Xenokeryx

| Xenokeryx | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

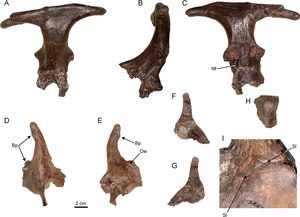

Xenokeryx , remains of the horn; A – C: occipital horns in anterior, lateral and posterior view (holotype); D – G: forehead weapons of different individuals; H: cross section of the forehead weapon; I: Detail of the forehead weapon |

||||||||||||

| Temporal occurrence | ||||||||||||

| Aragonium (Middle Miocene ) | ||||||||||||

| 15.9 to 15.4 million years | ||||||||||||

| Locations | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||||

| Xenokeryx | ||||||||||||

| Sánchez , Cantalapiedra , Ríos , Quiralte & Morales , 2015 | ||||||||||||

Xenokeryx is an extinct species from the group of cloven-hoofed animals . It is known for a few dozen fossil remains that were discovered in the fossil depositof La Retama in central Spain . The age of the finds is 15.9 to 15.4 million years, which means that theybelongto the beginning of the Middle Miocene . Overall, Xenokeryx represented a deer-like animalin appearance, which is characterized by a conspicuous horn. This consists of three bone formations, a front pair of conical frontpegs above the eyes and a rear T-shaped appendage that attached to the back of the head. Because of this conspicuous horn, the genus is placed in the also extinct family of the Palaeomerycidae and referred to the group of forehead weapon bearers. The family was originally thought to be more closely related to the deer, but recent research suggests a closer relationship to the giraffe-like . The animals lived in a warm, dry landscape near the water. The first scientific description took place in 2015.

features

Xenokeryx has been identified over around four dozen individual bone fragments that were not found in the skeletal structure. These consist of both mandibular and maxillary fragments and parts of the skull with attached horns as well as elements of the musculoskeletal system and belong to several individuals. Only a few parts of the skull have survived. From today's point of view, the horns had an unusual shape and consisted of two front cone-like appendages that rose in pairs above the eye windows on the frontal bone , while a third appendage began further back on the occiput . The front horns protruded vertically and showed a slight curvature inwards and backwards in the upper part. The length of the largest cone was about 9.3 cm measured over the curve, the clear height was 6.3 cm, the diameter at the base 3.9 cm with a circumference of 11 cm. At the back of the base was a wing-like extension with a pair of smaller humps on it. At the base the cones had an approximately triangular cross-section, towards the top they became increasingly oval. The tip ended round and was folded, making it resemble the horned cones of the giraffe-like . The top was also surrounded by individual bumps. In contact with the frontal bone, the inside of the cones consisted of air-filled chambers, the outside wall of the cones themselves was formed from dense bone substance. The rear "horn" appeared as a massive, erect, slightly forwardly inclined cone, which was a total of 10.7 cm high and 6.1 cm wide at the base. At the upper end, laterally horizontally directed extensions began, so that the entire structure was given a T-shape. The horizontal appendages had tips curved slightly downwards. The back of the ascending cone was largely smooth, but with fine ripples. The occiput attached to the rear horn had an extremely long, upwardly drawn shape due to the horn attachment. As a result, the planum nuchale, the upper section of the occiput, was also strongly stretched and thus enlarged the attachment point of the neck muscles.

The lower and upper jaws are only incompletely documented, as is the dentition, of which only the molars have been preserved. As with today's forehead weapon carriers, these consist of three premolars and three molars per jaw arch. The rear molars had low ( brachyodontic ) tooth crowns with a buno-selenodontic occlusal surface pattern, that is, there were characteristic, paired cusps that were connected by crescent-shaped enamel strips running along the longitudinal axis of the teeth . The humps rose on a broad, rounded base; In the upper jaw they stood on the cheek side, in the lower jaw on the tongue side one above the other. The enamel ridges showed slight folds, a characteristic Palaeomeryx fold was formed on the rear molars of the lower jaw, a short enamel fold on the lip side typical of numerous forehead weapon wearers. However, it was only weakly formed and disappeared again with greater wear of the teeth. The upper posterior molar reached a length of 3.7 cm, the entire upper molar row measured up to 10.9 cm.

The postcranial skeleton is also only very fragmented, only a few carpal and tarsal bones as well as individual phalanges of toes are complete. Statements can therefore only be made to a limited extent. The ulna and radius were fused together at the lower end, which is not known from the related Triceromeryx . The femur had a clearly raised head, which was elongated to the side and sat on a pronounced neck. It also had a noticeable femoral head pit. Typically for the ungulates , the main axis of the lower limb sections ran through the third and fourth rays of the hands and feet, the corresponding metacarpal and metatarsal bones (rays III and IV) were fused together. At the foot, however, there were still reduced side rays (II and V), which in the upper section were clearly connected to the cannon leg. The anklebone roll, the proximal joint end of the ankle bone was asymmetrically built with a larger and wider outer joint part in comparison to the inner. The entire bone measured 4.7 cm in length. With a length of up to 5.1 cm, the first phalanx clearly exceeded the second. This was 3.3 cm long and was built clearly robust.

Reference

The only known finds of Xenokeryx so far came to light in La Retama in the Spanish province of Cuenca . The fossil deposit was discovered in 1989 and belongs to one of several sites rich in finds in the Loranca Basin west of Loranca del Campo . The Loranca Basin is a narrow, north-south oriented marginal depression and is mainly filled with Cenozoic deposits. The found layers of La Retama consist of marls and clays that are interspersed with carbonate concretions and numerous organic material such as plant remains . They go back to a former river delta . The finds show hardly any evidence of relocation. In addition to molluscs, it is mainly composed of vertebrates and includes remains of fish, turtles, crocodiles and mammals. Anchitherium , an early representative of the Equidae , dominates among the large mammals , and Hispanotherium , a member of the rhinos , is another odd- toed ungulate . In addition, especially artifacts such as pigs , deer or the extinct Cainotheriidae have been identified, as well as proboscis and various predators . The small mammals are comparatively poor in species, the relative diversity of bats compared to rodents and insectivores is remarkable . The most common small mammal , however, is Heteroxerus , a ground-living squirrel . Due to the presence of megacricetodon from the group of long-tailed mice , La Retama can be placed at the beginning of the Middle Miocene , more precisely in the Aragonium . The absolute age of the finds is 15.9 to 15.4 million years. The composition of the fauna speaks for a predominance of open landscapes with bush vegetation under warm climatic influence.

Systematics

|

Internal system of forehead weapon carriers according to Sánchez et al. 2015

|

Xenokeryx is a genus from the extinct family of Palaeomerycidae within the order of the cloven-hoofed animals (Artiodactyla). The Palaeomerycidae were widespread throughout the northern hemisphere during the Miocene and are deer-like animals in habit , but with comparatively shorter and stronger legs, which suggests less well-developed, persistent walking characteristics. Noteworthy are the unusually designed head weapons, which were probably mostly male animals. These had no resemblance to the antlers of the deer (Cervidae), which are completely renewed annually. They also differed from the horns of the pronghorn (Antilocapridae), in which only the horn cover is exchanged in the annual cycle, there are also differences to the horns of the horn-bearers (Bovidae), which have lifelong horn sheaths and are never forked or branched. Possibly the horns of the Palaeomerycidae were overgrown with skin, comparable to the frontal cusps of the giraffe-like (Giraffidae). As a rule, the head arms of the Palaeomerycidae consisted of a pair of conical bony outgrowths that protruded above the eyes, in addition, a third, partly forked horn was formed on the occiput. Due to the formation of the Gehörns Palaeomerycidae can clearly in the group of the forehead support arms to be incorporated (Pecora) which phylogenetically advanced forms of the cloven-hoofed animals such as giraffes-like, musk deer include (Moschidae), deer or Bovidae. The exact systematic position of the Palaeomerycidae is scientifically controversial. Often they are closely related to the deer and are grouped with them under the superfamily Cervoidea . Other authors, however, see a closer relationship with the giraffe-like. More recent studies advocate the latter constellation and classify the Palaeomerycidae in the superordinate taxon Giraffomorpha . In addition to the developed conical anterior horns and some special skull features such as the shape of the retroarticular process of the temporal bone and its contact with the external auditory canal , the design of the scaphoid and cubic bone of the foot are indications of a close relationship with the giraffe-like . Both bones are typically fused together in developed ungulates. On the lower surface there is a noticeable bar, which is also found in today's giraffe-like and their extinct relatives. The lack of small grooves above the lower articular surface of the metatarsal bones, which are formed in numerous ungulates and whose presence is possibly associated with a significantly faster mode of locomotion, can be seen as a further indication of this relationship .

|

Internal systematics of the Palaeomerycidae according to Sánchez et al. 2015

|

The Palaeomerycidae were originally divided into several subfamilies, of which the actual Palaeomerycinae were distributed in Eurasia, the Dromomerycinae and Craniomerycinae in North America. The last two groups are now placed as the family of the Dromomerycidae in the vicinity of the deer and differ from the Palaeomerycidae by the structure of the front and rear horns. The rear horn is also not pronounced in all representatives of the North American forms and caused less dramatic changes to the occiput due to the fact that it was mostly rod-shaped. Currently, only the Eurasian genera are considered to belong to the Palaeomerycidae family, as some exclusively African forms that were once counted among these are still more closely associated with the giraffe-like ( Giraffoidea ) today . Phylogenetic studies of the Eurasian Palaeomerycidae reveal two separate clades . One, the so-called Ampelomeryx clade, contains representatives with flattened, non-pneumatized front horns and a generally board-like, flat, two-part rear horn that rose steeply and ended more or less rounded. The Triceromeryx clade, to which Xenokeryx can also be assigned, is characterized by its front horns with rounded cross-sections and filled with air chambers and a rear, T- or Y-shaped horn with a variety of designs. Other differences are found in the Zahnbau which during Ampelomeryx example, a well developed -Klade Palaeomeryx includes -Falte on the lower molars, which in turn in the Triceromeryx is but slightly marked -Klade or missing.

The genus Xenokeryx was scientifically described by Israel M. Sánchez and fellow researchers in 2015 . The foundations from La Retama in Spain formed the basis for this. A complete T-shaped horn cone of the occiput serves as the holotype (specimen number MNCN -74448). All found material is kept in Barcelona. The generic name Xenokeryx is derived from the Greek language , where ξένος ( xenos ) stands for “strange” or “unfamiliar”, while κήρυξ ( keryx = “herald”) refers to κέρας ( keras ) for “horn”; the scientific name thus reflects the unusual shape of the occipital horn of the arthropod. The only known species is Xenokeryx amidalae . The species epithet refers to the character Padme Amidala from the Star Wars universe , who in the movie Star Wars: Episode I - The Phantom Menace has a hairstyle reminiscent of the shape of the back horn of Xenokeryx wore.

literature

- Israel M. Sánchez, Juan L. Cantalapiedra, María Ríos, Victoria Quiralte and Jorge Morales: Systematics and Evolution of the Miocene Three-Horned Palaeomerycid Ruminants (Mammalia, Cetartiodactyla). PlosOne 10 (12), 2015, p. E0143034 doi: 10.1371 / journal.pone.0143034

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i Israel M. Sánchez, Juan L. Cantalapiedra, María Ríos, Victoria Quiralte and Jorge Morales: Systematics and Evolution of the Miocene Three-Horned Palaeomerycid Ruminants (Mammalia, Cetartiodactyla). PlosOne 10 (12), 2015, p. E0143034

- ^ Israel M. Sánchez, MJ Salesa and Jorge Morales: Revisión sistemática del género Anchitherium Meyer 1834 (Equidae; Perissodactyla) en España. Estudios Geológicoa 54, 1998, pp. 39-63

- ↑ Esperanza Cerdeño: New remains of the rhinocerotid Hispanotherium matritense at La Retama site: Tagus basin, Cuenca, Spain. Geobios 25 (5), 1992, pp. 671-679

- ↑ MA Álvarez Sierra, I. García Paredes, L. van den Hoek Ostend, AJ van der Meulen, P. Peláez-Campomanes and P. Sevilla: The Middle Aragonian (Middle Miocene) Micromammals from La Retama (Intermediate Depression, Tagus Basin) Province of Cuenca, Spain. Estudios Geológicos 62 (1), 2006, pp. 401-428

- ^ Adriana Oliver and Pablo Peláez-Campomanes: Megacricetodon vandermeuleni, sp. nov. (Rodentia, Mammalia), from the Spanish Miocene: a New Evolutionary Framework for Megacricetodon. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 33 (4), 2013, pp. 943-955

- ↑ Jorge Morales, Manuel Nieto, Pablo Peláez-Campomanes, Dolores Soria, Marian Alvarez, Luis Alcalá, Lara Amezua, Bearriz Azanza, Esperanza Cerdeño, Remmerr Daams, Susana Fraile, Jordi Guillem, Manuel Hoyos, Laureano Merino, Isabel de Miguel, Roser Monparler, Plinio Monroya, Benigno Pérez, Manuel Salesa and Israel Sánchez: Vertebrados continentales del Terciario de la Cuenca de Loranca (Provincia de Cuenca). In: E. Aguirre and I. Rábano (eds.): La Huella del Pasado: Fósiles de Castilla-La Mancha. Toledo, Junta de Comunidades de Castilla-La Mancha, 1999, pp. 235-260

- ^ A b Donald R. Prothero and Matthew R. Liter: Family Palaeomerycidae. In: Donald R. Prothero and Scott E. Foss (Eds.): The Evolution of Artiodactyls. Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, 2007, pp. 241-248

- ^ Alan W. Gentry, Gertrud E. Rössner and Elmar PJ Heizmann: Suborden Ruminantia. In: Gertrud E. Rössner and Kurt Heissig (Eds.): The Miocene Land Mammals of Europe. Munich: Verlag Dr. Friedrich Pfeil, 1999, pp. 225-253

- ^ Gertrud E. Rössner: Systematics and palaeoecology of Ruminantia (Artiodactyla, Mammalia) from the Miocene of Sandelzhausen (southern Germany, northern Alpine Foreland basin). Paläontologische Zeitschrift 84, 2010, pp. 123–162

- ↑ Qiu Zhanxiang, Yan Defa, Jia Hang and Sun Bo: Preliminary observations on newly found skeletons of Palaeomeryx from Shangwang, Shandong. Vertebrata PalAsiatica 23 (3), 1985, pp. 173-195