Stourbridge Lion

| Stourbridge Lion | |

|---|---|

|

The first voyage of the Stourbridge Lion as portrayed by Clyde Osmer DeLand about 1916

|

|

| Number: | 4th |

| Manufacturer: | Foster, Rastrick and Company , Stourbridge , England |

| Year of construction (s): | 1828 |

| Retirement: | 1828, dismantled 1849 |

| Type : | B n2 |

| Gauge : | 1295 mm |

| Friction mass: | 7.1 t |

| Wheel set mass : | 3.9 t |

| Driving wheel diameter: | 1244 mm |

| Number of cylinders: | 2 |

| Cylinder diameter: | 215 mm |

| Piston stroke: | 914 mm |

| Cup length: | 3.2 m |

| Grate area: | 0.74 m² |

| Service weight of the tender: | 2.6 t |

The Stourbridge Lion was a steam locomotive operated by the Delaware and Hudson Canal Company . The name of the locomotive is derived from Stourbridge , the headquarters of the manufacturer Foster, Rastrick and Company , and the lion's face painted on the front of the boiler .

The Stourbridge Lion had taken an unladen test drive in Pennsylvania on August 9, 1829 , which is considered to be the first drive of a steam locomotive intended for commercial use in the United States . The Stourbridge Lion and the three sister locomotives never went into commercial service because they were too heavy for the rail company's routes.

history

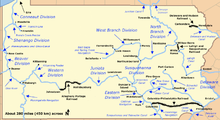

One of the oldest railways in the United States was operated by the Delaware & Hudson Canal Company, later the Delaware and Hudson Railway . 1823, the Company received the task of a rail link between New York City and the coal fields in Carbondale (Pennsylvania) channels to build and operate. The coal was initially supposed to be transported entirely by water, but as early as 1825 the engineers of the Delaware & Hudson Canal Company thought of rail transport for the first 25 km of the route, which lead through the hilly terrain of the Moosic Mountains . The west end of the canal was therefore not planned in Carbondale, but in Honesdale (Pennsylvania) , where the coal should be transferred from the railroad to the canal ships.

John B. Jervis , who later invented the 2'A Jervis wheel arrangement , was appointed chief engineer of the Delaware & Hudson Canal Company in 1827 . He planned eight inclined rope levels and three horizontal sections for the railway line, which should be operated with locomotives. The company's board of directors was well-disposed towards Jervis’s plan, but hesitated a little in implementing it because they had no experience with the then new railway technology.

In 1828 Horatio Allen , a former employee of Jervis, traveled to England to become familiar with railway technology. Allen received the order from Jervis to buy the locomotives and rails for the planned railway. Allen wrote back in July that he had ordered four locomotives for the railroad - three from Foster, Rastrick and Company, and one from Robert Stephenson and Company .

The Pride of Newcastle developed by Robert Stephenson reached the United States on January 15, 1829, the Stourbridge Lion developed by John Urpeth Rastrick four months later, on May 13, 1829. About the other two Rastrick locomotives named Hudson and Delaware are no further details known.

The locomotive was reassembled in the West Point Foundry in New York State after it was transported across the Atlantic, tested with the wheels in the air and tested with steam from the factory and demonstrated to the interested public. After another transport to Honesdale, Pennsylvania, there was a much-noticed test drive with the Stourbridge Lion on August 8, 1829. The locomotive worked well, but destroyed the tracks it traveled on. The tracks, which were designed for 4-ton vehicles, were not able to cope with the 7.5-ton locomotives, which is why they were shut down after another test run on September 9th.

Remaining and preserved parts

A letter dated 1834 shows that the railway company tried to sell the locomotives but failed. They seemed unsuitable for the new railways and already out of date with their balance lever drive mechanism . In addition, American manufacturers built their own locomotives with a more suitable design as early as 1830. The four Delaware and Hudson Canal Company locomotives therefore served only as wrought iron donors until the mid-1840s. In 1845 all that remained was the Stourbridge Lion's boiler , which was used in the John Simpson foundry in Carbondale for five years for a stationary steam engine before the owner moved to the west coast and sought his fortune in the California gold rush .

The foundry was sold to new owners a few years later, who continued to use the boiler until 1871, before attempting to sell the boiler, which is now over 40 years old, as a historically valuable object for $ 1,000 in 1874. The sale did not succeed, but the boiler was shown at the 1883 National Railway Technology Exhibition in Chicago by the Delaware and Hudson Canal Company, with many boiler fittings being stolen on the way to the exhibition or at the exhibition itself by souvenir hunters, sometimes with the help of sledgehammers and chisels . Early, the owner of the cauldron, tried to make a profit from that by exhibiting the torso in Scranton and charging 10 cents a head for viewing. The business failed, and the kettle entered the Smithsonian Institution's collection in 1890 along with a cylinder, two balance levers, and four wheel tires . The wheel tires could also belong to the Pride of Newcastle , which had the same drive wheel set diameter . At the Centennial Exhibition of 1876, the wheel tires were exhibited together with the crank rings of this locomotive.

The Smithsonian Institution tried to rebuild the locomotive using the existing parts, but the company failed because only a few parts had been preserved that could not even be clearly assigned to the Stourbridge Lion . The parts were on display for a while in the Transport Hall at the National Museum of American History in Washington, DC , before being loaned to the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad Museum in Baltimore , where they can be seen along with a model of the locomotive.

Disputing the first trip

It is not certain that the Stourbridge Lion's journey was actually a locomotive's first journey on the train. According to some sources, the first Pride of Newcastle voyage may have been closed to the public. Little is known of this locomotive, although it arrived in America before the Stourbridge Lion . On the recommendation of Horatio Allen, it should be used on the horizontal stretch over the vertex of the connection. There is a presumption that the locomotive was tested without an audience on July 26th, 1829 and that it was found either that the locomotive was unsuitable for operation or that a boiler explosion occurred which destroyed the locomotive.

In 1981 a small coffin-shaped wooden box was found at a New York antique dealer with the inscriptions John B. Jervis, 1829, D&H Canal Company on one side, America on the other side and Blew up July 26, 1829. on the inside of the lid. Further information about the incident is not known. It is believed that the Delaware and Hudson Canal Company tried to cover up the incident to prevent the company's stock price from collapsing.

Replica

The Delaware and Hudson Railroad built a working replica of the Stourbridge Lion in 1932 , with - as with the original - all iron parts were forged by hand. The replica was shown at the 1933 A Century of Progress Exhibition in Chicago and is now on display at the Honesdale Museum of the Wayne County Historical Society .

technical description

The locomotive had a simple flame tube boiler without a smoke chamber . The chimney led to the outside through the boiler roof at the end of the flame tube. The exhaust lines of the cylinders were led up at the front of the boiler, connected with a T-piece and fed to the blowpipe in the chimney.

The drive of the locomotive consisted of two balancing machines , the cylinders of which were attached to the left and right at the rear end of the boiler. The drive rods were attached near the piston rods at the rear ends of the balance levers and drove the wheels of the rear axle of the locomotive. Coupling rods connected the two sets of wheels.

The wheels of the locomotive had spokes and rims made of wood, only the hub was made of cast iron and the spoke on which the coupling rod attached was made of wrought iron. For the first time on a locomotive, counterweights were used in the wheels of the drive axle.

Instead of a tender , a coal wagon with water supplies was carried. The water was carried into the boiler by piston pumps that were driven by a rod from the balance levers. In order to preheat the water, it was first gravity fed into a container under the boiler, through which the cylinder's exhaust pipes were led. It may have been one of the oldest uses of a feed water preheating system on a steam locomotive.

Agenoria

After the three locomotives destined for America, Foster, Rastrick and Company built another locomotive of the same type in 1829. It was named Agenoria and was used on the Kingswinford Railway , also called Shutt End Railway , where it was used on the 3 km long connection between two inclined cable levels. It is now on display at the National Railway Museum in York, England.

literature

- Brian Hollingsworth: The Illustrated Directory of Trains of the World . MBI Publishing Company, 2000, ISBN 0-7603-0891-8 , Stourbridge Lion 0-4-0, pp. 14–15 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

Web links

- The Stourbridge Lion. Bridge Line Historical Society, accessed October 15, 2013 .

- The Stourbridge Lion. stourbridge.com, accessed October 15, 2013 (page from Storebridge, England containing information on Foster, Rastrick and Company).

- Railroads America - The Stourbridge Lion And Tom Thumb. In: Old and Sold. 1927, accessed October 15, 2013 .

Individual evidence

- ^ A b c d e f John H. White: A History of the American Locomotive: Its Development, 1830-1880 . Courier Dover Publications, 1979, ISBN 0-486-23818-0 , pp. 239–245 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ^ A b Karl Zimmermann: The Stourbridge Lion: America's First Locomotive . 2012, ISBN 978-1-59078-859-2 (English).

- ^ William H. Brown: The history of the first locomotives in America. From original documents, and the testimony of living witnesses . Appleton and Company, New York 1871, XIII: First English Locomotives, pp. 74-78 ( link ).

- ↑ HistoryWired: A few of our favorite things. Historywired.si.edu, accessed July 29, 2010 .

- ^ Andrew Naylor: Stourbridge Lion Exhibit in Baltimore & Ohio Railroad Museum, Baltimore. In: Andrew Naylor's trains. October 12, 2010, accessed October 17, 2013 (picture of the items on display in the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad Museum).

- ↑ a b Christopher T. Baer: 1829. (PDF; 37 kB) (No longer available online.) In: A general chronology of the Pennsylvania Railroad Company its predecessors and successors and its historical context. 2005, archived from the original on October 14, 2013 ; Retrieved October 17, 2013 . Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ J. Demos, R. Thayer: The Case Of The Vanishing Locomotive ... And The Birth Of The Railroad Revolution In America. A mystery solved. In: American Heritage . tape 49 , no. 6 , 1998, pp. 91-95 .

- ^ John H. Lienhard: A lost locomotive. In: Engines of Our Ingenuity. KUHF-FM Houston, 2006, accessed October 17, 2013 .

- ^ The Stourbridge Lion and the Birthplace of America's Commercial Railroad. (No longer available online.) Wayne County Historical Society, archived from the original on May 2, 2015 ; accessed on October 17, 2013 (English).

- ^ Opening of the new Kingswinford Railway on the Staffordshire and Worcestershire Canal. In: Polytechnisches Journal . 33, 1829, Miszelle 12, pp. 325-326.

- ↑ The Agenoria. In: Locomotives collection. National Railway Museum (York) , accessed October 16, 2013 .