Stokesay Castle

Stokesay Castle is a fortified manor house in the village of Stokesay in the English county of Shropshire . Laurence of Ludlow , the leading wool merchant in England at the time, had it built at the end of the 13th century, because he wanted to create a secure home for himself and his family and also income from a commercially operated property. Laurence's descendants remained in possession of the castle until the 16th century, when it was sold to various private owners. At the outbreak of the English Civil War in 1641, Stokesay Castle belonged to William Craven , the first Earl of Craven and supporter of King Charles I. After the collapse of the royalist advances in 1645, the Roundheads besieged the castle in June and quickly forced the garrison to give up. Parliament ordered the razing of the castle, but there were only minor damage done to the castle wall, so that the family Baldwyn the castle could be used as a residence until the end of the 17th century.

In the 18th century, the Baldwyns leased the castle for agricultural and manufacturing purposes. It slowly fell into disrepair, and on his visit in 1813, the archaeologist John Britton noted that it was "abandoned, neglected and quickly deteriorated ." In the 1830s and 1850s, William Craven, 2nd Earl of Craven , had restoration work carried out. In 1869 the Cravens' estate, who were now in heavy debt, was handed over to the wealthy industrialist John Derby Allcroft , who paid for additional expensive restoration work in the 1870s. Both owners tried to limit changes to the existing buildings during the restoration work, which was unusual for the time. The castle became popular with tourists and artists and was officially opened to paying visitors in 1908.

Allcroft's descendants ran into financial difficulties in the early 1900s and found it increasingly difficult to keep up with Stokesay Castle. In 1986, Jewell Magnus-Allcroft finally agreed to put Stokesay Castle under the management of English Heritage , and after his death in 1992, ownership of it passed to the organization. English Heritage carried out an extensive restoration of the castle in the late 1980s. Today, in the 21st century, Stokesay Castle continues to serve as a tourist attraction, visited by 39,218 guests in 2010.

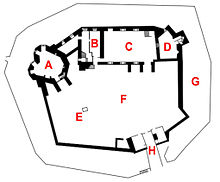

From an architectural point of view, Stokesay Castle is "one of the best preserved fortified mansions in England", according to the archaeologist Summerson . The castle consists of a castle wall with moat with an entrance through a half-timbered - gatehouse of the 17th century. In the courtyard there is a stone knight's hall and a solar block, which is protected by two stone towers. The knight's hall is equipped with a wooden beam ceiling from the 13th century and carved stone figures from the 17th century adorn the gatehouse and the solar. It was never intended to serve as a serious military fortification, but its style was based on the much larger castles Edward I had built in North Wales . Originally intended as a prestigious, safe and comfortable home, the castle has undergone little change since the 13th century. It is a rare example of an almost complete ensemble of medieval buildings that has been preserved to this day. English Heritage has kept the amount of display material on the property to a minimum and has left the castle largely unfurnished.

history

13th to 15th centuries

Stokesay Castle was built in the village of Stokesay in the 1280s and 1290s at the behest of Laurence of Ludlow , a very wealthy wool merchant. The name Stokesay is derived from the Anglo-Saxon word stoches (German: Rinderhof) and the name of the Say family , who owned the land from the 12th century. In 1241 Hugh de Say sold Stokesay to John de Verdon . He went on the Seventh Crusade in 1270 and mortgaged the land for life to Philip de Whichcote . John de Verdon died in 1274 and bequeathed the rights to his estates to his son, Theobald de Verdon .

Laurence of Ludlow bought Stokesay in 1281 from Theobald de Verdon and Philip de Whichcote, presumably for about £ 266, which he could easily afford because he had made a fortune in his wool trade. Laurence exported wool from the Welsh Marches , traveled all over Europe and had offices in Shrewsbury and London . He had become the richest wool merchant in England, helped the government to determine its trade policy and lent money to the high nobility. Stockesay Castle was supposed to be a safe place to live for Laurence, conveniently located near his other shops in the area. It was also intended to serve as a commercial property as it yielded around £ 26 a year from 49 acres of agricultural land, 2.4 acres of meadows, extensive open forest, watermill and pigeon houses .

Construction on the castle began sometime in 1285 and Laurence moved into his new home in the early 1290s. The castle was, as Nigel Pounds describes it, "both presumptuous and comfortable". At first it consisted of living quarters and a tower in the north. In 1291 Laurence got permission from the king to fortify his house (English: license to crenellate), and he took advantage of this permission and soon had a south tower added, which looked particularly martial.

In November 1294 Laurence was drowned in the sea off the south coast of England and his son, William of Ludlow , is believed to have had some final work done on Stokesay Castle. His descendants, also named Ludlow , owned Stokesay Castle until the end of the 15th century. Then the castle fell to the Vernon family by marriage .

16th and 17th centuries

Stokesay Castle was passed on to Thomas Vernon's grandson Henry Vernon in 1563 . The family hoped to be raised to the nobility and - possibly as a result - the property was officially referred to as the "castle" for the first time at this time. Henry Vernon spent part of his time in Stokesay and the rest in London. Presumably he lived in the north tower. He vouched for the debts of a business partner and, when the latter could not pay them, he had to stand up for it and sit in fleet prison for a while . In 1598 he sold the castle for £ 6,000 to pay off his own heavy debts. The new owner, George Mainwaring , sold the property on in 1620 for £ 13,500 through a consortium of investors to a wealthy widow and former mayor's wife of London, Dame Elizabeth Craven . The lands around Stokesay Castle were now valuable: they made about £ 300 a year.

Elizabeth's son, William Craven , spent little time at Stokesay Castle and from the 1640s leased it to Charles Baldwyn and his son Samuel . He had the gatehouse rebuilt in 1640 and 1641 at a cost of around £ 533. In 1643 the English civil war broke out between the supporters of King Charles I and those of Parliament. William Craven, a supporter of the royalists , spent the war years at the court of Elizabeth Stuart in The Hague and donated large sums of money to the king's war efforts. William Craven garrisoned the castle; the Baldwins were also staunch royalists, and as the conflict progressed the entire county of Shropshire increasingly sided with the king. Nonetheless, by the end of 1644, groups of vigilant clubmen emerged in Shropshire complaining about the activities of the royalist forces in the region and a. demanded the dissolution of the garrison of Stokesay Castle.

In early 1645 the fortunes of war had turned decisively against the king and in February parliamentary forces took the city of Shrewsbury . This exposed the rest of the region to attack, and in June a parliamentary force of 800 marched south towards Ludlow, attacking Stokesay Castle along the way. The royalist garrison under Captain Daurett was vastly outnumbered and would have been unable to effectively defend the new gatehouse, which was essentially for decoration. Nonetheless, both sides complied with the protocol of the art of war at that time, which ended in a bloodless victory for the parliamentary troops: the besiegers demanded that the garrison surrender, the garrison refused, the attackers demanded a second time to give up and this time the garrison could surrender with honor.

Soon after, on June 9, 1645, a royalist force led by Sir Michael Woodhouse tried to retake the castle, which was now occupied by a parliamentary garrison. The counterattack was unsuccessful and ended with the wild flight of the royalist troops and a skirmish in the nearby village of Wistanstow .

Unlike many other castles in England, which were deliberately badly damaged or even razed to make them unusable for military use, Stokesay Castle escaped such a fate after the war. Parliament took over the lands from William Craven and ordered the castle to be razed in 1647, but then only had the curtain torn down and the rest of the complex untouched. Samuel Baldwyn returned in 1649 and leased the castle from Parliament during the Commonwealth of Nations. He equipped parts of the castle with wooden paneling and new windows. With the return of Charles II to the throne in 1660, William Craven got his lands back and the Baldwyns leased the castle from him again.

18th and 19th centuries

The Baldwyn family continued to lease the castle through the 18th century, but they continued to lease it to various tenants. The castle no longer served as a residential building. Two half-timbered buildings, which were attached to the knight's hall, were demolished around 1800 and at the beginning of the 19th century the castle was used as a granary and for handicraft businesses such as cooper , mint and blacksmith .

The castle began to deteriorate and the archaeologist John Britton noted during his visit in 1813 that it was “abandoned, neglected and quickly turned into ruin: the window glass has been destroyed, ceilings and floors have collapsed and the rain pours through the open roof onto the damp and damp modernizing the walls. ”The operation of the forge on the ground floor of the south tower led to a fire in 1830 that severely damaged the castle and affected the entire south tower. Extensive deterioration of the pressure pads in the roof of the castle endangered the knight's hall in particular, as the rotting roof pushed the walls apart.

William Craven , the Earl of Craven , had restoration work carried out in the 1830s. This was an attempt to secure the existing buildings and not rebuild them. This was an unusual request at the time. By 1845 stone buttresses and pillars had been built in to support the knight's hall and roof. A study by Thomas Turner revealing the history of the castle was published in 1851. Frances Stackhouse-Acton , a local landowner, showed particular interest in the castle and in 1853 convinced William Craven to have further repairs carried out on it under her supervision for £ 103.

In 1869, John Derby Allcroft bought the Cravens' 2,100 acre property mortgaged to secure the owner's debts for £ 215,000. Allcroft was the head of Dents, a well-known glove manufacturer, which made him extremely rich. The lands also included Stokesay Castle, where Allcroft had extensive restoration work carried out over several years from 1875. Stokesay Castle really needed the repairs: The writer Henry James , who visited the castle, noted in 1877 that the property was "in a state of extreme decline".

Allcroft did what archaeologist Gill Chitty described as a "simple and unaffected" work program that generally tried to avoid excessive tampering. He may have been influenced by the contemporary writings of the local vicar , Reverend James La Touche , who took a somewhat romanticized approach to analyzing the castle's history and architecture. The castle had become a popular destination for tourists and artists in the 1870s, and the gatehouse was converted into a house for a caretaker to look after the property. After the restoration work was carried out, the castle was back in good condition at the end of the 1880s.

20th and 21st centuries

Further repairs to Stokesay Castle were necessary in 1902. Allcroft's heir, Herbert , had it carried out with the help of the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings . The Allcroft family got into increasing financial difficulties in the 20th century and so the castle was officially opened to the public in 1908. Most of the income generated in this way was reinvested in the property, but there was hardly enough money for repairs. In the 1930s, the Allcrofts' estates were in dire financial straits, and inheritance taxes imposed in 1946 and 1950 only added to those difficulties.

Despite the high number of visitors - over 16,000 came in 1955 - maintaining the castle became increasingly difficult and so the state was asked to take over the property. For many decades the owners, Philip and Jewell Magnus-Allcroft , rejected these proposals and continued to operate the castle privately. In 1986, Jewell Magnus-Allcroft finally agreed to put Stokesay Castle under the administration of English Heritage , and after her death in 1992, the castle was wholly owned by that organization.

The castle was transferred to English Heritage largely unfurnished and with a minimal amount of explanatory material. It also had to be renovated again. There were various options for having the necessary work carried out, e.g. This includes, for example, the restoration of the castle in the style of a specific epoch from its history, the use of interactive approaches such as “ Living History ” for communication with visitors or the use of the site to show the restoration methods of different epochs. All of these proposals were discarded and instead a policy of minimizing physical interference during the restoration and maintaining the buildings in the condition in which they were given to English Heritage, including the lack of furniture, was adopted. Archaeologist Gill Chitty described this as encouraging visitors to "personally discover their feel for historical connections and events". With this in mind, an extensive program of restoration work was carried out from August 1986 to December 1989.

Today, in the 21st century, Stokesay Castle continues to be operated as a tourist attraction by English Heritage; In 2010 39,218 visitors came. In 2010, British Airways and English Heritage named one of their Boeing 757s “Stokesay Castle”. The castle is a Grade I Historic Building and Scheduled Monument under UK law .

architecture

construction

Stokesay Castle was built on a gently sloping site in the Onny Valley . A block of solar and knight's hall was created, to which a north and a south tower were added. This type of construction was not uncommon in 13th century England, especially in the north of the country. A fortified curtain wall , which was destroyed in the 17th century, enclosed the courtyard. A gatehouse - probably originally built of stone and then rebuilt as a half-timbered building around 1640 - guards the entrance. The castle wall may have reached a height of 10 meters (measured from the bottom of the moat). The castle courtyard, about 46 meters by 38 meters, contained additional buildings throughout the history of the castle, presumably also a kitchen, a baking house and storage rooms, all of which were demolished around 1800.

The castle was surrounded by a moat that was between 4.6 and 7.6 meters wide, but I do not know whether the moat was originally dry as it is today or was filled with water from a pond or a nearby watercourse. The excavation from the moat was used to fill the castle courtyard. Outside the moat there was a lake and various ponds that should be seen from the south tower. The parish church of St. John the Baptist of Norman origin, but largely rebuilt in the middle of the 17th century, is right next to the castle.

Stokesay Castle forms what archaeologist Gill Chitty describes as "a comparably complete ensemble" of medieval buildings, and their almost unchanged preservation to this day is extremely rare. Historian Henry Summerson considers the castle "one of the best preserved fortified mansions in England".

building

The gatehouse is a two-story, timber-framed building from the 17th century, built in a special Shropshire style. It shows fine carvings on the outer and inner passage, e.g. B. Angels , the biblical figures Adam and Eve and the serpent from the Garden of Eden , as well as dragons and other naked figures. It was intended as an ornamental building of little defense value.

The south tower has a plan in the form of an unequal pentagon and three floors with thick walls. The walls house the stairs and lavatory , the unevenly placed open spaces weakened its structure and meant that two large buttresses had to be attached to the tower during construction to support the walls. The current ceilings are from Victorian times , as they were installed after the fire in 1830, but the tower remained without glass windows, as in the 13th century. Instead, it has shutters for weather protection in winter. The ground floor was originally only accessible from the first floor, served as a safe storage area and contained a well. On the first floor there is an open fireplace from the 17th century, which is connected to the original fireplace from the 13th century. In the past, the second floor was divided into several rooms, but these were combined into a single chamber during the restoration, as it was originally built.

The roof of the south tower offers views of the surrounding landscape. In the 13th century, wooden plutei were probably inserted into the spaces between the battlements along the battlements, and during the English Civil War it was equipped with additional wooden reinforcements to protect the garrison.

The knight's hall and the solar block are connected to the south tower and were planned symmetrically as seen from the courtyard. The addition of additional stone struts in the 19th century changed their appearance. The knight's hall is 16.6 meters long and 9.4 meters wide. The roof is supported by three large wooden arches from the 13th century. Unlike usual for their size, they have wooden supports on the sides but no vertical central supports. The layers of cruck beams now rest on stone consoles from the 19th century, but originally reached down to the ground. Historian Henry Summerson regards the roof as "a rare holdover from that period". In the Middle Ages, a wooden screen is believed to have separated the north end of the great hall to create an enclosed dining area.

The solar block has two floors and a basement. It was believed to have served as an apartment for Laurence of Ludlow when he first moved into the castle. The solar itself is located on the first floor and is accessible via an external staircase. The wood paneling and the carved open fireplace date from the 17th century, probably from around 1640. This carving was once beautifully painted and contained spies through which the knight's hall could be observed from the solar.

The three-storey north tower can be reached via a staircase from the 13th century in the knight's hall, which leads to the first floor. The first floor was divided into two rooms soon after the tower was built. There you will find various decorative tiles, probably from Laurence's house in Ludlow. The walls on the second floor are mostly half-height made of wood, with the wooden walls protruding over the stone walls. The tower has its own open fireplace from the 13th century, even if the wooden roof is from the 19th century and was modeled on the original wooden roof from the 13th century. The windows date from the 17th century. The details and the carpenters 'personal markings on the woodwork indicate that the Knights' Hall, Solar and North Tower were all under the direction of the same carpenters in the late 1280s and early 1290s.

interpretation

... gatehouses in North Wales, in Caernarfon ...

... and should be vying for Denbigh .

Stokesay Castle should never be a serious military stronghold. As early as 1787, the archaeologist Francis Grose called it "a fortified mansion rather than a strong castle" and later his colleague Nigel Pounds described Stokesay Castle as a "lightly fortified dwelling house" that could provide some security but was not intended to withstand a military attack to resist. The archaeologist Henry Summerson describes its military details as "superficial" and Oliver Creighton characterizes Stokesay Castle as a "picturesque dwelling house" rather than a fortress.

Stokesay Castle's weaknesses included the incorrect positioning of its gatehouse, facing away from the street, and the large floor-to-ceiling windows in the great hall, making it relatively easy for intruders to get into the castle. Indeed, the castle's vulnerability may have been intentional: its builder, Laurence of Ludlow, was then a nouveau riche and likely did not want to build a fortress that would threaten the area's established Marcher Lords .

Still, Stokesay Castle was to have a dramatic, military appearance modeled on that of King Edward I's castles in North Wales. Visitors approached the castle across a causeway with a commanding view of the south tower, possibly framed by a moat and reflected in it. The south tower was likely to resemble the gatehouses of contemporary castles, such as B. that of Caernarfon or Denbigh , and probably originally shared his “banded” masonry with them. Cordingley claims that the south tower "gave the castle more prestige than security". The visitors then passed the impressive outside of the knight's hall block before entering the castle itself, which, according to Robert Liddiard, “must have been a bit of a disappointment from the perspective of the medieval visitor”.

17th century carvings

Individual evidence

- ^ A b c Henry Summerson: Stokesay Castle . Revised edition. English Heritage, London 2012. ISBN 978-1-84802-016-0 . P. 1.

- ^ Henry Summerson: Stokesay Castle . Revised edition. English Heritage, London 2012. ISBN 978-1-84802-016-0 . Pp. 25-27.

- ^ A b Henry Summerson: Stokesay Castle . Revised edition. English Heritage, London 2012. ISBN 978-1-84802-016-0 . P. 25.

- ↑ a b c James D. La Touche: Stokesay Castle in Archaeologia Cambrensis . Issue 16 (1899). P. 301.

- ^ Henry Summerson: Stokesay Castle . Revised edition. English Heritage, London 2012. ISBN 978-1-84802-016-0 . Pp. 25-26.

- ↑ It is impossible to accurately compare 13th century prices and incomes with today's prices and incomes. As a comparison, the average annual income of a baron at the time was £ 668.

- ^ Norman John Greville Pounds: The Medieval Castle in England and Wales: A Social and Political History . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1994. ISBN 978-0-521-45828-3 . P. 147.

- ^ Henry Summerson: Stokesay Castle . Revised edition. English Heritage, London 2012. ISBN 978-1-84802-016-0 . Pp. 26-27.

- ^ A b c Henry Summerson: Stokesay Castle . Revised edition. English Heritage, London 2012. ISBN 978-1-84802-016-0 . Pp. 26, 28.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l Stokesay Castle: History . Historic England. Retrieved July 9, 2015.

- ^ A b Henry Summerson: Stokesay Castle . Revised edition. English Heritage, London 2012. ISBN 978-1-84802-016-0 . P. 26.

- ^ A b Norman John Greville Pounds: The Medieval Castle in England and Wales: A Social and Political History . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1994. ISBN 978-0-521-45828-3 . P. 105.

- ^ Norman John Greville Pounds: The Medieval Castle in England and Wales: A Social and Political History . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1994. ISBN 978-0-521-45828-3 . P. 279.

- ↑ a b RA Cordingley: Stokesay Castle, Shropshire: The Chronology of its buildings in The Art Bulletin . Issue 45-2 (1963). P. 93.

- ^ Henry Summerson: Stokesay Castle . Revised edition. English Heritage, London 2012. ISBN 978-1-84802-016-0 . P. 28.

- ^ Henry Summerson: Stokesay Castle . Revised edition. English Heritage, London 2012. ISBN 978-1-84802-016-0 . P. 29.

- ^ A b c Henry Summerson: Stokesay Castle . Revised edition. English Heritage, London 2012. ISBN 978-1-84802-016-0 . P. 30.

- ^ A b Henry Summerson: Stokesay Castle . Revised edition. English Heritage, London 2012. ISBN 978-1-84802-016-0 . P. 21.

- ^ A b Henry Summerson: Stokesay Castle . Revised edition. English Heritage, London 2012. ISBN 978-1-84802-016-0 . P. 31.

- ↑ It is difficult to accurately compare 17th century prices and incomes with modern prices and incomes. £ 13,500 from then can now equate to between £ 2.4m and £ 466.5m in 2012, depending on the benchmark.

- ↑ a b c Measuring Worth Five Ways to Compute the Relative Value of a UK Pound Amount, 1830 to Present . Measuring Worth. Retrieved July 9, 2015.

- ^ A b c Henry Summerson: Stokesay Castle . Revised edition. English Heritage, London 2012. ISBN 978-1-84802-016-0 . P. 32.

- ↑ James D. Mackenzie: The Castles of England: Their Story and Structure . Volume 2. Macmillan. New York 1896. p. 157.

- ^ A b Thomas Wright: Historical Sketch of Stokesay Castle . G. Woolley, Ludlow 1921. p. 6.

- ^ A b Henry Summerson: Stokesay Castle . Revised edition. English Heritage, London 2012. ISBN 978-1-84802-016-0 . Pp. 32-33.

- ↑ Barbara Donagan: Was in England 1642-1649 . Oxford University Press, Oxford 2010. ISBN 978-0-19-956570-2 . P. 48.

- ↑ Stephen C. Manganiello: The Concise Encyclopedia of the Revolutions and Wars of England, Scotland and Ireland, 1639-1660 . Scarecrow Press, Oxford 2004. ISBN 978-0-8108-5100-9 . P. 135.

- ^ Diane Purkiss, The English Civil War: A People's History . Harper Perenniel, London 2006. ISBN 978-0-00-715062-5 . P. 153.

- ^ Ronald Hutton: The Royalist War Effort 1642-1646 . 2nd Edition. Routledge, London 1999. ISBN 978-0-203-00612-2 . P. 165.

- ^ CV Wedgwood: The King's War, 1641-1647 . Fantana History, London 1970. p. 397.

- ^ CV Wedgwood: The King's War, 1641-1647 . Fantana History, London 1970. p. 399.

- ^ Adrian Pettifer: English Castles: A Guide by Counties . Boydell Press, Woodbridge 2002. ISBN 978-0-85115-782-5 . Pp. 217-218.

- ^ Thomas Wright: Historical Sketch of Stokesay Castle . G. Woolley, Ludlow 1921. p. 13.

- ^ Henry Summerson: Stokesay Castle . Revised edition. English Heritage, London 2012. ISBN 978-1-84802-016-0 . P. 33.

- ^ Henry Summerson: Stokesay Castle . Revised edition. English Heritage, London 2012. ISBN 978-1-84802-016-0 . Pp. 33-34.

- ^ Thomas Wright: Historical Sketch of Stokesay Castle . G. Woolley, Ludlow 1921. pp. 13-14.

- ^ A b c Henry Summerson: Stokesay Castle . Revised edition. English Heritage, London 2012. ISBN 978-1-84802-016-0 . P. 34.

- ^ Adrian Pettifer: English Castles: A Guide by Counties . Boydell Press, Woodbridge 2002. ISBN 978-0-85115-782-5 . P. 218.

- ^ Thomas Wright: Historical Sketch of Stokesay Castle . G. Woolley, Ludlow 1921. p. 15.

- ↑ RA Cordingley: Stokesay Castle, Shropshire: The Chronology of its buildings in The Art Bulletin . Issue 45-2 (1963). P. 104.

- ^ A b c Henry Summerson: Stokesay Castle . Revised edition. English Heritage, London 2012. ISBN 978-1-84802-016-0 . P. 35.

- ^ A b c d RA Cordingley: Stokesay Castle, Shropshire: The Chronology of its Buildings in The Art Bulletin . Issue 45-2 (1963). P. 91.

- ^ Henry Summerson: Stokesay Castle . Revised edition. English Heritage, London 2012. ISBN 978-1-84802-016-0 . Pp. 35, 37.

- ^ John Britton: The Architectural Antiquities of Great Britain . Longman, Hurst, Rees and Orme, London 1814. p. 145.

- ^ A b Henry Summerson: Stokesay Castle. Revised edition. English Heritage, London 2012. ISBN 978-1-84802-016-0 . P. 37.

- ↑ a b c d e f g Gill Chitty, David Baker: The Tradition of Historic Consciousness: The Case of Stokesay Castle in Managing Historic Sites and Buildings . Routledge, Abington 1999. ISBN 978-1-135-64027-9 . P. 91.

- ↑ RA Cordingley: Stokesay Castle, Shropshire: The Chronology of its buildings in The Art Bulletin . Issue 45-2 (1963). P. 102.

- ^ Thomas Hudson Turner: Some Account of Domestic Architecture in England . Volume 1. James Parker, Oxford and London 1851.

- ^ A b c d Henry Summerson: Stokesay Castle . Revised edition. English Heritage, London 2012. ISBN 978-1-84802-016-0 . P. 38.

- ↑ a b It is difficult to accurately compare 19th century prices and incomes with modern prices or incomes. £ 103 can range from £ 8,825 to £ 233,300 in 2012 depending on the conversion factor used, and £ 215,000 totals between £ 16m and £ 329m

- ^ Michael Hall, The Victorian Country House: From the Archives of Country Life . Aurum, London 2010. ISBN 978-1-84513-457-0 . P. 146.

- ^ Henry Summerson: Stokesay Castle . Revised edition. English Heritage, London 2012. ISBN 978-1-84802-016-0 . P. 36.

- ↑ James D. La Touche: Stokesay Castle in Transactions of the Shropshire Archaeological and Natural History Society . Issue 1 (1878). Pp. 311-332.

- ^ A b Henry Summerson: Stokesay Castle . Revised edition. English Heritage, London 2012. ISBN 978-1-84802-016-0 . Pp. 38, 40.

- ^ A b c d e Henry Summerson: Stokesay Castle . Revised edition. English Heritage, London 2012. ISBN 978-1-84802-016-0 . P. 40.

- ^ History of Stokesay Court . Stokesay Court. Retrieved July 10, 2015.

- ^ A b Gill Chitty, David Baker: The Tradition of Historic Consciousness: The Case of Stokesay Castle in Managing Historic Sites and Buildings . Routledge, Abington 1999. ISBN 978-1-135-64027-9 . P. 92.

- ^ A b Gill Chitty, David Baker: The Tradition of Historic Consciousness: The Case of Stokesay Castle in Managing Historic Sites and Buildings . Routledge, Abington 1999. ISBN 978-1-135-64027-9 . Pp. 92-94.

- ↑ a b c Shropshire HER . Heritage Gateway. Retrieved July 10, 2015.

- ↑ Visitor Attraction Trends in England, 2010 . Visit England. Retrieved July 10, 2015.

- ^ Gill Chitty, David Baker: The Tradition of Historic Consciousness: The Case of Stokesay Castle in Managing Historic Sites and Buildings . Routledge, Abington 1999. ISBN 978-1-135-64027-9 . P. 86.

- ^ A b c Henry Summerson: Stokesay Castle . Revised edition. English Heritage, London 2012. ISBN 978-1-84802-016-0 . P. 3.

- ^ Norman John Greville Pounds: The Medieval Castle in England and Wales: A Social and Political History . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1994. ISBN 978-0-521-45828-3 . Pp. 279-281.

- ^ A b Henry Summerson: Stokesay Castle . Revised edition. English Heritage, London 2012. ISBN 978-1-84802-016-0 . Pp. 6-7.

- ↑ RA Cordingley: Stokesay Castle, Shropshire: The Chronology of its buildings in The Art Bulletin . Issue 45-2 (1963). P. 94.

- ^ A b Henry Summerson: Stokesay Castle . Revised edition. English Heritage, London 2012. ISBN 978-1-84802-016-0 . P. 22.

- ^ Robert Liddiard: Castles in Context: Power, Symbolism and Landscape, 1066-1500 . Windgather Press, Macclesfield 2005. ISBN 0-9545575-2-2 . P. 45.

- ↑ The historian Henry Summerson doubts that the moat was filled with water in the 13th century. He points out that there is no evidence that the trench was lined with clay - this would have improved its water tightness - and believes that archaeological excavations are the only way to determine the original condition of the trench. The historian Robert Liddiard and the head of the excavations, Michael Watson, believe that the moat was filled with water because there were other bodies of water around the castle.

- ^ OH Creighton: Castles and Landscapes: Power, Community and Fortification in Medieval England . Equinox, London 2002. ISBN 978-1-904768-67-8 . P. 81.

- ^ Nikolaus Pevsner: The Buildings of England: Shropshire . Penguin Books, London 2000 (1958). ISBN 978-0-14-071016-8 . P. 296.

- ^ Gill Chitty, David Baker: The Tradition of Historic Consciousness: The Case of Stokesay Castle in Managing Historic Sites and Buildings . Routledge, Abington 1999. ISBN 978-1-135-64027-9 . P. 88.

- ^ A b Henry Summerson: Stokesay Castle . Revised edition. English Heritage, London 2012. ISBN 978-1-84802-016-0 . P. 5.

- ^ A b c Henry Summerson: Stokesay Castle . Revised edition. English Heritage, London 2012. ISBN 978-1-84802-016-0 . Pp. 19-20.

- ↑ a b RA Cordingley: Stokesay Castle, Shropshire: The Chronology of its buildings in The Art Bulletin . Issue 45-2 (1963). P. 96.

- ↑ RA Cordingley: Stokesay Castle, Shropshire: The Chronology of its buildings in The Art Bulletin . Issue 45-2 (1963). P. 92.

- ^ Henry Summerson: Stokesay Castle . Revised edition. English Heritage, London 2012. ISBN 978-1-84802-016-0 . P. 20.

- ^ Henry Summerson: Stokesay Castle . Revised edition. English Heritage, London 2012. ISBN 978-1-84802-016-0 . Pp. 6-8.

- ^ Henry Summerson: Stokesay Castle . Revised edition. English Heritage, London 2012. ISBN 978-1-84802-016-0 . Pp. 8-9.

- ↑ a b RA Cordingley: Stokesay Castle, Shropshire: The Chronology of its buildings in The Art Bulletin . Issue 45-2 (1963). P. 99.

- ^ A b Henry Summerson: Stokesay Castle . Revised edition. English Heritage, London 2012. ISBN 978-1-84802-016-0 . P. 9.

- ^ Henry Summerson: Stokesay Castle . Revised edition. English Heritage, London 2012. ISBN 978-1-84802-016-0 . P. 8.

- ^ Henry Summerson: Stokesay Castle . Revised edition. English Heritage, London 2012. ISBN 978-1-84802-016-0 . P. 16.

- ^ A b Henry Summerson: Stokesay Castle . Revised edition. English Heritage, London 2012. ISBN 978-1-84802-016-0 . P. 17.

- ^ Henry Summerson: Stokesay Castle . Revised edition. English Heritage, London 2012. ISBN 978-1-84802-016-0 . P. 18.

- ^ A b Henry Summerson: Stokesay Castle . Revised edition. English Heritage, London 2012. ISBN 978-1-84802-016-0 . Pp. 11-12.

- ^ Henry Summerson: Stokesay Castle . Revised edition. English Heritage, London 2012. ISBN 978-1-84802-016-0 . P. 14.

- ^ Henry Summerson: Stokesay Castle . Revised edition. English Heritage, London 2012. ISBN 978-1-84802-016-0 . P. 10.

- ^ Gill Chitty, David Baker: The Tradition of Historic Consciousness: The Case of Stokesay Castle in Managing Historic Sites and Buildings . Routledge, Abington 1999. ISBN 978-1-135-64027-9 . P. 87.

- ^ OH Creighton: Castles and Landscapes: Power, Community and Fortification in Medieval England . Equinox, London 2002. ISBN 978-1-904768-67-8 . P. 83.

- ^ Norman John Greville Pounds: The Medieval Castle in England and Wales: A Social and Political History . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1994. ISBN 978-0-521-45828-3 . P. 188.

- ^ A b Robert Liddiard: Castles in Context: Power, Symbolism and Landscape, 1066-1500 . Windgather Press, Macclesfield 2005. ISBN 0-9545575-2-2 . Pp. 44-46.

- ^ A b Robert Liddiard: Castles in Context: Power, Symbolism and Landscape, 1066-1500 . Windgather Press, Macclesfield 2005. ISBN 0-9545575-2-2 . P. 46.

Web links

- Stokesay Castle . English Heritage.

Coordinates: 52 ° 25 ′ 49.1 " N , 2 ° 49 ′ 52.7" W.