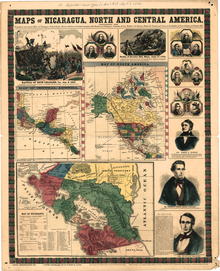

Second battle of Rivas

The Second Battle of Rivas took place on April 11, 1856 in Rivas / Nicaragua between the mercenary army of William Walker and Costa Rican troops. Although the Costa Ricans were able to force Walker's troops to withdraw with high losses of their own, they did not strategically exploit this tactical success due to the outbreak of cholera . Forced to retreat by the epidemic , the returning troops dragged cholera into Costa Rica, from which around 8% of the population died.

Strategic starting point

Rivas is located on the 30 km wide strip of land between the Pacific coast and Lake Nicaragua (Lago Cocibolca), the narrowest isthmus on the continent . The transit route of the Vanderbiltschen Transportgesellschaft Accessory Transit Company (ATC) ran across the isthmus between La Virgen on Lake Nicaragua and the Pacific port of San Juan del Sur . The ATC transported European and American emigrants from the eastern and central USA by sea to Greytown (San Juan del Norte), from where they traveled by paddle steamers over the Río San Juan and Lake Nicaragua to La Virgin. From there, the travelers crossed the isthmus by ox wagon (carreta) to San Juan del Sur, where they re-embarked and traveled on to California . This travel route was significantly shorter than the Panama route ( Aspinwall - Panama City railway line ) and considerably less complicated than an overland trip from the Mississippi to California. The transit route was vital for Walker's regime in Nicaragua, as new mercenaries as well as weapons and supplies of all kinds were transported mainly from New Orleans via Greytown to the Nicaraguan inland to Granada .

After the lost battle of Santa Rosa , Costa Rica on March 20, 1856, Walker's mercenaries had fled and also vacated the position in Rivas, where Walker's headquarters had been, in preparation for the invasion of Costa Rica. The advancing Costa Rican army crossed the border to Nicaragua at Peñas Blancas on April 5, 1856 and then split up into three columns:

- The main force under the Commander-in-Chief , President Juan Rafael Mora Porras , 1,800 men in strength with the aim of Rivas,

- a column of 300 men destined for La Virgin on Lake Nicaragua,

- a column of 300 men destined for San Juan del Sur on the Pacific coast.

While San Juan del Sur was occupied without resistance, there was a skirmish in La Virgin ; the pier for the paddle steamers of the transit company was burned down and some employees of the transit company were shot. Rivas was taken without a fight because Walker was already in Granada and reorganized his troops, while his Nicaraguan allies vacated Rivas as the Costa Ricans approached; however, some officers had defected to the Costa Rican side.

Walker planned from Granada on the coup-like regaining Rivas, as his forces the Costa Rican were seriously understaffed place.

The battle

Walker marched from Granada on April 9, 1856 with only 550 men, as the German and French companies had been disbanded due to the language difficulties of the mercenaries, which had led to the disaster of Santa Rosa, among other things, and only English-speaking mercenaries like Americans and Irish remained in Nicaraguan service. Walker's troop stayed at Ochomogo and the Rio Gíl Gonzáles and arrived on April 11 at around 8:00 a.m. on the outskirts of Rivas. According to Walker's information, the Costa Ricans owned an arsenal or powder magazine near the plaza. Apparently Mora had not expected an attack by the mercenaries, since no outposts or guards for the immediate external security of Rivas are mentioned in the entire literature .

To take the arsenal, Walker carried out a pincer attack from the north and south with the following columns:

- A column under Lieutenant Colonel Sanders with four rifle companies,

- a column under Major Brewster with three rifle companies,

- a column under Colonel Bruno von Natzmer of unknown strength,

- a column under Major O'Neal of unknown strength,

- a column of allied Nicaraguans under the leadership of the Cuban Colonel José María Machado.

Colonel Fry formed the reserve with at least two companies of light infantry. A small cavalry division under Captain Waters only fought dismounted.

Walker's surprise attack only succeeded in the early stages of the battle. Mora's troops organized themselves quickly and offered fierce resistance. Walker explicitly mentions some German and French snipers who took Major Brewster's riflemen under fire from a tower. The resistance of the far superior Costa Ricans demoralized the mercenaries, who had to expect that it would take days before the enemy could be driven from his entrenchments in the houses. When the Nicaraguan leader Colonel Machado fell, the morale of the Nicaraguans sank and they practically no longer took part in the further course of the battle.

By setting fire to some of the houses occupied by Walker's troops, the filibuster was forced to retreat at nightfall. The most seriously wounded were laid down in a church next to the altar , and the rest of the wounded were taken on mounts. Major Brewster and the rear guard covered the retreat, which was relatively silent. Walker's brother, Captain Norvell Walker, had slept through the filibusters' departure in a church tower. Since the completely exhausted Costa Ricans had not yet noticed the withdrawal of the mercenaries, he managed to break through to the withdrawing troops. The mercenaries and their Nicaraguan allies withdrew to Granada via Nandaime . The seriously wounded who were left behind in the church were killed with bayonets by the Costa Ricans .

Consequences. Cholera in Costa Rica

The armed forces on both sides suffered the following losses:

On the Costa Rican side:

- Fallen: 123, eleven of them officers , including General José Manuel Quirós y Blanco

- Wounded: 140

- Died at the Colera: 229.

On Walker's side:

- Liked: 58

- Wounded: 62

- Missed: 13.

In Walker's troop officers had fallen disproportionately, such as Captains Huston, Clinton, Horrell, and Linton, and Lieutenant Morgan, Stoll, Gay, Doyle, Gillies, and Winters.

Due to the heavy losses and the outbreak of cholera and the resulting panic , the planned march of the Costa Rican expedition army to Granada to overthrow Walker's regime had become an illusion. On April 26, 1856, Mora and the General Staff began to withdraw from Rivas. Mora's brother-in-law , General José María Cañas, stayed on site to organize the withdrawal of the troops. Although Karl (Carlos) Hoffmann , the surgeon for the Costa Rican troops, correctly identified the disease based on his experience in Germany, he assumed that the cause was the hot tropical climate of the Pacific coast and therefore advocated a return of the army to the cooler Costa Rican region Highlands.

The Guatemalan historian Soto V. compared the hardships of the withdrawal with the retreat of Napoleon Bonaparte's Grande Armée from Russia, with the difference that the Costa Ricans brought a deadly epidemic into their homeland. A total of 491 members of the 5,000–7,000-strong expedition army died of cholera. In Costa Rica, 8,607 people died out of a total population of around 112,000 at the time. The lowest mortality rate was 3.5% in the province of Guanacaste and the highest with 12.3% in the province of Cartago ; the national average was 8.2%.

The Costa Rican national hero Juan Santamaría

The Costa Rican national hero Juan Santamaría , who is said to have forced the mercenaries to withdraw by setting fire to the so-called Mesón de Guerra (home of the Guerra family) during the battle, is not mentioned in Walker 1860. Walker only reports that on the afternoon of April 11, 1856, the Costa Ricans set fire to some houses that were being held by the filibusters. Soto V. also stated in 1957 that not a single contemporary report even mentions Juan Santamaría, let alone that the act of an individual had influenced the outcome of the battle.

literature

- Raúl Francisco Arias Sánchez: Los soldados de la Campaña Nacional (1856–1857) , San José (UNED) 2007, ISBN 978-9968-31-546-3 .

- Frank Niess: The legacy of the Conquista. History of Nicaragua , Cologne (Pahl-Rugenstein) 1987. ISBN 3-7609-1058-0

- General e ingeniero Pedro Zamora Castellanos: Vida militar de Centro America , Tomo II, 2nd edition Guatemala City (Editorial del Ejército) 1967 (first edition ca.1922).

- William Walker: The War in Nicaragua , The University of Arizona Press 1985 (reprint of the original edition, Mobile, ALA 1860). ISBN 0-8165-0882-8 .

- Marco A. Soto V .: Guerra Nacional de Centroamerica , Guatemala City (Editorial del Ministerio de Educación Pública) 1957.

Web links

- TV broadcast about the 1856 National Campaign on Teletica Canal 7 from around 2007 on youtube.com

- TV broadcast Campana 1856–1857. Descubriendo hechos de nuestra historia , produced by the Ministerio de Educacion Publica (MEP) on youtube.com

- William Walker: The War in Nicaragua , digitized version of the original 1860 edition at latinamericanstudies.org

Individual evidence

- ^ Soto V., p. 60

- ↑ Walker, pp. 194f.

- ↑ Walker, p. 197, Soto V., p. 61, Zamora Castellanos, p. 79

- ↑ Walker, p. 199

- ↑ Walker, p. 200

- ^ Walker, p. 202

- ^ Zamora Castellanos, p. 87

- ^ Arias Sánchez, p. 89

- ↑ Walker, p. 203

- ^ Soto V., p. 69

- ^ Soto V., p. 70

- ↑ Arias Sánchez, pp. 105f.

- ↑ Walker, p. 201

- ↑ Soto V., p. 64