The Warehouse (New Orleans) and Polio: Difference between pages

Adding geodata: {{coord missing|United States}} |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Infobox Disease |

|||

'''The Warehouse''', located at 1820 [[Tchoupitoulas Street]], was the main [[Music venue|venue]] for rock music in [[New Orleans]] in the 1970s. |

|||

|Name = Poliomyelitis |

|||

|Image = Polio lores134.jpg |

|||

|Caption = A man with an [[Atrophy|atrophied]] right leg due to poliomyelitis |

|||

|ICD10 = {{ICD10|A|80||a|80}}, {{ICD10|B|91||b|90}} |

|||

|ICD9 = {{ICD9|045}}, {{ICD9|138}} |

|||

|DiseasesDB = 10209 |

|||

|MedlinePlus = 001402 |

|||

|eMedicineSubj = ped |

|||

|eMedicineTopic = 1843 |

|||

|eMedicine_mult = {{eMedicine2|pmr|6}} |

|||

|MeshName = Poliomyelitis |

|||

|MeshNumber = C02.182.600.700 |

|||

}} |

|||

'''Poliomyelitis''', often called '''polio''' or '''infantile paralysis''', is an acute [[virus (biology)|viral]] [[infectious disease]] spread from person to person, primarily via the [[fecal-oral route]].<ref name=Harrison>{{cite book| author = Cohen JI| chapter = Chapter 175: Enteroviruses and Reoviruses| title = [[Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine]]| editor = Kasper DL, Braunwald E, Fauci AS, ''et al'' (eds.)| edition = 16th ed.| publisher = McGraw-Hill Professional| year = 2004| pages = 1144| isbn = 0071402357 }}</ref> The term derives from the [[Greek language|Greek]] {{transl|el|''polio''}} ({{lang|el|πολίός}}), meaning "grey", {{transl|el|''myelon''}} ({{lang|el|µυελός}}), referring to the "[[spinal cord]]", and ''[[-itis]]'', which denotes [[inflammation]].<ref name=Chamberlin_2005>{{cite book | author = Chamberlin SL, Narins B (eds.) | title = The Gale Encyclopedia of Neurological Disorders | publisher = Thomson Gale | location = Detroit | year = 2005 | pages = 1859–70| isbn = 0-7876-9150-X}}</ref> Although around 90% of polio infections [[asymptomatic|cause no symptoms at all]], affected individuals can exhibit a range of symptoms if the virus enters the [[Blood|blood stream]].<ref name=Sherris>{{cite book | author = Ryan KJ, Ray CG (eds.) | chapter = Enteroviruses | title = Sherris Medical Microbiology | edition = 4th ed. | pages = 535–7 | publisher = McGraw Hill | year = 2004 | id = ISBN 0-8385-8529-9 }}</ref> In fewer than 1% of cases the virus enters the [[central nervous system]], preferentially infecting and destroying [[motor neuron]]s, leading to muscle weakness and acute [[flaccid paralysis]]. Different types of paralysis may occur, depending on the nerves involved. Spinal polio is the most common form, characterized by asymmetric paralysis that most often involves the legs. Bulbar polio leads to weakness of muscles innervated by [[cranial nerves]]. Bulbospinal polio is a combination of bulbar and spinal paralysis.<ref name = PinkBook>{{cite book | author = Atkinson W, Hamborsky J, McIntyre L, Wolfe S (eds.) | chapter = Poliomyelitis | title = Epidemiology and Prevention of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases (The Pink Book) | edition = 10th ed. | pages = 101–14 | publisher = Public Health Foundation | location =Washington DC |year = 2007 | url = http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/pinkbook/downloads/polio.pdf | format = PDF}}</ref> |

|||

The Warehouse opened on [[January 30]], [[1970]] with [[Fleetwood Mac]] followed the next night by the [[Grateful Dead]]. The [[Talking Heads]] performed there on closing night, [[September 10]], [[1982]]. In between those dates, the greats and soon-to-be greats of rock performed at The Warehouse. A partial list would include [[Bob Marley]], [[Chicago (band)|Chicago]], [[Kiss (band)|Kiss]], [[Pink Floyd]], [[The Who]], and [[ZZ Top]]. [[The Allman Brothers Band|The Allman Brothers]] were regulars. |

|||

Poliomyelitis was first recognized as a distinct condition by [[Jakob Heine]] in 1840.<ref name=Paul_1971>{{cite book| author = Paul JR| title=A History of Poliomyelitis| publisher=Yale University Press| location= New Haven, Conn| year=1971| pages=16–18| isbn= 0-300-01324-8| series= Yale studies in the history of science and medicine}}</ref> Its causative agent, [[poliovirus]], was identified in 1908 by [[Karl Landsteiner]].<ref name=Paul_1971/> Although major polio [[epidemic]]s were unknown before the late 19th century, polio was one of the most dreaded childhood diseases of the 20th century. Polio epidemics have crippled thousands of people, mostly young children; the disease has caused paralysis and death for much of human history. Polio had existed for thousands of years quietly as an [[endemic (epidemiology)|endemic]] pathogen until the 1880s, when major epidemics began to occur in Europe; soon after, widespread epidemics appeared in the United States.<ref name = Trevelyan/> By 1910, much of the world experienced a dramatic increase in polio cases and frequent epidemics became regular events, primarily in cities during the summer months. These epidemics—which left thousands of children and adults paralyzed—provided the impetus for a "Great Race" towards the development of a [[vaccine]]. The [[polio vaccine]]s developed by [[Jonas Salk]] in 1952 and [[Albert Sabin]] in 1962 are credited with reducing the global number of polio cases per year from many hundreds of thousands to around a thousand.<ref name=Aylward_2006>{{cite journal |author=Aylward R |title=Eradicating polio: today's challenges and tomorrow's legacy |journal=Ann Trop Med Parasitol |volume=100 |issue=5–6 |pages=401–13 |year=2006 |pmid=16899145 | doi = 10.1179/136485906X97354 <!--Retrieved from CrossRef by DOI bot-->}}</ref> Enhanced [[vaccination]] efforts led by the [[World Health Organization]], [[UNICEF]] and [[Rotary International]] could result in global eradication of the disease.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Heymann D |title=Global polio eradication initiative | url=http://209.85.215.104/search?q=cache:bdeN6aDyjY4J:www.scielosp.org/scielo.php%3Fscript%3Dsci_arttext%26pid%3DS0042-96862003000900020+site:scielosp.org+polio&hl=en&ct=clnk&cd=1&gl=us |journal=Bull. World Health Organ. |volume=84 |issue=8 |pages=595 |year=2006 |pmid=16917643 |doi=}}</ref> Yes, Eleni, you do have polio. <-- see we got to the point. |

|||

Rock history was made there. The Grateful Dead's arrest on opening weekend for drug possession would be immortalized in their song [[Truckin']]. [[Jim Morrison]]'s last concert with [[The Doors]] was at the Warehouse on [[December 12]], [[1970]]. |

|||

==Cause== |

|||

The Warehouse was originally called "A Warehouse" as it began in the 1850s as a cotton warehouse. Its non-heated or air conditioned space could legally hold slightly over 3,000 people. Its size was the reason for its popularity. If a band needed a larger place to play than a [[jazz club]], but couldn't fill a [[stadium]], they played at The Warehouse. |

|||

{{main|Poliovirus}} |

|||

[[Image:Polio EM PHIL 1875 lores.PNG|thumb|right|A [[Transmission electron microscopy|TEM]] [[micrograph]] of poliovirus]] |

|||

Poliomyelitis is caused by infection with a member of the [[genus]] ''[[Enterovirus]]'' known as [[poliovirus]] (PV). This group of [[RNA virus]]es prefers to inhabit the [[gastrointestinal tract]].<ref name=Harrison /> PV [[pathogen|infects and causes disease]] in humans alone.<ref name=Sherris /> Its [[Virus#Structure|structure]] is very simple, composed of a single [[sense (molecular biology)|(+) sense]] [[RNA]] [[genome]] enclosed in a protein shell called a [[capsid]].<ref name=Sherris /> In addition to protecting the virus’s genetic material, the capsid proteins enable poliovirus to infect certain types of cells. Three [[serovar|serotype]]s of poliovirus have been identified—poliovirus type 1 (PV1), type 2 (PV2), and type 3 (PV3)—each with a slightly different capsid protein.<ref>{{cite book |author=Katz, Samuel L.; Gershon, Anne A.; Krugman, Saul; Hotez, Peter J. |title=Krugman's infectious diseases of children |publisher=Mosby |location=St. Louis |year=2004 |pages=81–97 |isbn=0-323-01756-8 |oclc= |doi=}}</ref> All three are extremely [[virulence|virulent]] and produce the same disease symptoms.<ref name=Sherris /> PV1 is the most commonly encountered form, and the one most closely associated with paralysis.<ref name= Ohri/> |

|||

The Warehouse was finally demolished in April 1989. |

|||

Individuals who are exposed to the virus, either through infection or by [[immunization]] with polio vaccine, develop [[immunity (medical)|immunity]]. In immune individuals, [[IgA]] [[antibodies]] against poliovirus are present in the [[tonsil]]s and gastrointestinal tract and are able to block virus replication; [[IgG]] and [[IgM]] antibodies against PV can prevent the spread of the virus to motor neurons of the [[central nervous system]].<ref name=Kew_2005/> Infection or vaccination with one serotype of poliovirus does not provide immunity against the other serotypes, and full immunity requires exposure to each serotype.<ref name=Kew_2005/> |

|||

==External links== |

|||

==Transmission== |

|||

{{cite web |url= http://www.rockstarphotos.net/2007/01/24/photo-session-sidney-smith-as-told-to-brian-shupe-from-hittin-the-note-issue-50-2006/ |title= Photo Session: Sidney Smith - As told to Brian Shupe - From Hittin’ the Note - Issue 50 2006 }} |

|||

Poliomyelitis is highly contagious and spreads easily from human-to-human contact.<ref name=Kew_2005>{{cite journal |author=Kew O, Sutter R, de Gourville E, Dowdle W, Pallansch M |title=Vaccine-derived polioviruses and the endgame strategy for global polio eradication |journal=Annu Rev Microbiol |volume=59 |issue= |pages=587–635 |year=2005 |pmid=16153180 | doi = 10.1146/annurev.micro.58.030603.123625 <!--Retrieved from CrossRef by DOI bot-->}}</ref> In endemic areas, wild polioviruses can infect virtually the entire human population.<ref name=McGraw>{{cite book |author = Parker SP (ed.) | title = McGraw-Hill Concise Encyclopedia of Science & Technology |publisher=McGraw-Hill |location=New York |year=1998 | isbn=0-07-052659-1| page= 67}}</ref> It is seasonal in [[temperate climate]]s, with peak transmission occurring in summer and autumn.<ref name=Kew_2005 /> These seasonal differences are far less pronounced in [[tropical climate|tropical]] areas.<ref name=McGraw /> The time between first exposure and first symptoms, known as the [[incubation period]], is usually 6 to 20 days, with a maximum range of 3 to 35 days.<ref name=Racaniello>{{cite journal |author=Racaniello V |title=One hundred years of poliovirus pathogenesis |journal=[[Virology (journal)|Virology]] |volume=344 |issue=1 |pages=9–16 |year=2006 |pmid = 16364730 |doi=10.1016/j.virol.2005.09.015}}</ref> Virus particles are excreted in the [[feces]] for several weeks following initial infection.<ref name=Racaniello /> The disease is [[Transmission (medicine)|transmitted]] primarily via the [[fecal-oral route]], by ingesting contaminated food or water. It is occasionally transmitted via the oral-oral route,<ref name= Ohri>{{cite journal |last= Ohri |first=Linda K. |coauthors= Jonathan G. Marquess |year=1999 |title= Polio: Will We Soon Vanquish an Old Enemy? |journal= Drug Benefit Trends |volume= 11 |issue= 6|pages=41–54 |id= |url=http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/416890 |accessdate= 2008-08-23 }} (Available free on [[Medscape]]; registration required.)</ref> a mode especially visible in areas with good sanitation and hygiene.<ref name=Kew_2005 /> Polio is most infectious between 7–10 days before and 7–10 days after the appearance of symptoms, but transmission is possible as long as the virus remains in the saliva or feces.<ref name= Ohri/> |

|||

{{cite web |url= http://www.bestofneworleans.com/dispatch/2005-05-17/blake.html |title= BLAKE PONTCHARTRAIN, Jim Morrison's last concert with the Doors }} |

|||

Factors that increase the risk of polio infection or affect the severity of the disease include [[immune deficiency]],<ref>{{cite journal |author=Davis L, Bodian D, Price D, Butler I, Vickers J |title=Chronic progressive poliomyelitis secondary to vaccination of an immunodeficient child |journal=[[New England Journal of Medicine|N Engl J Med]] |volume=297 |issue=5 |pages=241–5 |year=1977 |pmid = 195206}}</ref> [[malnutrition]],<ref>{{cite journal |author=Chandra R |title=Reduced secretory antibody response to live attenuated measles and poliovirus vaccines in malnourished children| url= http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pubmed&pubmedid=1131622|journal=[[British Medical Journal|Br Med J]] |volume=2 |issue=5971 |pages=583–5 |year=1975 |pmid=1131622}}</ref> [[tonsillectomy]],<ref>{{cite journal |author=Miller A |title=Incidence of poliomyelitis; the effect of tonsillectomy and other operations on the nose and throat | url= http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pubmed&pubmedid=12978882 |journal=Calif Med |volume=77 |issue=1 |pages=19–21 |year=1952 |pmid=12978882}}</ref> physical activity immediately following the onset of paralysis,<ref>{{cite journal |author=Horstmann D |title=Acute poliomyelitis relation of physical activity at the time of onset to the course of the disease |journal=[[Journal of the American Medical Association|J Am Med Assoc]] |volume=142 |issue=4 |pages=236–41 |year=1950 |pmid=15400610}}</ref> skeletal muscle injury due to [[intramuscular injection|injection]] of vaccines or therapeutic agents,<ref>{{cite journal |author=Gromeier M, Wimmer E |title=Mechanism of injury-provoked poliomyelitis |url= http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pubmed&pubmedid=9573275| journal=J. Virol. |volume=72 |issue=6 |pages=5056–60 |year=1998 |pmid=9573275 |doi=}}</ref> and [[pregnancy]].<ref name= Evans_1960>{{cite journal |author=Evans C |title=Factors influencing the occurrence of illness during naturally acquired poliomyelitis virus infections | url=http://mmbr.asm.org/cgi/reprint/24/4/341.pdf | format = PDF | journal=Bacteriol Rev |volume=24 |issue=4 |pages=341–52 |year=1960 |pmid=13697553}}</ref> Although the virus can cross the [[placenta]] during pregnancy, the fetus does not appear to be affected by either maternal infection or polio vaccination.<ref name=UK>{{cite book |author=Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation (Salisbury A, Ramsay M, Noakes K (eds.) |title = Chapter 26:Poliomyelitis. ''in:'' Immunisation Against Infectious Disease, 2006 | url=http://www.immunisation.nhs.uk/files/GB_26_polio.pdf | format = PDF |publisher=[[Stationery Office]] |location=Edinburgh |year=2006 |pages = 313–29 |isbn = 0-11-322528-8}}</ref> Maternal antibodies also cross the [[placenta]], providing [[passive immunity]] that protects the infant from polio infection during the first few months of life.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Sauerbrei A, Groh A, Bischoff A, Prager J, Wutzler P |title=Antibodies against vaccine-preventable diseases in pregnant women and their offspring in the eastern part of Germany |journal=Med Microbiol Immunol |volume=190 |issue=4 |pages=167–72 |year=2002 |pmid=12005329 |doi=10.1007/s00430-001-0100-3}}</ref> |

|||

{{cite web |url= http://bt.etree.org/details.php?id=503771 |title= Audio: Grateful Dead- The Warehouse, New Orleans 1-31-70 }} |

|||

== Classification == |

|||

{{cite web |url= http://www.bestofneworleans.com/dispatch/2007-08-21/blake.php |title= BLAKE PONTCHARTRAIN, I know the Warehouse bar closed down, but does the building still exist? }} |

|||

{| class = "prettytable" style = "float:right; font-size:90%; margin-left:15px" |

|||

{{cite web |url= http://www.offbeat.com/artman/publish/article_783.shtml |title= A Brief History of New Orleans Rock }} |

|||

|+'''Outcomes of poliovirus infection''' |

|||

|- |

|||

! style="background:#efefef;" | Outcome |

|||

! style="background:#efefef" | Proportion of cases<ref name = PinkBook/> |

|||

|- |

|||

| Asymptomatic |

|||

| align="center" |90–95% |

|||

|- |

|||

| Minor illness |

|||

|align="center" |4–8% |

|||

|- |

|||

|Non-paralytic aseptic<br/> meningitis |

|||

| align="center" |1–2% |

|||

|- |

|||

|Paralytic poliomyelitis |

|||

| align="center" |0.1–0.5% |

|||

|- |

|||

|— Spinal polio |

|||

|align="center" |79% of paralytic cases |

|||

|- |

|||

|— Bulbospinal polio |

|||

|align="center" |19% of paralytic cases |

|||

|- |

|||

|— Bulbar polio |

|||

|align="center" |2% of paralytic cases |

|||

|} |

|||

The term ''poliomyelitis'' is used to identify the disease caused by any of the three [[Serovar|serotype]]s of poliovirus. Two basic patterns of polio infection are described: a minor illness which does not involve the [[central nervous system]] (CNS), sometimes called ''abortive poliomyelitis'', and a major illness involving the CNS, which may be paralytic or non-paralytic.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Falconer M, Bollenbach E |title=Late functional loss in nonparalytic polio |journal=American journal of physical medicine & rehabilitation / Association of Academic Physiatrists |volume=79 |issue=1 |pages=19–23 |year=2000 |pmid=10678598 |doi=10.1097/00002060-200001000-00006}}</ref> In most people with a [[immunocompetent|normal immune system]], a poliovirus infection is asymptomatic. Rarely the infection produces minor symptoms; these may include upper [[respiratory tract]] infection (sore throat and fever), [[gastrointestinal tract|gastrointestinal]] disturbances (nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, constipation or, rarely, diarrhea), and [[influenza]]-like illnesses.<ref name= PinkBook/> |

|||

{{coord missing|United States}} |

|||

The virus enters the central nervous system in about 3% of infections. Most patients with CNS involvement develop non-paralytic [[aseptic meningitis]], with symptoms of headache, neck, back, abdominal and extremity pain, fever, vomiting, [[lethargy]] and irritability.<ref name=Chamberlin_2005 /><ref name=Late>{{cite book | author=Leboeuf C | title=The late effects of Polio: Information For Health Care Providers. | url = http://www.health.qld.gov.au/polio/gp/GP_Manual.pdf| format=PDF | publisher=Commonwealth Department of Community Services and Health |year = 1992 |isbn=1-875412-05-0| accessdate=2008-08-23}}</ref> Approximately 1 in 200 to 1 in 1000 cases progress to [[paralytic]] disease, in which the muscles become weak, floppy and poorly-controlled, and finally completely paralyzed; this condition is known as [[Flaccid paralysis|acute flaccid paralysis]].<ref name=Henry1 /> Depending on the site of paralysis, paralytic poliomyelitis is classified as ''spinal'', ''bulbar'', or ''bulbospinal''. [[Encephalitis]], an infection of the brain tissue itself, can occur in rare cases and is usually restricted to infants. It is characterized by confusion, changes in mental status, headaches, fever, and less commonly [[seizure]]s and [[spastic paralysis]].<ref name= Encephalitis>{{cite book |author=Wood, Lawrence D. H.; Hall, Jesse B.; Schmidt, Gregory D. |title=Principles of Critical Care, Third Edition |publisher=McGraw-Hill Professional |location= |year=2005 |pages=870 |isbn=0-07-141640-4 |oclc= |doi=}}</ref> |

|||

{{DEFAULTSORT:Warehouse, The (New Orleans)}} |

|||

[[Category:Music venues in Louisiana]] |

|||

== Pathophysiology == |

|||

[[Category:Warehouses in the United States]] |

|||

[[Image:Polio spine.png|thumb|left|A blockage of the [[lumbar]] anterior spinal cord [[artery]] due to polio (PV3)]] |

|||

Poliovirus enters the body through the mouth, infecting the first cells it comes in contact with—the [[pharynx]] (throat) and [[intestinal mucosa]]. It gains entry by binding to a [[Immunoglobulin|immunoglobulin-like]] receptor, known as the poliovirus receptor or [[CD155]], on the cell surface.<ref name=He>{{cite journal |author=He Y, Mueller S, Chipman P, ''et al'' |title=Complexes of poliovirus serotypes with their common cellular receptor, CD155 | url= http://jvi.asm.org/cgi/content/full/77/8/4827?view=long&pmid=12663789 |journal=[[Journal of Virology|J Virol]] |volume=77 |issue=8 |pages = 4827–35 |year=2003 |pmid = 12663789 |doi=10.1128/JVI.77.8.4827-4835.2003}}</ref> The virus then hijacks the [[Host (biology)|host cell's]] own machinery, and begins to [[viral replication|replicate]]. Poliovirus divides within gastrointestinal cells for about a week, from where it spreads to the [[tonsils]] (specifically the [[follicular dendritic cell]]s residing within the tonsilar [[germinal center]]s), the intestinal [[lymphoid tissue]] including the [[M cell]]s of [[Peyer's patches]], and the deep [[Cervical lymph nodes|cervical]] and [[Inferior mesenteric lymph nodes|mesenteric lymph nodes]], where it multiplies abundantly. The virus is subsequently absorbed into the bloodstream.<ref name=Baron>{{cite book | author = Yin-Murphy M, Almond JW | chapter = Picornaviruses: The Enteroviruses: Polioviruses | title = Baron's Medical Microbiology'' (Baron S ''et al'', eds.)| edition = 4th ed. | publisher = Univ of Texas Medical Branch | year = 1996 | page= e-text| url= http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/bv.fcgi?rid=mmed.section.2862 | isbn = 0-9631172-1-1 }}</ref> |

|||

Known as [[viremia]], the presence of virus in the bloodstream enables it to be widely distributed throughout the body. Poliovirus can survive and multiply within the blood and lymphatics for long periods of time, sometimes as long as 17 weeks.<ref>{{cite web| author = Todar K | title = Polio | work = Ken Todar's Microbial World | publisher = University of Wisconsin - Madison | year = 2006 | url = http://bioinfo.bact.wisc.edu/themicrobialworld/homepage | accessdate = 2007-04-23}}</ref> In a small percentage of cases, it can spread and replicate in other sites such as [[brown fat]], the [[reticuloendothelial]] tissues, and muscle.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Sabin A |title=Pathogenesis of poliomyelitis; reappraisal in the light of new data |journal=[[Science (journal)|Science]] |volume=123 |issue=3209 |pages=1151–7 |year=1956 |pmid=13337331 |doi=10.1126/science.123.3209.1151}}</ref> This sustained replication causes a major viremia, and leads to the development of minor influenza-like symptoms. Rarely, this may progress and the virus may invade the central nervous system, provoking a local [[inflammatory response]]. In most cases this causes a self-limiting inflammation of the [[meninges]], the layers of tissue surrounding the [[brain]], which is known as ''non-paralytic aseptic meningitis''.<ref name=Chamberlin_2005 /> Penetration of the CNS provides no known benefit to the virus, and is quite possibly an incidental deviation of a normal gastrointestinal infection.<ref name= Mueller>{{cite journal |author=Mueller S, Wimmer E, Cello J |title=Poliovirus and poliomyelitis: a tale of guts, brains, and an accidental event |journal=Virus Res |volume=111 |issue=2 |pages=175–93 |year=2005 |pmid = 15885840 | doi = 10.1016/j.virusres.2005.04.008 <!--Retrieved from CrossRef by DOI bot-->}}</ref> The mechanisms by which poliovirus spreads to the CNS are poorly understood, but it appears to be primarily a chance event—largely independent of the age, gender, or [[Socioeconomics|socioeconomic]] position of the individual.<ref name=Mueller /> |

|||

===Paralytic polio=== |

|||

[[Image:PHIL 2767 Poliovirus Myotonic dystrophic changes.jpg|thumb|right|Denervation of [[skeletal muscle]] tissue secondary to poliovirus infection can lead to paralysis.]] |

|||

In around 1% of infections, poliovirus spreads along certain nerve fiber pathways, preferentially replicating in and destroying [[motor neuron]]s within the [[spinal cord]], [[brain stem]], or [[motor cortex]]. This leads to the development of paralytic poliomyelitis, the various forms of which (spinal, bulbar, and bulbospinal) vary only with the amount of neuronal damage and inflammation that occurs, and the region of the CNS that is affected. |

|||

The destruction of neuronal cells produces [[lesion]]s within the [[Dorsal root ganglion|spinal ganglia]]; these may also occur in the [[reticular formation]], [[vestibular nuclei]], [[cerebellar vermis]], and deep [[cerebellar nuclei]].<ref name=Mueller /> Inflammation associated with nerve cell destruction often alters the color and appearance of the gray matter in the [[spinal column]], causing it to appear reddish and swollen.<ref name=Chamberlin_2005/> Other destructive changes associated with paralytic disease occur in the [[forebrain]] region, specifically the [[hypothalamus]] and [[thalamus]].<ref name=Mueller /> The molecular mechanisms by which poliovirus causes paralytic disease are poorly understood. |

|||

Early symptoms of paralytic polio include high fever, headache, stiffness in the back and neck, asymmetrical weakness of various muscles, sensitivity to touch, difficulty swallowing, muscle pain, loss of superficial and deep [[reflex]]es, [[paresthesia]] (pins and needles), irritability, constipation, or difficulty urinating. Paralysis generally develops one to ten days after early symptoms begin, progresses for two to three days, and is usually complete by the time the fever breaks.<ref name= Silverstein>{{cite book |author = Silverstein A, Silverstein V, Nunn LS |title=Polio | series = Diseases and People | publisher=Enslow Publishers |location=Berkeley Heights, NJ |year=2001 |page= 12| isbn=0-7660-1592-0 }}</ref> |

|||

The likelihood of developing paralytic polio increases with age, as does the extent of paralysis. In children, non-paralytic meningitis is the most likely consequence of CNS involvement, and paralysis occurs in only 1 in 1000 cases. In adults, paralysis occurs in 1 in 75 cases.<ref name=Gawne_1995>{{cite journal | author = Gawne AC, Halstead LS | title = Post-polio syndrome: pathophysiology and clinical management | journal = Critical Review in Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation | year = 1995 | volume = 7 | pages = 147–88 | url = http://www.ott.zynet.co.uk/polio/lincolnshire/library/gawne/ppspandcm-s00.html}} Reproduced online with permission by Lincolnshire Post-Polio Library; retrieved on [[2007-11-10]].</ref> In children under five years of age, paralysis of one leg is most common; in adults, extensive paralysis of the [[chest]] and [[abdomen]] also affecting all four limbs—[[quadriplegia]]—is more likely.<ref name= Young>{{cite journal |author=Young GR |title=Occupational therapy and the postpolio syndrome | url= http://www.ott.zynet.co.uk/polio/lincolnshire/library/gryoung/otapps.html |journal=The American journal of occupational therapy |volume=43 |issue=2 |pages=97–103 |year=1989 |pmid=2522741 |doi=}}</ref> Paralysis rates also vary depending on the serotype of the infecting poliovirus; the highest rates of paralysis (1 in 200) are associated with poliovirus type 1, the lowest rates (1 in 2,000) are associated with type 2.<ref name=Nathanson>{{cite journal |author=Nathanson N, Martin J |title=The epidemiology of poliomyelitis: enigmas surrounding its appearance, epidemicity, and disappearance |journal=Am J Epidemiol |volume=110 |issue=6 |pages=672–92 |year=1979 |pmid=400274}}</ref> |

|||

==== Spinal polio ==== |

|||

[[Image:Polio spinal diagram.PNG|thumb|left|The location of [[motor neuron]]s in the [[Anterior horn (spinal cord)|anterior horn cells]] of the [[spinal column]].]] |

|||

Spinal polio is the most common form of paralytic poliomyelitis; it results from viral invasion of the motor neurons of the [[Anterior horn (spinal cord)|anterior horn cells]], or the [[anatomical terms of location#Dorsal and ventral|ventral]] (front) [[gray matter]] section in the [[spinal column]], which are responsible for movement of the muscles, including those of the [[torso|trunk]], [[limb (anatomy)|limb]]s and the [[intercostal muscle]]s.<ref name= Henry1>{{cite book | author = Frauenthal HWA, Manning JVV | title = Manual of infantile paralysis, with modern methods of treatment.| publisher = Philadelphia Davis | year = 1914| pages= 79–101 |url= http://books.google.com/books?vid=029ZCFMPZ0giNI1KiG6E&id=piyLQnuT-1YC&printsec=titlepage | oclc= 2078290}}</ref> Virus invasion causes inflammation of the nerve cells, leading to damage or destruction of motor neuron [[ganglion|ganglia]]. When spinal neurons die, [[Wallerian degeneration]] takes place, leading to weakness of those muscles formerly [[innervate]]d by the now dead neurons.<ref name=ConoJ /> With the destruction of nerve cells, the muscles no longer receive signals from the brain or spinal cord; without nerve stimulation, the muscles [[atrophy]], becoming weak, floppy and poorly controlled, and finally completely paralyzed.<ref name=Henry1 /> Progression to maximum paralysis is rapid (two to four days), and is usually associated with fever and muscle pain.<ref name= ConoJ>{{cite book | author = Cono J, Alexander LN | chapter = Chapter 10, Poliomyelitis. | title = Vaccine Preventable Disease Surveillance Manual | edition = 3rd ed. | pages = p. 10–1 | publisher = Centers for Disease Control and Prevention | year = 2002 | url = http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/surv-manual/downloads/chpt10_polio.pdf | format = PDF}}</ref> Deep [[tendon reflex|tendon]] [[reflex]]es are also affected, and are usually absent or diminished; [[sensation]] (the ability to feel) in the paralyzed limbs, however, is not affected.<ref name=ConoJ /> |

|||

The extent of spinal paralysis depends on the region of the cord affected, which may be [[cervical]], [[thoracic]], or [[lumbar]].<ref name=Guide>{{cite book |author= |title=Professional Guide to Diseases (Professional Guide Series) |publisher=Lippincott Williams & Wilkins |location=Hagerstown, MD |year= 2005|pages=243–5 |isbn=1-58255-370-X |oclc= |doi=}}</ref> The virus may affect muscles on both sides of the body, but more often the paralysis is [[Asymmetry|asymmetrical]].<ref name=Baron /> Any [[Limb (anatomy)|limb]] or combination of limbs may be affected—one leg, one arm, or both legs and both arms. Paralysis is often more severe [[proximal]]ly (where the limb joins the body) than [[distal]]ly (the [[fingertip]]s and [[toe]]s).<ref name=Baron /> |

|||

==== Bulbar polio ==== |

|||

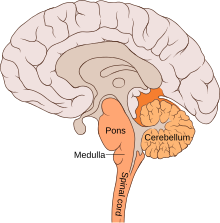

[[Image:Brain bulbar region.svg|thumb|right|The location and anatomy of the bulbar region (in orange)]] |

|||

Making up about 2% of cases of paralytic polio, bulbar polio occurs when poliovirus invades and destroys nerves within the [[bulbar]] region of the [[brain stem]].<ref name = PinkBook /> The bulbar region is a [[white matter]] pathway that connects the [[cerebral cortex]] to the brain stem. The destruction of these nerves weakens the muscles supplied by the [[cranial nerve]]s, producing symptoms of [[encephalitis]], and causes difficulty breathing, speaking and swallowing.<ref name=Late /> Critical nerves affected are the [[glossopharyngeal nerve]], which partially controls swallowing and functions in the throat, tongue movement and taste; the [[vagus nerve]], which sends signals to the heart, intestines, and lungs; and the [[accessory nerve]], which controls upper neck movement. Due to the effect on swallowing, secretions of [[mucus]] may build up in the airway causing suffocation.<ref name = Silverstein /> Other signs and symptoms include facial weakness, caused by destruction of the [[trigeminal nerve]] and [[facial nerve]], which innervate the cheeks, [[tear duct]]s, gums, and muscles of the face, among other structures; [[diplopia|double vision]]; difficulty in chewing; and abnormal respiratory rate, depth, and rhythm, which may lead to [[respiratory arrest]]. [[Pulmonary edema]] and [[shock (circulatory)|shock]] are also possible, and may be fatal.<ref name=Guide/> |

|||

==== Bulbospinal polio ==== |

|||

Approximately 19% of all paralytic polio cases have both bulbar and spinal symptoms; this subtype is called ''respiratory polio'' or ''bulbospinal polio''.<ref name= PinkBook /> Here the virus affects the upper part of the [[Cervical vertebrae|cervical spinal cord]] (C3 through C5), and paralysis of the [[Thoracic diaphragm|diaphragm]] occurs. The critical nerves affected are the [[phrenic nerve]], which drives the diaphragm to inflate the [[lungs]], and those that drive the muscles needed for swallowing. By destroying these nerves this form of polio affects breathing, making it difficult or impossible for the patient to breathe without the support of a [[medical ventilator|ventilator]]. It can lead to paralysis of the arms and legs and may also affect swallowing and heart functions.<ref name= Hoyt/> |

|||

== Diagnosis == |

|||

Paralytic poliomyelitis may be clinically suspected in individuals experiencing acute onset of flaccid paralysis in one or more limbs with decreased or absent tendon reflexes in the affected limbs, that cannot be attributed to another apparent cause, and without sensory or [[cognitive]] loss.<ref>{{cite journal |author= |title=Case definitions for infectious conditions under public health surveillance. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |url= ftp://ftp.cdc.gov/pub/Publications/mmwr/rr/rr4610.pdf |journal= Morbidity and mortality weekly report |volume=46 |issue=RR-10 |pages=26–7 |year=1997 |pmid=9148133 |doi=}}</ref> |

|||

A laboratory diagnosis is usually made based on recovery of poliovirus from a stool sample or a swab of the [[pharynx]]. [[Antibodies]] to poliovirus can be diagnostic, and are generally detected in the blood of infected patients early in the course of infection.<ref name=PinkBook /> Analysis of the patient's [[cerebrospinal fluid]] (CSF), which is collected by a [[lumbar puncture]] ("spinal tap"), reveals an increased number of [[white blood cell]]s (primarily [[lymphocyte]]s) and a mildly elevated protein level. Detection of virus in the CSF is diagnostic of paralytic polio, but rarely occurs.<ref name = PinkBook/> |

|||

If poliovirus is isolated from a patient experiencing acute flaccid paralysis, it is further tested through [[oligonucleotide]] mapping ([[genetic fingerprint]]ing), or more recently by [[polymerase chain reaction|PCR]] amplification, to determine whether it is "[[wild type]]" (that is, the virus encountered in nature) or "vaccine type" (derived from a strain of poliovirus used to produce polio vaccine).<ref>{{cite journal |author=Chezzi C |title=Rapid diagnosis of poliovirus infection by PCR amplification |url= http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pubmed&pubmedid=8784577| journal=[[Journal of Clinical Microbiology|J Clin Microbiol]] |volume=34 |issue=7 |pages=1722–5 |year=1996 |pmid=8784577}}</ref> It is important to determine the source of the virus because for each reported case of paralytic polio caused by wild poliovirus, it is estimated that another 200 to 3,000 contagious [[asymptomatic carrier]]s exist.<ref>{{cite journal |authorlink = Atul Gawande |author= Gawande A |title = The mop-up: eradicating polio from the planet, one child at a time | work = [[The New Yorker]] | issn = 0028-792X | pages = 34–40 | date = [[2004-01-12]]}}</ref> |

|||

==Prognosis== |

|||

Patients with abortive polio infections recover completely. In those that develop only aseptic meningitis, the symptoms can be expected to persist for two to ten days, followed by complete recovery.<ref name=Neumann/> In cases of spinal polio, if the affected nerve cells are completely destroyed, paralysis will be permanent; cells that are not destroyed but lose function temporarily may recover within four to six weeks after onset.<ref name=Neumann>{{cite journal |author=Neumann D |title=Polio: its impact on the people of the United States and the emerging profession of physical therapy |url= http://www.post-polio.org/edu/hpros/Aug04HistPersNeumann.pdf | format = PDF | journal=The Journal of orthopaedic and sports physical therapy |volume=34 |issue=8 |pages=479–92 |year=2004 |pmid=15373011}} Reproduced online with permission by Post-Polio Health International; retrieved on [[2007-11-10]].</ref> Half the patients with spinal polio recover fully, one quarter recover with mild disability and the remaining quarter are left with severe disability.<ref>{{cite book |author=Cuccurullo SJ |title=Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Board Review |url= http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/bv.fcgi?&rid=physmedrehab.table.8357 | publisher=Demos Medical Publishing | year = 2004 |isbn=1-888799-45-5}}</ref> The degree of both acute paralysis and residual paralysis is likely to be proportional to the degree of [[viremia]], and [[Proportionality (mathematics)#Inverse proportionality|inversely proportional]] to the degree of [[immunity (medical)|immunity]].<ref name= Mueller/> Spinal polio is rarely fatal.<ref name=Silverstein /> |

|||

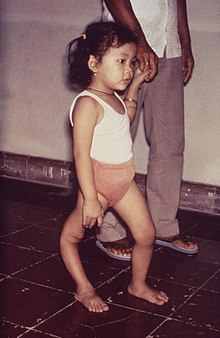

[[Image:Polio sequelle.jpg|thumb|A child with a deformity of her right leg due to polio]] |

|||

Without respiratory support, consequences of poliomyelitis with [[Respiration (physiology)|respiratory]] involvement include [[suffocation]] or [[aspiration pneumonia|pneumonia from aspiration of secretions]].<ref name= Goldberg>{{cite journal |author=Goldberg A |title=Noninvasive mechanical ventilation at home: building upon the tradition |doi= 10.1378/chest.121.2.321 |journal=[[Chest (journal)|Chest]] |volume=121 |issue=2 |pages=321–4 |year=2002 |pmid=11834636}}</ref> Overall, 5–10% of patients with paralytic polio die due to the paralysis of muscles used for breathing. The mortality rate varies by age: 2–5% of children and up to 15–30% of adults die.<ref name= PinkBook /> Bulbar polio often causes death if respiratory support is not provided;<ref name= Hoyt /> with support, its mortality rate ranges from 25 to 75%, depending on the age of the patient.<ref name=PinkBook /><ref>{{cite journal |author=Miller AH, Buck LS |title=Tracheotomy in bulbar poliomyelitis |url= http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/pagerender.fcgi?artid=1520308&pageindex=1#page |journal=California medicine |volume=72 |issue=1 |pages=34–6 |year=1950 |pmid=15398892 |doi=}}</ref> When positive pressure ventilators are available, the mortality can be reduced to 15%.<ref name=Wackers>{{cite paper| author = Wackers, G.| title = Constructivist Medicine| version = PhD-thesis| publisher = Maastricht: Universitaire Pers Maastricht| year = 1994| url = http://www.fdcw.unimaas.nl/personal/WebSitesMWT/Wackers/proefschrift.html#h4| format = [[World Wide Web|web]]| accessdate = 2008-01-04 }}</ref> |

|||

===Recovery=== |

|||

Many cases of poliomyelitis result in only temporary paralysis.<ref name=Henry1 /> Nerve impulses return to the formerly paralyzed muscle within a month, and recovery is usually complete in six to eight months.<ref name=Neumann /> The [[neurophysiology|neurophysiological]] processes involved in recovery following acute paralytic poliomyelitis are quite effective; muscles are able to retain normal strength even if half the original motor neurons have been lost.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Sandberg A, Hansson B, Stålberg E |title=Comparison between concentric needle EMG and macro EMG in patients with a history of polio |journal=Clinical Neurophysiology |volume=110 |issue=11 |pages=1900–8 |year=1999 |pmid=10576485 | doi = 10.1016/S1388-2457(99)00150-9 <!--Retrieved from CrossRef by DOI bot-->}}</ref> Paralysis remaining after one year is likely to be permanent, although modest recoveries of muscle strength are possible 12 to 18 months after infection.<ref name=Neumann /> |

|||

One mechanism involved in recovery is nerve terminal sprouting, in which remaining brainstem and spinal cord motor neurons develop new branches, or ''axonal sprouts''.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Cashman NR, Covault J, Wollman RL, Sanes JR |title=Neural cell adhesion molecule in normal, denervated, and myopathic human muscle |journal=Ann. Neurol. |volume=21 |issue=5 |pages=481–9 |year=1987 |pmid=3296947 | doi = 10.1002/ana.410210512 <!--Retrieved from CrossRef by DOI bot-->}}</ref> These sprouts can [[reinnervate]] orphaned muscle fibers that have been denervated by acute polio infection,<ref name=Agre>{{cite journal |author=Agre JC, Rodríquez AA, Tafel JA |title=Late effects of polio: critical review of the literature on neuromuscular function |journal=Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation |volume=72 |issue=11 |pages=923–31 |year=1991 |pmid=1929813 | doi = 10.1016/0003-9993(91)90013-9 <!--Retrieved from CrossRef by DOI bot-->}}</ref> restoring the fibers' capacity to contract and improving strength.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Trojan DA, Cashman NR |title=Post-poliomyelitis syndrome |journal=Muscle Nerve |volume=31 |issue=1 |pages=6–19 |year=2005 |pmid=15599928 | doi = 10.1002/mus.20259 <!--Retrieved from CrossRef by DOI bot-->}}</ref> Terminal sprouting may generate a few significantly enlarged motor neurons doing work previously performed by as many as four or five units:<ref name=Gawne_1995 /> a single motor neuron that once controlled 200 muscle cells might control 800 to 1000 cells. Other mechanisms that occur during the rehabilitation phase, and contribute to muscle strength restoration, include [[muscle hypertrophy|myofiber hypertrophy]]—enlargement of muscle fibers through exercise and activity—and transformation of [[Muscle fiber#Type II|type II muscle fibers]] to [[Muscle fiber#Type I| type I muscle fibers]].<ref name=Agre /><ref name = Grimby_1989>{{cite journal |author=Grimby G, Einarsson G, Hedberg M, Aniansson A |title=Muscle adaptive changes in post-polio subjects |journal=Scandinavian journal of rehabilitation medicine |volume=21 |issue=1 |pages=19–26 |year=1989 |pmid=2711135}}</ref> |

|||

In addition to these physiological processes, the body possesses a number of compensatory mechanisms to maintain function in the presence of residual paralysis. These include the use of weaker muscles at a higher than usual intensity relative to the [[Muscle contraction#Contractions, by muscle type|muscle's maximal capacity]], enhancing athletic development of previously little-used muscles, and using [[ligament]]s for stability, which enables greater mobility.<ref name = Grimby_1989 /> |

|||

===Complications=== |

|||

Residual complications of paralytic polio often occur following the initial recovery process.<ref name= Late /> Muscle [[paresis]] and paralysis can sometimes result in [[skeletal]] deformities, tightening of the joints and movement disability. Once the muscles in the limb become flaccid, they may interfere with the function of other muscles. A typical manifestation of this problem is [[equinus foot]] (similar to [[club foot]]). This deformity develops when the muscles that pull the toes downward are working, but those that pull it upward are not, and the foot naturally tends to drop toward the ground. If the problem is left untreated, the [[Achilles tendon]]s at the back of the foot retract and the foot cannot take on a normal position. Polio victims that develop equinus foot cannot walk properly because they cannot put their heel on the ground. A similar situation can develop if the arms become paralyzed.<ref name= Aftereffects>{{cite web | author = Sanofi Pasteur | title = Poliomyelitis virus (picornavirus, enterovirus), after-effects of the polio, paralysis, deformations | work = Polio Eradication | url = http://www.polio.info/polio-eradication/front/index.jsp?siteCode=POLIO&lang=EN&codeRubrique=14 | accessdate = 2008-08-23}}</ref> In some cases the growth of an affected leg is slowed by polio, while the other leg continues to grow normally. The result is that one leg is shorter than the other and the person limps and leans to one side, in turn leading to deformities of the spine (such as [[scoliosis]]).<ref name= Aftereffects /> [[Osteoporosis]] and increased likelihood of [[bone fracture]]s may occur. Extended use of braces or wheelchairs may cause compression [[neuropathy]], as well as a loss of proper function of the [[vein]]s in the legs, due to pooling of blood in paralyzed lower limbs.<ref name=MayoComps>{{cite web |author = Mayo Clinic Staff | date=[[2005-05-19]] | url = http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/polio/DS00572/DSECTION=complications | title = Polio: Complications| publisher = Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research (MFMER)| accessdate=2007-02-26}}</ref><ref name= Hoyt>{{cite book |author=Hoyt, William Graves; Miller, Neil; Walsh, Frank |title=Walsh and Hoyt's clinical neuro-ophthalmology |publisher=Lippincott Williams & Wilkins |location=Hagerstown, MD |year=2005 |pages=3264–65 |isbn=0-7817-4814-3 |oclc= |doi=}}</ref> Complications from prolonged immobility involving the [[lungs]], [[kidney]]s and [[heart]] include [[pulmonary edema]], [[aspiration pneumonia]], [[urinary tract infection]]s, [[kidney stone]]s, [[paralytic ileus]], [[myocarditis]] and [[cor pulmonale]].<ref name=MayoComps /><ref name= Hoyt/> |

|||

=== Post-polio syndrome === |

|||

{{main|Post-polio syndrome}} |

|||

Around a quarter of individuals who survive paralytic polio in childhood develop additional symptoms decades after recovering from the acute infection, notably muscle weakness, extreme fatigue, or paralysis. This condition is known as [[post-polio syndrome]] (PPS).<ref name=Cashman>{{cite journal |author=Trojan D, Cashman N |title=Post-poliomyelitis syndrome |journal=Muscle Nerve |volume=31 |issue=1 |pages=6–19 |year=2005 |pmid = 15599928 | doi = 10.1002/mus.20259 <!--Retrieved from CrossRef by DOI bot-->}}</ref> The symptoms of PPS are thought to involve a failure of the over-sized motor units created during recovery from paralytic disease.<ref name=Ramlow_1992>{{cite journal |author=Ramlow J, Alexander M, LaPorte R, Kaufmann C, Kuller L |title=Epidemiology of the post-polio syndrome |journal=Am. J. Epidemiol. |volume=136 |issue=7 |pages=769–86 |year=1992 |pmid=1442743}}</ref><ref name= Annals>{{cite journal |author=Lin K, Lim Y |title=Post-poliomyelitis syndrome: case report and review of the literature| url= http://www.annals.edu.sg/pdf/34VolNo7200508/V34N7p447.pdf | format = PDF |journal=Ann Acad Med Singapore |volume=34 |issue=7 |pages=447–9 |year=2005 |pmid = 16123820}}</ref> Factors that increase the risk of PPS include the length of time since acute poliovirus infection, the presence of permanent residual impairment after recovery from the acute illness, and both overuse and disuse of neurons.<ref name=Cashman /> Post-polio syndrome is not an infectious process, and persons experiencing the syndrome do not shed poliovirus.<ref name=PinkBook /> |

|||

== Treatment == |

|||

[[Image:Womanonsideinlung.jpg|thumb|left|A modern negative pressure ventilator (iron lung)]] |

|||

There is no [[cure]] for polio. The focus of modern treatment has been on providing relief of symptoms, speeding recovery and preventing complications. Supportive measures include [[antibiotics]] to prevent infections in weakened muscles, [[analgesics]] for pain, moderate exercise and a nutritious diet.<ref name=Daniel>{{cite book |author=Daniel, Thomas M.; Robbins, Frederick C. |title=Polio |publisher=University of Rochester Press |location=Rochester, N.Y., USA |year= 1997 |pages= 8–10 |isbn=1-58046-066-6 |oclc= |doi=}}</ref> Treatment of polio often requires long-term rehabilitation, including [[physical therapy]], braces, corrective shoes and, in some cases, [[orthopedic surgery]].<ref name=Guide /> |

|||

Portable [[ventilator]]s may be required to support breathing. Historically, a noninvasive negative-pressure ventilator, more commonly called an [[iron lung]], was used to artificially maintain respiration during an acute polio infection until a person could breathe independently (generally about one to two weeks). Today many polio survivors with permanent respiratory paralysis use modern [[Biphasic Cuirass Ventilation|jacket-type]] negative-pressure ventilators that are worn over the chest and abdomen.<ref name= Goldberg /> |

|||

Other [[History of poliomyelitis#Historical treatments|historical treatments for polio]] include [[hydrotherapy]], [[electrotherapy]], massage and passive motion exercises, and surgical treatments such as tendon lengthening and nerve grafting.<ref name=Henry1 /> Devices such as rigid [[brace (orthopaedic)|brace]]s and body casts—which tended to cause [[muscle atrophy]] due to the limited movement of the user—were also touted as effective treatments.<ref name = Oppewal>{{cite journal |author=Oppewal S |title=Sister Elizabeth Kenny, an Australian nurse, and treatment of poliomyelitis victims |journal=Image J Nurs Sch |volume=29 |issue=1 |pages=83–7 |year=1997 |pmid=9127546 |doi=10.1111/j.1547-5069.1997.tb01145.x}}</ref> |

|||

==Prevention== |

|||

=== Passive immunization === |

|||

In 1950, [[William Hammon]] at the [[University of Pittsburgh]] purified the [[gamma globulin]] component of the [[blood plasma]] of polio survivors.<ref name=Hammon_1955>{{cite journal |author=Hammon W |title=Passive immunization against poliomyelitis |journal=Monogr Ser World Health Organ |volume=26 |issue= |pages=357–70 |year = 1955 |pmid=14374581}}</ref> Hammon proposed that the gamma globulin, which contained antibodies to poliovirus, could be used to halt poliovirus infection, prevent disease, and reduce the severity of disease in other patients who had contracted polio. The results of a large [[clinical trial]] were promising; the gamma globulin was shown to be about 80% effective in preventing the development of paralytic poliomyelitis.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Hammon W, Coriell L, Ludwig E, ''et al'' |title=Evaluation of Red Cross gamma globulin as a prophylactic agent for poliomyelitis. 5. Reanalysis of results based on laboratory-confirmed cases |journal=J Am Med Assoc |volume=156 |issue=1 |pages=21–7 |year=1954 |pmid=13183798}}</ref> It was also shown to reduce the severity of the disease in patients that developed polio.<ref name=Hammon_1955 /> The gamma globulin approach was later deemed impractical for widespread use, however, due in large part to the limited supply of blood plasma, and the medical community turned its focus to the development of a polio vaccine.<ref name=Rinaldo>{{cite journal |author=Rinaldo C |title=Passive immunization against poliomyelitis: the Hammon gamma globulin field trials, 1951–1953 |journal=[[American Journal of Public Health|Am J Public Health]] |volume=95 |issue=5 |pages=790–9 |year=2005 |pmid=15855454}}</ref> |

|||

=== Vaccine === |

|||

{{main|Polio vaccine}} |

|||

[[Image:Poliodrops.jpg|thumb|right|A child receives oral polio vaccine]] |

|||

Two vaccines are used throughout the world to combat [[polio]]. Both vaccines induce immunity to polio, efficiently blocking person-to-person transmission of wild poliovirus, thereby protecting both individual vaccine recipients and the wider community (so-called [[herd immunity]]).<ref name=Fine>{{cite journal |author=Fine P, Carneiro I |title=Transmissibility and persistence of oral polio vaccine viruses: implications for the global poliomyelitis eradication initiative |url= http://aje.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/reprint/150/10/1001| journal=Am J Epidemiol |volume=150 |issue=10 |pages=1001–21 |year=1999 |pmid=10568615}}</ref> |

|||

The first polio vaccine was developed in 1952 by [[Jonas Salk]], also at the University of Pittsburgh, and announced to the world on April 12, 1955.<ref name= Spice>{{cite news | author = Spice B |title=Tireless polio research effort bears fruit and indignation |url=http://www.post-gazette.com/pg/05094/482468.stm |format= |work=The Salk vaccine: 50 years later/ second of two parts |publisher= [[Pittsburgh Post-Gazette]]|date= April 4, 2005 |accessdate= 2008-08-23 }}</ref> The Salk vaccine, or inactivated poliovirus vaccine (IPV), is based on poliovirus grown in a type of monkey kidney tissue culture ([[Vero cell]] [[cell culture|line]]), which is chemically inactivated with [[formalin]].<ref name=Kew_2005 /> After two doses of IPV (given by [[injection (medicine)|injection]]), 90% or more of individuals develop protective antibody to all three [[serotype]]s of poliovirus, and at least 99% are immune to poliovirus following three doses.<ref name = PinkBook /> |

|||

Subsequently, [[Albert Sabin]] developed an oral polio vaccine (OPV) using live but weakened ([[attenuated]]) virus, produced by the repeated passage of the virus through non-human cells at sub-[[physiological]] temperatures.<ref name=Sabin_1973>{{cite journal | author = Sabin AB, Boulger LR | title = History of Sabin attenuated poliovirus oral live vaccine strains | journal = J Biol Stand | year = 1973 | volume = 1 | pages = 115–8 | doi = 10.1016/0092-1157(73)90048-6 <!--Retrieved from CrossRef by DOI bot-->}}</ref> [[Clinical trial|Human trials]] of Sabin's vaccine began in 1957 and it was licensed in 1962.<ref>{{cite web | title = A Science Odyssey: People and Discoveries | publisher = PBS | year = 1998 | url = http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aso/databank/entries/dm52sa.html | accessdate = 2008-08-23}}</ref> The attenuated poliovirus in the Sabin vaccine replicates very efficiently in the gut, the primary site of wild poliovirus infection and replication, but the vaccine strain is unable to replicate efficiently within [[nervous system]] tissue.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Sabin A, Ramos-Alvarez M, Alvarez-Amezquita J, ''et al'' |title=Live, orally given poliovirus vaccine. Effects of rapid mass immunization on population under conditions of massive enteric infection with other viruses |journal=[[Journal of the American Medical Association|JAMA]] |volume=173 |issue= |pages=1521–6 |year=1960 |pmid =14440553}}</ref> A single dose of oral polio vaccine produces immunity to all three poliovirus serotypes in approximately 50% of recipients. Three doses of live-attenuated OPV produce protective antibody to all three poliovirus types in more than 95% of recipients.<ref name=PinkBook /> |

|||

Because OPV is inexpensive, easy to administer, and produces excellent immunity in the intestine (which helps prevent infection with wild virus in areas where it is [[Endemic (epidemiology)|endemic]]), it has been the vaccine of choice for controlling poliomyelitis in many countries.<ref name=Peds>{{cite journal |author= |title=Poliomyelitis prevention: recommendations for use of inactivated poliovirus vaccine and live oral poliovirus vaccine. American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Infectious Diseases | url=http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/cgi/content/full/99/2/300 |journal=[[Pediatrics (journal)|Pediatrics]] |volume=99 |issue=2 |pages=300–5 |year=1997 |pmid=9024465|doi=10.1542/peds.99.2.300}}</ref> On very rare occasions (about 1 case per 750,000 vaccine recipients) the attenuated virus in OPV reverts into a form that can paralyze.<ref name=Racaniello/> Most [[Developed country|industrialized countries]] have switched to IPV, which cannot revert, either as the sole vaccine against poliomyelitis or in combination with oral polio vaccine.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.who.int/ith/vaccines/2007_routine_use/en/index11.html |title=WHO: Vaccines for routine use |accessdate=2008-08-23 |page= 12| format= |work= International travel and health}}</ref> |

|||

== Eradication == |

|||

{{main|Poliomyelitis eradication}} |

|||

Following the widespread use of poliovirus vaccine in the mid-1950s, the incidence of poliomyelitis declined dramatically in many industrialized countries. A global effort to eradicate polio began in 1988, led by the [[World Health Organization]], [[UNICEF]], and [[The Rotary Foundation]].<ref name=Watch>{{cite web| last = Mastny| first = Lisa | title = Eradicating Polio: A Model for International Cooperation |publisher = Worldwatch Institute | date = January 25, 1999 | url = http://www.worldwatch.org/node/1644 | accessdate = 2008-08-23}}</ref> These efforts have reduced the number of annual diagnosed cases by 99%; from an estimated 350,000 cases in 1988 to 1,310 cases in 2007.<ref name=eradication>{{cite journal |author= |title=Update on vaccine-derived polioviruses |journal=[[Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report|MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep]] |volume=55 |issue=40 |pages=1093–7 |year=2006 |pmid=17035927}}</ref><ref name=morbidity>{{cite web|url=http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5718a4.htm|title=Progress Toward Interruption of Wild Poliovirus Transmission --- Worldwide, January 2007--April 2008|work=Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report|publisher=[[Centers for Disease Control and Prevention]]|date=[[2008-05-09]]|accessdate=2008-08-23 }}</ref> Should eradication be successful it will represent only the second time mankind has ever completely eliminated a disease. The first such disease was [[smallpox]], which was officially eradicated in 1979.<ref name=WHO_smallpox>{{cite web | title=Smallpox | work=WHO Factsheet | url=http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/smallpox/en/ | accessdate = 2008-08-23}}</ref> A number of eradication milestones have already been reached, and several regions of the world have been certified polio-free. The [[Americas]] were declared polio-free in 1994.<ref name=MMWR_1994>{{cite journal| author= | title = International Notes Certification of Poliomyelitis Eradication—the Americas, 1994 | journal = MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep | publisher = Centers for Disease Control and Prevention | volume= 43 | issue= 39 | pages = 720–2 | year=1994 | url = http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/00032760.htm | pmid = 7522302 }}</ref> In 2000 polio was officially eradicated in 36 Western Pacific countries, including China and Australia.<ref name= Pacific>{{cite journal | author = ,| title = General News. Major Milestone reached in Global Polio Eradication: Western Pacific Region is certified Polio-Free | journal = Health Educ Res | year = 2001 | volume = 16 | issue = 1 | pages = p. 109 | url= http://her.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/reprint/16/1/109.pdf | format = PDF| doi = 10.1093/her/16.1.109}}</ref><ref name="D'Souza_2002">{{cite journal |author=D'Souza R, Kennett M, Watson C |title=Australia declared polio free |journal=Commun Dis Intell |volume=26 |issue=2 |pages=253–60 |year=2002 |pmid=12206379}}</ref> [[Europe]] was declared polio-free in 2002.<ref name=WHO_Europe_2002>{{cite press release | title = Europe achieves historic milestone as Region is declared polio-free | publisher = European Region of the World Health Organization | date = [[2002-06-21]] | url = http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/releases/releaseeuro02/en/index.html | accessdate = 2008-08-23 }}</ref> As of 2006, polio remains [[Endemic (epidemiology)|endemic]] in only four countries: [[Nigeria]], [[India]], [[Pakistan]], and [[Afghanistan]].<ref name=eradication/> |

|||

Much of this work was documented by Brazilian photographer [[Sebastião Salgado]], as a [[List of UNICEF Goodwill Ambassadors|UNICEF Goodwill Ambassador]], in the book ''The End of Polio: Global Effort to End a Disease''.<ref>{{cite press release | title = The End of Polio: Photographs of Sebastião Salgado Opens to Public | url = http://www.cdc.gov/media/pressrel/2007/r070824.htm | date = August 24, 2007 | accessdate = 2008-06-02 | publisher = Centers for Disease Control and Prevention}}</ref> |

|||

== History == |

|||

{{main|History of poliomyelitis}} |

|||

[[Image:Polio Egyptian Stele.jpg|thumb|right|An [[Egypt]]ian [[stele]] thought to represent a polio victim, [[18th Dynasty]] (1403–1365 BC)]] |

|||

The effects of polio have been known since [[prehistory]]; [[Ancient Egypt|Egyptian]] paintings and carvings depict otherwise healthy people with withered limbs, and children walking with canes at a young age.<ref name=Paul_1971/> The first clinical description was provided by the English physician Michael Underwood in 1789, where he refers to polio as "a debility of the lower extremities".<ref name=Underwood_1789>{{cite book | last = Underwood | first = Michael | title = Debility of the lower extremities. ''In:'' A treatise on the diseases <nowiki>[sic]</nowiki> of children, with general directions for the management of infants from the birth (1789) | volume = 2 | publisher = Philadelphia: Printed by T. Dobson, no. 41, South Second-Street | year = 1793 | pages = pp. 254–6 | series = Early American Imprints, 1st series, no. 26291 (filmed); Copyright 2002 by the American Antiquarian Society | url=http://catalog.mwa.org/cgi-bin/Pwebrecon.cgi?v1=1&ti=1,1&Search%5FArg=Underwood%2C%20Michael&Search%5FCode=OPAU&CNT=10&PID=23682&SEQ=20070223225426&SID=1 | format = fee required | accessdate = 2008-08-23 }}</ref> The work of physicians [[Jakob Heine]] in 1840 and [[Karl Oskar Medin]] in 1890 led to it being known as ''Heine-Medin disease''.<ref name=Pearce_2005>{{cite journal |author=Pearce J |title=Poliomyelitis (Heine-Medin disease) |journal=J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry |volume=76 |issue=1 |pages=128 |year=2005 |doi= 10.1136/jnnp.2003.028548 | pmid=15608013}}</ref> The disease was later called ''infantile paralysis'', based on its propensity to affect children. |

|||

Before the 20th century, polio infections were rarely seen in infants before six months of age, most cases occurring in children six months to four years of age.<ref name=Robertson_1993>{{cite web | author = Robertson S | title = Module 6: Poliomyelitis | work = The Immunological Basis for Immunization Series| publisher = World Health Organization. Geneva, Switzerland. | url = http://www.who.int/vaccines-documents/DocsPDF-IBI-e/mod6_e.pdf | format = PDF | year = 1993 | accessdate = 2008-08-23}}</ref> Poorer [[sanitation]] of the time resulted in a constant exposure to the virus, which enhanced a natural [[immunity (medical)|immunity]] within the population. In developed countries during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, improvements were made in community sanitation, including better [[sewage]] disposal and clean water supplies. These changes drastically increased the proportion of children and adults at risk of paralytic polio infection, by reducing childhood exposure and immunity to the disease. |

|||

Small localized paralytic polio [[epidemic]]s began to appear in Europe and the United States around 1900.<ref name = Trevelyan>{{cite journal |author=Trevelyan B, Smallman-Raynor M, Cliff A |title=The Spatial Dynamics of Poliomyelitis in the United States: From Epidemic Emergence to Vaccine-Induced Retreat, 1910–1971| url= http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pubmed&pubmedid=16741562 |journal=Ann Assoc Am Geogr |volume=95 |issue=2 |pages=269–293 |year=2005 |pmid=16741562 | doi = 10.1111/j.1467-8306.2005.00460.x <!--Retrieved from CrossRef by DOI bot-->}}</ref> Outbreaks reached [[pandemic]] proportions in Europe, North America, Australia, and New Zealand during the first half of the 20th century. By 1950 the peak age incidence of paralytic poliomyelitis in the United States had shifted from infants to children aged five to nine years, when the risk of paralysis is greater; about one-third of the cases were reported in persons over 15 years of age.<ref name=Melnick_1990>{{cite book | author = Melnick JL | title = Poliomyelitis. In: Tropical and Geographical Medicine| edition = 2nd ed. | publisher = McGraw-Hill | year =1990 | pages = p. 558–76 | isbn = 007068328X }}</ref> Accordingly, the rate of paralysis and death due to polio infection also increased during this time.<ref name = Trevelyan/> In the United States, the 1952 polio epidemic became the worst outbreak in the nation's history. Of nearly 58,000 cases reported that year 3,145 died and 21,269 were left with mild to disabling paralysis.<ref name=Zamula>{{cite journal |author= Zamula E|title=A New Challenge for Former Polio Patients | url= http://www.fda.gov/bbs/topics/CONSUMER/CON00006.html |journal= FDA Consumer |volume = 25 |issue = 5 |pages = 21–5 |year=1991}}</ref> |

|||

The polio epidemics changed not only the lives of those who survived them, but also affected profound cultural changes; spurring [[grassroots]] fund-raising campaigns that would revolutionize medical [[philanthropy]], and giving rise to the modern field of [[Physical therapy|rehabilitation therapy]]. As one of the largest disabled groups in the world polio survivors also helped to advance the modern [[disability rights movement]] through campaigns for the social and civil rights of the [[disabled]]. The World Health Organization estimates that there are 10 to 20 million polio survivors worldwide.<ref name= NewsDesk>{{cite web | title = After Effects of Polio Can Harm Survivors 40 Years Later | publisher = March of Dimes | url = http://www.marchofdimes.com/aboutus/791_1718.asp | date = [[2001-06-01]] | accessdate = 2008-08-23}}</ref> In 1977 there were 254,000 persons living in the United States who had been paralyzed by polio.<ref>{{cite journal | author = Frick NM, Bruno RL | title = Post-polio sequelae: physiological and psychological overview | journal = Rehabilitation literature | volume = 47 | issue = 5–6 | pages = 106–11 | year = 1986 | pmid = 3749588 | doi = }}</ref> According to doctors and local polio support groups, some 40,000 polio survivors with varying degrees of paralysis live in Germany, 30,000 in Japan, 24,000 in France, 16,000 in Australia, 12,000 in Canada and 12,000 in the United Kingdom.<ref name= NewsDesk/> Many [[List of polio survivors|notable individuals have survived polio]] and often credit the prolonged immobility and residual paralysis associated with polio as a driving force in their lives and careers.<ref>{{cite book |author=Richard L. Bruno |title=The Polio Paradox: Understanding and Treating "Post-Polio Syndrome" and Chronic Fatigue |publisher=Warner Books |location=New York |year=2002 |pages= 105–6|isbn=0-446-69069-4 |oclc= |doi=}}</ref> |

|||

The disease was very well publicized during the polio epidemics of the 1950s, with extensive media coverage of any scientific advancements that might lead to a cure. Thus, the scientists working on polio became some of the most famous of the century. Fifteen scientists and two laymen who made important contributions to the knowledge and treatment of poliomyelitis are honored by the [[Polio Hall of Fame]] at the [[Roosevelt Warm Springs Institute for Rehabilitation]] in [[Warm Springs, Georgia]], USA. |

|||

== See also == |

|||

* [[List of poliomyelitis survivors]] |

|||

== Notes and references == |

|||

<!-- --------------------------------------------------------------- |

|||

See http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wikipedia:Footnotes for a |

|||

discussion of different citation methods and how to generate |

|||

footnotes using the <ref> & </ref> tags and the {{Reflist}} template |

|||

-------------------------------------------------------------------- --> |

|||

{{Reflist|2}} |

|||

== Further reading == |

|||

<div class="references-small" style="-moz-column-count:2; column-count:2;"> |

|||

*{{cite book | author = Frauenthal HWA, Manning JVV | title = Manual of infantile paralysis, with modern methods of treatment: Pathology. | publisher = Davis | location = Philadelphia| year = 1914| url= http://books.google.com/books?vid=029ZCFMPZ0giNI1KiG6E&id=piyLQnuT-1YC&printsec=titlepage | pages = pp. 79–101 | oclc = 2078290}} (Full text available from [[Google Books]], with hundreds of pictures.) |

|||

* {{cite book |author = Huckstep RL |title=Poliomyelitis — a guide for developing countries including appliances and rehabilitation for the disabled |url= http://www.worldortho.com/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=522&Itemid=267 |publisher=Churchill Livingstone |location=Edinburgh |year=1975 |pages= |isbn=0443013128 |oclc= |doi=}} (A look at the modern polio patient and polio treatment techniques.) |

|||

*{{cite book|author = Kluger Jefferey|title=Splendid Solution - Jonas Salk and the Conquest of Polio |url= http://www.amazon.com/Splendid-Solution-Jonas-Conquest-Polio/dp/0425205703/ref=pd_bbs_sr_1?ie=UTF8&s=books&qid=1219368729&sr=8-1|publisher=G. P. Putnam's Sons|location=New York |year=2004 |pages=319 |isbn=039915216 |oclc=|doi=}} (A social history of the effects of Polio on early twentieth century America and the search for a vaccine.) |

|||

*Try the [http://americanhistory.si.edu/polio/ Whatever Happened to Polio?] Smithsonian Institution National Museum of American History online interactive exhibit. The exhibit is now on permanent display at the [http://www.rooseveltrehab.org/ Roosevelt Warm Springs Institute for Rehabilitation] in Georgia, USA<ref>[http://www.rotary.org/en/ServiceAndFellowship/Polio/Announcements/Pages/0710_PolioPlusPartner.aspx Rotary International News] Article: Visit the Whatever Happened to Polio Exhibit. 1 October 2007.</ref>. |

|||

</div> |

|||

== External links == |

|||

{{commonscat|Polio}} |

|||

{{wiktionary}} |

|||

* {{dmoz|Health/Conditions_and_Diseases/Infectious_Diseases/Viral/Poliomyelitis/}} |

|||

* [http://www.scq.ubc.ca/polio.pdf Polio: A Virus' Struggle] (PDF format), a comic [[graphic novella]] |

|||

* [http://www.paho.org/English/DPI/Number2_article8.htm Fermín: Making Polio History], the last case of polio reported in the Americas |

|||

* [http://www.johnprestwich.btinternet.co.uk/40-years-a-layabout.htm John Prestwich – 40 years a layabout], a UK polio survivor who lives in an iron lung |

|||

{{-}} |

|||

{{Viral diseases}} |

|||

{{Featured article}} |

|||

[[Category:Poliomyelitis| ]] |

|||

<!-- interwiki --> |

|||

[[ar:شلل أطفال]] |

|||

[[bs:Dječija paraliza]] |

|||

[[ca:Poliomielitis]] |

|||

[[cs:Dětská obrna]] |

|||

[[cy:Poliomyelitis]] |

|||

[[da:Polio]] |

|||

[[de:Poliomyelitis]] |

|||

[[es:Poliomielitis]] |

|||

[[eo:Poliomjelito]] |

|||

[[fr:Poliomyélite]] |

|||

[[gl:Poliomielite]] |

|||

[[ko:소아마비]] |

|||

[[hr:Dječja paraliza]] |

|||

[[io:Poliomielito]] |

|||

[[id:Poliomielitis]] |

|||

[[is:Mænusótt]] |

|||

[[it:Poliomielite]] |

|||

[[he:שיתוק ילדים]] |

|||

[[lv:Poliomielīts]] |

|||

[[lt:Poliomielitas]] |

|||

[[nl:Poliomyelitis]] |

|||

[[ja:急性灰白髄炎]] |

|||

[[no:Poliomyelitt]] |

|||

[[nn:Poliomyelitt]] |

|||

[[pl:Choroba Heinego-Medina]] |

|||

[[pt:Poliomielite]] |

|||

[[ru:Полиомиелит]] |

|||

[[simple:Poliomyelitis]] |

|||

[[sk:Detská obrna]] |

|||

[[su:Polio]] |

|||

[[fi:Polio]] |

|||

[[sv:Polio]] |

|||

[[te:పోలియో]] |

|||

[[vi:Bệnh viêm tủy xám]] |

|||

[[tr:Çocuk felci]] |

|||

[[uk:Поліомієліт]] |

|||

[[zh:脊髓灰質炎]] |

|||

Revision as of 00:48, 14 October 2008

| Polio | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Infectious diseases, neurology, orthopedic surgery |

Poliomyelitis, often called polio or infantile paralysis, is an acute viral infectious disease spread from person to person, primarily via the fecal-oral route.[1] The term derives from the Greek polio (πολίός), meaning "grey", myelon (µυελός), referring to the "spinal cord", and -itis, which denotes inflammation.[2] Although around 90% of polio infections cause no symptoms at all, affected individuals can exhibit a range of symptoms if the virus enters the blood stream.[3] In fewer than 1% of cases the virus enters the central nervous system, preferentially infecting and destroying motor neurons, leading to muscle weakness and acute flaccid paralysis. Different types of paralysis may occur, depending on the nerves involved. Spinal polio is the most common form, characterized by asymmetric paralysis that most often involves the legs. Bulbar polio leads to weakness of muscles innervated by cranial nerves. Bulbospinal polio is a combination of bulbar and spinal paralysis.[4]

Poliomyelitis was first recognized as a distinct condition by Jakob Heine in 1840.[5] Its causative agent, poliovirus, was identified in 1908 by Karl Landsteiner.[5] Although major polio epidemics were unknown before the late 19th century, polio was one of the most dreaded childhood diseases of the 20th century. Polio epidemics have crippled thousands of people, mostly young children; the disease has caused paralysis and death for much of human history. Polio had existed for thousands of years quietly as an endemic pathogen until the 1880s, when major epidemics began to occur in Europe; soon after, widespread epidemics appeared in the United States.[6] By 1910, much of the world experienced a dramatic increase in polio cases and frequent epidemics became regular events, primarily in cities during the summer months. These epidemics—which left thousands of children and adults paralyzed—provided the impetus for a "Great Race" towards the development of a vaccine. The polio vaccines developed by Jonas Salk in 1952 and Albert Sabin in 1962 are credited with reducing the global number of polio cases per year from many hundreds of thousands to around a thousand.[7] Enhanced vaccination efforts led by the World Health Organization, UNICEF and Rotary International could result in global eradication of the disease.[8] Yes, Eleni, you do have polio. <-- see we got to the point.

Cause

Poliomyelitis is caused by infection with a member of the genus Enterovirus known as poliovirus (PV). This group of RNA viruses prefers to inhabit the gastrointestinal tract.[1] PV infects and causes disease in humans alone.[3] Its structure is very simple, composed of a single (+) sense RNA genome enclosed in a protein shell called a capsid.[3] In addition to protecting the virus’s genetic material, the capsid proteins enable poliovirus to infect certain types of cells. Three serotypes of poliovirus have been identified—poliovirus type 1 (PV1), type 2 (PV2), and type 3 (PV3)—each with a slightly different capsid protein.[9] All three are extremely virulent and produce the same disease symptoms.[3] PV1 is the most commonly encountered form, and the one most closely associated with paralysis.[10]

Individuals who are exposed to the virus, either through infection or by immunization with polio vaccine, develop immunity. In immune individuals, IgA antibodies against poliovirus are present in the tonsils and gastrointestinal tract and are able to block virus replication; IgG and IgM antibodies against PV can prevent the spread of the virus to motor neurons of the central nervous system.[11] Infection or vaccination with one serotype of poliovirus does not provide immunity against the other serotypes, and full immunity requires exposure to each serotype.[11]

Transmission

Poliomyelitis is highly contagious and spreads easily from human-to-human contact.[11] In endemic areas, wild polioviruses can infect virtually the entire human population.[12] It is seasonal in temperate climates, with peak transmission occurring in summer and autumn.[11] These seasonal differences are far less pronounced in tropical areas.[12] The time between first exposure and first symptoms, known as the incubation period, is usually 6 to 20 days, with a maximum range of 3 to 35 days.[13] Virus particles are excreted in the feces for several weeks following initial infection.[13] The disease is transmitted primarily via the fecal-oral route, by ingesting contaminated food or water. It is occasionally transmitted via the oral-oral route,[10] a mode especially visible in areas with good sanitation and hygiene.[11] Polio is most infectious between 7–10 days before and 7–10 days after the appearance of symptoms, but transmission is possible as long as the virus remains in the saliva or feces.[10]

Factors that increase the risk of polio infection or affect the severity of the disease include immune deficiency,[14] malnutrition,[15] tonsillectomy,[16] physical activity immediately following the onset of paralysis,[17] skeletal muscle injury due to injection of vaccines or therapeutic agents,[18] and pregnancy.[19] Although the virus can cross the placenta during pregnancy, the fetus does not appear to be affected by either maternal infection or polio vaccination.[20] Maternal antibodies also cross the placenta, providing passive immunity that protects the infant from polio infection during the first few months of life.[21]

Classification

| Outcome | Proportion of cases[4] |

|---|---|

| Asymptomatic | 90–95% |

| Minor illness | 4–8% |

| Non-paralytic aseptic meningitis |

1–2% |

| Paralytic poliomyelitis | 0.1–0.5% |

| — Spinal polio | 79% of paralytic cases |

| — Bulbospinal polio | 19% of paralytic cases |

| — Bulbar polio | 2% of paralytic cases |

The term poliomyelitis is used to identify the disease caused by any of the three serotypes of poliovirus. Two basic patterns of polio infection are described: a minor illness which does not involve the central nervous system (CNS), sometimes called abortive poliomyelitis, and a major illness involving the CNS, which may be paralytic or non-paralytic.[22] In most people with a normal immune system, a poliovirus infection is asymptomatic. Rarely the infection produces minor symptoms; these may include upper respiratory tract infection (sore throat and fever), gastrointestinal disturbances (nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, constipation or, rarely, diarrhea), and influenza-like illnesses.[4]

The virus enters the central nervous system in about 3% of infections. Most patients with CNS involvement develop non-paralytic aseptic meningitis, with symptoms of headache, neck, back, abdominal and extremity pain, fever, vomiting, lethargy and irritability.[2][23] Approximately 1 in 200 to 1 in 1000 cases progress to paralytic disease, in which the muscles become weak, floppy and poorly-controlled, and finally completely paralyzed; this condition is known as acute flaccid paralysis.[24] Depending on the site of paralysis, paralytic poliomyelitis is classified as spinal, bulbar, or bulbospinal. Encephalitis, an infection of the brain tissue itself, can occur in rare cases and is usually restricted to infants. It is characterized by confusion, changes in mental status, headaches, fever, and less commonly seizures and spastic paralysis.[25]

Pathophysiology