of fresh optimism was reinforced by the longed-for news from Theramenes that after the oligarchic coup at the beginning of the year, Athens had returned to the democratic state constitution.

When he learned that Mindaros and Pharnabazos had occupied the unfortified Kyzikos, Alkibiades, who were now superior in strength, immediately took up the pursuit. The Athenians set out from Sestos in the dark of the night, so that in the opposite Abydos one could not see the number of passing ships. A ban on crossing over to the opposing coast was intended to additionally secure the element of surprise, violating the threat could result in the death penalty. From Sestos the Athenians first drove to Parion and then to the island of Prokonnesos in the Propontis . The following morning, Alkibiades gave a speech to the crews in which he tried to make the upcoming battle palatable to the soldiers by means of the expected booty:

"We have no money, but the enemies have it in abundance from the Great King."

From Prokonnesos the Attic fleet drove in a south-easterly direction past the coast of the Arktonnesos peninsula to Kyzikos. It rained during the journey, but when we arrived in front of the city it suddenly cleared and the sun lit up the scenery in the bay in front of the harbor, where Mindaros was holding a naval maneuver. With him were his vice-admiral Hippocrates , the strategist Klearchus and the Syracuse general Hermocrates as leaders of the Sicilian contingent.

Topography and source criticism

The historian Xenophon says only a few words about the ensuing naval battle, while the biographer Plutarch , who wrote five centuries later, describes it as a very simple operation: Alkibiades drove past the enemy with only 20 ships and when they took up the chase, Thrasybul appeared and Theramenes with the rest of the fleet and cut them off from retreating to port.

A look at the map reveals, however, that this could not have been so easy, as Kyzikos was located on the isthmus that connects the Arktonnesos peninsula with the mainland of Asia Minor. To the west as to the east, the coasts of the peninsula in the north and Phrygia in the south form an acute angle, at the end of which there was a deeply incised bay of Kyzikos, with a promontory in the north-west near the town of Artake narrowing the entrance. The city was not fortified at the time, which is why the Peloponnesians and Pharnabazos took it without any problems. It was protected from the mainland by a short canal that connected the western gulf with the eastern one. Because of this canal, Kyzikos had three harbors, one in the west, one in the east and a third basin in the middle of the isthmos, which could only be reached through the canal.

It was therefore impossible to simply pass through the city, and confirmation can be found in the third surviving source, the historian Diodorus , whose report may appear confusing without taking the topographical facts as a basis, but after a precise comparison it can be understood as an articulate representation of a complex battle event. Otherwise, the quality of Diodor’s work varies. It is generally said that Diodorus is as good as his sources. In the case of the Battle of Kyzikos, he apparently had a very detailed battle analysis at his disposal, which is why his report is preferred by military historians to the other traditions.

Bruno Bleckmann takes a different view , according to which Diodorus relied on material that, mediated via an intermediate source, ultimately rests on a basic source that Bleckmann identifies with Theopompos . According to Bleckmann, the representation of Theopompus was characterized by the fact that he took over material from Xenophon, changed it and expanded it with fictitious elements. Due to the numerous additional, topographically exact information from Diodorus, the theory of such a subordinate construction of the battle report of Kyzikos is not convincing. Overall, Bleckmann's argument suffers from the fact that he largely limits himself to pure source criticism, without any serious attempt to reconstruct the course of the battle. On the other hand, John Francis Lazenby undertakes one of these, but fails in the land battle due to an erroneous assumption regarding the position of Chaireas.

The naval battle

Diodorus reports that before the sea battle began, the Athenians disembarked their hoplites under the command of Chaireas in the territory of the Cyclists. The first question to be asked is where this disembarkation took place. Only the Arktonnesos peninsula can be considered the territory of the city of Kyzikos, not the other Phrygian opposite coast. The approach of the Attic fleet was from the northwest along the coast of the peninsula. Taking into account the basic military rule that the fleet and land troops marched as parallel as possible, disembarkation was therefore only practicable on the southwest coast of Arktonnesos. The natural harbor of Artake behind the promontory of the same name appears to be an ideal place not far from Kyzikos.

From Diodor's depiction it can be concluded that the Attic fleet command must have had a precise idea of the local conditions and a clear plan before the start of the battle. Taking all the circumstances into account, it is therefore likely that the Athenians initially stayed behind the Artake promontory in order to unload their land troops there and study the situation from the hill dominating the bay. It is even conceivable that they set up a signal post on the foothills to coordinate the movements of the various parts of the navy and army.

What followed was a combined operation on land and sea, in which Chaireas was given the task of attacking the city with his land troops, while Alkibiades and his squadron lured the Peloponnesian fleet away from it. The ancient sources agree that he drove ahead with 20 triremes. Two other squadrons under the command of Thrasybul and Theramenes initially stayed behind the promontory to allow the Spartan ships to retreat to the port at the appropriate moment.

After he had circled the promontory, Alkibiades perhaps steered for a while parallel to the land troops advancing hidden inland, but as soon as the Spartans noticed his approach, he took flight in mock surprise to escape across the bay in the southwest. Misunderstanding the situation, Mindaros gave the order to pursue the supposedly defeated enemy. According to Xenophon, he had 60 triremes like the last one in Abydos, but possibly he had found and manned more boats in Kyzikos, since Diodorus speaks of 80 ships.

After the two fleets had moved a certain distance from the city, the ships of the Alcibiades turned surprisingly. The reason for such daring revealed when it was noticed on the Spartan ships that two more naval formations were appearing behind the foothills of Artake. Theramenes had also entered the bay of Kyzikos with his ships to relocate the Peloponnesians from the east to retreat into the port, and Thrasybul closed the gap between the two wings of the Attic fleet, coming directly from the north. Surrounded on three sides, the Spartans fled in the only direction left to them, south, where they beached their ships on the nearby coast.

The land battle

Mindaros landed on the coast in the southwest of Kyzikos. Nearby was the place Kleroi, where Pharnabazos had assembled his army. At first there was a battle for the ships on the bank. The Athenians tried to pull them back into the water with grappling hooks. When this was unsuccessful because of enemy resistance, Alkibiades also went ashore west of the Spartans to attack Mindaros from both land and sea. Thrasybul, meanwhile, landed with the riflemen on the eastern flank of the enemy in order to move them to retreat to Kyzikos on land. Mindarus himself opposed Alcibiades and sent his subordinate Klearchus against Thrasybul. The troops of Thrasybul, pressed from all sides, soon found themselves in a difficult position against the simultaneous attack of Clearchus and a quickly rushed unit of Persian mercenaries. Thrasybul thereupon gave the order to Theramenes to unite with the troops of Chaireas and then to bring help.

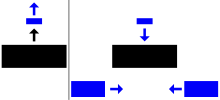

The position of Chaireas at this point in the battle is initially a minor mystery. Presumably, as planned, he had reached Kyzikos from the northwest. In the city, which and its ports stretched like a bolt across the isthmus, his advance became more difficult. There was no city wall, but if a bridge over the canal was not found, the route to battle would be blocked. The fact that Thrasybul, although severely distressed and in urgent need of help, gave Theramenes the order to drive back first to reunite with Chaireas seems in this light to be a clear indication of the solution to the problem. Apparently Chairea needed help to cross the canal. It is conceivable, for example, that Theramenes improvised a ship bridge with his triremes , which enabled the hoplites to reach the battle.

After this almost fatal delay, Thrasyboul was saved by the arrival of the Hoplites of Chaireas and the fresh forces of Theramenes, who fell on the flank of the Persian mercenaries and after these also put the Spartans of Klearchus to flight. They then fell in the back of Mindaros. He tried to counter the threat by dividing his forces again, but the troops, exhausted by the hard defensive battle against Alcibiades, were no longer able to cope with the double burden. After Mindaros ended his life fighting heroically, the Peloponnesians abandoned the boats and fled into the nearby mountains. Only the Syracusans were quick enough to set fire to their ships before escaping with the others to the camp of Pharnabazos.

The result

The Athenians captured the entire fleet of the Spartans and pulled the boats that were still buoyant, around 40 triremes, back into the water. As Pharnabazos brought his remaining infantry and a large number of horsemen from the mountains, they immediately set out to sea and drove to the nearby island of Polydoros, where they erected two victory monuments, one for the sea battle and one for the land battle. The next day they occupied the city of Kyzikos, abandoned by the Peloponnesians, which offered no resistance. The Peloponnesian naval command, which was now in the hands of Hippocrates, sent a report to Sparta, which was intercepted by the Athenians and often mocked, since their expressed despair was felt to be exemplary of the laconic style of the Spartans:

“Boats lost. Mindaros dead. Men are hungry. Don't know what to do. "

The assessment

The battle of Kyzikos was generally considered to be the greatest achievement of Alcibiades. The bold conception, the articulated plan, the perfect execution and the clear result established his reputation as a brilliant strategist, who from now on was trusted to do almost everything. Modern historians have therefore compared the battle with Napoleon's triumph in the Battle of Austerlitz , especially since in both cases the sun seemed to herald victory.

The assessment of the battle has revolved around the question of the authorship of the victory since antiquity, with Xenophon already trying to emphasize the role of Alcibiades, while the source of Diodors ascribes the success more to a "collective effort of the three strategists" Alkibiades, Thrasybul and Theramenes.

If you take Diodor's report seriously, it actually shows an extremely complex and interlocking approach by all those involved. In addition to the ability to coordinate, luck and improvisation may have played a role as well as the difficult to understand inactivity of the Persians, which is not only observed here. Nevertheless, the battle of Kyzikos shows the Attic naval command obviously at the peak of its capabilities.

In the end, this evaluation must not overlook the contribution of Chaireas, which is hardly noticed by most historians, but whose march over all the obstacles around the bay was highly remarkable and ultimately decisive. The bold plan of Alcibiades, the self-sacrifice of Thrasybul, the improvisational art of Theramenes and the boots of Chaireas were the elements that helped secure the victory of the Athenians at Cyzicus. Each of the four commanders has therefore honestly earned its share of the fame through individual efforts.

The consequences

The unexpected victory of Kyzikos was celebrated in Athens with extensive sacrifices. Sparta responded to the elimination of its fleet by offering, through its ambassador Endios, a peace based on the status quo . The leaders of the oligarchs were in favor of the proposal, but Cleophon , the leader of the Populares, persuaded the popular assembly to reject it.

The Athenians then equipped another 30 ships, which were sent with 1000 hoplites and 100 riders under the command of Thrasyllos to recapture Ionia , but after the defeat of Ephesus also joined the fleet on the Hellespont. With these reinforcements Alkibiades went from the winter of 409/08 BC. On the offensive to recapture the lost positions on the straits. He succeeded in repeating the miracle of Kyzikos several times, for example in the second battle of Abydos and in the battle of Chalcedon , but especially thanks to his heroic efforts in the storming of Selymbria and Byzantium . As Alcibiades after seven years of absence in the summer of 408 BC When he finally returned home, the Athenians gave him a triumphant reception.

With the conquest of Byzantium, Athens had regained control over the straits, which was vital for the city, as it was dependent on grain imports from the Black Sea region. The income from the Sund tariff also improved the tense financial situation of the Athenians, so that they were able to hold out the war effort for several years. The most important goal, the breaking up of the alliance between Sparta and the Persian Empire, was not achieved.

The end

After the loss of the ships, Pharnabazos in particular encouraged the Spartans to use new armaments by providing the necessary wood and the necessary subsidies. The Spartan leadership transferred the supreme command of the fleet to Pasippidas, who requested new triremes for the shipless crews from the allies, and then to Kratesippidas. Since the Spartan constitution prescribed an annual change in the office of the Spartan sea lord, it followed in 407 BC. The still undescribed Lysander , who negotiated an increase in pay with the Persian prince Cyrus and soon again had 90 ships at his disposal. Against the patient tactician Lysander, the undisputed talent of Alcibiades proved ineffective. The myth of Cyzicus could no longer be replicated, although ambitious subordinates might try. After Antiochus, the helmsman of Alcibiades, lost his life and a number of ships at the Battle of Notion, despite orders to the contrary in clumsy imitation of the successful strategy of Cyzicus, the people of Athens brought the people in command to account. Now the fame of Cyzicus suddenly turned out to be a burden: awaiting miracles from Alkibiades, the Athenians were unwilling to forgive the smallest mistake and put it down.

After a year later the best of his successors were sentenced to death for failure to provide assistance in victorious battle , the third garrison of the Attic naval command lost the fleet and empire in the unfortunate battle of Aigospotamoi (405 BC). Alkibiades had seen the catastrophe coming: despite his exile, on the eve of the battle he had ridden to the commanding commanders on the Hellespont to suggest a better strategy, but they had only laughed at him. After the loss of its fleet at Aigospotamoi, the Attic Empire was lost and Athens surrendered after a brief siege. The battle of Kyzikos had only extended his agony by six years and many thousands of deaths.

literature

- Antony Andrewes: Notion and Kyzikos: The Sources Compared . In: The Journal of Hellenic Studies . Volume 102, 1982, pp. 15-25.

- Bruno Bleckmann : Athens' path to defeat. The last years of the Peloponnesian War . Teubner, Leipzig / Stuttgart 1998. ISBN 3-519-07648-9 .

- Donald Kagan : The Peloponnesian War . New York 2003.

- Peter Krentz: Athenian Politics and Strategy after Kyzikos . In: The Classical Journal . Volume 84, No. 3, February-March 1989, pp. 206-215. [1]

- John Francis Lazenby: The Peloponnesian War: a military study . London, New York 2004, pp. 202-206. [2]

- Robert J. Littman: The Strategy of the Battle of Cyzicus . In: Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association . Volume 99, 1968, pp. 265-272. [3]

- Lawrence A. Tritle: A new history of the Peloponnesian War . Oxford et al. a. 2010.

- Karl-Wilhelm Welwei : Classical Athens. Democracy and Power Politics in the 5th and 4th Centuries . Primus-Verlag, Darmstadt 1999, ISBN 3-89678-117-0 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Thucydides , VIII 1-96.

- ↑ Thucydides, VIII 97-109; Xenophon , Hellenika , I 1,1-8; Diodor , Bibliothek , XIII 38-42 and 45f.

- ↑ Thucydides, VI 53 and 88-93, VIII 12-37, 45-59 and 81f; Xenophon, Hellenika , I 1,5f; Plutarch , Alkibiades , 17-27.

- ↑ Xenophon, Hellenika , I 1,9f; Plutarch, Alkibiades , 27f.

- ↑ Xenophon, Hellenika , I 1,11f; Diodor, Library , XIII 49; Plutarch, Alkibiades , 28.

- ↑ Xenophon, Hellenika , I 1,13-15; Diodor, Library , XIII 49; Plutarch, Alkibiades , 28.

- ↑ Xenophon, Hellenika , I 1.16; Plutarch, Alkibiades , 28.

- ↑ Xenophon, Hellenika , I 1.16; Plutarch, Alkibiades , 28.

- ^ Diodorus, Bibliothek , XIII 50f. See, for example, John Francis Lazenby: The Peloponnesian War: a military study , pp. 203-205.

- ^ Bleckmann, Athens way in the defeat , pp. 56–72.

- ^ John Francis Lazenby: The Peloponnesian War: a military study , pp. 203-205.

- ^ Diodorus, Bibliothek , XIII 49,6.

- ↑ But it is also conceivable that Alkibiades led up to 40 ships, as this corresponded to Mindaro's known naval strength of the Athenians, so that such a number was less likely to arouse suspicion.

- ↑ Diodor, Bibliothek , XIII 50,1f; see. Xenophon, Hellenika , I 1.18.

- ↑ Xenophon, Hellenika , I 1.16; Diodorus, Library , XIII 50.2.

- ↑ Xenophon, Hellenika , I 1,17f; Diodor, Library , XIII 50; Frontinus , Strategemata , II 5.44; Plutarch, Alkibiades , 28. See John Francis Lazenby: The Peloponnesian War: a military study , pp. 203f.

- ↑ The order of Thrasybul seems absurd at first sight, since it had to lead to Theramenes leaving. If, in spite of his difficult situation, Thrasybul refrained from calling for immediate help, there must be a weighty reason for it.

-

↑ There are of course other ways and solutions for the introduction of the hoplites conceivable. In any case, however, it seems that the help of Theramenes was necessary, since this is the only way to explain Thrasybul's order.

Antique ship bridge

Antique ship bridge - ↑ The Hoplites of Chaireas rolled up the enemy line from their right flank, first the Persian mercenaries, then Klearchus and finally Mindaros. Xenophon, Hellenika , I 1,17f; Diodor, Library , XIII 51; Plutarch, Alkibiades , 28.

- ↑ Xenophon, Hellenika , I 1,18-23; Diodor, Library , XIII 51; Plutarch, Alkibiades , 28.

- ↑ Cf. Bleckmann, Athens Weg in die Niederlage , pp. 67–74, quotation p. 68.

- ↑ Diodor, Bibliothek , XIII 52f; Plutarch, Alkibiades , 28.

- ↑ Xenophon, Hellenika , I 2.1-4.20; Diodor, Bibliothek , XIII 52 and 64-69; Cornelius Nepos , Alkibiades 5f; Plutarch, Alkibiades , 29-33.

- ↑ Xenophon, Hellenika , I 3.13 and 4.1–7.

- ↑ Xenophon, Hellenika , I 1.24-26 and 32, 4.1-7. On the parallels between the various battles, see Bleckmann, Athens Weg in die Deflage , p. 64.

- ↑ Xenophon, Hellenika , I 7.1–34 and II, 1.1–32.