Last Supper: Difference between revisions

Revert |

Daniel9247 (talk | contribs) →Theology of the Last Supper: Restored missing image of the previous version of the image. Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|Meal that Jesus shared with his apostles before his crucifixion}} |

|||

:''This article relates to the event described in the [[New Testament]] of the [[Bible]], see [[The Last Supper (disambiguation)]] for other uses, including a list of famous works of art with this name. |

|||

{{Other uses|The Last Supper (disambiguation)}} |

|||

{{Use dmy dates|date=April 2021}} |

|||

<imagemap> |

|||

Image:The Last Supper - Leonardo Da Vinci - High Resolution 32x16.jpg|thumb|400px|alt=''The Last Supper'' by Leonardo da Vinci - Clickable Image|Depictions of the [[Last Supper in Christian art]] have been undertaken by artistic masters for centuries, [[Leonardo da Vinci]]'s [[The Last Supper (Leonardo)|late-1490s mural painting]] in [[Milan]], Italy, being the best-known example.{{sfn|Zuffi|2003|pp=254–259}} <small>''(Clickable image—use cursor to identify.)''</small> |

|||

poly 550 2550 750 2400 1150 2300 1150 2150 1200 2075 1500 2125 1525 2300 1350 2800 1450 3000 1700 3300 1300 3475 650 3500 550 3300 450 3000 [[Bartholomew the Apostle|Bartholomew]] |

|||

[[Image:Leonardo_da_Vinci_%281452-1519%29_-_The_Last_Supper_%281495-1498%29.jpg|thumb|right|280px|''[[The Last Supper (Leonardo)|The Last Supper]]'' in Milan (1498), by [[Leonardo da Vinci]]]] |

|||

poly 1575 2300 1625 2150 1900 2150 1925 2500 1875 2600 1800 2750 1600 3250 1425 3100 1400 2800 1375 2600 [[James, son of Alphaeus|James Minor]] |

|||

poly 1960 2150 2200 2150 2350 2500 2450 2575 2375 2725 2375 2900 2225 3100 2225 3225 1600 3225 1825 2700 1975 2450 1925 2300 [[Saint Andrew|Andrew]] |

|||

poly 2450 2575 2775 2500 2700 2650 2800 2700 2600 3000 2600 3250 2300 3250 2200 3200 2300 3000 [[Saint Peter|Peter]] |

|||

poly 2750 2500 2950 2400 3125 2600 3175 2700 3300 2850 3700 3200 3750 3200 3650 3350 3400 3200 3000 3350 2600 3325 2750 2800 2900 2700 2700 2650 [[Judas Iscariot|Judas]] |

|||

poly 3000 2350 3300 2350 3350 2660 3560 2600 3565 2690 3250 2800 3125 2575 [[Saint Peter|Peter]] |

|||

poly 3332 2338 3528 2240 4284 3024 4074 3332 3864 3290 3780 3150 3668 3192 3598 3024 3374 2870 3388 2772 3542 2800 3668 2702 3542 2590 3430 2604 3350 2600 3300 2500[[John the Apostle|John]] |

|||

poly 4775 2184 4915 2128 5055 2212 5083 2352 5111 2464 5181 2604 5307 2744 5573 3052 5615 3192 5657 3290 5573 3402 5461 3332 5335 3248 4495 3248 4439 3388 4243 3388 4075 3360 4173 3136 4327 3010 4509 2730 4663 2520 4733 2394 [[Jesus]] |

|||

poly 5900 2100 5900 2150 5800 2400 5800 2500 5675 2589 5480 2671 5438 2507 5425 2301 5589 2452 5630 2301 5650 2100 [[Thomas the Apostle|Thomas]] |

|||

poly 5918 2150 6041 2109 6137 2246 6192 2411 6110 2589 6110 2726 6192 2822 6302 2740 6589 3109 5658 3178 5575 2918 5300 2698 5233 2589 5274 2438 5370 2507 5521 2685 5617 2671 5712 2575 5822 2507 5808 2287 5822 2175 [[James, son of Zebedee|James Greater]] |

|||

poly 6137 2013 6439 2013 6863 2260 7110 2515 6726 2675 6507 2548 6425 2630 6356 2753 6548 2849 6699 2781 7082 2794 7178 3109 6699 3178 6548 2986 6397 2835 6165 2775 6110 2589 6233 2438 6302 2383 6151 2287 6096 2164 [[Philip the Apostle|Philip]] |

|||

poly 7635 2123 7800 2013 8000 2055 8025 2287 7950 2438 8000 2698 8055 2918 7959 3164 7233 3164 7124 2972 7124 2794 6548 2794 6384 2781 6384 2671 6493 2575 6750 2650 7075 2550 7219 2400 7625 2300 [[Matthew the Apostle|Matthew]] |

|||

poly 8325 2096 8600 2109 8635 2493 8615 2726 8439 2781 8274 2740 8125 2835 8151 2931 8400 2975 8411 3068 8589 3041 8617 3205 7987 3260 8124 3027 7987 2644 7904 2493 7959 2425 8096 2356 [[Judas Thaddaeus|Jude]] |

|||

poly 8800 2150 8900 2125 9055 2150 9125 2397 9400 2475 9550 2931 9625 3301 9151 3397 8535 3219 8726 3014 8466 3068 8411 2918 8178 2931 8124 2835 8329 2753 8535 2794 8726 2603 8725 2342 [[Simon the Zealot|Simon]] |

|||

</imagemap> |

|||

The '''Last Supper''' is the final meal that, in the [[Gospel]] accounts, [[Jesus]] shared with his [[apostles in the New Testament|apostles]] in [[Jerusalem]] before [[Crucifixion of Jesus|his crucifixion]].{{sfn|Cross|Livingstone|2005|p=958|loc=Last Supper}} The Last Supper is commemorated by Christians especially on [[Maundy Thursday|Holy Thursday]].{{sfn|Windsor|Hughes|1990|p=64}} The Last Supper provides the scriptural basis for the [[Eucharist]], also known as "Holy Communion" or "The Lord's Supper".{{sfn|Hazen|2002|p=34}} |

|||

According to the [[Gospel]]s, the '''Last Supper''' (also called '''Lord's Supper''') was the last meal [[Jesus]] shared with his [[Twelve Apostles]] before his death. The Last Supper has been the subject of many paintings, perhaps the most famous by [[The Last Supper (Leonardo)|Leonardo da Vinci]]. In the course of the Last Supper, and with specific reference to taking the bread and the wine, Jesus told his disciples, "Do this in remembrance of Me", ([[1 Corinthians]] 11:23-25). (The vessel which was used to serve the wine, the [[Holy Chalice]], is considered by some to be the "[[Holy Grail]]"). Many Christians describe this as the institution of the [[Eucharist]]. |

|||

The [[First Epistle to the Corinthians]] contains the earliest known mention of the Last Supper. The four [[canonical gospel]]s state that the Last Supper took place in the week of [[Passover]], days after Jesus's [[triumphal entry into Jerusalem]], and before Jesus was crucified on [[Good Friday]].{{sfn|Evans|2003|pp=465–477}}{{sfn|Fahlbusch|2005|pp=52–56}} During the meal, [[Jesus predicts his betrayal]] by one of the apostles present, and foretells that before the next morning, [[Apostle Peter|Peter]] will thrice [[Denial of Peter|deny knowing him]].{{sfn|Evans|2003|pp=465–477}}{{sfn|Fahlbusch|2005|pp=52–56}} |

|||

According to tradition, the Last Supper took place in what is called today The [[Room of the Last Supper]] on [[Mount Zion]], just outside of the walls of the [[Old City]] of [[Jerusalem]]. |

|||

The three [[Synoptic Gospel]]s and the First Epistle to the Corinthians include the account of the institution of the Eucharist in which Jesus takes bread, breaks it and gives it to those present, saying "This is my body given to you".{{sfn|Evans|2003|pp=465–477}}{{sfn|Fahlbusch|2005|pp=52–56}} The Gospel of John tells of Jesus [[Maundy (foot washing)|washing the feet of the apostles]],<ref>{{bibleverse|John|13:1–15}}</ref> giving [[New Commandment|the new commandment]] "to love one another as I have loved you",<ref>{{bibleverse|John|13:33–35}}</ref> and has a detailed [[Farewell Discourse|farewell discourse]] by Jesus, calling the apostles who follow his teachings "friends and not servants", as he prepares them for his departure.<ref>{{bibleverse|John|14–17}}</ref>{{sfn|Cross|Livingstone|2005|p=570|loc=Eucharist}}{{sfn|Kruse|2004|p=103}} |

|||

==In the New Testament== |

|||

===Chronology=== |

|||

The meal is considered to be by most scholars likely to have been a [[Passover Seder]], celebrated on the Thursday night ([[Holy Thursday]]) before Jesus was [[crucifixion|crucified]] on Friday ([[Good Friday]]). This belief is based on the chronology of the [[Synoptic Gospels]], but the chronology in the [[Gospel of John]] is regarded by many as placing the Last Supper on the evening before the Passover (John 13:1, 18:28). References in John's Gospel to the Day of Preparation of the Passover (John 19:14, 31, and 42), are also taken by many to indicate that Christ's death occurred at the time of the slaughter of the Passover lambs (this latter chronology is the one accepted by the [[Eastern Orthodoxy|Orthodox Church]]). However, those that place the Last Supper during a Thursday evening [[Passover Seder]] generally regard Mark 14:12 and Luke 22:7 as the only explicit references in the [[Gospels]] to the slaying of Passover lambs at the time of Christ's [[crucifixion]], and take the Day of Preparation in the [[Gospel of John]] as a likely reference to the Passover Friday during which preparations were made for the weekly [[Sabbath]] rest. Additionally, several scholars have questioned these chronologies, and have rejected the assumption that the synoptics refer to the Passover Seder and held that they are harmonious with John.<ref name="morris">See [[Leon Morris]], ''The Gospel According to John, Revised'', pp. 684-695.</ref> Some Christians believe that a thorough examination of the Gospels indicates that the Last Supper was on a Tuesday, and that Jesus was [[crucifixion|crucified]] on a Wednesday.<ref name="Day"><cite>[http://www.geocities.com/bc1in2k/Death_Res_JC.html When Christ Died, and Rose]</cite></ref> |

|||

Some scholars have looked to the Last Supper as the source of early Christian Eucharistic traditions.{{sfn|Bromiley|1979|p=164}}{{sfn|Wainwright|Tucker|2006|p=}}{{Sfn|Marshall|2006|p=33}}{{Sfn|Jeremias|1966|p=51–62}}{{Sfn|Meier|1991|pp=302–309}}{{Sfn|Pitre|2011}} Others see the account of the Last Supper as derived from 1st-century eucharistic practice as described by Paul in the mid-50s.{{sfn|Wainwright|Tucker|2006|p=}}{{sfn|Funk|1998|pp=1–40|loc=Intruduction}}{{Sfn|Bultmann|1963}}{{Sfn|Bultmann|1958}} |

|||

[[Image:Lastsupperqormi.JPG|thumb|left|Statue of The Last Supper, used during the [[Good Friday]] procession in [[Qormi]], [[Malta]]]] |

|||

The meal is discussed at length in all four [[Gospels]] of the [[Biblical canon|canonical Bible]]. The [[Synoptic Gospels]] state that it was the [[seder]] for the [[Passover]], and are interpreted by some scholars to state that in the morning of the same day the [[Paschal lamb]], for the meal, had been [[sacrifice]]d. However, under the [[Judaism|Jewish]] method of reckoning time, the day was considered to begin straight after [[dusk]], and so the Passover feast would be regarded as occurring on the day ''after'' the lamb was sacrificed. This implies that either the synoptics are not written with an awareness of the Jewish method of time reckoning (Kilgallen 264), or that they used the literary technique of telescoping events that actually happened on different days into just happening on single ones (Brown et al. 625). Others interpret the language of the Synoptic Gospels as sufficiently broad to allow for an evening sacrifice of the Passover lambs. |

|||

==Terminology== |

|||

By contrast, in the [[chronology]] of the [[Gospel of John]], the meal is stated to have occurred ''before'' the Passover, and ''before'' the Paschal lamb has been slaughtered, according to some interpreters, and consequently implying that Jesus himself died at the time when the Paschal lamb was due to be slaughtered. Almost all scholars view John's Gospel as later than the others, and most scholars see it as at least partly dependent on the Synoptics, and consequently some view John's chronology as highly contrived. Nevertheless, in [[Eastern Orthodoxy]] it is the chronology of John that is used in the traditional celebration of [[Easter]], and similarly some have argued that a thorough examination of the Gospels indicates that the Last Supper was on a Tuesday, rather than a Thursday. |

|||

[[File:Last Supper.jpg|thumb|Last Supper, [[Monreale Cathedral mosaics]] ([[Palermo]], [[Sicily]], Italy)]] |

|||

The term "Last Supper" does not appear in the [[New Testament]],{{sfn | Armentrout | Slocum | 1999 | p=292}}{{sfn | Fitzmyer | 1981 | p=1378}} but traditionally many Christians refer to such an event.{{sfn | Fitzmyer | 1981 | p=1378}} The term "Lord's Supper" refers both to the biblical event and the act of "Holy Communion" and [[Eucharist]]ic ("thanksgiving") celebration within their [[liturgy]]. [[Evangelicals|Evangelical Protestants]] also use the term "Lord's Supper", but most do not use the terms "Eucharist" or the word "Holy" with the name "Communion".{{sfn | Thompson | 1996 | pp=493–494}} |

|||

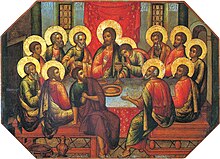

The [[Eastern Orthodox]] use the term "Mystical Supper" which refers both to the biblical event and the act of Eucharistic celebration within liturgy.{{sfn | McGuckin | 2010 | pp=293, 297}} The [[Russian Orthodox]] also use the term "Secret Supper" ({{lang-chu|"Тайная вечеря"}}, ''Taynaya vecherya''). |

|||

===Location=== |

|||

==Scriptural basis== |

|||

According to tradition, the Last Supper took place in what is called today The [[Room of the Last Supper]] on [[Mount Zion]], just outside of the walls of the [[Old City]] of [[Jerusalem]], and is traditionally known as ''The Upper Room''. This is based on the account in the synoptics that states that Jesus had instructed a pair of unnamed disciples to go to ''the city'' to meet a ''man carrying a jar of water'', who would lead them to a house, where they were to ask for the room where ''the teacher'' has a guest room. This room is specified as being the upper room, and they ''prepare the passover'' there. |

|||

The last meal that Jesus shared with his apostles is described in all four [[canonical Gospel]]s<ref>{{Bibleref2|Mt.|26:17–30}}, {{Bibleref2|Mk.|14:12–26}}, {{Bibleref2|Lk.|22:7–39}} and {{Bibleref2|Jn.|13:1–17:26}}</ref> as having taken place in the week of the [[Passover]]. This meal later became known as the Last Supper.{{sfn|Fahlbusch|2005|pp=52–56}} The Last Supper was likely a retelling of the events of the last meal of Jesus among the [[History of Christianity|early Christian community]], and became a ritual which recounted that meal.{{sfn | Harrington | 2001 | p=49}} |

|||

Paul's [[First Epistle to the Corinthians]],<ref>{{bibleverse|1cor|11:23–26||11:23–26}}</ref> which was likely written before the Gospels, includes a reference to the Last Supper but emphasizes the theological basis rather than giving a detailed description of the event or its background.{{sfn|Evans|2003|pp=465–477}}{{sfn|Fahlbusch|2005|pp=52–56}} |

|||

It is not actually specified where ''the city'' refers to, and it may refer to one of the [[suburb]]s of Jerusalem, such as Bethany; the traditional location is not based on anything more specific in the Bible, and may easily be wrong. The traditional location is an area that, according to [[archaeology]], had a large [[Essenes|Essene]] community, adding to the points which make several scholars suspect a link between Jesus and the group (Kilgallen 265). |

|||

=== |

===Background and setting=== |

||

[[ |

[[File:Dieric Bouts - The Last Supper - WGA03003.jpg|thumb|right|[[Altarpiece of the Holy Sacrament|''The Last Supper'']] by [[Dieric Bouts]], 1464–1468]] |

||

The overall narrative that is shared in all Gospel accounts that leads to the Last Supper is that after the [[triumphal entry into Jerusalem]] early in the week, and encounters with various people and the Jewish elders, Jesus and his disciples share a meal towards the end of the week. After the meal, Jesus is betrayed, arrested, tried, and then [[Crucifixion of Jesus|crucified]].{{sfn|Evans|2003|pp=465–477}}{{sfn|Fahlbusch|2005|pp=52–56}} |

|||

Key events in the meal are the preparation of the disciples for the departure of Jesus, the predictions about the impending betrayal of Jesus, and the foretelling of the upcoming denial of Jesus by [[Apostle Peter]].{{sfn|Evans|2003|pp=465–477}}{{sfn|Fahlbusch|2005|pp=52–56}} |

|||

In the course of the Last Supper, according to the synoptics (but not John), Jesus divides up some bread, says [[grace]], and hands the pieces to his disciples, saying ''this is my body''. He then takes a cup of [[wine]], says grace, and hands it around, saying ''this is my blood of the 'covenant', which is poured for many ''. Finally he tells the disciples ''do this in remembrance of me''. |

|||

===Prediction of Judas' betrayal=== |

|||

{{Main|Jesus predicts his betrayal}} |

|||

In Matthew 26:24–25, Mark 14:18–21, Luke 22:21–23 and John 13:21–30, during the meal, Jesus predicted that one of the apostles present would betray him.{{sfn | Cox |Easley| 2007 | p=182}}<ref>{{Bibleref2|Matthew|26:24–25}}, {{Bibleref2|Mark|14:18–21}}, {{Bibleref2|Luke|22:21–23}} and {{Bibleref2|John|13:21–30}}</ref> Jesus is described as reiterating, despite each apostle's assertion that he would not betray Jesus, that the betrayer would be one of those who were present, and saying that there would be "woe to the man who betrays the [[Son of man (Christianity)|Son of man]]! It would be better for him if he had not been born."<ref>{{bibleverse|Mark|14:20–21}}</ref> |

|||

In Matthew 26:23–25 and John 13:26–27, [[Judas Iscariot|Judas]] is specifically identified as the traitor.<ref>{{Bibleref2|Matthew|26:23–25}} and {{Bibleref2|John|13:26–27}}</ref> In the Gospel of John, when asked about the traitor, Jesus states: |

|||

During Jewish Passover meals, the wine was usually consumed during the eating of the bread, but here it occurs after. This may indicate that the event was not the official Passover dinner, and hence more in line with John's chronology (Brown et al. 626), although the meal could easily have been altered during the Last Supper for symbolic/religious purposes, or simply because the Gospel writers did not have complete knowledge of Jewish practice, as suggested by their chronologies. |

|||

{{Blockquote|"It is the one to whom I will give this piece of bread when I have dipped it in the dish." Then, dipping the piece of bread, he gave it to Judas, the son of Simon Iscariot. As soon as Judas took the bread, Satan entered into him.|source={{harvnb|Evans|2003|pp=465–477}} {{harvnb|Fahlbusch|2005|pp=52–56}} }} |

|||

This institute has been regarded by Christians of different denominations as the first [[Eucharist]] or [[Holy Communion]]. |

|||

===Institution of the Eucharist=== |

|||

Jesus' behaviour may be derived from a passage in the [[Book of Isaiah]], where {{bibleref|Isaiah|53:12}} refers to a blood sacrifice that [[Moses]] is described in [[Exodus]] as having made in order to seal a covenant with God {{bibleref|Exodus|24:8}}. Scholars often interpret the description of Jesus' behaviour as him asking his disciples to consider themselves part of a sacrifice, where Jesus is the one due to physically undergo it (Brown et al. 626). |

|||

{{Main|Origin of the Eucharist}} |

|||

{{Death of Jesus|expanded=Passion}} |

|||

The three Synoptic Gospel accounts describe the Last Supper as a Passover meal,<ref name="Sherman">{{cite book |last1=Sherman |first1=Robert J. |title=King, Priest, and Prophet: A Trinitarian Theology of Atonement |date=2 March 2004 |publisher=A&C Black |isbn=978-0-567-02560-9 |page=176 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=0efTAwAAQBAJ&dq=The+three+Synoptic+Gospel+accounts+describe+the+Last+Supper+as+a+Passover+meal,&pg=PA176 |access-date=1 August 2022 |language=en}}</ref><ref name="Saulnier">{{cite book |last1=Saulnier |first1=Stéphane |title=Calendrical Variations in Second Temple Judaism: New Perspectives on the 'Date of the Last Supper' Debate |date=3 May 2012 |publisher=BRILL |isbn=978-90-04-16963-0 |page=3 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=0eR2z_4JngcC&dq=The+three+Synoptic+Gospel+accounts+describe+the+Last+Supper+as+a+Passover+meal,&pg=PA3 |access-date=1 August 2022 |language=en}}</ref> disagreeing with John.<ref name="Saulnier"/> Each gives somewhat different versions of the order of the meal. In chapter 26 of the Gospel of Matthew, Jesus prays thanks for the bread, divides it, and hands the pieces of bread to his disciples, saying "Take, eat, this is my body." Later in the meal Jesus takes a cup of wine, offers another [[prayer]], and gives it to those present, saying "Drink from it, all of you; for this is my blood of the covenant, which is poured out for many for the forgiveness of sins. I tell you, I will never again drink of this fruit of the vine until that day when I drink it new with you in my Father's kingdom." |

|||

In chapter 22 of the Gospel of Luke, however, the wine is blessed and distributed before the bread, followed by the bread, then by a second, larger cup of wine, as well as somewhat different wordings. Additionally, according to Paul and Luke, he tells the disciples "do this in remembrance of me." This event has been regarded by Christians of most denominations as the institution of the Eucharist. There is recorded celebration of the Eucharist by the early Christian community [[Jerusalem in Christianity|in Jerusalem]].{{sfn|Cross|Livingstone|2005|p=570|loc=Eucharist}} |

|||

===Betrayal=== |

|||

The institution of the Eucharist is recorded in the three Synoptic Gospels and in Paul's [[First Epistle to the Corinthians]]. As noted above, Jesus's words differ slightly in each account. In addition, Luke 22:19b–20 is a disputed text which does not appear in some of the early manuscripts of Luke.<ref>{{Bibleref2|Luke|22:19b–20}}</ref> Some scholars, therefore, believe that it is an [[Interpolation (manuscripts)|interpolation]], while others have argued that it is original.{{sfn|Marshall|Millard|Packer|Wiseman|1996|p= 697}}{{sfn | Blomberg | 2009 | p=333}} |

|||

According to the Canonical Gospels, during the meal Jesus revealed that one of [[Twelve Apostles|his Apostles]] would betray him. Despite the assertions of each Apostle that it would not be he, Jesus is described as reiterating that it would be one of those who were present, and goes on to say that there shall be ''woe to the man who betrays the [[Son of Man]]! It would be better for him if he had not been born'' ({{bibleref|Mark|14:20-21}}). |

|||

A comparison of the accounts given in the Gospels and 1 Corinthians is shown in the table below, with text from the [[American Standard Version|ASV]]. The disputed text from Luke 22:19b–20 is in {{em|italics}}. |

|||

As cited above, the [[Gospel of Mark]] does not specifically identify the betrayer. The same is true in the [[Gospel of Luke]] which is limited to asserting that the betrayer was present at the table with Jesus ({{bibleref|Luke|22:21}}). It is only in the [[Gospel of Matthew]] ({{bibleref|Matthew|26:23-26:25}}) and [[The Gospel of John]] ({{bibleref|John|13:26-13:27}}) where [[Judas Iscariot]] is specifically singled out. This is the very moment poignantly portrayed in [[Leonardo da Vinci]]'s [[The Last Supper (Leonardo)|The Last Supper]]. |

|||

{| class="wikitable" |

|||

|- |

|||

! <small>Mark 14:22–24</small> |

|||

| And as they were eating, he took bread, and when he had blessed, he brake it, and gave to them, and said, Take ye: this is my body. |

|||

| And he took a cup, and when he had given thanks, he gave to them: and they all drank of it. And he said unto them, 'This is my blood of the covenant, which is poured out for many.'<ref>{{Bibleref2|Mark|14:22–24|ASV}}</ref> |

|||

|- |

|||

! <small>Matthew 26:26–28</small> |

|||

| And as they were eating, Jesus took bread, and blessed, and brake it; and he gave to the disciples, and said, 'Take, eat; this is my body.' |

|||

| And he took a cup, and gave thanks, and gave to them, saying, 'Drink ye all of it; for this is my blood of the covenant, which is poured out for many unto remission of sins.'<ref>{{Bibleref2|Matthew|26:26–28|ASV}}</ref> |

|||

|- |

|||

! <small>1 Corinthians 11:23–25</small> |

|||

| For I received of the Lord that which also I delivered unto you, that the Lord Jesus in the night in which he was betrayed took bread; and when he had given thanks, he brake it, and said, 'This is my body, which is for you: this do in remembrance of me.'<ref>{{Bibleref2|1Cor|11:23|ASV|1 Corinthians 11:23–25}}</ref> |

|||

| In like manner also the cup, after supper, saying, 'This cup is the new covenant in my blood: this do, as often as ye drink it, in remembrance of me.' |

|||

|- |

|||

! <small>Luke 22:19–20</small> |

|||

| And he took bread, and when he had given thanks, he brake it, and gave to them, saying, 'This is my body {{em|which is given for you: this do in remembrance of me.'}}<ref>{{Bibleref2|Luke|22:19–20|ASV}}</ref> |

|||

| {{em|And the cup in like manner after supper, saying, 'This cup is the new covenant in my blood, even that which is poured out for you.'}} |

|||

|} |

|||

[[File:The Last Supper (1886), by Fritz von Uhde.jpg|thumb|''The Last Supper'' by [[Fritz von Uhde]] (1886)]] |

|||

===Abandonment=== |

|||

Jesus' actions in sharing the bread and wine have been linked with Isaiah 53:12<ref>{{Bibleref2|Isaiah|53:12}}</ref> which refers to a blood sacrifice that, as recounted in Exodus 24:8,<ref>{{Bibleref2|Exodus|24:8}}</ref> [[Moses]] offered in order to seal a covenant with God. Some scholars interpret the description of Jesus' action as asking his disciples to consider themselves part of a sacrifice, where Jesus is the one due to physically undergo it.<ref name=Brown /> |

|||

As well as the prediction of betrayal, the four canonical gospels recount that Jesus knew the Apostles(desciples) would ''fall away''. [Simon Peter] states that he will not abandon Jesus even if the others do, but Jesus tells him that Simon would deny Jesus thrice before the [[rooster|cock]] had crowed twice. Peter is described as continuing to deny it, stating that he would remain true even if it meant death, and the other apostles are described as stating the same about themselves. |

|||

Although the Gospel of John does not include a description of the bread and wine ritual during the Last Supper, most scholars agree that John 6:58–59<ref>{{Bibleref2|John|6:58–59}}</ref> (the [[Bread of Life Discourse]]) has a Eucharistic nature and resonates with the "[[words of institution]]" used in the Synoptic Gospels and the Pauline writings on the Last Supper.{{sfn | Freedman | 2000 | p=792}} |

|||

===The sermon=== |

|||

===Prediction of Peter's denial=== |

|||

After the meal, according to John (but not mentioned at all by the Synoptics), Jesus gave a large sermon to the disciples. The sermon is sometimes referred to as the '''farewell discourse''' of Jesus, and has historically been considered a source of Christian teaching, particularly on the subject of [[Christology]]. Amongst the Canonical Gospels John is unusual in the complexity of its Christology (which has led to [[authorship of John|questions about its authenticity]]), and this sermon portrays one of the most complex Christological descriptions in John. |

|||

{{Main|Denial of Peter}} |

|||

In Matthew 26:33–35, Mark 14:29–31, Luke 22:33–34 and John 13:36–8, Jesus predicts that Peter will deny knowledge of him, stating that [[Denial of Peter|Peter will disown him]] three times before the [[rooster]] crows the next morning.<ref>{{Bibleref2|Matthew|26:33–35}}, {{Bibleref2|Mark|14:29–31}}, {{Bibleref2|Luke|22:33–34}} and {{Bibleref2|John|13:36–8}}</ref> The three [[Synoptic Gospel]]s mention that after the [[arrest of Jesus]], Peter denied knowing him three times, but after the third denial, heard the rooster crow and recalled the prediction as Jesus turned to look at him. Peter then began to cry bitterly.{{sfn | Perkins | 2000 | p=85}}{{sfn|Lange|1865|p=499}} |

|||

===Elements unique to the Gospel of John=== |

|||

Although ostensibly addressing his disciples, most scholars conclude the chapter is written with events concerning the later church in mind, particularly that of the 2nd century. Jesus is presented as explaining the relationship between himself and his followers, and seeking to model this relationship on his own relationship with God. |

|||

{{See also|Washing the feet of the Apostles|The New Commandment|Farewell discourse}} |

|||

[[File:Christ Taking Leave of the Apostles.jpg|thumb|left|Jesus giving the ''[[Farewell Discourse]]'' to his eleven remaining disciples, from the ''[[Maestà (Duccio)|Maesta]]'' by [[Duccio]], 1308–1311]] |

|||

[[John 13]] includes the account of the [[washing the feet of the Apostles]] by Jesus before the meal.{{sfn|Harris|1985|pp=302-311}} In this episode, Apostle Peter objects and does not want to allow Jesus to wash his feet, but Jesus answers him, "Unless I wash you, you have no part with me",<ref>{{bibleverse|Jn|13:8}}</ref> after which Peter agrees. |

|||

In the Gospel of John, after the departure of [[Judas iscariot|Judas]] from the Last Supper, Jesus tells his remaining disciples <ref>{{bibleverse|John|13:33}}</ref> that he will be with them for only a short time, then gives them a [[The New Commandment|New Commandment]], stating:{{sfn | Köstenberger| 2002 | pp=149-151}}{{sfn | Yarbrough | 2008 | p=215}} "A new command I give you: Love one another. As I have loved you, so you must love one another. By this everyone will know that you are my disciples if you love one another."<ref>{{Bibleref2|John|13:34–35}}</ref> Two similar statements also appear later in John 15:12: "My command is this: Love each other as I have loved you",<ref>{{Bibleref2|John|15:12}}</ref> and John 15:17: "This is my command: Love each other."<ref>{{Bibleref2|John|15:17}}</ref>{{sfn | Yarbrough | 2008 | p=215}} |

|||

The chapter introduces the extended [[metaphor]] of [[The Vine|Jesus as the true vine]]. God is described as the vine tender, and his disciples are said to be branches, which must 'abide' in him if they are to 'bear fruit'. The disciples are warned that barren branches are pruned by the vinedresser. This image has been influential in Christian art and iconography. The disciples are reminded of the love of God for Jesus, and of Jesus for the disciples (especially the [[beloved disciple]]), and are then instructed to ''love one another'' in the same manner. It goes on to speak of the ''greatest love'' as being the willingness to ''lay down'' life for one's friends, and this passage has since been widely used to affirm the sacrifice of [[martyr]]s and soldiers in [[war]], and is thus often seen on war memorials and graves. |

|||

At the Last Supper in the Gospel of John, Jesus gives an extended [[sermon]] to his disciples.<ref>{{bibleverse|John|14–16}}</ref> This discourse resembles farewell speeches called testaments, in which a father or religious leader, often on the deathbed, leaves instructions for his children or followers.{{sfn|Funk|Hoover|1993|p=}} |

|||

The sermon goes on to talk of Jesus sending a ''[[paraclete]]'' from God, a ''Spirit of Truth'' that will ''testify about'' Jesus. Though ''paraclete'' means ''counsellor'', when the concept of a [[Trinity]] arose in the 3rd century the ''paraclete'' became interpreted as the ''[[Holy Ghost]]'', and the passage became central to the arguments about the ''[[filioque clause]]'' which partly caused the [[Great Schism]]. Prior to the development of the idea of a Trinity, the ''paraclete'' was considered a more human figure, and, in the 2nd century, [[Montanus]] claimed to be the ''paraclete'' that had been promised. |

|||

This sermon is referred to as the Farewell discourse of Jesus, and has historically been considered a source of Christian [[doctrine]], particularly on the subject of [[Christology]]. John 17:1–26 is generally known as the ''Farewell Prayer'' or the ''High Priestly Prayer'', given that it is an intercession for the coming Church.{{sfn | Ridderbos | 1997 | pp= 546–76}} The prayer begins with Jesus's petition for his glorification by the Father, given that completion of his work and continues to an intercession for the success of the works of his disciples and the community of his followers.{{sfn | Ridderbos | 1997 | pp= 546–76}} |

|||

==Time and place== |

|||

===Date=== |

|||

[[File:Icon last supper.jpg|thumb|13th century [[Eastern Orthodox Church|Orthodox]] Russian [[icon]] from 1497]] |

|||

{{See also|Chronology of Jesus}} |

|||

Historians estimate that the date of the crucifixion fell in the range AD 30–36.{{sfn|Barnett|2002|pp=19-21}}{{sfn | Riesner | 1998 | pp=19-27}}{{sfn | Köstenberger|Kellum|Quarles |2009 | pp=77-79}} [[Isaac Newton]] and [[Colin Humphreys]] have ruled out the years 31, 32, 35, and 36 on astronomical grounds, leaving 7 April AD 30 and 3 April AD 33 as possible crucifixion dates.{{sfn|Humphreys|2011|pp=62-63}} {{harvnb|Humphreys|2011|pp=72, 189}} proposes narrowing down the date of the Last Supper as having occurred in the evening of Wednesday, 1 April AD 33, by revising Annie Jaubert's double-Passover theory. |

|||

Historically, various attempts to reconcile the three synoptic accounts with John have been made, some of which are indicated in the Last Supper by Francis Mershman in the 1912 [[Catholic Encyclopedia]].{{Sfn|Mershman|1912}} The [[Maundy Thursday]] church tradition assumes that the Last Supper was held on the evening before the crucifixion day (although, strictly speaking, in no Gospel is it unequivocally said that this meal took place on the night before Jesus died).{{sfn|Green|1990|p=333}} |

|||

==Last Supper Remembrances== |

|||

[[Image:Germany Rothenberg Last Supper.jpg|thumb|200px|right|The Last Supper from the Heilig-Blut-Altar by [[Tilman Riemenschneider]] in St-Jakobskirche, [[Rothenburg ob der Tauber]], Germany]] |

|||

[[Image:Simon ushakov last supper 1685.jpg|thumb|200px|right|[[Simon Ushakov]]'s the Last Supper.]] |

|||

[[Image:Jacopo Bassano Last Supper 1542.jpeg|right|thumbnail|200px|[[Jacopo Bassano]]'s the Last Supper]] |

|||

The institution of the Eucharist at the Last Supper is remembered by Roman Catholics as one of the Luminous Mysteries of the [[Rosary]], and by most Christians as the "inauguration of the [[New Covenant (theology)|New Covenant]]", mentioned by the prophet [[Jeremiah]], fulfilled by Jesus at the Last Supper, when He said, "Take, eat; this [bread] is My Body; which is broken for you. Par-take of the cup, drink; this [wine] is My Blood, which is shed for many; for the remission of sins". Other Christian groups consider the Bread and Wine remembrance as a change to the [[Passover (Christian Holy Day)|Passover]] ceremony, as Jesus Christ has become "our Passover, sacrificed for us" (I Corinthians 5:7). Partaking of the Passover Communion (or fellowship) is now the sign of the New Covenant, when properly understood by the practicing believer. |

|||

A new approach to resolve this contrast was undertaken in the wake of the excavations at [[Qumran]] in the 1950s when Annie Jaubert argued that there were two Passover feast dates: while the official Jewish lunar calendar had Passover begin on a Friday evening in the year that Jesus died, a solar calendar was also used, for instance by the [[Essene]] community at [[Qumran]], which always had the Passover feast begin on a Tuesday evening. According to Jaubert, Jesus would have celebrated the Passover on Tuesday, and the Jewish authorities three days later, on Friday.<ref>{{Cite web |title=The Last Supper, Paul and Qumran: The Tail that Wagged the Dog {{!}} Bible Interp |url=https://bibleinterp.arizona.edu/articles/last-supper-paul-and-qumran-tail-wagged-dog |access-date=2024-03-28 |website=bibleinterp.arizona.edu}}</ref> |

|||

Each major division of Christianity has formed a different theology about the exact meaning and purpose of these remembrance ceremonies, but most of them contain similarities. |

|||

Humphreys has disagreed with Jaubert's proposal on the grounds that the Qumran solar Passover would always fall {{em|after}} the official Jewish lunar Passover. He agrees with the approach of two Passover dates, and argues that the Last Supper took place on the evening of Wednesday 1 April 33, based on his recent discovery of the Essene, [[Samaritan]], and [[Zealots (Judea)|Zealot]] {{em|lunar}} calendar, which is based on Egyptian reckoning.{{sfn|Humphreys|2011|pp=162, 168}}{{sfn|Narayana|2011}} |

|||

In a review of Humphreys' book, the Bible scholar William R Telford points out that the non-astronomical parts of his argument are based on the assumption that the chronologies described in the New Testament are historical and based on eyewitness testimony. In doing so, Telford says, Humphreys has built an argument upon unsound premises which "does violence to the nature of the biblical texts, whose mixture of fact and fiction, tradition and redaction, history and myth all make the rigid application of the scientific tool of astronomy to their putative data a misconstrued enterprise."{{sfn|Telford|2015|pp=371-376}} |

|||

===Development in the Early Church=== |

|||

[[Christianity|Early Christianity]] has created a remembrance service that took place in the form of meals known as ''[[agape feast]]s'': perhaps Jude, and the apostle Paul have referred to these as ''your love-feasts'', by way of warning (about ''who shows up'' to these). ''[[Agape]]'' is one of the five main [[Greek words for love]], and refers to the ''idealised'' love, rather than ''lust'', ''friendship'', ''hospitality'', or ''affection'' (as in ''parental affection''). Though Christians interpret ''Agape'' as meaning a ''divine'' form of love beyond ''human'' forms, in modern Greek the term is used in the sense of ''I love you'' - i.e. ''romantic love''. |

|||

===Location=== |

|||

These ''love feasts'' were apparently a full meal, with each participant bringing their own food, and with the meal eaten in a common room. |

|||

{{Main|Cenacle}} |

|||

Early Christianity observed a ritual meal known as the "[[agape feast]]" held on Sundays which became known as the Day of the Lord, to recall the resurrection, the appearance of Christ to the disciples on the road to Emmaus, the appearance to Thomas and the Pentecost which all took place on Sundays after the Passion. Jude, and the apostle Paul referred to these as "your love-feasts", by way of warning (about "who shows up" to these). ''[[Agape]]'' is one of the [[Greek language|Greek]] words for ''love'', and refers to the "divine" type of love, rather than mere human forms of love. Following the meal, as at the Last Supper, the apostle, bishop or priest prayed the words of institution over bread and wine which was shared by all the faithful present. In the later half of the first century, especially after the martyrdom of Peter and Paul, passages from the writings of the apostles were read and preached upon before the blessing of the bread and wine took place. |

|||

[[File:Cenacle on Mount Zion.jpg|thumb|left|The [[Cenacle]] on [[Mount Zion]], claimed to be the location of the Last Supper and [[Pentecost]].]] |

|||

According to later tradition, the Last Supper took place in what is today called The [[Cenacle|Room of the Last Supper]] on [[Mount Zion]], just outside the walls of the [[Old City (Jerusalem)|Old City]] of [[Jerusalem]], and is traditionally known as The Upper Room. This is based on the account in the [[Synoptic Gospels]] that states that Jesus had instructed two disciples (Luke 22:8 specifies that Jesus sent Peter and John) to go to "the city" to meet "a man carrying a jar of water", who would lead them to a house, where they would find "a large upper room furnished and ready".<ref>{{bibleverse|Mark|14:13–15}}</ref> In this upper room they "prepare the Passover". |

|||

No more specific indication of the location is given in the New Testament, and the "city" referred to may be a [[suburb]] of Jerusalem, such as Bethany, rather than Jerusalem itself. |

|||

These meals evolved into more formal worship services and became codified as the [[Eucharist (Catholic Church)|Mass]] in Catholic Church, and as the [[Divine Liturgy]] in the [[Eastern Orthodox Church|Orthodox Church]]es. At these liturgies, Catholics and Eastern Orthodox celebrate the Sacrament of the Eucharist. The name ''Eucharist'' is from the Greek word ''eucharistos'' which means ''thanksgiving''. |

|||

A structure on [[Mount Zion]] in Jerusalem is currently called [[Cenacle|the Cenacle]] and is purported to be the location of the Last Supper. [[Bargil Pixner]] claims the original site is located beneath the current structure of the Cenacle on [[Mount Zion]].{{sfn|Pixner|1990}} |

|||

===Name=== |

|||

Within many [[Christian]] traditions, the name [[Holy Communion]] is used. This name emphasizes the nature of the service, as a "joining in common" between [[God]] and humans, which is made possible, or facilitated due to the sacrifice of Jesus. Catholics typically restrict the term 'communion' to the reception of the Body and Blood of Christ by the communicants during the celebration of the [[Eucharist (Catholic Church)|Mass]]. |

|||

The traditional location is in an area that, according to [[archaeology]], had a large [[Essenes|Essene]] community, a point made by scholars who suspect a link between Jesus and the group.<ref name="Kilgallen" /> |

|||

Another variation of the name of the service is "[[The Lords Supper|The Lord's Supper]]". This name usually is used by the churches of minimalist traditions; such as those strongly influenced by [[Zwingli]]. Some echoes of the "agape meal" may remain in ''fellowship'', or ''[[potluck]]'' dinners held at some churches. |

|||

[[Monastery of Saint Mark|Saint Mark's Syrian Orthodox Church in Jerusalem]] is another possible site for the room in which the Last Supper was held, and contains a Christian stone inscription testifying to early reverence for that spot. Certainly the room they have is older than that of the current cenaculum (crusader – 12th century) and as the room is now underground the relative altitude is correct (the streets of 1st century Jerusalem were at least {{convert|12|ft|m|abbr=off|spell=in}} lower than those of today, so any true building of that time would have even its upper story currently under the earth). They also have a revered Icon of the Virgin Mary, reputedly painted from life by St Luke. |

|||

As well, [[The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints]] commonly refers to the service as ''The Sacrament''. |

|||

==Theology of the Last Supper== |

|||

==See also== |

|||

{{commonscat|Last Supper}} |

|||

*[[New Covenant (theology)]] |

|||

*[[Round dance of the cross]] |

|||

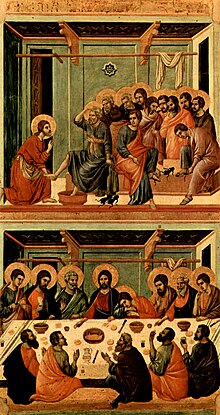

[[File:Duccio di Buoninsegna 029.jpg|thumb|The ''[[Washing the feet of the Apostles|Washing of Feet]]'' and the Supper, from the ''[[Maestà (Duccio)|Maesta]]'' by [[Duccio]], 1308–1311.]] |

|||

==Notes== |

|||

<references/> |

|||

The ''[[Washing the feet of the Apostles|Washing of Feet]]'' and the Supper, from the ''[[Maestà (Duccio)|Maesta]]'' by [[Duccio]], 1308–1311. Peter often displays amazement in feet washing depictions, as in John 13:8.<ref>{{Bibleref2|John|13:8}}</ref> St. [[Thomas Aquinas]] viewed [[God the Father|The Father]], Christ, and the [[Holy Spirit (Christianity)|Holy Spirit]] as teachers and masters who provide lessons, at times by example. For Aquinas, the Last Supper and the Cross form the summit of the teaching that wisdom flows from intrinsic grace, rather than external power.{{sfn|Dauphinais|Levering|2005|p=xix}} For Aquinas, at the Last Supper Christ taught by example, showing the value of humility (as reflected in John's foot washing narrative) and self-sacrifice, rather than by exhibiting external, miraculous powers.{{sfn|Dauphinais|Levering |2005|p=xix}}{{sfn | Wawrykow | 2005a | pp=124–125}} |

|||

Aquinas stated that based on John 15:15 (in the Farewell discourse), in which Jesus said: "No longer do I call you servants; ...but I have called you friends,"<ref>{{Bibleref2|John|15:15}}</ref> those who are followers of Christ and partake in the [[Sacrament]] of the Eucharist become his friends, as those gathered at the table of the Last Supper.{{sfn|Dauphinais|Levering |2005|p=xix}}{{sfn | Wawrykow | 2005a | pp=124–125}}{{sfn | Pope | 2002 | p=22}} For Aquinas, at the Last Supper Christ made the promise to be present in the Sacrament of the Eucharist, and to be with those who partake in it, as he was with his disciples at the Last Supper.{{sfn | Wawrykow | 2005b | p=124}} |

|||

[[John Calvin]] believed only in the two sacraments of [[Baptism]] and the "Lord's Supper" (i.e., Eucharist). Thus, his analysis of the Gospel accounts of the Last Supper was an important part of his entire theology.{{sfn|Rice|Huffstutler|2001|pp=66-68}}{{sfn | Chen | 2008 | pp=62-68}} Calvin related the Synoptic Gospel accounts of the Last Supper with the [[Bread of Life Discourse]] in John 6:35 that states: "I am the bread of life. He who comes to me will never go hungry."<ref>{{Bibleref2|John|6:35}}</ref>{{sfn | Chen | 2008 | pp=62-68}} |

|||

Calvin also believed that the acts of Jesus at the Last Supper should be followed as an example, stating that just as Jesus gave thanks to the Father before breaking the bread,<ref>{{bibleverse|1Cor|11:24||1 Cor. 11:24}}</ref> those who go to the "Lord's Table" to receive the sacrament of the Eucharist must give thanks for the "boundless love of God" and celebrate the sacrament with both joy and thanksgiving.{{sfn | Chen | 2008 | pp=62-68}} |

|||

==Remembrances== |

|||

{{Main|Maundy Thursday}} |

|||

{{See also|Agape feast}} |

|||

[[Image:Simon ushakov last supper 1685.jpg|thumb|left|[[Simon Ushakov]]'s [[icon]] of the ''Mystical Supper'', 1685]] |

|||

The institution of the Eucharist at the Last Supper is remembered by Roman Catholics as one of the [[Luminous Mysteries]] of the [[Rosary]], the First Station of a so-called [[Scriptural Way of the Cross#New Way of the Cross|New Way of the Cross]] and by Christians as the "inauguration of the [[New Covenant (theology)|New Covenant]]", mentioned by the prophet [[Jeremiah]], fulfilled at the last supper when Jesus "took bread, and after blessing it broke it and gave it to them, and said, 'Take; this is my body.' And he took a cup, and when he had given thanks he gave it to them, and they all drank of it. And he said to them, 'This is my blood of the covenant, which is poured out for many.{{' "}}<ref>{{bibleverse|Mk.|14:22–24}}, {{bibleverse|Mt.|26:26–28}}, {{bibleverse|Lk.|22:19–20}}</ref> Other Christian groups consider the Bread and Wine remembrance to be a change to the [[Passover (Christian Holy Day)|Passover]] ceremony, as Jesus Christ has become "our Passover, sacrificed for us",<ref>{{bibleverse|1cor|5:7||1 Cor. 5:7}}</ref> and hold that partaking of the Passover Communion (or fellowship) is now the sign of the New Covenant, when properly understood by the practicing believer. |

|||

These meals evolved into more formal worship services and became codified as the [[Eucharist (Catholic Church)|Mass]] in the Catholic Church, and as the [[Divine Liturgy]] in the Eastern Orthodox Church; at these liturgies, Catholics and Eastern Orthodox celebrate the Sacrament of the Eucharist. The name "Eucharist" is from the Greek word ''εὐχαριστία'' (eucharistia) which means "thanksgiving". |

|||

[[Early Christianity]] observed a ritual meal known as the "[[agape feast]]"{{efn|name=FourLoves}} These "love feasts" were apparently a full meal, with each participant bringing food, and with the meal eaten in a common room. They were held on Sundays, which became known as the [[Lord's Day]], to recall the resurrection, the appearance of Christ to the disciples on the [[road to Emmaus]], the [[Doubting Thomas|appearance to Thomas]] and the [[Pentecost]] which all took place on Sundays after the Passion. |

|||

==Passover parallels== |

|||

[[File:The-Last-Supper-large.jpg|thumbnail|''Last Supper'', [[Carl Bloch]]. In some depictions [[John the Apostle]] is placed on the right side of Jesus, some to the left.]] |

|||

Since the late 20th century, with growing consciousness of the Jewish character of the early church and the improvement of Jewish-Christian relations, it became common among some evangelical groups to borrow Seder customs, like [[Haggadah]]s, and incorporated them in new rituals meant to mimic the Last Supper.{{citation needed|date=April 2022}} As the earliest elements in the current Passover Seder (''a fortiori'' the full-fledged ritual, which is first recorded in full only in the ninth century) are a [[Rabbinic Judaism|rabbinic enactment]] instituted in remembrance of the Temple, which was still standing during the Last Supper,{{sfn|Poupko|Sandmel|2017}} the Seder in Jesus' time would have been celebrated quite differently, however. |

|||

== In Islam == |

|||

The fifth chapter in the [[Quran]], ''[[Al-Ma'ida]]'' (the table) contains a reference to a meal (Sura 5:114) with a table sent down from God to [[Jesus in Islam|ʿĪsá]] (i.e., Jesus) and the apostles (Hawariyyin). However, there is nothing in Sura 5:114 to indicate that Jesus was celebrating that meal regarding his impending death, especially as the Quran states that Jesus was never crucified to begin with. Thus, although Sura 5:114 refers to "a meal", there is no indication that it is the Last Supper.{{sfn|Beaumont |2005|p=145}} However, some scholars believe that Jesus' manner of speech during which the table was sent down suggests that it was an affirmation of the apostles' resolves and to strengthen their faiths as the impending trial was about to befall them.{{sfn|Khalife|2012}} |

|||

==Historicity== |

|||

[[File:Michael Damaskinos The Last Supper.png|thumb|250 px|left| |

|||

''[[The Last Supper (Damaskinos)|The Last Supper]]'' by [[Michael Damaskinos]] circa 1591]] |

|||

According to [[John P. Meier]] and [[E. P. Sanders]], Jesus having a final meal with his disciples is almost beyond dispute among scholars, and belongs to the framework of the narrative of Jesus' life.{{sfn|Sanders|1995|pp=10-11}}{{sfn|Meier|1991|p=398}} [[I. Howard Marshall]] states that any doubt about the historicity of the Last Supper should be abandoned.{{Sfn|Marshall|2006|p=33}} |

|||

Some [[Jesus Seminar]] scholars consider the Last Supper to have derived not from Jesus' last supper with the disciples but rather from the [[gentile]] tradition of memorial dinners for the dead.{{sfn|Funk|1998|pp=51-161|loc=Mark}} In their view, the Last Supper is a tradition associated mainly with the gentile churches that Paul established, rather than with the earlier, Jewish congregations.{{sfn|Funk|1998|pp=51-161|loc=Mark}} Such views echo that of 20th century Protestant theologian [[Rudolf Bultmann]], who also believed the Eucharist to have originated in [[Pauline Christianity|Gentile Christianity]].{{Sfn|Bultmann|1963}}{{Sfn|Bultmann|1958}} |

|||

On the other hand, an increasing number of scholars have reasserted the historicity of the institution of the Eucharist, reinterpreting it from a [[Jewish eschatology|Jewish eschatological]] point of view: according to Lutheran theologian [[Joachim Jeremias]], for example, the Last Supper should be seen as a climax of a series of Messianic meals held by Jesus in anticipation of a new [[The Exodus|Exodus]].{{Sfn|Jeremias|1966|p=51-62}} Similar views are echoed in more recent works by Catholic biblical scholars such as [[John P. Meier]] and [[Brant Pitre]], and by Anglican scholar [[N. T. Wright|N.T. Wright]].{{Sfn|Meier|1994|pp=302-309}}{{Sfn|Pitre|2011}}{{Sfn|Wright|2014}} |

|||

==Artistic depictions== |

|||

{{Main|Last Supper in Christian art}} |

|||

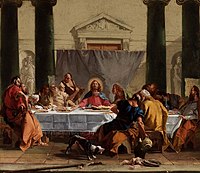

The Last Supper has been a popular subject in [[Christian art]].{{sfn|Zuffi|2003|pp=254-259}} Such depictions date back to [[early Christianity]] and can be seen in the [[Catacombs of Rome]]. [[Byzantine]] artists frequently focused on the Apostles receiving Communion, rather than the reclining figures having a meal. By the [[Renaissance]], the Last Supper was a favorite topic in Italian art.{{sfn | McNamee | 1998 | p=22–32}} |

|||

There are three major themes in the depictions of the Last Supper: the first is the dramatic and dynamic depiction of Jesus's [[Jesus predicts his betrayal|announcement of his betrayal]]. The second is the moment of the institution of the tradition of the Eucharist. The depictions here are generally solemn and mystical. The third major theme is the [[Farewell discourse|farewell of Jesus to his disciples]], in which [[Judas Iscariot]] is no longer present, having left the supper. The depictions here are generally melancholy, as Jesus prepares his disciples for his departure.{{sfn|Zuffi|2003|pp=254-259}} There are also other, less frequently depicted scenes, such as the washing of the feet of the disciples.{{sfn|Zuffi|2003|p=252}} |

|||

The best known depiction of the Last Supper is [[Leonardo da Vinci]]'s [[The Last Supper (Leonardo)|''The Last Supper'']], which is considered the first work of [[High Renaissance]] art, due to its high level of harmony.{{sfn | Buser | 2006 | pp=382–383}} |

|||

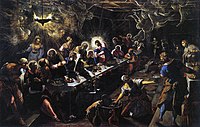

Among other representations, [[Last Supper (Tintoretto)|Tintoretto's depiction]] is unusual in that it includes secondary characters carrying or taking the dishes from the table,{{sfn | Nichols | 1999 | p=234}} and [[The Sacrament of the Last Supper|Salvador Dali's depiction]] combines the typical Christian themes with modern approaches of [[Surrealism]].{{sfn | Stakhov | Olsen | 2009 | pp=177-178}} |

|||

<gallery widths="200px" heights="200px" perrow="5" caption="Depictions of Last Supper"> |

|||

File:Last Supper miniature from a Psalter c1220-40.png|Miniature depiction from {{circa|1230}} |

|||

File:Comunione degli apostoli, cella 35.jpg|''Communion of the Apostles'', by [[Fra Angelico]], with [[donor portrait]], 1440–41 |

|||

File:Jaume Huguet - Last Supper - WGA11797.jpg|''Last Supper'' by [[Jaume Huguet]], {{circa|1470}} |

|||

File:Domenico ghirlandaio, cenacolo di ognissanti 01.jpg|[[Domenico Ghirlandaio]], 1480, depicting Judas separately |

|||

File:The Last Supper - Leonardo Da Vinci - High Resolution 32x16.jpg|''[[The Last Supper (Leonardo)|The Last Supper]]'', by [[Leonardo da Vinci]], late 15th century |

|||

File:Wrocław Last Supper.jpg|''Last Supper'', sculpture, {{circa|1500}} |

|||

File:Última Cena - Juan de Juanes.jpg|The first Eucharist, depicted by [[Juan de Juanes]] in ''The Last Supper'', {{circa|1562}} |

|||

File:Jacopo Tintoretto - The Last Supper - WGA22649.jpg|''[[Last Supper (Tintoretto)|The Last Supper]]'', by [[Tintoretto]], 1592–1594 |

|||

File:Valentin de Boulogne, Last Supper.jpg|[[Valentin de Boulogne]], 1625–1626 |

|||

File:The Last Supper (Dark side of the Eucharist), 1786 by Benjamin West.png|''The Last Supper (Dark side of the Eucharist)'', by [[Benjamin West]], mid 18 century |

|||

File:Tiepolo Last Supper.jpg|''Last Supper'' by [[Tiepolo]], {{circa|1760}} |

|||

File:Bouveret Last Supper.jpg|''The Last Supper'', by [[Pascal Dagnan-Bouveret|Bouveret]], 19th century |

|||

File:Last Supper (Pisani).jpg|''[[The Last Supper (Pisani)|The Last Supper]]'' by [[Lazzaro Pisani]], 1917, the altarpiece of Corpus Christi Parish Church in Għasri, Malta |

|||

File:Laatste Avondmaal, Gustave van de Woestyne, 1927, Groeningemuseum, 0040054000.jpg|''Last Supper'', by [[Gustave Van de Woestijne]], 1927 |

|||

</gallery> |

|||

== Music == |

|||

The Lutheran Passion hymn "''[[Da der Herr Christ zu Tische saß]]''" (''When the Lord Christ sat at the table'') derives from a depiction of the Last Supper.{{importance example|date=March 2020|reason=Basically every Communion hymn ever}} |

|||

==See also== |

|||

{{Portal|Art|Christianity}} |

|||

* ''[[Book of the Secret Supper]]'' |

|||

* [[Friday the 13th]] |

|||

* [[Life of Jesus in the New Testament]] |

|||

* [[List of dining events]] |

|||

==References== |

==References== |

||

===Notes=== |

|||

*Brown, Raymond E. ''An Introduction to the New Testament'' Doubleday 1997 ISBN 0-385-24767-2 |

|||

{{notelist|refs= |

|||

*Brown, Raymond E. et al. ''The New Jerome Biblical Commentary'' Prentice Hall 1990 ISBN 0-13-614934-0 |

|||

{{efn|name=FourLoves|''[[Agape]]'' is one of the four main [[Greek words for love]] {{harv|Lewis|1960|p=}}. It refers to the ''idealised'' or high-level unconditional love rather than ''lust'', ''friendship'', or ''affection'' (as in ''parental affection''). Though Christians interpret ''Agape'' as meaning a ''divine'' form of love beyond human forms, in modern Greek the term is used in the sense of "I love you" (''romantic love'').}} |

|||

*Bultmann, Rudolf ''The Gospel of John'' Blackwell 1971 |

|||

*Kilgallen, John J. ''A Brief Commentary on the Gospel of Mark'' Paulist Press 1989 ISBN 0-8091-3059-9 |

|||

}} |

|||

*Linders, Barnabus ''The Gospel of John'' Marshal Morgan and Scott 1972 |

|||

===Citations=== |

|||

{{Reflist|refs= |

|||

<ref name=Brown>Brown et al. 626{{incomplete short citation|date=August 2021}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name=Kilgallen>Kilgallen 265{{incomplete short citation|date=March 2020}}</ref> |

|||

}} |

|||

===Sources=== |

|||

{{refbegin|30em|indent=yes}} |

|||

*{{cite book | author=Anon. | title=Liturgical Year: The Worship of God | publisher=Presbyterian Publishing Corporation | series=Supplemental liturgical resource | year=1992 | isbn=978-0-664-25350-9 | url=https://books.google.com/books?id=NSZzNot1iCsC&pg=PA37 }} |

|||

* {{cite book | last1=Armentrout | first1=D.S. | last2=Slocum | first2=R.B. | title=An Episcopal Dictionary of the Church: A User-Friendly Reference for Episcopalians | publisher=Church Publishing Incorporated | year=1999 | isbn=978-0-89869-211-2 | url=https://books.google.com/books?id=QNM8AwAAQBAJ&pg=PA292 }} |

|||

*{{cite book|title=Jesus and the Rise of Early Christianity|series= A History of New Testament Times |first=Paul |last=Barnett |date=2002|isbn=0-8308-2699-8|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=NlFYY_iVt9cC}} |

|||

*{{cite book|title=Christology in dialogue with Muslims|first=Ivor Mark |last=Beaumont|date= 2005|isbn=1-870345-46-0}} |

|||

*{{cite book | last=Blomberg | first=Craig | title=Jesus and the Gospels | publisher=B & H Pub. Group | publication-place=Nashville | year=2009 | isbn=978-1-4336-6842-5 | oclc=727647948}} |

|||

*{{cite book | last=Bower | first=Peter | title=The companion to the Book of common worship | publisher=Geneva Press Office of Theology and Worship, Presbyterian Church (U.S.A | publication-place=Louisville, Ky | year=2003 | isbn=0-664-50232-6 | oclc=51059177}} |

|||

* {{Cite book |last=Bultmann |first=Rudolf |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=V87YAAAAMAAJ |title=The History of the Synoptic Tradition |date=1963 |publisher=Harper & Row |isbn=978-0-06-061172-9 |language=en}} |

|||

* {{Cite book |last=Bultmann |first=Rudolf |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=aQ8XAAAAIAAJ |title=Jesus and the Word |date=1958 |publisher=Scribner |isbn=978-0-684-14390-3 |language=en}} |

|||

*{{cite book | last=Buser | first=Thomas | title=Experiencing art around us | publisher=Thomson Wadsworth | publication-place=Australia United States | year=2006 | isbn=978-0-534-64114-6 | oclc=58986528}} |

|||

*{{Cite book|last=Casey|first=Maurice|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=lXK0auknD0YC&pg=PA436|title=Jesus of Nazareth: An Independent Historian's Account of His Life and Teaching|date=2010|publisher=A&C Black|isbn=978-0-567-64517-3}} |

|||

*{{cite book | last=Chen | first=David | title=Calvin's passion for the church and the Holy Spirit | publisher=Xulon Press | publication-place=United States | year=2008 | isbn=978-1-60647-346-7 | oclc=459711693}} |

|||

*{{cite book | last1=Cox | first1=Steven | title=Harmony of the Gospels | publisher=Holman Bible Pub | publication-place=Nashville, Tenn | year=2007 | isbn=978-0-8054-9444-0 | oclc=83596188|first2= Kendell H. |last2=Easley}} |

|||

*{{cite book|last=Bromiley|first= G. W. |date=1979|volume= 3|title= The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia|publisher= Wm. B. Eerdmans|isbn= 978-0-8028-3783-7 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Zkla5Gl_66oC&pg=PA164}} |

|||

*{{cite book|last1=Cross|first1= F. L.|last2= Livingstone|first2= E. A.|date=2005|title= The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church |edition=3rd rev.|location= Oxford; New York|publisher= Oxford University Press|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=fUqcAQAAQBAJ&pg=PA958|author1-link=Frank Leslie Cross|isbn=978-0-19-280290-3}} |

|||

*{{cite book|title=Reading John with St. Thomas Aquinas|editor1-first= Michael |editor1-last=Dauphinais|editor2-first= Matthew |editor2-last=Levering |date=2005|publisher= CUA Press |isbn=978-0-8132-1405-4|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=dzLgT7cauloC&pg=PR19}} |

|||

*{{cite book|author-link=Gregory Dix|last=Dix|first=Gregory}|title=The Shape of the Liturgy|publisher= Dacre Press|date=1945}} |

|||

*{{cite book|author-link=Bart D. Ehrman|last=Ehrman|first= Bart D.|title=Misquoting Jesus: The Story Behind Who Changed the Bible and Why|title-link=Misquoting Jesus|publisher= HarperCollins|date= 2005|isbn=978-0-06-073817-4}} |

|||

*{{Cite web|last=Ehrman|first=Bart D.|title=Did Matthew Write in Hebrew? Did Jesus Institute the Lord's Supper? Did Josephus Mention Jesus? Weekly Readers' Mailbag July 9, 2016|url=https://ehrmanblog.org/did-matthew-write-in-hebrew-did-jesus-institute-the-lords-supper-did-josephus-mention-jesus-weekly-readers-mailbag-july-9-2016/|access-date=2021-07-09|website=The Bart Ehrman Blog|date=9 July 2016}} |

|||

*{{cite book|title=The Bible Knowledge Background Commentary|first=Craig A. |last=Evans|date= 2003 |isbn=0-7814-3868-3|publisher=David C Cook|url=}} |

|||

*{{cite book|title=The Encyclopedia of Christianity|volume= 4|first= Erwin |last=Fahlbusch|date= 2005 |publisher= Wm. B. Eerdmans|isbn=978-0-8028-2416-5}} |

|||

*{{cite book | editor-last=Fitzmyer |editor-first=Joseph | title=The Gospel according to Luke: introduction, translation, and notes | publisher=Doubleday | publication-place=Garden City, N.Y | year=1981 | isbn=0-385-00515-6 | oclc=6918343|volume=28A}} |

|||

*{{cite book | last=Freedman | first=D. N. | title=Eerdmans dictionary of the Bible | publisher=Eerdmans | publication-place=Grand Rapids, MI | year=2000 | isbn=90-5356-503-5 | oclc=782943561}} |

|||

*{{cite book|author-link=Robert W. Funk|last1=Funk|first1= Robert W.|others= [[Jesus Seminar]]|first2= Roy W. |last2=Hoover |title=The five gospels|publisher= HarperSanFrancisco|date= 1993}} |

|||

*{{cite book|author-link=Robert W. Funk|last=Funk|first= Robert W.|others= [[Jesus Seminar]]|title=The acts of Jesus: the search for the authentic deeds of Jesus|publisher= HarperSanFrancisco|date= 1998}} |

|||

*{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=cgEmAQAAIAAJ&q=%22Annie+Jaubert%22+%22Last+Supper%22|title=Judaism and Christianity in the first century|isbn=978-0-8240-8174-4|last1=Green|first1=William Scott|year=1990|publisher=Garland }} |

|||

*{{cite book | last=Harrington | first=Daniel | title=The church according to the New Testament: what the wisdom and witness of early Christianity teach us today | publisher=Sheed & Ward | publication-place=Franklin, Wis | year=2001 | isbn=1-58051-111-2 | oclc=47869562}} |

|||

*{{cite book|author-link=Stephen L Harris|last=Harris|first= Stephen L.|title= Understanding the Bible|location= Palo Alto|publisher= Mayfield|date= 1985|chapter=John}} |

|||

*{{cite book|url = https://books.google.com/books?id=edXChxGzxgoC&pg=PA34 |title = Inside Christianity|publisher=Lorenz Educational Press|first=Walter |last=Hazen|date=2002|isbn = 978-0-7877-0559-6}} |

|||

*{{cite book|author-link=Colin Humphreys|first=Colin J. |last=Humphreys|title=The Mystery of the Last Supper|location= Cambridge|publisher= University Press |date=2011|isbn=978-0-521-73200-0|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=BEy1BZRRAPQC&pg=PA62}} |

|||

* {{cite book | last=Jeremias | first=J. |author-link=Joachim Jeremias| title=The Eucharistic Words of Jesus | publisher=Scribner | series=New Testament library | year=1966 | url=https://books.google.com/books?id=GNdHAQAAIAAJ}} |

|||

* {{cite book | last1=Kasser | first1=R. | last2=Meyer | first2=M. | last3=Wurst | first3=G. | last4=Gaudard | first4=F. | title=The Gospel of Judas, Second Edition | publisher=National Geographic Society | year=2008 | isbn=978-1-4262-0415-9 | url=https://books.google.com/books?id=6rVR4h019R4C&pg=PA11}} |

|||

*{{cite web|title=Last Supper of Jesus According to Islam|first=Maan|last=Khalife|year=2012|url=http://www.onislam.net/english/ask-about-islam/faith-and-worship/quran-and-scriptures/460307-last-supper-of-jesuspbuh.html?Scriptures=}} |

|||

*{{cite book | last=Köstenberger| first=Andreas | title=Encountering John: the Gospel in historical, literary, and theological perspective | publisher=Baker Academic | publication-place=Grand Rapids, Mich | year=2002 | isbn=0-8010-2603-2 | oclc=52964348|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Joglgt0gQL4C}} |

|||

*{{cite book | last1=Köstenberger| first1=Andreas J.|first2=Leonard Scott |last2=Kellum|first3= Charles L.|last3= Quarles| title=The cradle, the cross, and the crown: an introduction to the New Testament | publisher=B & H Academic | publication-place=Nashville, Tenn | year=2009 | isbn=978-0-8054-4365-3 | oclc=369138111|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=g-MG9sFLAz0C&pg=PA77}} |

|||

*{{cite book|title=The Gospel according to John|first= Colin G.|last= Kruse|date= 2004 |isbn=0-8028-2771-3}} |

|||

*{{cite book|title=The Gospel according to Matthew|volume= 1|first= Johann Peter |last=Lange |date=1865 |publisher= Charles Scribner |location=New York|url=https://archive.org/details/gospelaccordingt00lang}} |

|||

*{{cite book|title=The Four Loves|author-link=C. S. Lewis|first=C. S.|last= Lewis|date=1960|title-link=The Four Loves|publisher=Geoffrey Bles|oclc=30879763}} |

|||

* {{Cite book |last=Marshall |first=I. Howard |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=4-1QAAAACAAJ |title=The Last Supper and the Lord's Supper |date=2006 |publisher=Regent College Publishing |isbn=978-1-57383-318-9 |language=en}} |

|||

*{{cite book | first1=I. Howard |last1=Marshall|first2=A. R.|last2= Millard|first3= J. I. |last3=Packer|first4=by Donald J. |last4=Wiseman| title=New Bible dictionary | publisher=InterVarsity Press | publication-place=Leicester| year=1996 | isbn=978-0-8308-1439-8 | oclc=34943226 | edition=3rd}} |

|||

*{{cite book | last=McGuckin | first=John | title=The Orthodox Church: an Introduction to its History, Doctrine, and Spiritual Culture | publisher=John Wiley & Sons, Ltd | publication-place=Hoboken | year=2010 | isbn=978-1-4443-3731-0 | oclc=811493276}} |

|||

*{{cite book | last=McNamee | first=Maurice | title=Vested angels: eucharistic allusions in early Netherlandish paintings | publisher=Peeters | publication-place=Leuven | year=1998 | isbn=978-90-429-0007-3 | oclc=39715499}} |

|||

*{{Cite book|last=Meier|first=John P.|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=zODYAAAAMAAJ|title=A Marginal Jew: The roots of the problem and the person|date=1991 |volume=One|publisher=Doubleday|isbn=978-0-385-26425-9|page=398|language=en}} |

|||

* {{Cite book |last=Meier |first=John P. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=SNFTIQAACAAJ |title=A Marginal Jew: Rethinking the Historical Jesus |volume=II: Mentor, Message, and Miracles |date=November 1994 |publisher=Yale University Press |isbn=978-0-300-14033-0 |language=en}} |

|||

* {{CathEncy|wstitle=The Last Supper|year=1912|last=Mershman|first=Francis|volume=14}} |

|||

*{{cite news |url=http://www.ibtimes.com/articles/135477/20110418/colin-humphreys-last-supper-challenge-biblical-calendar-jewish-calendar-final-days-of-jesus-good-fri.htm |title=Last Supper was on Wednesday, not Thursday, challenges Cambridge professor Colin Humphreys.| newspaper=[[International Business Times]] |date=18 April 2011|first=Nagesh|last= Narayana|access-date=2021-08-28 }} |

|||

*{{cite book | last=Nichols | first=Tom | title=Tintoretto: tradition and identity | publisher=Reaktion | publication-place=London | year=1999 | isbn=1-86189-120-2 | oclc=41958923}} |

|||

*{{cite book | last=Perkins | first=Pheme | title=Peter: apostle for the whole church | publisher=T. & T. Clark | publication-place=Edinburgh | year=2000 | isbn=0-567-08743-3 | oclc=746853124}} |

|||

* {{Cite book |last=Pitre |first=Brant |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=t4EaqOT4nKUC |title=Jesus and the Jewish Roots of the Eucharist: Unlocking the Secrets of the Last Supper |date=2011-02-15 |publisher=Crown Publishing Group |isbn=978-0-385-53185-6 |language=en}} |

|||

*{{cite journal|first=Bargil |last=Pixner|author-link=Bargil Pixner|title=The Church of the Apostles found on Mount Zion|journal= [[Biblical Archaeology Review]] |volume=16|issue=3 |date=May–June 1990 |url=http://www.centuryone.org/apostles.html|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180309011150/http://www.centuryone.org/apostles.html |archive-date=9 March 2018 }} |

|||

*{{cite book | last=Pope | first=Stephen | title=The ethics of Aquinas | publisher=Georgetown University Press | publication-place=Washington, D.C | year=2002 | isbn=0-87840-888-6 | oclc=47838307}} |

|||

*{{Cite web |title=Jesus Didn't Eat a Seder Meal |last1=Poupko |first1=Yehiel |last2=Sandmel |first2=David |work=ChristianityToday.com |date=6 April 2017 |access-date=28 August 2021 |url= https://www.christianitytoday.com/ct/2017/march-web-only/jesus-didnt-eat-seder-meal.html |quote=}} |

|||

*{{cite book | last=Ridderbos | first=Herman | title=The Gospel according to John: a theological commentary | publisher=W.B. Eerdmans Pub | publication-place=Grand Rapids, Mich | year=1997 | isbn=978-0-8028-0453-2 | oclc=36133366|chapter=The Farewell Prayer|author-link=Herman Nicolaas Ridderbos}} |

|||

*{{cite book | last1=Rice | first1=Howard | title=Reformed worship | publisher=Geneva Press | publication-place=Louisville | year=2001 | isbn=0-664-50147-8 | oclc=45363586|first2=James C.|last2= Huffstutler}} |

|||

*{{cite book | last=Riesner | first=R. | translator=D. Stott | title=Paul's Early Period: Chronology, Mission Strategy, Theology | publisher=W.B. Eerdmans | year=1998 | isbn=978-0-8028-4166-7 | url=https://books.google.com/books?id=7mAqa7PYr4kC&pg=PA27 }} |

|||

*{{cite book|last1=Sanders|first1=E. P.|title=The Historical Figure of Jesus|date=1995|publisher=Penguin |isbn=978-0-14-014499-4}} |

|||

*{{cite book | last1=Stakhov | first1=A.P. | last2=Olsen | first2=S.A. | title=The Mathematics of Harmony: From Euclid to Contemporary Mathematics and Computer Science | publisher=World Scientific | series=K & E series on knots and everything | year=2009 | isbn=978-981-277-582-5 | url=https://books.google.com/books?id=uyZpDQAAQBAJ }} |

|||

*{{cite journal|last1=Telford|first1=William R.|title=Review of The Mystery of the Last Supper: Reconstructing the Final Days of Jesus|journal=The Journal of Theological Studies|date=2015|volume=66|issue=1|pages=371–76|doi=10.1093/jts/flv005}} |

|||

*{{cite book | last=Thompson | first=B. | title=Humanists and Reformers: A History of the Renaissance and Reformation | publisher=Wm B. Eerdmans | year=1996 | isbn=978-0-8028-6348-5 | url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Hrq9d567398C&pg=PA493 }} |

|||

*{{cite book|last=Vermes|first= Geza|title=The authentic gospel of Jesus|location= London|publisher= Penguin |date=2004}} |

|||

* {{cite book | last1=Wainwright | first1=G. |author-link=Geoffrey Wainwright | last2=Tucker | first2=K.B.W. |author-link2=Karen B. Westerfield Tucker | title=The Oxford History of Christian Worship | publisher=Oxford University Press, USA | year=2006 | isbn=978-0-19-513886-3 | url=https://books.google.com/books?id=h5VQUdZhx1gC}} |

|||

*{{cite book | last=Wawrykow | first=Joseph | title=The A-Z of Thomas Aquinas | publisher=SCM Press | publication-place=London | year=2005a | isbn=0-334-04012-4 | oclc=61666905}} |

|||

*{{cite book | last=Wawrykow | first=Joseph | title=The Westminster handbook to Thomas Aquinas | publisher=Westminster John Knox Press | publication-place=Louisville, Ky | year=2005b | isbn=978-0-664-22469-1 | oclc=57530148}} |

|||

*{{cite book|url = https://books.google.com/books?id=1UWp5pi1SdUC&pg=PA64 |title = Worship and Festivals|publisher=[[Heinemann (publisher)|Heinemann]]|first1=Gwyneth |last1=Windsor|first2= John |last2=Hughes|date=1990|isbn = 978-0-435-30273-3}} |

|||

* {{Cite book |last=Wright |first=Tom |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=j0fOoAEACAAJ |title=The Meal Jesus Gave Us: Understanding Holy Communion |date=2014 |publisher=SPCK Publishing |isbn=978-0-281-07296-5 |language=en}} |

|||

*{{cite book | last=Yarbrough | first=Robert | title=1-3 John | publisher=Baker Academic | publication-place=Grand Rapids, Mich | year=2008 | isbn=978-0-8010-2687-4 | oclc=225852361}} |

|||

*{{cite book|title=Gospel figures in art|first=Stefano |last=Zuffi|date= 2003|isbn=978-0-89236-727-6|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=tL3YeduAk8gC|publisher=[[J. Paul Getty Museum]]|location= Los Angeles}} |

|||

{{refend}} |

|||

==External links== |

==External links== |

||

{{Commons category}} |

|||

* [http://altreligion.about.com/library/texts/bl_differentdvc.htm A Different Da Vinci Code] The missing pieces of Leonardo's puzzle point to plain and simple [[Hermeticism]] (altreligion.about.com article). |

|||

* [ |

* [https://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/331170/Last-Supper "Last Supper"] on the ''[[Encyclopædia Britannica]]'' Online |

||

* [http://www.abcgallery.com/religion/lastsupper.html The Last Supper interpreted by 7 Artists] |

|||

* [http://www.elrelojdesol.com/interactive-paintings/the-last-supper.html Leonardo da Vinci - The Last Supper (Zoomable Version)] |

|||

* [http://sabbath.org//index.cfm/fuseaction/Library.sa/subj/passover/passover-articles.htm Passover observance for New Covenant Christians] |

|||

* [http://www.geocities.com/christianoriginsoccasionalpapers/ The Soteriologic Significance of the Last Supper] |

|||

*[http://jewishencyclopedia.com/view.jsp?artid=254&letter=J&search=Jesus#1006 Jewish Encyclopedia: Jesus: The Last Supper] |

|||

{{Easter}} |

|||

[[Category:Christian liturgy, rites, and worship services|Last Supper, The]] |

|||

{{Major events in Jesus life}} |

|||

[[Category:Jesus|Last Supper, The]] |

|||

{{Apostles}} |

|||

[[Category:Judeo-Christian topics|Last Supper, The]] |

|||

{{Last Supper in art}} |

|||

[[Category:Luminous Mysteries]] |

|||

{{Authority control}} |

|||

[[Category:Gospel episodes]] |

|||

{{DEFAULTSORT:Last Supper, The}} |

|||

[[de:Abendmahl]] |

|||

[[ |

[[Category:Last Supper| ]] |

||

[[Category:1st century in Jerusalem]] |

|||

[[fr:Cène]] |

|||

[[Category:Christian terminology]] |

|||

[[id:Perjamuan terakhir]] |

|||

[[ |

[[Category:Dining events]] |

||

[[Category:Luminous Mysteries]] |

|||

[[he:הסעודה האחרונה (אירוע)]] |

|||

[[Category:Passion of Jesus]] |

|||

[[nl:Het Laatste Avondmaal (Jezus)]] |

|||

[[Category:Sacraments]] |

|||

[[ja:最後の晩餐]] |

|||

[[pl:Ostatnia Wieczerza]] |

|||

[[pt:A Última Ceia]] |

|||

[[sl:Zadnja večerja]] |

|||

Latest revision as of 12:02, 25 May 2024

The Last Supper is the final meal that, in the Gospel accounts, Jesus shared with his apostles in Jerusalem before his crucifixion.[2] The Last Supper is commemorated by Christians especially on Holy Thursday.[3] The Last Supper provides the scriptural basis for the Eucharist, also known as "Holy Communion" or "The Lord's Supper".[4]

The First Epistle to the Corinthians contains the earliest known mention of the Last Supper. The four canonical gospels state that the Last Supper took place in the week of Passover, days after Jesus's triumphal entry into Jerusalem, and before Jesus was crucified on Good Friday.[5][6] During the meal, Jesus predicts his betrayal by one of the apostles present, and foretells that before the next morning, Peter will thrice deny knowing him.[5][6]

The three Synoptic Gospels and the First Epistle to the Corinthians include the account of the institution of the Eucharist in which Jesus takes bread, breaks it and gives it to those present, saying "This is my body given to you".[5][6] The Gospel of John tells of Jesus washing the feet of the apostles,[7] giving the new commandment "to love one another as I have loved you",[8] and has a detailed farewell discourse by Jesus, calling the apostles who follow his teachings "friends and not servants", as he prepares them for his departure.[9][10][11]

Some scholars have looked to the Last Supper as the source of early Christian Eucharistic traditions.[12][13][14][15][16][17] Others see the account of the Last Supper as derived from 1st-century eucharistic practice as described by Paul in the mid-50s.[13][18][19][20]

Terminology

The term "Last Supper" does not appear in the New Testament,[21][22] but traditionally many Christians refer to such an event.[22] The term "Lord's Supper" refers both to the biblical event and the act of "Holy Communion" and Eucharistic ("thanksgiving") celebration within their liturgy. Evangelical Protestants also use the term "Lord's Supper", but most do not use the terms "Eucharist" or the word "Holy" with the name "Communion".[23]

The Eastern Orthodox use the term "Mystical Supper" which refers both to the biblical event and the act of Eucharistic celebration within liturgy.[24] The Russian Orthodox also use the term "Secret Supper" (Church Slavonic: "Тайная вечеря", Taynaya vecherya).