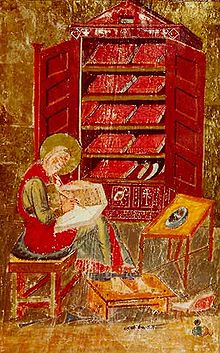

Esra (person)

Ezra ( Hebrew עֶזְרָא 'Ezrā ) was, according to the biblical account of the Old Testament, a priest and descendant of the first high priest Aaron . His name means " YHWH helps" or "God is help". After the time of the Babylonian exile, he lived in the Persian empire and belonged to the Jewish community, some of which still lived in Babylon, but had already returned to a large extent to the Persian province of Jehud through the edict of Cyrus . Esra held the office of "State Secretary" for religious affairs of the Jews at the Persian court. Equipped with powers of attorney, Ezra moved around 458 BC. To Jerusalem . He is mentioned in the book Esra from chapter 7 EU . Esra's concern was to restore law and order in the newly formed Jerusalem community. Esra's authority was over the entire 5th satrapy of the Persian Empire. It authorized him to appoint judges in all Jewish communities. This was also true of the Samaritans who lived around Jerusalem and were hostile to it. He is likely to have had a significant influence on the selection and editing of the holy scriptures and the Mosaic law.

The biblical tradition

The books of Ezra and Nehemiah describe this phase in Israel's history.

Ezra is sent to Jerusalem by the Persian king Artaxerxes to restore the order of the God of Israel there . With him another 1496 people return to Ezra 8.1-14 EU . He orders priesthood and temple service and organizes the return of more Jews from exile.

From Ezra 7.27–28 EU the book changes from the Aramaic to the Hebrew language and to the first person . This sudden change reveals the autobiographical nature of the report.

He is dismayed by marriages with pagan women and asks God for mercy. Finally, these marriages break up.

'Uzair

In the Qur'an , a male person named 'Uzair was mentioned in a late Medinan verse . Due to the lack of further Quranic information, it was difficult to identify 'Uzair with any particular historical or legendary person. Muhammad Madjdi Bey wanted to see the ancient Egyptian male deity Osiris in 'Uzair . Paul Casanova recognized in him the angelic being Uzail-Azael ( Asasel ). Both attempts at identification could, however, be rejected with good justification. Otherwise, many Koran scholars saw and still see the biblical person named Esra in the Koranic 'Uzair.

“The Jews say, 'Uzair is the Son of Allah,' and the Christians say, 'Al-Masih is the Son of Allah.' These are their words from their [own] mouths. They use similar words to those who previously disbelieved. Allah fight them! How they let themselves be turned away! "

“[On Judgment Day ] it will be said to the Jews: 'What were you used to worshiping?' They will answer, 'We were used to worshiping' Uzair, the son of Allah. ' It will be said to them: 'You are liars, for Allah has neither a wife nor a son. What do you want [now]? ' They will answer, 'We want you to provide us with water.' They will then be told, 'Drink.' And they will fall [instead] down to Hell . "

Both the Quran verse and the hadith mentioned above claim that the Jews would have binitarian monotheism . Both passages of the text could say that the Jews - that is, all Jews at all times - would believe in two divine beings. In exactly this way the verses were interpreted several times. On the other hand, the Koranic choice of words does not explicitly break down whether all Jews or only certain Jews claimed that Ezra was the Son of God. The verb used is used in the singular and the noun remains undefined ( waqālati l-yahūdu ). In addition, a clarifying word such as “all” or “all” ( kulli , bikulli ) is missing . The lines simply say that Jews, in addition to their real and only deity, would also believe in Ezra, as the Son of God ( 'Uzair ibn Allah) . The assertion of binitarian Jewish monotheism can be rejected for rabbis in the context of the Palestinian Talmud , for many rabbis in the context of the Babylonian Talmud , for the Jewish philosophers of the Middle Ages and for practically all Judaism from the 19th century onwards. However, this does not rule out the presence of temporally and spatially limited Jewish currents that deviated from strict Unitarian monotheism. In fact, there is a whole series of textual references to this in the Jewish literature from the time during and shortly after the second YHWH Temple in Jerusalem.

Furthermore, a story was passed down by al-Muqaddasī that supposedly came from Palestine. In it, a group of Palestinian Jews quarreled with a group of Palestinian Christians. The Jews replied to the Christians that it was not Jesus of Nazareth but Ezra who was the Son of God. Salih al-Hashimi named such a Palestinian Jewish group al-Mu'tamaniyyah . Whether the al-Mu'tamaniyyah really existed historically, however, can be highly doubted. For it was precisely Palestinian Judaism who tried very hard to differentiate itself from the Christians living in the same place, who believed in a Son of God.

At-Tabarī wrote that a Jew named Phinehas may have told the Islamic prophet Mohammed that Ezra was the Son of God. Rhazes reported something similar about three (nameless) Jews. Both authors suggested that at the time of Muhammad a Jewish movement that had long since disappeared and who worshiped Ezra as the Son of God might have lived in his environment. The Semitist Mark Lidzbarski agreed with this opinion. Another story goes back to ʿAbdallāh ibn ʿAbbās . He said that the Jews once forgot their Torah. But it would have been brought back to them by Ezra. Ibn ʿAbbās' story was probably based on a specific section of text in the fourteenth chapter of the apocryphal Jewish Book of Ezra . Ibn ʿAbbās said that following the return of the Torah, the Jews began to speak of Ezra as the Son of God.

There is no question that Ezra is revered among the Jews to this day. It was thanks to the Persian State Secretary of Jewish descent that a version of the Torah was presented in its present form and for the first time in Aramaic square script. Because of this work, Ezra was born around the year 500 C.E. Z. placed on a par with Moses in the Babylonian Talmud. The Syriac version of the already mentioned 4th book of Ezra went even further.

“It was then that Ezra was raptured and taken into the place of his comrades after having written [94 holy Jewish books]. He is called 'the writer of the science of the Most High in eternity'. "

According to these two verses, Ezra did not die on earth, but was raptured by his deity beforehand. There he was given the title of scribe of the Science of the Most High . Both facts paralleled Ezra with the seventh of the legendary biblical patriarchs named Enoch . According to the biblical book of Genesis , Enoch did not die on earth either, but was raptured from his divinity beforehand. There, according to the Ethiopian Book of Enoch, he was given the title of scribe of justice . Finally, in the 71st chapter of the book, the rapt patriarch was transformed into godlike Son of Man . Examples are now known from verses of the New Testament in which older godly personalities were equated with younger ones. According to those verses, first-century Palestinian Jews believed it. At the moment it is quite possible that Jesus of Nazareth would either be the returned prophet Elijah or the resurrected John the Baptist . So far, however, no apocryphal text has been found in which Ezra was equated with Enoch in a similarly explicit way.

At least the main part of the Ethiopian Book of Enoch was around the year 0 CE. Z. has been written. The 4th book Esra followed a few decades later in the last third of the first century a. Z. Both writings came from Palestinian Jews. In Palestine, at the time of the second temple of YHWH, the Sadducees group played a decisive role. The group was formed around 150 BCE mainly from members of the Jerusalem upper class and occupied the most important and significant posts of the temple staff. “Their economic and social livelihoods were closely linked to the temple and the Torah as the constitution of the temple state.” This livelihood was deprived of them when Roman legionaries under the orders of General Titus destroyed the temple. This happened in 70 u. Z. in the first year of the reign of Emperor Vespasian . The story goes back to Ibn Hazm that a group of such Sadducees emigrated to Yemen and that it was precisely this group that saw the Son of God in Ezra. The historian Haim Ze'ev Hirschberg found this story credible. Apart from that, no historical or archaeological evidence for the real existence of a Jewish Ezra belief has yet been discovered.

literature

- Wolfgang J. Müller, Else Förster: Esra . In: Real Lexicon on German Art History . Volume 6, 1968, Col. 25-40

Web links

- Thomas Hieke : Esra. In: Michaela Bauks, Klaus Koenen, Stefan Alkier (eds.): The scientific biblical dictionary on the Internet (WiBiLex), Stuttgart 2006 ff., Accessed on September 4, 2008.

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d John Walker: Who Is' Uzair? In: The Moslem World , Volume 19, 1929, doi : 10.1111 / j.1478-1913.1929.tb02411.x , p. 303.

- ↑ a b c d e Bernhard Heller: 'Uzair . In: Martin Theodor Houtsma, Thomas Walker Arnold, Arent Jan Wensinck, Wilhelm Heffening, Hamilton Alexander Rosskeen Gibb, Évariste Lévi-Provençal (eds.): Enzyklopaedie des Islam · Volume IV . Verlag Otto Harrassowitz, Leipzig 1934, p. 1150.

- ↑ Bernhard Heller: 'Uzair . In: Martin Theodor Houtsma, Thomas Walker Arnold, Arent Jan Wensinck, Wilhelm Heffening, Hamilton Alexander Rosskeen Gibb, Évariste Lévi-Provençal (eds.): Enzyklopaedie des Islam · Volume IV . Verlag Otto Harrassowitz, Leipzig 1934, p. 1150. After Paul Casanova: Idris et Ouzair . In: Journal asiatique . Volume 205, 1924, pp. 356-360.

- ↑ Abdulla Galadari: Qur'anic Hermeneutics . Bloomsbury Academic, London / New York / Oxford / New Delhi / Sydney 2018, ISBN 978-1-350-07004-2 , p. 85.

- ↑ The Koran • Arabic-German • Translation and scientific commentary • Volume 7. Gütersloher Verlagshaus, Gütersloh 1996, ISBN 3-579-00342-9 , p. 316.

- ↑ Abdullāh as-Sāmit Frank Bubenheim, Nadeem Elyas: The noble Quran and the translation of its meanings into the German language . König-Fahd-Complex for printing the Koran, Medina, 2003 ( PDF file ).

- ↑ Muḥammad ibn Ismāʿīl al-Buchārī: al-Jāmiʿ as-sahīh . Book 97, Chapter 24, Hadith No. 65 (7439) (excerpt) ( Link ).

- ^ The Quranic Arabic Corpus - Word by Word Grammar, Syntax and Morphology of the Holy Quran. Retrieved May 2, 2019 .

- ^ The Quranic Arabic Corpus - Quran Dictionary. Retrieved May 2, 2019 .

- ^ The Quranic Arabic Corpus - Word by Word Grammar, Syntax and Morphology of the Holy Quran. Retrieved May 2, 2019 .

- ↑ Peter Schäfer: Two gods in heaven . Verlag CH Beck, Munich 2017, ISBN 978-3-406-70412-3 , pp. 17-19.

- ↑ Peter Schäfer: Two gods in heaven . Verlag CH Beck, Munich 2017, ISBN 978-3-406-70412-3 , pp. 18-19, 20, 75, 95, 154.

- ↑ Peter Schäfer: Two gods in heaven . Verlag CH Beck, Munich 2017, ISBN 978-3-406-70412-3 , S. 151st

- ↑ Peter Schäfer: Two gods in heaven . Verlag CH Beck, Munich 2017, ISBN 978-3-406-70412-3 , pp. 151–152.

- ↑ a b c d e Abdulla Galadari: Qur'anic Hermeneutics . Bloomsbury Academic, London / New York / Oxford / New Delhi / Sydney 2018, ISBN 978-1-350-07004-2 , p. 87.

- ↑ Peter Schäfer: Two gods in heaven . Verlag CH Beck, Munich 2017, ISBN 978-3-406-70412-3 , pp. 23-71.

- ↑ Peter Schäfer: Two gods in heaven . Verlag CH Beck, Munich 2017, ISBN 978-3-406-70412-3 , pp. 11, 17, 154, 155.

- ↑ Mark Lidzbarski: De propheticis, quae dicuntur, legendis Arabicus. Verlag Guilelmi Drugulini, Leipzig 1893, p. 35.

- ↑ Bernhard Heller: 'Uzair . In: Martin Theodor Houtsma, Thomas Walker Arnold, Arent Jan Wensinck, Wilhelm Heffening, Hamilton Alexander Rosskeen Gibb, Évariste Lévi-Provençal (eds.): Enzyklopaedie des Islam · Volume IV . Verlag Otto Harrassowitz, Leipzig 1934, p. 1151.

- ↑ 4th Book of Ezra : Chapter 14, Verses 18 to 48 ( Link ).

- ↑ Talmud Bavli : Seder Nezikin, Masechet Sanhedrin. Perek 2, Daf 21b [Babylonian Talmud: Order of Damages, Treatise High Council. Section 2, panel 21 b] ( Link ).

- ↑ 4th Book of Ezra : Chapter 14, Verses 49 to 50 ( Link ).

- ^ Hermann Gunkel: The 4th book Esra . In: Emil Kautzsch (ed.): The Apocrypha and Pseudoepigraphies of the Old Testament • Second volume . Verlag JCB Mohr, Tübingen 1921, p. 401, note n.

- ↑ 1st Book of Moses : Chapter 5, verse 24 ( Link ).

- ↑ Peter Schäfer: Two gods in heaven . Verlag CH Beck, Munich 2017, ISBN 978-3-406-70412-3 , p. 110.

- ↑ 1st Book of Enoch : Chapter 12, Verse 3 and Chapter 15, Verse 1 and Chapter 92, Verse 1 ( Link ).

- ↑ Peter Schäfer: Two gods in heaven . Verlag CH Beck, Munich 2017, ISBN 978-3-406-70412-3 , pp. 56-59.

- ↑ Gospel according to Mark : chapter 6, verses 14 to 15 and chapter 8, verses 27 to 28 ( link and link ).

- ^ Karl Kertelge: Gospel of Mark . Echter Verlag, Würzburg 1994. pp. 64-65, 84-85.

- ↑ Peter Schäfer: Two gods in heaven . Verlag CH Beck, Munich 2017, ISBN 978-3-406-70412-3 , p. 52.

- ↑ Peter Schäfer: Two gods in heaven . Verlag CH Beck, Munich 2017, ISBN 978-3-406-70412-3 , p. 61.

- ↑ Peter Schäfer: Two gods in heaven . Verlag CH Beck, Munich 2017, ISBN 978-3-406-70412-3 , p. 24.

- ↑ Kurt Schubert: Jewish history . Verlag CH Beck, Munich 2002, ISBN 3-406-44918-2 , p. 12.

- ^ A b Wolfgang Oswald, Michael Tilly: History of Israel . Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 2016, ISBN 978-3-534-26805-4 , p. 129.

- ↑ Kurt Schubert: Jewish history . Verlag CH Beck, Munich 2002, ISBN 3-406-44918-2 , p. 13.

- ^ Wolfgang Oswald, Michael Tilly: History of Israel . Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 2016, ISBN 978-3-534-26805-4 , p. 149.

- ^ Haim Zeev Hirschberg: In Islam . In: Fred Skolnik, Michael Berenbaum (eds.): Encyclopaedia Judaica • Volume 6. Thomson Gale Publishing, Detroit / New York / San Francisco / New Haven / Waterville / London 2007, ISBN 978-0-02-865934-3 , p 653. According to Haim Zeev Hirschberg: Yisrāʾēl ba-ʿArāv [Israel in Arabia] . Mossad Bialek Publishing House, Tel Aviv, 1946.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Esra |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Priest and descendant of the first high priest Aaron |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 6th century BC BC or 5th century BC Chr. |

| DATE OF DEATH | 5th century BC BC or 4th century BC Chr. |