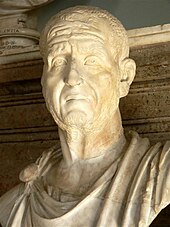

Decius (emperor)

Gaius Messius Quintus Traianus Decius (* about 190 or 200 / 201 in Budalia at Sirmium , today Sremska Mitrovica in the Roman province of Pannonia inferior ; † the first half of June 251 at Abrittus , today Razgrad in Bulgaria) was emperor of the Roman Empire of 249 to 251, the first in a long line of able men from the Illyrian provinces . However, in contrast to most of the later “ Illyrian emperors ” , Decius had already succeeded in advancing to the Senate; his family obviously belonged to the imperial aristocracy and, unlike many later rulers, he did not come from a simple background.

Life

Ascent

As with many other soldier emperors of the 3rd century, the date of birth of Decius is unknown. Usually 200 or 201 is given as the year of birth. However, according to Malalas , he should have been around 60 years old at the time of his death (251), according to which a year of birth would have to be assumed around 190. Decius' family had probably achieved the rise to the nobility in the course of the 2nd century .

In 232 Decius held the highest senatorial office under Emperor Severus Alexander with the consulate , albeit only as a suffect consul . Then he officiated as governor in the provinces of Germania inferior (Lower Germany), Moesia ( Moesia ) and Hispania citerior ( Tarragonensia ). During the six-emperor year 238 he seems to have been loyal to Maximinus Thrax , but to have survived his fall unscathed. Moreover, at an unknown point in time, he was in the particularly prestigious position of praefectus urbi of Rome. Around 246 Decius was entrusted by Emperor Philip Arabs as Dux with an important command on the Danube . After he had received the order in autumn 248 to put down a military revolt under Pacatianus in Moesia and Pannonia , he was allegedly urged by his soldiers in 249 (or already towards the end of 248) to accept the imperial title. Decius probably became a usurper on his own initiative : he continued to ostentatiously point out his loyalty to Philip, but at the same time marched resolutely with his troops, thereby exposing the Danube border , to Italy. When the emperor finally proceeded against Decius, he was defeated by him in the autumn of 249 near Verona in an extremely bloody battle. Philip met his death and became subject to the damnatio memoriae . After his now official appointment as emperor by the Senate, Decius raised his wife Herennia Cupressenia Etruscilla to Augusta (Empress).

War against the Goths

During his short reign, Decius was mainly engaged in important military operations against the Goths , who had been pressing the Danube border for some time (see also Imperial Crisis of the 3rd Century ). After the withdrawal of troops 249, these had crossed the Danube and overran the provinces of Moesia and Thracia (Thrace). Further details are unknown; Jordanes speaks of 70,000 attackers, but this is probably overstated. But even the part that Decius and his son Herennius Etruscus had in the following campaign is unclear, because the sources of Decius' reign are - as with most of the other soldier emperors - very poor.

Decius gathered an army and, together with his son and co-emperor Herennius, went personally against the enemies (his younger son Hostilian stayed in Rome). The Goths were apparently surprised by Decius during the siege of Nicopolis on the Danube. On its approach they crossed the Balkan Mountains and attacked Philippopolis . Decius followed them, but a heavy defeat at Beroë , today's Stara Sagora , made it impossible for him to save Philippopolis, which fell into the hands of the Goths, who treated the city with devastating cruelty. Their commander, Priscus , declared himself emperor under Gothic protection. A new parchment find (from the so-called Scythica Vindobonensia and probably from the work of Dexippus ) also reveals the leader of the Goths, a certain Ostrogotha .

The siege of Philippopolis had so exhausted the number and strength of the Goths that they offered to hand over their booty and their captives on condition of free withdrawal. But Decius had finally succeeded in encircling them, and now he hoped to cut off their retreat and achieve a decisive victory. He refused to negotiate. The last skirmish, in which the Goths fought with the courage of desperation, took place on the swampy soil of the Dobrudscha near Abrit (t) us ( Battle of Abrittus ) or Forum Trebonii .

Jordanes (6th century) reports in its Gothic history , that Decius' son Herennius was killed at the beginning of the battle by an arrow, and the Emperor then exclaimed:

- “ Let us not mourn anyone; the death of a soldier is not a great loss to the state. "(Jordanes, Getica 18,101)

Probably this episode is unhistorical. In any case, the Roman army was destroyed in this battle due to tactical errors and Decius was slain. After the news of the fall of the two emperors reached the capital in June 251, the Senate decided that father and son were elevated to the rank of gods ( Divus ) after Decius' younger son Hostilian had been elevated to Augustus . However, there are indications that a little later, after Hostilian's untimely death in November of the same year (251), like his predecessor Philip, the memory of Decius fell into a damnatio memoriae , perhaps because he was held responsible for the military catastrophe.

Domestic and religious policy

Decius was initially successful militarily and was considered a capable and experienced administrator. At the beginning of the year 250 he issued a general offer of sacrifice, which perhaps aimed at restoring the mos maiorum and thus the ancient Roman religion , but perhaps also only served as a demonstration of loyalty for the new emperor after the end of the bloody civil war. Every inhabitant of the Imperium Romanum had to appear before a commission to make sacrifices. A certificate (libellus) was issued for the executed victim .

Those who refused to sacrifice to the emperor and the Roman gods could be arrested and tortured as an enemy of the state, sentenced to forced labor, deprivation of property, exile or death. “With a little skill, [these» libelli «also] could be sneaked out […] without having to sacrifice themselves. In the church language, those were the so-called libellatici. ”Due to old privileges, only the Jews were allowed to pray for the emperor and empire instead .

For the Christians , however, sacrifice was problematic because it was not compatible with their faith; Of course, this did not change the fact that Christian soldiers could also be loyal to the emperor. But it was only through the demonstrative refusal of some (by far not all) Christians that the Roman authorities became aware of the problematic attitude of the followers of this religion. A general and sometimes very bloody persecution of Christians soon ensued , during which the Greek scholar Origen was tortured and the Roman bishop Fabianus was executed (see also Minias of Florence ). Christians who showed themselves ready to sacrifice to the emperor, however, were spared. The large number of these "fallen" (lapsi) led to violent disputes within the communities after the end of the persecution (see also heretic controversy ).

Either as a concession to the Senate or perhaps with the ulterior motive of improving public morale, Decius reportedly sought to revive the office and authority of the censor . The choice was left to the Senate , which is said to have unanimously chosen Valerian , the future emperor. But Valerian, who knew exactly the dangers and difficulties associated with this office at this time, declined the responsibility. The invasion of the Goths and the death of Decius put an end to the attempt, which is only mentioned in the highly unreliable Historia Augusta .

literature

- Gustav Schoenaich: The Libelli and their significance for the persecution of Christians by the Emperor Decius. Breslau 1910. ( digitized version )

- Augustinus Bludau: The Egyptian Libelli and the persecution of Christians of the Emperor Decius. Herder, Freiburg i.Br. 1931.

- HA Pohlsander: The Religious Policy of Decius. In: Rise and Fall of the Roman World . Part 2: Principate . Vol. 16: Religion . Teilbd. 3: Paganism: Roman religion, general . de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1986, pp. 1826–1842.

- Anthony R. Birley : Decius Reconsidered. In: E. Frézouls, H. Jouffroy (eds.): Les empereurs illyriens. Actes du colloque de Strasbourg (11-13 October 1990) organized by the Center de Recherche sur l'Europe centrale et sud-orientale. Strasbourg 1998, pp. 57-78.

- JB Rives: The Decree of Decius and the Religion of Empire. In: Journal of Roman Studies 89, 1999, pp. 135–154.

- Bruno Bleckmann: On the motives for the persecution of Christians by Decius. In: Klaus-Peter Johne et al. (Ed.): Deleto paene imperio Romano. Stuttgart 2006, pp. 57-71.

Web links

- Literature by and about Decius in the catalog of the German National Library

- Geoffrey Nathan and Robin McMahon: Short biography (English) at De Imperatoribus Romanis (with references).

Remarks

- ^ Alfred Heuss : Roman history. Westermann Verlag, Braunschweig 1960, p. 421.

| predecessor | Office | successor |

|---|---|---|

| Philip Arabs |

Roman emperor 249–251 |

Trebonianus Gallus |

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Decius |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Decius, Gaius Messius Quintus Traianus; Traianus Decius, Gaius Messius Quintus |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | roman emperor |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 190 or 201 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Budalia at Sirmium |

| DATE OF DEATH | 251 |

| Place of death | Abrittus |