Sondhi Limthongkul

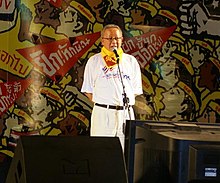

Sondhi Limthongkul ( Thai สนธิ ลิ้ม ทอง กุล , RTGS Sonthi Limthongkun , pronunciation: [sǒntʰíʔ límtʰɔːŋkun] ; born November 7, 1947 in Sukhothai Province ) is a Thai media entrepreneur and political activist. He is the founder of the media group around the daily Phuchatkan ("Manager") and the satellite and cable television broadcaster ASTV. From 2006 to 2013 he was one of the prominent leaders of the People's Alliance for Democracy (PAD) known as the "Yellow Shirts" movement.

Origin, education, media business

Sondhi belongs to the ethnic group of Thais of Chinese descent . His grandfather immigrated from Hainan at the end of the 19th century . Sondhi studied history at the University of California, Los Angeles and Utah State University .

After his return to Thailand, he first worked as a journalist for the newspaper Prachathippatai ("Democracy"), which supported the 1973 popular uprising against the military government by students . In 1983 he founded the business-related weekly Phuchatkan Rai Sapda ("Manager Weekly"). In 1990 the daily Phuchatkan Rai Wan ("Manager Daily") was added, which was primarily aimed at younger, career-conscious city dwellers. In the same year he brought the Manager Media Group to the stock exchange. With his publications, Sondhi represented the predominantly Chinese-born business elite and sought to limit the influence of the bureaucracy. He supported the prime minister Chatichai Choonhavan , who was ousted by a military coup in 1991. The Phuchatkan group media wrote against General Suchinda Kraprayoon's junta , calling itself the National Peace Keeping Council (NPKC), questioning its credibility. Sondhi's newspaper campaigned for civil rights and threatened to be banned during the " black corn " of 1992 because it printed pictures of the mass protests against the military-backed government and the military action against the demonstrators.

In the 1990s, Sondhi expanded beyond Thailand's borders: in 1992 he launched the glossy business magazine Asia, Inc. , followed in 1995 by the daily newspaper Asia Times , which was conceived as a genuine Asian, English-language leading medium for the region . In commentaries and editorials he took a stand for the emancipation of Asian states from Western influence, for “Asian values” and for the priority of economic development over Western ideas of human rights. In 1996, Sondhi's net worth was estimated at $ 600 million. He referred to himself as the "Asian Rupert Murdoch ". Sondhi founded the non-profit Chaiyong Limthongkul Foundation, which promoted culture and science and whose chairman was the political scientist and constitutional judge Chai-anan Samudavanija . For his investments, however, he had taken out enormous loans. When the financial crisis hit Thailand and other Asian countries in 1997 , he went bankrupt.

Sondhi was a business partner of the telecommunications company Thaksin Shinawatra . This supported him in rebuilding his media business. In return, Sondhi welcomed Thaksin's entry into politics and, after his election victory in 2001, praised him as "the best prime minister Thailand has ever had". When the Thai Constitutional Court ruled on corruption allegations against Thaksin and a possible political ban for him, Sondhi stood by his side. Phuchatkan threatened that sentencing Thaksin would be the end for Thailand.

Political activity as a “yellow shirt” leader

Protests against Thaksin in 2005/06

From 2004, however, Sondhi appeared as a critic of Thaksin. The reason for the sudden break between the two is believed to be the premier's refusal to allow Sondhi to have his own television station. Sondhi used his group's media to spread allegations of corruption and abuse of power against the head of government. In September 2005, Sondhi's weekly television program Mueang Thai Rai Sapda ("Thailand Weekly"), in which he commented on the political events , was canceled by Kanal 9 , which is operated by the state-owned broadcaster MCOT. This was justified on charges of lese majesty and unilateral attacks by Sondhi, which led to legal proceedings. Sondhi declared the end of the program, however, as politically motivated. Prior to this, Prime Minister Thaksin had sued Sondhi for defamation on payment of 500 million baht for allegedly disloyalty to the king.

According to the Southeast Asian scholar Michael J. Montesano, the removal of Mueang Thai Rai Sapda was a turning point from which the anti-Thaksin forces grew into a mass movement. Sondhi continued the broadcast on satellite television and the Internet and recorded it now instead of in the studio at public gatherings in Bangkok's Lumphini Park . The movement was further boosted when it was announced in January 2006 that Thaksin and his family had sold 73 billion baht ($ 2 billion) of stake in their Shin Corporation to the Singaporean state-owned investment company Temasek Holdings without paying tax to have to.

In February 2006, Sondhi joined forces with other anti-government activists and groups to form the People's Alliance for Democracy (PAD). Its first meeting on February 4 was attended by an estimated 50,000 people, calling for the Prime Minister to resign. Yellow shirts became their distinguishing mark - the color yellow is associated with the birthday of King Bhumibol Adulyadej in the Thai color symbolism . Sondhi claimed for himself and his movement to fight for the king and thus captured the monarchy for his political commitment. Through his private secretary and the President of the Privy Council, Prem Tinsulanonda , Sondhi and the PAD submitted a petition to the King to dismiss Thaksin and appoint a new head of government.

While the heterogeneous PAD - which also included trade unionists, farmers, democracy and social activists - initially focused on issues such as the rejection of privatization, human rights violations and corruption, Sondhi directed the movement's rhetoric more and more towards nationalism and royalism. Sondhi accused Thaksin not only of a lack of respect for the monarchy and striving for autocracy, but also of the destruction of religion: When a mentally deranged destroyed the highly venerated statue of the god Brahma in the Erawan shrine in March 2006 , Sondhi blamed the prime minister for it. In May 2006, Sondhi's Manager-Magazin published a series of reports on the supposed Finland plot according to which Thaksin planned to abolish the monarchy and turn Thailand into a one-party state based on the communist model. Two days after the military coup on September 19, 2006 , the PAD disbanded for the time being.

Protests against the government in 2008

After the coup, Sondhi hosted another television program, this time under the title Yam Fao Phaendin ("Protector of the Nation"). It was broadcast on government owned Channel 11 . After the return to democracy and the election victory of the Thaksin-affiliated Party of People's Power in December 2007 and the assumption of government by Samak Sundaravej in January 2008, Sondhi revived the “yellow shirts” movement. He accused the prime minister and his government of being mere puppets of Thaksin, who had fled abroad. In March 2008, Sondhi was sentenced to two years' imprisonment for insulting a government official and was suspended .

From around July 2008 the “yellow shirts” no longer called for democracy, but for a “new policy”. At that time, Sondhi declared that democracy was only a “Western export article” and that at least a democracy based purely on elections was not the right form of government for Thailand because most voters lack the “intelligence and wisdom” to use their political rights sensibly. Instead, the PAD proposed a parliament with only 30% of its members elected, while 70% should be appointed by professional and similar associations. Sondhi and his PAD also called for a tough line in the border dispute between Thailand and Cambodia over the historic Prasat Preah Vihear temple . Among other things, Sondhi called on the Thai army to capture Cambodia's national landmark Angkor Wat and then negotiate a return in exchange for Preah Vihear and the disputed 4.6 km² area.

The "yellow shirts" appeared increasingly militant, from August 2008 they besieged the government building. In October there were violent clashes between police and PAD activists, some of whom were armed. On October 29, 2008, Sondhi accused Thaksin of using dark magic to rob symbols of national worship of their holy power: he had removed a stone from behind the Emerald Buddha and stakes in a hexagram around the equestrian statue of King Rama V in the ground rammed so that these sanctuaries could no longer radiate their power. Sondhi's followers performed rituals to reverse these damaging spells . Another conviction followed in December 2008 in a 2005 trial for defamation of Thaksin, this time to three years in prison. The sentence was changed to a six-month suspended sentence in 2010.

Actions since 2008

On April 17, 2009, an assassination attempt was carried out on Sondhi. Unidentified shooters shot his car with assault rifles of the types AK-47 and M16 as it drove past . He, his driver and his assistant were injured. Sondhi suffered a severe head wound and had to remove shrapnel from his temple. After the PAD had alienated itself from the Democratic Party , which was once allied with it, it founded its own party in October 2009: the Party for New Politics ( Phak Kanmueang Mai or New Politics Party , NPP). Sondhi became its first chairman after clearly winning an internal PAD membership survey. In May 2010, however, he resigned and handed over the chairmanship to Somsak Kosaisuuk. Before the parliamentary elections in July 2011 , an internal conflict developed in the camp of the “yellow shirts”. While Somsak Kosaisuuk wanted to take part in the election with the party for new politics, Sondhi planned an election boycott and demanded a temporary end to all party politics. As a result, Sondhi left the NPP and Somsak left the PAD.

In February 2012, Sondhi was sentenced to 20 years in prison for fraud. The court found that between 1996 and 1998 he forged documents to obtain a loan from Krung Thai Bank for 1.07 billion baht (US $ 36 million). However, he was released on bail for the time being. In August 2013, the remaining leaders of the PAD, including Sondhis, resigned as one. The organization has been effectively dissolved since then. From it, however, emerged the " People's Democratic Force to Overthrow Thaksinism " ( Pefot), which during the mass protests against the government in November 2013 in the "People's Committee for Complete Democracy with the King as Head of State" emerged. In it, however, Sondhi no longer played a leading role.

In October 2013, Sondhi was found guilty of lese majesty . He had on a PAD meeting in 2008 expressions of opposition " red shirts " -Aktivistin Daranee Charnchoengsilpakul ( "Da Torpedo") repeated for this was later sentenced to 15 years in prison. The court ruled that the mere repetition of the statements constituted a libel of majesty. However, he was only sentenced to two years in prison. During the appeal proceedings before the Supreme Court, he initially remained free on bail. In August 2014, an appeals court upheld the first-instance ruling in the 2012 fraud case and refused to be released on bail for the duration of the appeal by the Supreme Court, so that he had to go to prison for the first time. After 18 days in prison, the Supreme Court again granted him a bail payment on deposit of 12 million baht.

Web links

- Stolen daughter (portrait via Sondhi Limthongkul). In: Der Spiegel , No. 15/1996, pp. 146–148.

literature

- John Funston (Ed.): Divided Over Thaksin. Thailand's Coup and Problematic Transition. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, Singapore 2009.

- Nicholas Grossman (Ed.): Chronicle of Thailand. Headline News Since 1946. Editions Didier Millet, Singapore 2009.

- Puangthong R. Pawakapan: State and Uncivil Society in Thailand at the Temple of Preah Vihear. ISEAS Publishing, Singapore 2013.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Jean Baffie: Les Hainanais de Thaïlande. Une minorité tournée vers Bangkok plus que vers Haikou. In: Hainan. From China to Southeast Asia. Harrassowitz Verlag, Wiesbaden 2000, p. 270.

- ↑ Deirdree Carmody: The media business; Thai Publisher Plans to Expand Empire in US In: The New York Times , October 12, 1992.

- ^ A b Daniel Ten Kate, Anuchit Nguyen: Thai Protest Leader Sondhi Given 20-Year Jail Term for Fraud. In: BloombergBusinessweek , February 28, 2012.

- ^ Manager launches new weekly business paper. In: Chronicle of Thailand. 2009, p. 252.

- ^ Status of Media in Thailand. In: Donald H. Johnston (Ed.): Encyclopedia of international media and communications. Volume 4, Academic Press, 2003, p. 477.

- ^ A b Justin Doebele: Too much, too soon. In: Forbes , October 20, 1997.

- ^ A b c Duncan McCargo : Thai Politics as Reality TV. In: The Journal of Asian Studies , Volume 68, No. 1, February 2009 doi : 10.1017 / S0021911809000072 , p. 8.

- ^ McCargo: Politics and the Press in Thailand. Media machinations. Routledge, London, 2000.

- ^ A b Glen Lewis: Virtual Thailand: The Media and Cultural Politics in Thailand, Malaysia and Singapore. Routledge, Abingdon / New York 2006, p. 28.

- ^ Stir-fried news. In: The Economist , December 9, 1995.

- ↑ Stolen daughter. In: Der Spiegel , No. 15/1996, pp. 146–148.

- ↑ a b Patit Paban Mishra: The History of Thailand. P. 166.

- ↑ Richard Covington: Asian 'Murdoch' In Hard Times. Sondhi's Media Empire Ailing. In: International Herald Tribune , May 8, 1997.

- ↑ a b Gerald W. Fry, Gayla S. Nieminen, Harold E. Smith: Historical Dictionary of Thailand. 3rd edition, Scarecrow Press, Lanham MD / Plymouth 2013, p. 307.

- ↑ Thitinan Pongsudhirak: The Tragedy of the 1997 Constitution. In: Divided Over Thaksin. 2009, p. 33.

- ↑ Federico Ferrara: Thailand Unhinged. Unraveling the Myth of a Thai-style Democracy. Equinox Publishing, Singapore 2010, p. 45.

- ↑ Michael J. Montesano: Political Contests in the Advent of Bangkok's September 19 coup. In: Divided Over Thaksin. 2009, p. 2.

- ^ Sondhi's talk show axed by Channel 9. In: Chronicle of Thailand. 2009, p. 388.

- ^ John Funston: Introduction. In: Divided Over Thaksin. 2009, p. Xiv.

- ↑ Michael Kelly Connors: Democracy and National Identity in Thailand. 2nd edition, NIAS Press, Copenhagen 2007, p. 269.

- ^ Montesano: Political Contests in the Advent of Bangkok's September 19 coup. 2009, pp. 3-4.

- ^ A b Montesano: Political Contests in the Advent of Bangkok's September 19 coup. 2009, p. 4.

- ^ People's Alliance for Democracy Born. In: Chronicle of Thailand. 2009, p. 391.

- ^ Connors: Democracy and National Identity in Thailand. 2nd edition, NIAS Press, Copenhagen 2007, p. 270.

- ↑ James Ockey: Thailand in 2008. Democracy and Street Politics. In: Southeast Asian Affairs 2009. ISEAS Publications, Singapore 2009, p. 317.

- ↑ Puangthong R. Pawakapan: State and Uncivil Society in Thailand at the Temple of Preah Vihear. 2013, pp. 57–59.

- ^ A b Justin Thomas McDaniel: The Lovelorn Ghost and the Magical Monk. Practicing Buddhism in Modern Thailand. Columbia University Press, New York 2011. ISBN 978-0-231-15376-8 , pp. 155.

- ^ Fry, Nieminen, Smith: Historical Dictionary of Thailand. 2013, pp. 162-163.

- ^ Surayud cabinet under pressure. In: Chronicle of Thailand. 2009, p. 399.

- ^ A b Freedom House: Freedom of the Press 2008. A Global Survey of Media Independence. Rowman & Littlefield, Lanham MD / Plymouth 2009, p. 322.

- ↑ a b Kesinee Taengkhiao: Sondhi loses appeal, gets 20 years in prison. In: The Nation , August 8, 2014.

- ↑ Federico Ferrara: Thailand Unhinged. Unraveling the Myth of a Thai-style Democracy. Equinox Publishing, Singapore 2010, p. 51.

- ↑ Political Crisis: Thailand's Democracy Endangered. N-tv.de, November 26, 2008.

- ↑ Puangthong R. Pawakapan: State and Uncivil Society in Thailand at the Temple of Preah Vihear. 2013, p. 77.

- ^ " Chang Noi ": PAD saves the nation from supernatural attack. In: The Nation , November 10, 2008.

- ↑ Thai 'Yellow Shirt' founder Sondhi Limthongkul jailed. Australia Network News, August 8, 2014.

- ^ PAD leader Sondhi survives assassination attempt. In: Chronicle of Thailand. 2009, p. 412.

- ↑ Michael H. Nelson : People's Alliance for Democracy. From 'New Politics' to a 'Real' Political Party? In: Legitimacy Crisis and Political Conflict in Thailand. Silkworm Books, Chiang Mai 2010, pp. 150–151.

- ^ Fry, Nieminen, Smith: Historical Dictionary of Thailand. 2013, p. 274.

- ^ Chairat Charoensin-o-larn: Thailand in 2012. A Year of Truth, Reconciliation, and Continued Divide. In: Southeast Asian Affairs 2013. ISEAS Publishing, Singapore 2013, p. 293.

- ^ Anti-Thaksin forces seen as regrouping. In: Bangkok Post , August 25, 2013.

- ↑ Aim Sinpeng: Who's who in Thailand's anti-government forces? In: New Mandala , November 30, 2013.

- ^ Founder of Thailand's Yellow Shirts convicted of insulting the king. In: Zeit Online , October 1, 2013.

- ↑ Kate Hodal: Thai monarchy laws need reviewing, say critics pointing to recent cases. In: The Guardian , October 3, 2013.

- ↑ Sondhi bailed after 18 days in jail. In: Bangkok Post , August 25, 2014.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Sondhi Limthongkul |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Phuchatkan; สนธิ ลิ้ม ทอง กุล (ThS) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Thai media entrepreneur and political activist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | November 7, 1947 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Sukhothai |