Customs union defeat

Zollvereinsniederlagen were branches of the German Customs Union in cities outside the customs area in the 19th century . Like free ports , they consisted of spatially delimited and customs-secured warehouse complexes that were rented to trading companies and used by them for the duty-free import, storage, further processing and refinement of goods imported from the customs union area. Such defeats occurred in particular in the Hanseatic cities of Bremen and Hamburg , which initially stayed away from the Zollverein for trade-policy considerations and served duty-free trade with the respective hinterland. After the Hanseatic cities joined the Zollverein in 1888, the defeats were dissolved and instead demarcated free port areas were designated for duty-free trade with foreign countries.

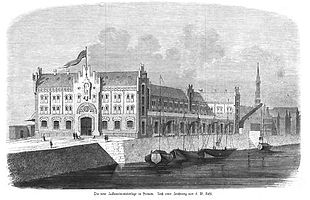

Bremen

In 1852, Bremen's mayor Arnold Duckwitz first considered setting up a customs union defeat. In 1854 Duckwitz and Johann Smidt negotiated with representatives of the Zollverein how goods from the Zollverein area should be treated. A main customs office in Bremen and customs offices in Bremerhaven and Vegesack were to be set up and the customs borders were to be changed to include an area around the Bremen- Sebaldsbrück train station . Another contract dated January 26, 1856 was signed by u. a. provided for further territorial regulations (to Hollerland , Borgfeld and Wümmedeich , left Ochtumufer ) and repealed the Weser tariffs . The Bremer Zollverein defeat in the free port at the Weserbahnhof and on the Tiefer was justified. The Weserbahnhof was rebuilt for this purpose by 1860. In Bremerhaven, the duty-free area was enlarged by 150 acres of land acquired by Prussia in 1866/67, and the Kaiserhafen could be built (1875/77). The defeats of the customs union existed until Bremen joined the German Customs Union in 1888. The reason for this was that Hanover and Oldenburg joined the German Customs Union in 1854 , which cut off Bremen from its hinterland.

Hamburg

In Hamburg the establishment of a Zollverein defeat became necessary after Holstein in 1864 and the Kingdom of Hanover in 1866 were integrated into the Prussian state and thus also into the Zollverein. Since Hamburg continued to insist on its free port status even after joining the North German Confederation in 1867 , the surrounding area was cut off for customs purposes. This led to an increased migration of manufacturing companies to the surrounding area, e.g. B. to Altona and Ottensen , which , according to a contemporary complaint, was converted from “a village with Klopstock's linden tree and a few thatched roofs into a handsome town with a large number of important shops and wholesale warehouses at Hamburg's expense and the fiscal income from these shops was ours Hometown were lost. "

After lengthy disputes about a suitable place, the extensive warehouse complex was built in 1869/70 along the Hamburg-Altona connecting railway in the immediate vicinity of the Sternschanze station. The architect was Hugo Stammann . The Zollverein defeat was operated by a stock corporation , two thirds of which were privately owned and one third owned by the Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg. The first chairman of the board of directors was the shipowner August Joseph Schön (1802–1870), who had particularly campaigned for the establishment of the defeat.

After the customs connection in 1888 and the simultaneous opening of the free port in the Speicherstadt , the defeat of the Zollverein passed completely into the ownership of the city. However, due to the loss of the special customs status, the industrial area soon lost its attractiveness, so that part of the storage area was transferred to various authorities, including the clothing office of the IX. Army Corps , was rented. After plans to convert the factory halls did not materialize, the buildings were gradually demolished to make room for the expansion of the neighboring slaughterhouse , the Sternschanze train station or, finally, for the construction of the Hamburg television tower .

literature

- Frank M. Hinz: Planning and financing of the Speicherstadt in Hamburg. Mixed economy company foundations in the 19th century with special consideration of the Hamburg Freihafen-Lagerhaus-Gesellschaft , LIT Verlag Münster 2000. ISBN 3-8258-3632-0 .

Individual evidence

- ^ Herbert Black Forest : History of the Free Hanseatic City of Bremen . Volume II, pp. 152, 232/233, 243, 292 and 329, Edition Temmen, Bremen 1995, ISBN 3-86108-283-7 .

- ^ Andreas Schulz: Guardianship and Protection: Elites and Citizens in Bremen 1750-1880 . Oldenbourg Verlag, 2002 ISBN 9783486565829 , p. 464. ( digitized version )

- ^ Legal Gazette of the Free Hanseatic City of Bremen . Schünemann Verlag, Bremen 1861, p. 1. ( digitized version )

- ^ Georg Fuhse: The economic history of Bremen until the 19th century . BoD - Books on Demand, 2017, ISBN 978-3-95507-511-8 ( google.de [accessed March 30, 2017]).

- ^ Michael Kotulla: German Constitutional Law 1806–1918: A collection of documents and introductions, Volume 4: Bremen . Springer-Verlag, 2015, ISBN 978-3-540-29505-1 , doi : 10.1007 / 978-3-540-29505-1 ( google.de [accessed on March 30, 2017]).

- ↑ Contemporary lawsuit cited above. according to Hinz, p. 46.

- ↑ Hinz, p. 55.

- ↑ Hinz, p. 49 ff.

- ↑ Hinz, p. 284 f.