Strigopidae

| Strigopidae | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Kaka , subspecies of the North Island |

||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||

|

||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||

| Strigopidae | ||||||||||

| Bonaparte , 1849 |

The Strigopidae are a family of parrots made up of two genera , Nestor and Strigops . The genus Nestor includes the Kea , the Kaka , the thin beak Nestor and Chatham Kaka , the genus whereas Strigops with a single type, the Kakapo , monotypic is.

All species are or have been endemic to New Zealand and the surrounding oceanic islands such as Chatham Island , Norfolk Island, and Phillip Island . The current names Kea, Kaka and Kakapo come from the Moro language .

The Norfolk kaka and the Chatham kaka became extinct in historical times, the kakapo, the kea, and both subspecies of the kaka are endangered. The extinctions of the two species, as well as the decline in the other three, were caused by human activity. European settlers introduced pigs and fox kusus , which ate the eggs of the ground-breeder . In addition, the birds were hunted by humans for food and as agricultural pests, lost their habitat and suffered from the introduction of wasps .

Systematics

Since there is still no consensus on the systematics of the parrots, the species of the Strigopidae have been assigned to different taxa. The family is one of the three parrot families recognized today, the other two being the cockatoos (Cacatuidae) and the true parrots (Psittacidae). It is divided into two tribes , the Nestorini and the Strigopini, each with only one genus Nestor with two species still alive today and two extinct species, although little is known of the Chatham kaka and Strigops with the kakapo as the only species. Traditional the species of the family Strigopidae are assigned to the real parrots, but various studies have shown their basal position at the origin of the parrot family tree. Most authors now see the group as an independent family, while others are in favor of the fact that the two tribes are each assigned to an independent family (Nestoridae and Strigopidae).

| Tribus Nestorini Bonaparte , 1849 - 1 genus - 4 species | ||||||

| Genus Nestor Parrots ( Nestor ) Lesson , 1830 - 1 Art | ||||||

| German name | Scientific name | distribution | Hazard level Red List of IUCN |

Remarks | image | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kea |

Nestor notabilis Gould , 1856 |

South Island New Zealand |

|

monotypically 48 cm long. With predominantly olive-green plumage; the under wing-coverts and the back are colored orange. The feathers have a dark border. Beak, legs and feet are dark brown. The male has a longer beak than the female. Habitat mountain forests and subalpine bushland, at altitudes of 850 to 1400 m. |

|

|

| South Island Kaka |

Nestor meridionalis meridionalis ( JF Gmelin , 1788) |

South Island New Zealand |

|

Similar to the North Island Kaka, but slightly smaller, with lighter colors, the top of the head is almost white, the beak is longer and more curved in the males. Habitat of untouched southern beech and stone beech forests at heights of 450 to 850 m in summer and 0 to 550 m in winter. |

|

|

| North Island- Kaka |

Nestor meridionalis septentrionalis Lorenz von Liburnau , 1896 |

North Island of New Zealand |

|

About 45 cm long. Mainly olive brown with dark feather edges. Under wing-coverts, tail and neck plumage are bright red, the cheeks are golden brown, the top of the head is greyish. Habitat of untouched southern beech and stone beech forests at heights of 450 to 850 m in summer and 0 to 550 m in winter. |

|

|

| Thin-beaked nest |

Nestor Productus Gould , 1836 |

Formerly endemic to Norfolk Island and Phillip Island |

|

monotypical About 38 cm long. Upper side olive-brown, cheeks and throat orange or reddish, breast orange-brown, thighs, rump and lower abdomen dark orange. Habitat rocks and trees |

|

|

| Chatham kaka |

Nestor chathamensis Wood , Mitchell , Scofield & Tennyson , 2014 |

Formerly endemic to the Chatham Islands |

Extinct between 1550 and 1700 | monotypic Known only from subfossil bones. Appearance unknown, bones indicate impaired flight ability. Forests as a habitat |

||

| Tribe Strigopini Bonaparte , 1849 - 1 genus 1 species | ||||||

| Genus Strigops G. R. Gray , 1845 - 1 species | ||||||

| German name | Scientific name | distribution | Hazard level Red List of IUCN |

Remarks | image | |

| Kakapo |

Strigops habroptila G. R. Gray , 1845 |

New Zealand: Maud , Chalky , Codfish and Anchor Islands |

|

monotypical Large, clumsy parrots, 58–64 cm long; Males larger than females, weighing 2 to 4 kg at sexual maturity. Mainly green with brown and yellow, the greenish-yellow undersides mottled. Face bright and owl-like. Habitat untouched southern beech and stone beech forests , subalpine scrubland, tussock grassland at heights of 10 to 1400 m. |

|

|

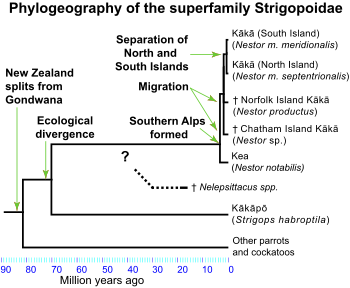

Phylogeography

The ancestors of the Strigopidae separated from the other parrots 82 million years ago when New Zealand broke off from Gondwana , resulting in the geographical isolation of the Strigopidae. The ancestors of the two genera Nestor and Strigops separated 60 to 80 million years ago. The mechanism is called allopatric speciation . Over time, the ancestors of the two surviving genera occupied different ecological niches . This led to sympatric speciation . In the Pliocene , about five million years ago, the formation of the New Zealand Alps changed the landscape and opened up new possibilities for speciation. Three million years ago, a group called the keas adapted to life at high altitudes, while the various forms of kakas remained in the lowlands. Both types of islands, the Norfolk kaka and the Chatham kaka, are the result of the immigration of a small group of individuals to the islands and the subsequent adaptation to the habitat of those islands. In the absence of Chatham kaka DNA, it is difficult to pinpoint exactly when those speciation processes occurred. The kaka populations of the North Island and the South Island became isolated from each other at the end of the Pleistocene, when sea levels rose from thawing glaciers.

Until recently, four-legged mammals did not live in New Zealand and the surrounding islands, an environment that has resulted in many birds becoming ground breeders and some birds losing their ability to fly.

Way of life

The three recent species of the family occupy quite different ecological niches, a result of the family's phylogeographical dynamics. The kakapo is a flightless bird, well camouflaged by its plumage, which lives nocturnal in order to avoid the large diurnal birds of prey. Usually it only breeds every 3 to 5 years when certain stone grapes such as the rimu ( Dacrydium cupressinum ) are bearing plenty of seeds.

Keas are well adapted for life at high altitudes and are regularly seen in the snow at the ski resorts. Since there are no trees in the alpine zone, they build their nests in caves in the ground.

Relationship with people

Meaning for the Māori

The Māori used the parrots in several ways. They hunted them for food, kept them as pets, and used their feathers to make clothes. The feathered hides of the kakapo were mainly used to make cloaks for the chiefs' wives and daughters. The feathers were also used to decorate the taiaha , a traditional Māori weapon.

Danger

Of the five species, the Norfolk kaka and the Chatham kaka became extinct in modern times. The last known Norfolk kaka died in captivity in London shortly after 1851, and only between 7 and 20 hides remain. The Chatham kaka became extinct between 1550 and 1700 after Polynesians colonized the island before Europeans even reached the island, and is known only from subfossil bones. Of the species still alive today, the kakapo is threatened with extinction with only 90 individual animals. The main islands kaka are critically endangered and the kea is listed as endangered.

New Zealand's fauna developed for a long time without the presence of humans or other mammals. Before human colonization, there were only a few species of bats and marine mammals, the only predators were birds of prey that hunt visually. These circumstances influenced the development of New Zealand's parrots, e.g. B. the development of flightlessness in the kakapo and the ground breeding of the kea. Polynesians reached the islands between 800 and 1300 and introduced the Kuri, a breed of dog. This was fatal for the native animals, as the Kuri can locate its prey by smell and the native animals had no defense against it.

The kakapo was hunted for its flesh, skin, and plumage. When the first European settlers came, it was still widespread. The large-scale clear-cutting of the forests and the scrubland destroyed its habitat, while the ground-dwelling, flightless birds were easy victims of imported carnivores and omnivores such as rats, cats and ermines .

The kaka requires large areas of forest to live, and the ongoing fragmentation for agricultural purposes has had a devastating effect on the species.

Another threat is the food competition with introduced species such as the fox kusu , which, like parrots, eats the seeds of mistletoe and ironwood , or with introduced wasps , which eat honeydew , which is important for parrots . Brooding females, young and eggs are particularly threatened by introduced predators.

protection

There are protection programs for the kakapo and the kaka while the kea population is monitored. Of the more than 100 kakapos living, each individual is known and all are part of a breeding and conservation program.

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c Christidis L, Boles WE: Systematics and Taxonomy of Australian Birds . CSIRO Publishing, Canberra 2008, ISBN 978-0-643-06511-6 , p. 200.

- ↑ a b c d Forshaw, Joseph M .; Cooper, William T. (1981) [1973, 1978]. Parrots of the World (corrected second edition ed.). David & Charles, Newton Abbot, London. ISBN 0-7153-7698-5 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g Millener, PR (1999). The history of the Chatham Islands' bird fauna of the last 7000 years - a chronicle of change and extinction. Proceedings of the 4th International meeting of the Society of Avian Paleontology and Evolution (Washington, DC, June 1996). Smithsonian Contributions to Paleobiology 89: 85-109. http://www.sil.si.edu/smithsoniancontributions/Paleobiology/sc_RecordSingle.cfm?filename=SCtP-0089 .

- ↑ Maori Bird Names . Kiwi Conservation Club , January 2001, archived from the original on April 13, 2009 ; accessed on May 16, 2019 (English, original website no longer available).

- ↑ a b c Nestor productus in the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2011.2. Listed by: Birdlife International, 2008. Retrieved November 19, 2011.

- ↑ a b c Strigops habroptila in the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2011.2. Posted by: Birdlife International, 2010. Retrieved November 19, 2011.

- ↑ a b c d Nestor meridionalis in the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2011.2. Listed by: Birdlife International, 2008. Retrieved November 19, 2011.

- ↑ a b c Nestor notabilis in the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2011.2. Listed by: Birdlife International, 2008. Retrieved November 19, 2011.

- ↑ a b Threats to kākāpō . Department of Conservation , archived from the original on April 4, 2009 ; accessed on May 16, 2019 (English, original website no longer available).

- ↑ a b Threats to kākā . Department of Conservation , archived from the original on December 31, 2008 ; accessed on May 16, 2019 (English, original website no longer available).

- ↑ Threats to kea . Department of Conservation , archived from the original on October 4, 2009 ; accessed on May 16, 2019 (English, original website no longer available).

- ↑ For information on older systematic positions, see Charles Gald Sibley, Jon E. Ahlquist: Phylogeny and Classification of Birds . Yale University Press, 1991. For more recent taxonomies, see Christides.

- ↑ a b T.F. Wright, Schirtzinger EE, Matsumoto T., Eberhard JR, Graves GR, Sanchez JJ, Capelli S., Muller H., Scharpegge J., Chambers GK & Fleischer RC: A Multilocus Molecular Phylogeny of the Parrots (Psittaciformes): Support for a Gondwanan Origin during the Cretaceous . In: Mol Biol Evol . 25, No. 10, 2008, pp. 2141-2156. doi : 10.1093 / molbev / msn160 . PMID 18653733 .

- ^ Masayoshi Tokita, Takuya Kiyoshi, Kyle N. Armstrong : Evolution of craniofacial novelty in parrots through developmental modularity and heterochrony . In: Evolution & Development . Volume 9, Issue 6 , November / December , 2007, pp. 590-601 , doi : 10.1111 / j.1525-142X.2007.00199.x (English, abstract ).

- ↑ RS de Kloet, de Kloet SR: The evolution of the spindlin gene in birds: Sequence analysis of an intron of the spindlin W and Z gene reveals four major divisions of the Psittaciformes . In: Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution . 36, 2005, pp. 706-721. doi : 10.1016 / j.ympev.2005.03.013 .

- ^ Bradley C. Livezey, Richard L. Zusi : Higher order phylogeny of modern birds (Theropoda, Aves: Neornithes) based on comparative anatomy. II. Analysis and discussion . In: Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society . Volume 149, Issue 1 , January 2007, pp. 1–95 , doi : 10.1111 / j.1096-3642.2006.00293.x (English, abstract ).

- ^ DG Homberger: Classification and the status of wild populations of parrots . In: Luescher AU (Ed.): Manual of parrot behavior . Blackwell Publishing, Ames (IA) 2006, ISBN 978-0-8138-2749-0 , pp. 3-11.

- ↑ a b Kea - BirdLife Species Factsheet . BirdLife International. 2008. Retrieved February 16, 2011.

- ↑ a b c d e Tony Juniper, Mike Parr: Parrots: A Guide to Parrots of the World . Yale University Press, 1998, ISBN 978-0-300-07453-6 .

- ↑ a b c Kaka - BirdLife Species Factsheet . BirdLife International. 2008. Retrieved February 16, 2011.

- ↑ a b Norfolk Island Kaka - BirdLife Species Factsheet . BirdLife International. 2008. Retrieved February 16, 2011.

- ↑ a b Kakapo - BirdLife Species Factsheet . BirdLife International. 2008. Retrieved February 16, 2011.

- ^ EJ Grant-Mackie, JA Grant-Mackie, WM Boon & GK Chambers: Evolution of New Zealand Parrots . In: NZ Science Teacher . 103, 2003.

- ↑ Miriama Evans, Ranui Ngarimu, Creative New Zealand, Norman Heke: The Art of Māori Weaving . Huia Publishers, Wellington, NZ 2005, ISBN 978-1-86969-161-5 .

- ↑ Kahu huruhuru (feather cloak) . In: Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa . Retrieved December 31, 2008.

- ↑ a b c d Rob Tipa: Kakapo in Māori lore . In: Notornis . 53, 2006, pp. 193-194.

- ↑ James Cowan Greenway: Extinct and Vanishing Birds of the World , 2nd. Edition, Dover Publications, New York 1967.

- ↑ Psittacidae . Zoological Museum Amsterdam , archived from the original on June 8, 2011 ; accessed on May 16, 2019 (English, original website no longer available).

- ↑ Psittacidae (Parrots) . In: Naturalis. Nationaal Natuurhisttorisch Museum , archived from the original on June 8, 2011 ; accessed on May 16, 2019 (English, original website no longer available).

- ↑ Douglas G. Sutton (ed.): The Origins of the First New Zealanders . Auckland University Press, Auckland 1994, ISBN 1-86940-098-4 .

- ↑ DOC's Kakapo work with . Department of Conservation , archived from the original on April 4, 2009 ; accessed on May 16, 2019 (English, original website no longer available).

- ↑ DOC's Kākā work with . Department of Conservation , archived from the original on December 31, 2008 ; accessed on May 16, 2019 (English, original website no longer available).

- ↑ DOC's Kakapo work with . Department of Conservation , archived from the original on October 4, 2009 ; accessed on May 16, 2019 (English, original website no longer available).