Skokomish

The Skokomish , now more commonly called Twana , are an Indian tribe living in the west of the US state Washington . They speak a dialect of the southwestern coastal Salish , the Twana dialect, but they also share cultural features with the inland tribes.

The Skokomish were one of nine separate groups linked by a common land, similar cultural features, and the Twana language. They are the original inhabitants of the villages on the Skokomish River and its northern fork. Today they live along the Hood Canal , a fjord west of Puget Sound .

The name Skokomish comes from the Chinook and the Lushootseed and means "people of the great river" (skookum (great river), -mish (people, people)). The name Twana probably means "people at the bottom" or "people at a portage".

history

Traditional area

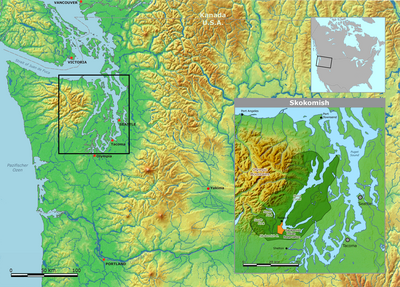

The land of the Twana comprised an estuary and its catchment area, which is now called the Hood Canal , plus the adjacent coastal strip. It covered large parts of today's Jefferson , Mason and Kitsap counties on the east side of the Olympic Mountains . The canal, which is more of a fjord, separated the Olympic from the Kitsap peninsula in Puget Sound . The Twana lived in permanent winter villages on this fjord and its rivers. In spring, summer and autumn they roamed the area with its watercourses fishing, hunting and collecting.

Their hunting grounds extended westward to the Olympic Mountains , while they were bordered to the south by the main Sahewamish village (today's town of Shelton ). The twana's neighbors to the east and southeast were the Klallam , the Squaxin, and the Suquamish ; the land of the Satsop bordered it in the southwest.

The Twana consisted of nine groups, the Dabop, Quilcine, Dosewallips, Duckabush, Vance Creek, Hoodsport, Tahuya, Duhleap and the Skokomish, which not only provided the overarching name, but also represented the largest group.

society

In the large plank houses, several related families usually lived, each of which lived in one area. The male head of one of the families was considered the head of the household and homeowner. The political structure was loose, but each village had a "high-class man" or leader who exerted great influence over community affairs. He was able to lead joint hunts and took the lead in meetings with other communities. The village chief usually had a spokesman known for his eloquence and ability to organize public ceremonies. There was also a village crier who woke the congregation in the morning with news, gossip, advice and jokes.

The men hunted deer, elk and waterfowl, but also other land animals. Their diet was based on the meat of land animals, not fish , which was not the rule among the coastal Salish . The women gathered shells, berries, mushrooms, roots and other plants. The fishing, hunting and gathering served not only to obtain food, but also provided them with skins, as well as the basic materials for blankets, baskets and wickerwork of all kinds, for clothing and with feathers. In the summer they concentrated their activities on the Channel coast, but their winter villages were on the Skokomish River and its north fork. Land could not be bought or sold. But everyone was aware that the Hood Canal was the "Twana Territory". Traps and trawls were considered the property of their manufacturer, but permission to use them was usually granted. However, houses in the village or groups of houses were clearly seen as the property of the group that built them.

trade

They traded with tribes far north and south. Strands with Dentalium shells often served as a kind of currency. There were three main types of canoes , the largest of which were known as chinook canoes. To transport large loads, large canoes were tied together like a raft. Canoes were also equipped with mat sails for salt water trips. With the lively trade in food, clothing, baskets, weapons, etc., there was also a constant exchange of traditions, languages, chants, and relationships with the Satsop , Squaxin , Suquamish , Klallam, and other tribes.

Ceremonies and powers

The most important ceremonies were celebrations on the occasion of the capture of the first animals of the season, especially the first salmon and the first moose. The "First Salmon Ceremony" was held in honor of the first salmon caught of the season. The fish was brought upstream to the village by two elders, then fried, and the whole village participated in the consumption of the fish. After the meal, the salmon's bones were put back into the river so that they could return to their people. There the first salmon was supposed to report on the friendly treatment and respect that the tribe had shown them. Similar ceremonies related to the first moose of the year and other game animals.

Another important ceremony was the potlatch , which was practiced by most of the coastal Salish tribes , but also further north. One of the best ways to increase his standing for a senior man was to hold a potlatch, where he invited other communities to dine, entertained them with games, competitions, chants, and dances, and hosted as many gifts as he could afford could. The wealthier the host was, the more generously he should give away. A potlatch could last days or weeks and was concluded with the distribution of goods, the host performed his power chant and the guests received provisions for the trip. Potlatches were usually held in the fall, after the summer fishing, hunting and gathering seasons. Often a separate potlatch house was built for this.

In all ceremonies there was a special relationship with supernatural guardian spirits. Each ward member had an opportunity in childhood and adolescence to prepare for a vision that would come as they began to mature. Elderly members of the ward taught and prepared the youth for this ritual in which they would be alone, fast, and seek a vision. In this vision a personal guardian spirit (the spiritual counterpart of a being from nature, often an animal) would reveal itself to the seeker. He would describe his powers and abilities and recite a magical chant that the person concerned could sing to call the guardian spirit at winter ceremonies or in times of need.

Through these ceremonial chants and dances, together with his own skill, talents and luck, the person concerned would clearly indicate which spiritual animal his guardian spirit was, but the twana would never reveal this information directly. They believed that such a pronounced preaching could endanger the relationship and lead to loss of strength or even death. Someone with a good and close relationship with the personal guardian spirit was strong and capable; whoever was without this relationship or who did not take care of it properly became weak and unable.

Contacts with fur traders

Even the fur trade of the late 18th century had the effect of a distant tremor, because even without direct contact, the economy changed, especially trade, but also the armament and the distribution of power in the greater area between California and Alaska . In 1792 George Vancouver came to what would later become Seattle . The first smallpox epidemics were already rampant among the tribes of the north-west coast , and the Skokomish were also affected. The worst epidemic was that of 1775 .

Mighty tribes from the north, where the fur traders had exchanged weapons for furs, came to the south in search of slaves. The Yakima tribe east of the Cascade Range also robbed the Puget Sound and sold tribesmen to the Columbia River . The Suquamish chief Kitsap even led a campaign with other tribes to Vancouver Island to prevent the Cowichan from further attacks.

The Hudson's Bay Company built Fort Langley in 1827 and Fort Nisqually in 1833 near what is now Dupont . The first American settlements emerged in 1851 and 1852.

reserve

On January 26, 1855, the United States and the Washington Territory signed the Treaty of Point-No-Point with the Skokomish, Twana, Klallam and Chimakum. As a result of this agreement, the Skokomish settled in the south-western end of the Hood Canal located Skokomish Indian Reservation to which the current core area of Mason County is located near the Skokomish River. The reserve extends on both sides of US 101 north of Shelton .

Many of the Klallam and Chimakum stayed in their villages on the Hood Canal and Puget Sound after the reservation was established. In 1870 the government forced the Klallam chief to go to the reservation, but he was buried in his traditional area, ie Chitsamakkan was buried in the Masonic cemetery in Port Townsend .

The reserve now covers 21.244 km², and in the year 2000 730 people lived there, in the wider area over 1200. The central place is Skokomish . Many Skokomish also live in the surrounding areas. In 1984 there were 504 tribal members, in 1989 there were 829.

Shaker Church, struggle for land rights, self-government

The Indian Shaker Church , established by the Squaxin in 1882 , combined Christian principles and Indian spirituality. From there some squaxin came to the Skokomish reservation.

Around 1900 a flood destroyed the Skokomish estuary. The following dikes transformed the landscape, and the basic for the Skokomish and their weaving sweetgrass ( sweet grass ) disappeared. Fishing in the tidal range was also subject to ever increasing restrictions, so that coastal fishing fell sharply. Between 1926 and 1930, the city of Tacoma built two dams at the northern fork of the Skokomish, which destroyed or buried substantial parts of the traditional sites. Potlatch State Park was set up in 1960 - without any involvement from the natives.

From 1938 the tribe was governed by the Indian Reorganization Act , governed by a Tribal Council . On June 30, 1961, the Skokomish received compensation of $ 373,577 for the 3,558 km² of land taken from them in 1855 , excluding the $ 53,383 previously paid. In 1973 the tribe paid a portion of this to each tribe member. So everyone got $ 250 for a total of $ 104,000.

Current situation

The Skokomish Tribal Council is the ruling body of the tribe. It is based on Articles III and VI of the Constitution, which were supplemented by the statutes of the Skokomish in the reservation and recognized by the Second Secretary of State for the Interior on February 23, 1938. The tribal council consists of seven members who are elected in three-year intervals.

Of the 4,986.97 acres that the reservation encompasses today, 3,000 are trust land owned by the tribe.

A fish factory was acquired in 1965, and fish farming began in 1976. In 1974 the tribe obtained the return of various fishing rights. In addition to declining logging, a gas station with an attached shop has proven to be a small source of income. Above all, the revival of traditional techniques has in retrospect also proven to have economic consequences. Wood carving and basket weaving are very popular, which in turn promotes tourism.

On October 5, 2007, the tribe leased the Waterfront Resort at Potlatch in order to enter tourism on a larger scale. This also includes Bird Watching Tours , i.e. bird watching.

In addition, the tribe maintains the Lucky Dog Casino . Such casinos are more like a mixture of concert hall and restaurant, hotel and entertainment company than a pure gambling establishment.

The institute, intricately named Skokomish Indian Tribe's Tribal Historic Preservation Office (THPO), deals with the history and preservation of historical sources. A language revitalization program has been in place since the 1970s. In addition to the Shaker Church and the Indian Pentecostal Church, there is another group that adheres to the traditional Tamanawas religion, which is particularly popular with younger people.

See also

literature

- Reverend Myron Eells: Ten Years of Missionary Work Among the Indians at Skokomish, Washington Territory 1874-1884. Congregational Sunday-School and Publishing Society, Boston: 1886

- William W. Elmendorf: Twana Narratives. Native Historical Accounts of a Coast Salish Culture , University of British Columbia Press 1993, ISBN 978-0-7748-0475-2

- Robert H. Ruby and John A. Brown: A Guide to the Indian Tribes of the Pacific Northwest , University of Oklahoma Press, 2nd Ed. 1992, pp. 209-211 and 248f. ISBN 0-8061-2479-2

Web links

- Homepage of the Skokomish

- Skokomish Casino website

- Coast Salish Villages of Puget Sound Overview of the Coastal Salish Tribes

- Overview map

- THPO website, under construction

Remarks

- ↑ Article in Skokomish Sounder v. November 2007 (PDF, 3.4 MB) ( Page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. .