Vertebral Heart Score

The Vertebral Heart Score ( English for ' vortex - heart value', abbreviation VHS ) - also Vertebral Heart Size (English for 'vortex heart size'), Vertebral Heart Scale (English for 'vortex heart scale') ) or cardiac vertebral sum - is a measured variable obtained from an x-ray of the chest in animals, which allows an assessment of the heart size regardless of the patient's size, similar to the heart-thorax quotient in human medicine. The VHS is primarily determined in domestic dogs and is used to detect an enlarged heart , especially in the case of heart diseases associated with heart enlargement ( dilated cardiomyopathies ). With the method, the longitudinal and transverse axes of the heart are transferred to the thoracic spine from the fourth thoracic vertebra and the number of vertebrae that occupy these segments is determined. The VHS was established in 1995 by Buchanan and Bucheler. A VHS <10.5 indicates a normal heart size in dogs, for some breeds even higher values can be considered healthy.

Determination and standard values

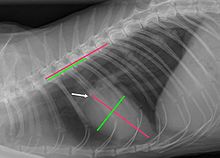

The VHS is usually determined using a chest x-ray in the lateral position. The X-ray image shows the distance from the branching of the windpipe to the apex of the heart as well as a right-angled distance at the widest part of the heart. For dogs with a large enlargement of the left atrium, Buchanan suggests placing the upper end of the longitudinal axis on the raised left bronchus. In older cats, in which the long heart axis often runs almost parallel to the sternum , the base of the vein of the anterior lung lobe is recommended as the measuring point instead of the trachea. The heart axes can also be measured on an X-ray in the supine position. However, in this projection the left atrium is not involved in the formation of the heart silhouette in the dog.

The two stretches are transferred to the thoracic spine , each beginning at the front end of the fourth thoracic vertebra . The number of vertebrae occupying these stretches is then determined. If the end of the segment no longer includes a whole vertebra, this partial vertebra is determined with an accuracy of one tenth: For example, if the length of the longitudinal axis extends from the beginning of the fourth to the middle of the ninth thoracic vertebra, the value for this segment is 5.5. The length of a vertebral body together with the associated intervertebral disc serves as a relative length measure that reflects the size of the individual. Since vertebral body lengths vary within the spine, it is important to always start with a defined vertebra. The heart-thorax quotient used in human medicine to assess the size of the heart is unsuitable for dogs because of the great differences in the breed of the chest.

The Vertebral Heart Score is the sum of the vertebrae that occupy the longitudinal and transverse axes. A VHS up to 10.5 (dog) or 8.1 (cat) is considered normal, higher values indicate an enlarged heart (cardiomegaly). The VHS is not used to detect a reduction in the size of the heart ( microcardia ). For this purpose, the number of intercostal spaces is determined over which the heart silhouette extends. A heart reduction is usually not caused by a heart disease, but by a lack of blood volume . The heart takes up less than two intercostal spaces.

There are some breeds of dogs that are typical of even larger VHS. For the German boxer, a normal range of 10.8 to 12.4 applies, for French and English bulldogs from 11 to 14.4 and for the Boston Terrier from 10.3 to 13.1. For other breeds ( Miniature Spitz , Cavalier King Charles Spaniel , Pug , Whippet and Labrador Retriever ) values up to 11.5 can be considered physiological.

The relationship between the size of the heart and thoracic vertebrae has now also been investigated in other animal species. Onuma et al. determined a mean VHS of 7.55 in domestic rabbits with a body mass of less than 1.6 kg, and 8 in heavier animals. The same working group presented the heart axes in ferrets in relation to the length of the sixth thoracic vertebrae (Th6). In females this was Longitudinal axis of the heart 3 to 3.3 times, the transverse axis 2.2 to 2.4 times the Th6 length, for male animals 3.2 to 3.7 times or 2.3 to 2.7 times. For alpaca -Lämmer an average of 9.36 VHS has been found for the Katta 8.9.

In humans, the heart-thorax quotient ( cardiothoracic ratio , CT quotient) is determined to assess the size of the heart . The distances from the center line to the extreme right and left edge of the heart are determined using a standing image from the front, and the sum of both distances is related to the transverse diameter of the chest at the level of the right diaphragmatic dome . The ratio should not exceed 1: 2.

Influencing factors and sources of error

The definition of the end points of the route and thus the determination of the length of the heart axes and the VHS are subject to subjective assessments. In one study, the VHS fluctuated by up to one vertebra length, depending on the examiner. However, if the measurements are carried out by experienced veterinarians, the coefficient of variation is only 2.8% and the values obtained correlate well with the findings of other examination methods of the heart ( cardiac ultrasound examination , EKG ). Age has no influence on the VHS in dogs, while healthy young cats have a slightly higher VHS and the values typical for adult cats only appear at the age of nine months. Gender and chest shape do not affect the VHS. The exposure should always be taken with maximum inhalation, since in the exhalation phase the heart size fluctuates more between systole and diastole .

Above all, accumulations of fluid or fat deposits in the pericardium can lead to an overestimation of the size of the heart, as the radiographically detectable heart silhouette actually represents the pericardium, which is normally close to the heart. Fluid accumulation in the pericardium lead to a VHS greater than 12. For substances occurring mainly at Boston Terrier, Bulldog and Pug half and wedge vertebrae in the thoracic spine, the vertebral body length is reduced, which is at least partially responsible for the higher VHS values in these breeds . Vertebrae that are grown together ( block vortices ) also falsify the VHS. Whether the VHS is also page dependent is assessed differently in the literature. In some studies, the VHS was slightly larger for recordings in the right lateral position than in those in the left lateral position, presumably because the distance between the heart and the X-ray film is slightly larger, which leads to a slightly enlarged image. The same side should therefore always be selected for follow-up examinations.

Expressiveness

In dogs in particular, the variability in heart size is relatively high. The specificity (correct negative rate) of the procedure is given as 76% for dogs, the sensitivity (correct positive rate) as 80%. In cats, the specificity of the VHS is acceptable, but its sensitivity for recognizing heart diseases is only low. This is mainly due to the fact that cats mainly suffer from diseases with a thickening of the heart wall ( hypertrophic cardiomyopathies ). However, the narrowing of the interior of the heart chambers caused by the concentric thickening of the heart chamber wall does not have to be reflected in an enlargement of the outer silhouette.

With the severity of a heart disease, the reliability of the VHS increases in both dogs and cats. Advantages of the radiological heart examination are that an X-ray device is available in many veterinary practices and changes in the shape of the heart silhouette as a result of enlargement of individual heart sections as well as heart-related lung changes ( pulmonary edema , congestion of the pulmonary vessels) can be seen on the X-ray image . The determination of the VHS is therefore a useful contribution to heart diagnosis. For most heart diseases in dogs and cats, however, the cardiac ultrasound examination is the more sensitive examination technique; for cardiac arrhythmias and early forms of dilated cardiomyopathy, the EKG examination, especially the long-term EKG . The combination of cardiac ultrasound and long-term ECG is the " gold standard " for dilated cardiomyopathies , so no statement can be made as to whether this may also deliver false positive or false negative results.

literature

- Michael Deinert: Therapy of acquired heart diseases in dogs and cats . Enke, Stuttgart 2010, ISBN 978-3-8304-1148-2 , pp. 22-24 .

- WH Adams and Silke Hecht: Heart and large vessels . In: Silke Hecht (Ed.): X-ray diagnostics in the small animal practice . 2nd Edition. Schattauer, Hannover 2012, ISBN 978-3-7945-2812-7 , p. 181-203 .

Web links

- Markus Killich and Gerhard Wess: X-ray diagnostics: determining the size of the heart , Ludwig Maximilians University, Munich

- James Buchanan Cardiology Library: Vertebral Heart Size (VHS)

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c J. W. Buchanan and J. Bucheler: Vertebral scale system to measure canine heart size in radiographs . In: J Am Vet Med Assoc . tape 206 , no. 2 , 1995, p. 194-199 , PMID 7751220 .

- ↑ a b W. H. Adams and Silke Hecht: Heart and large vessels . In: Silke Hecht (Ed.): X-ray diagnostics in the small animal practice . 2nd Edition. Schattauer, Hannover 2012, ISBN 978-3-7945-2812-7 , p. 185 .

- ↑ James Buchanan Cardiology Library: Vertebral Heart Size (VHS)

- ↑ a b Antje Hartmann: Guide to the interpretation of the heart silhouette on the X-ray image in small animals. In: Kleintierpraxis Volume 63, Issue 7 2018, pp. 404-428.

- ↑ Markus Killich and Gerhard Wess: X-ray diagnostics: determining the size of the heart , LMU Munich

- ↑ WH Adams and Silke Hecht: Heart and large vessels . In: Silke Hecht (Ed.): X-ray diagnostics in the small animal practice . 2nd Edition. Schattauer, Hannover 2012, ISBN 978-3-7945-2812-7 , p. 191 .

- ↑ a b C. R. Lamb et al .: Use of breed-specific ranges for the vertebral heart scale as an aid to the radiographic diagnosis of cardiac disease in dogs. In: The Veterinary Record. Volume 148, Number 23, June 2001, pp. 707-711, PMID 11430680 .

- ↑ a b c d K. Jepsen-Grant, RE Pollard and LR Johnson: Vertebral heart scores in eight dog breeds. In: Veterinary radiology & ultrasound. Volume 54, number 1, January-February 2013, pp. 3–8, doi: 10.1111 / j.1740-8261.2012.01976.x , PMID 22994206 .

- ↑ V. Bavegems et al .: Vertebral heart size ranges specific for whippets. In: Veterinary radiology & ultrasound. Volume 46, Number 5, September-October 2005, pp. 400-403, PMID 16250398 .

- ↑ a b D. Bodh et al .: Vertebral scale system to measure heart size in thoracic radiographs of Indian Spitz, Labrador retriever and Mongrel dogs. In: Veterinary world. Volume 9, Number 4, April 2016, pp. 371–376, doi: 10.14202 / vetworld.2016.371-376 , PMID 27182132 , PMC 4864478 (free full text)

- ↑ M. Onuma et al .: Radiographic measurement of cardiac size in 27 rabbits. In: The Journal of veterinary medical science. Volume 72, Number 4, April 2010, pp. 529-531, PMID 20035120 .

- ↑ M. Onuma et al .: Radiographic measurement of cardiac size in 64 ferrets. In: The Journal of veterinary medical science. Volume 71, Number 3, March 2009, pp. 355-358, PMID 19346707 .

- ^ NC Nelson, JS Mattoon and DE Anderson: Radiographic appearance of the thorax of clinically normal alpaca crias. In: American journal of veterinary research. Volume 72, number 11, November 2011, pp. 1439-1448, doi : 10.2460 / ajvr.72.11.1439 , PMID 22023121 .

- ↑ M. Makungu et al .: Radiographic thoracic anatomy of the ring-tailed lemur (Lemur catta). In: Journal of medical primatology. Volume 43, Number 3, June 2014, pp. 144–152, doi : 10.1111 / jmp.12102 , PMID 24444331 .

- ↑ M. Thelen: Radiological determination of the heart size . In: M. Thelen et al. (Ed.): Imaging cardio diagnostics . 1st edition. Georg Thieme, Stuttgart 2010, ISBN 978-3-13-135871-4 .

- ↑ K. Hansson et al .: Interobserver variability of vertebral heart size measurements in dogs with normal and enlarged hearts. In: Veterinary radiology & ultrasound. Volume 46, Number 2, March-April 2005, pp. 122-130, PMID 15869155 .

- ↑ a b c H. Nakayama, T. Nakayama and RL Hamlin: Correlation of cardiac enlargement as assessed by vertebral heart size and echocardiographic and electrocardiographic findings in dogs with evolving cardiomegaly due to rapid ventricular pacing. In: Journal of veterinary internal medicine. Volume 15, Number 3, May-June 2001, pp. 217-221, PMID 11380030 .

- ↑ MM Sleeper and JW Buchanan: Vertebral scale system to measure heart size in growing puppies. In: Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. Volume 219, Number 1, July 2001, pp. 57-59, PMID 11439770 .

- ↑ L. Gaschen et al .: Cardiomyopathy in dystrophin-deficient hypertrophic feline muscular dystrophy. In: Journal of veterinary internal medicine. Volume 13, Number 4, July-August 1999, pp. 346-356, PMID 10449227 .

- ↑ WH Adams and Silke Hecht: Heart and large vessels . In: Silke Hecht (Ed.): X-ray diagnostics in the small animal practice . 2nd Edition. Schattauer, Hannover 2012, ISBN 978-3-7945-2812-7 , p. 191 .

- ↑ C. Guglielmini et al .: Accuracy of radiographic vertebral heart score and sphericity index in the detection of pericardial effusion in dogs. In: Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. Volume 241, Number 8, October 2012, pp. 1048-1055, doi: 10.2460 / javma.241.8.1048 , PMID 23039979 .

- ↑ a b Michael Deinert: Therapy of acquired heart diseases in dogs and cats . Enke, Stuttgart 2010, ISBN 978-3-8304-1148-2 , pp. 23 .

- ↑ C. Guglielmini et al .: Diagnostic accuracy of the vertebral heart score and other radiographic indices in the detection of cardiac enlargement in cats with different cardiac disorders. In: Journal of feline medicine and surgery. Volume 16, number 10, October 2014, pp. 812-825, doi: 10.1177 / 1098612X14522048 , PMID 24518255 .

- ^ C. Guglielmini and A. Diana: Thoracic radiography in the cat: Identification of cardiomegaly and congestive heart failure. In: Journal of veterinary cardiology. Volume 17 Suppl 1, December 2015, pp. S87-101, doi: 10.1016 / j.jvc.2015.03.005 , PMID 26776597 (review).

- ↑ Nuala Summerfield: Diagnosing Preclinical DCM: A Practical Approach . In: kleintier.konkret . tape 18 , no. 5 , 2015, p. 40-42 , doi : 10.1055 / s-0035-1558510 .

- ↑ MM Sleeper, R. Roland and KJ Drobatz: Use of the vertebral heart scale for differentiation of cardiac and noncardiac causes of respiratory distress in cats: 67 cases (2002-2003). In: Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. Volume 242, number 3, February 2013, pp. 366-371, doi: 10.2460 / javma.242.3.366 , PMID 23327180 .

- ↑ Michael Deinert: Therapy of acquired heart diseases in dogs and cats . Enke, Stuttgart 2010, ISBN 978-3-8304-1148-2 , pp. 24 .

- ^ G. Wess et al .: Prevalence of dilated cardiomyopathy in Doberman Pinschers in various age groups. In: Journal of veterinary internal medicine. Volume 24, number 3, May-June 2010, pp. 533-538, doi : 10.1111 / j.1939-1676.2010.0479.x , PMID 20202106 .

- ^ G. Wess et al .: Cardiac troponin I in Doberman Pinschers with cardiomyopathy. In: Journal of veterinary internal medicine. Volume 24, Number 4, 2010 Jul-Aug, pp. 843-849, doi : 10.1111 / j.1939-1676.2010.0516.x , PMID 20412436 .