History of paleontology: Difference between revisions

| Line 43: | Line 43: | ||

In Cuvier's landmark 1796 paper on living and fossil elephants he referred to a single catastrophe that had wiped out a world of life that had existed before the current one. However, as he continued his work on extinct mammals, he came to realize that animals such as [[Palaeotherium]] had lived before the time of the Mammoths and the rest of the fauna that had coexisted with them, and this lead him to write in terms of multiple geological catastrophes, which had wiped out a series of successive faunas.<ref> Rudwick pp. 124-125 </ref> Reinforced by paleobotany, and the dinosaur and marine reptile discoveries in Britain, this view had become the scientific consensus by about 1830. <ref> Rudwick pp. 156-157 </ref> However, in Great Britain, where [[natural theology]] was very influential in the early 19th century, a group of geologists that included Buckland, and [[Robert Jameson]] insisted in explicitly linking the most recent of Cuvier's catastrophes to the biblical flood. This gave the discussion of [[catastrophism]] a religious overtone in Britain that was absent elsewhere.<ref> Rudwick pp. 133-136 </ref> |

In Cuvier's landmark 1796 paper on living and fossil elephants he referred to a single catastrophe that had wiped out a world of life that had existed before the current one. However, as he continued his work on extinct mammals, he came to realize that animals such as [[Palaeotherium]] had lived before the time of the Mammoths and the rest of the fauna that had coexisted with them, and this lead him to write in terms of multiple geological catastrophes, which had wiped out a series of successive faunas.<ref> Rudwick pp. 124-125 </ref> Reinforced by paleobotany, and the dinosaur and marine reptile discoveries in Britain, this view had become the scientific consensus by about 1830. <ref> Rudwick pp. 156-157 </ref> However, in Great Britain, where [[natural theology]] was very influential in the early 19th century, a group of geologists that included Buckland, and [[Robert Jameson]] insisted in explicitly linking the most recent of Cuvier's catastrophes to the biblical flood. This gave the discussion of [[catastrophism]] a religious overtone in Britain that was absent elsewhere.<ref> Rudwick pp. 133-136 </ref> |

||

Partly in response to what he saw as unsound and unscientific speculations by [[William Buckland]] and other practitioners of [[flood geology]], [[Charles Lyell]] advocated the geological theory of [[uniformitarianism]] in his influential work ''Principles of Geology''. <ref> McGowan pp. 93-95 </ref> Lyell amassed a tremendous amount of evidence both from his own field |

Partly in response to what he saw as unsound and unscientific speculations by [[William Buckland]] and other practitioners of [[flood geology]], [[Charles Lyell]] advocated the geological theory of [[uniformitarianism]] in his influential work ''Principles of Geology''. <ref> McGowan pp. 93-95 </ref> Lyell amassed a tremendous amount of evidence both from his own field research and the work of others that showed that rather than depending on past catastrophes most geological features could be better explained by the slow action of present day forces, such as volcanism, earthquakes, erosion, and sedimentation. <ref> McGowan pp. 100-103 </ref> Lyell also claimed that the apparent evidence for catastrophic changes from the fossil record, and even the appearance of progression in the history of life, were illusions caused by imperfections in that record.<ref>McGowan pp. 100-103</ref> As evidence Lyell pointed to the Stonesfield mammal, and to the fact that certain [[Pleistocene]] strata showed a mixture of extinct and still surviving species.<ref> Rudwick pp. 178-181</ref> Lyell had significant success in convincing geologists of the idea that the geological features of the earth were largely due to the action of the same geologic forces that could be observed in the present day acting over an extended period of time. However, he was much less successful in converting people to his view of the fossil record, which he claimed showed no true progression.<ref>McGowan pp. 100</ref> |

||

===Geological time scale and the history of life=== |

===Geological time scale and the history of life=== |

||

Revision as of 02:36, 1 April 2007

The history of paleontology has been an ongoing effort to understand the history of life on Earth by understanding the fossil record left behind by living organisms. Inevitably, it has been closely tied to geology and the effort to understand the history of the Earth itself. In the 17th and 18th centuries, progress was made in understanding the nature of fossils, and the at the end of the 18th century the work of Georges Cuvier lead to the emergence of paleontology, in association with comparative anatomy, as a scientific discipline. The expanding knowledge of the fossil record also played an increasing role in the development of geology, particularly stratigraphy. The first half of the 19th century saw a rapid increase in knowledge about the past history of life on Earth and the progress towards definition of the geologic time scale. After Charles Darwin published the Origin of Species in 1859, much of the focus of paleontology shifted to understanding evolutionary paths, including human evolution, and evolutionary theory. The last half of the 20th century saw a renewed interest in mass extinctions and their role in history of life on Earth. During the past two decades there has been intense interest in fossils from the Cambrian period. This has been part of an effort to understand the Cambrian Explosion during which many new animal forms appeared, including most phyla we recognize today.

Prior to the 17th century

As early as the 6th century BC, Xenophanes of Colophon recognized that some fossil shells were remains of shellfish, and used this to argue that what was now dry land was once under the sea. It is well known that in one of his unpublished notebooks Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519) also concluded that some fossil sea shells were the remains of shellfish. However in both these cases it is clear that the fossils were relatively complete remains of shellfish species that very closely resembled living species. Thus they were relatively easy to classify.[1]

Shen Kuo (Chinese: 沈括) (1031 - 1095) used fossils to infer the existence of geological processes. [2]

As late as the 16th century there was still little recognition that fossils were remains of living organisms. The etymology of the word fossil comes from the Latin for things having been dug up. As this indicates, the term was applied to wide variety of stone and stone like objects without regard to whether they might have an organic origin. 16th century writers such as Conrad Gesner and Georg Agricola were more interested in classifying such objects by their properties, both physical and possibly mystical/medical, than they were in determining the objects origins.[3] One reason that the possibility that fossils might be actual remains of once living organisms was not more widely considered, was that the natural philosophy of the period encouraged alternative explanations. Both the Aristotelian and Neoplatonic schools of philosophy provided intellectual frameworks where it was reasonable to believe that stony objects might grow within the earth to resemble living things. Neoplatonic philosophy maintained that there could be affinities between living and non living objects that could cause one to resemble the other. The Aristotelian school maintained that it was possible for the seeds of living organisms to enter the ground and generate objects that resembled those organisms.[4]

17th century

The 17th century, often referred to as the Age of Reason, saw fundamental changes in natural philosophy that were reflected in the analysis of fossils. In 1665 Robert Hooke published Micrographia, an illustrated collection of his observations with a microscope. One of these observations was entitled Of Petrify'd wood, and other Petrify'd bodies, which included a comparison between petrified wood and ordinary wood. He concluded that petrified wood was ordinary wood that had been soaked with "water impregnated with stony and earthy particles". He then went on to suggest that several kinds of fossil sea shells were formed from ordinary shells by a similar process. He argued against the prevalent view that such objects were "Stones form'd by some extraordinary Plastick virtue latent in the Earth itself".[5]

In 1667 Nicholas Steno wrote a paper on a large shark head he had dissected the year before, in which he compared the teeth of the shark with the common fossil objects known as tongue stones. He concluded that the fossils must have been shark teeth. This caused Steno to take an interest in the question of fossils and to address some of the objections that were raised against their organic origin. As a result he did some geological research and in 1669 published Forerunner to a Dissertation on a solid naturally enclosed in a solid. In that work Steno drew a clear distinction between objects such as rock crystals that really were formed within rocks and objects such as fossil shells and shark teeth that were formed outside of the rocks they were found in. Steno realized that certain kinds of rock had been formed by the successive deposition of horizontal layers of sediment and that fossils were the remains of living organisms that had become buried in that sediment. Steno who, like almost all 17th century natural philosophers, believed that the earth was only a few thousand years old, resorted to the Biblical flood as a possible explanation for fossils of marine organism that were found very far from the sea.[6]

Despite the considerable influence of Forerunner, naturalists such as Martin Lister (1638-1712) and John Ray (1627-1705) continued to question the organic origin of some fossils. They were particularly concerned about objects such as fossil Ammonites, which Hooke had claimed were organic in origin, which did not closely resemble any known living species. This raised the possibility of extinction, which they found difficult to accept for philosophical and theological reasons.[7]

18th century

In his 1778 work Epochs of Nature Georges Buffon referred to fossils, in particular the discovery of what he thought of as fossils of tropical species such as elephants and rhinoceros in northern Europe, as evidence for the theory that the earth had started out much warmer than it currently was and had been gradually cooling.

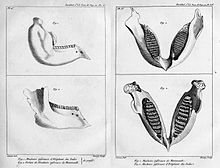

In 1796 Georges Cuvier presented a paper on living and fossil elephants, in which he used comparative anatomy to analyze skeletal remains of Indian and African elephants, mammoth fossils, and fossil remains of an animal recently found in North America that he would later name mastodon. He established for the first time that Indian and African elephants were different species, and even more importantly that mammoths had been a different species from either and therefore must be extinct. He further concluded that the mastodon must be another extinct species that was even more different from Indian or African elephants than mammoths had been. Cuvier’s ground breaking work in paleontology and comparative anatomy, lead to the wide spread acceptance of the reality of extinction.[8] It also lead Cuvier to advocate the geological theory of catastrophism to explain the succession of living things revealed by the fossil record. Cuvier also pointed out that since mammoths and wooly rhinoceros were not the same species as the elephants and rhinoceros currently living in the tropics, their fossils could not be used as evidence for a cooling earth. Cuvier made another powerful demonstration of the power of comparative anatomy in paleontologhy when he presented a second paper in 1796 on a large fossil skeleton from Paraguay, which he named Megatherium and identified as a giant sloth by comparing its skull to those of two living species of tree sloth.

In a pioneering application of stratigraphy, the study of the layering of rocks, William Smith, a surveyor and mining engineer, made extensive use of fossils to help correlate rock strata in different locations as he worked on the first geological map of England during the late 1790s and early 1800s. In the process he established the principle of faunal succession, the idea that each strata of sedimentary rock would contain particular types of fossis, and that these would succeed one another in a predictable way even in widely separated geologic formations. Cuvier and Alexandre Brongniart, an instructor at the Paris school of mine engineering, used similar methods during the same period in an influential study of the geology of the region around Paris.

First half of the 19th century

The age of reptiles

Cuvier in 1808 identified a fossil found in Maastricht as a giant marine reptile that he named Mosasaurus. He also identified, from a drawing, another fossil found in Bavaria as a flying reptile and named it Pterodactylus. He speculated that an age of reptiles had preceded the first mammals.[9]

Cuvier's speculation would be supported by a series of spectacular finds that would be made in Great Britain over the course of the next couple of decades. Mary Anning, a professional fossil collector since age 11, collected the fossils of a number of marine reptiles from the Jurassic marine strata at Lyme Regis. These included the first ichthyosaur skeleton to be recognized as such, which was collected in 1811, and the first plesiosaur collected in 1821. Many of her discoveries would be described scientifically by the geologists William Conybeare, Henry De la Beche and William Buckland.[10]

In 1824 Buckland found and described a lower jaw from Jurassic deposits from Stonesfield. He deemed the bone to have belonged to a giant carnivorous land dwelling reptile he called Megalosaurus. That same year Gideon Mantell realized that some large teeth he had found in 1822, in Cretaceous rocks from Tilgate, belonged to a giant herbivorous land dwelling reptile. He called it Iguanodon, because the teeth resembled those of an iguana. In 1832 Mantell would find a partial skelton of an armoured reptile he would call Hylaeosaurus in Tilgate. In 1842 the English anatomist Richard Owen would create a new order of reptiles, that he called Dinosauria for Megalosaurus, Iguanodon and Hylaeosaurus. [11]

This growing evidence that an age of giant reptiles had preceded the age of mammals caused great excitement in scientific circles[12], and even among some segments of the general public[13]. Buckland did describe the jaw of a small primitive mammal, Phascolotherium, that was found in the same strata as Megalosaurus. This discovery, known as the Stonesfield mammal, was a much discussed anomaly. Cuvier at first thought it was a Marsupial, but Buckland later realized it was a primitive Placental mammal. Due to its small size and primitive nature, Buckland did not believe it invalidated the overall pattern of an age of reptiles preceding the age of mammals. [14]

Paleobotany

In 1828 Alexandre Brongniart's son the botanist Adolphe Brongniart published the introduction to a longer work on the history of fossil plants. Adolphe Brongniart concluded that the history of plants could roughly be divided into four parts. The first period was characterized by cryptogams. The second period was characterized by the appearance of the first conifers. The third period saw the emergence of the cycads, and the forth by the emergence of the flowering plants (such as the dicotyledons). The transitions between each of these periods was marked by sharp discontinuities in the fossil reccord, with more gradual changes within each of the periods. Besides being foundational to paleobotany Brongniart's work strongly reinforced the impression that was emerging from both vertebrate and invertebrate paleontology that life on earth had a progressive history with different groups of plants and animals making their appearances in some kind of successive order. [15]

Catastrophism, uniformitarianism and the fossil record

In Cuvier's landmark 1796 paper on living and fossil elephants he referred to a single catastrophe that had wiped out a world of life that had existed before the current one. However, as he continued his work on extinct mammals, he came to realize that animals such as Palaeotherium had lived before the time of the Mammoths and the rest of the fauna that had coexisted with them, and this lead him to write in terms of multiple geological catastrophes, which had wiped out a series of successive faunas.[16] Reinforced by paleobotany, and the dinosaur and marine reptile discoveries in Britain, this view had become the scientific consensus by about 1830. [17] However, in Great Britain, where natural theology was very influential in the early 19th century, a group of geologists that included Buckland, and Robert Jameson insisted in explicitly linking the most recent of Cuvier's catastrophes to the biblical flood. This gave the discussion of catastrophism a religious overtone in Britain that was absent elsewhere.[18]

Partly in response to what he saw as unsound and unscientific speculations by William Buckland and other practitioners of flood geology, Charles Lyell advocated the geological theory of uniformitarianism in his influential work Principles of Geology. [19] Lyell amassed a tremendous amount of evidence both from his own field research and the work of others that showed that rather than depending on past catastrophes most geological features could be better explained by the slow action of present day forces, such as volcanism, earthquakes, erosion, and sedimentation. [20] Lyell also claimed that the apparent evidence for catastrophic changes from the fossil record, and even the appearance of progression in the history of life, were illusions caused by imperfections in that record.[21] As evidence Lyell pointed to the Stonesfield mammal, and to the fact that certain Pleistocene strata showed a mixture of extinct and still surviving species.[22] Lyell had significant success in convincing geologists of the idea that the geological features of the earth were largely due to the action of the same geologic forces that could be observed in the present day acting over an extended period of time. However, he was much less successful in converting people to his view of the fossil record, which he claimed showed no true progression.[23]

Geological time scale and the history of life

Geologists such as Adam Sedgwick, and Roderick Murchison continued, despite some contentious disputes, making great advances in stratigraphy as they described new geological epochs such as the Cambrian, the Silurian, the Devonian, and the Permian. By the early 1840s much of the geologic timescale had taken shape. All three of the periods of the Mesozoic era and all the periods of the Paleozoic era except the Ordovician had been defined.[24] It remained a relative time scale with no method of assigning any of the periods absolute dates. It was understood that not only had there been an age of reptiles preceding the age of mammals, but there had a time (during the Cambrian and the Silurian) when life had been restricted to the sea, and a time (prior to the Devonian) when invertebrates had been the dominant form of animal life.

2nd half of the 19th century

Evolution

Charles Darwin's publication of the Origin of Species in 1859 and the resulting scientific debate lead to an effort to look for transitional fossils and other evidence of evolution in the fossil record. There were two areas where early success attracted considerable attention, the transition between reptiles and birds, and the evolution of the modern single toed horse.[25] In 1861 the first specimen of Archaeopteryx, an animal with both teeth and feathers and a mix of other reptilian and avian features, was discovered in a limestone quarry in Bavaria and another would be found in 1881. Other primitive toothed birds were found by Othniel Marsh in Kansas in 1872. Marsh also discovered fossils of several primitive horses in the Western United States that helped trace the evolution of the horse from the small 5 toed Hyracotherium of the Eocene to the much larger single toed modern horses of the genus Equus. Thomas Huxley would make extensive use of both the horse and bird fossils in his advocacy for evolution.

There was also great interest in human evolution. Neanderthal fossils were discovered in 1856, but at the time it was not clear that they represented a different species from modern humans. Eugene Dubois created a sensation with his discovery of Java Man, the first fossil evidence of a species that seemed clearly intermediate between humans and apes, in 1891.

Developments in North America

In the 2nd half of the 19th century saw a rapid expansion of paleontology in North America. In 1858 Joseph Leidy described a Hadrosaurus skeleton, which was the first North American dinosaur to be described from good remains. However, it was the massive westward expansion of railroads, military bases, and settlements into Kansas and other parts of the Western United States following the American Civil War that really fueled the expansion of fossil collection.[26] The result was an increased understanding of the natural history of north America, including the discovery of the Western Interior Sea that had covered Kansas and much of the rest of the Midwestern United States during parts of the Cretaceous, the discovery several important fossils of primitive birds and horses, and the discovery of a number of new dinosaur species including Allosaurus, Stegosaurus, and Triceratops. Much of this activity was part of a fierce personal and professional rivalry between 2 men, Othniel Marsh, and Edward Cope, which has become known as the Bone Wars.

Some developments in the 20th century

Developments in geology

Two 20th century developments in geology had a big effect on paleontology. The first was the development of radiometric dating which allowed absolute dates to be assigned to the geologic timescale. The 2nd was the theory of plate tectonics, which helped make sense of the geographical distribution of ancient life.

Mass extinctions

The 20th century saw a major renewal of interest in mass extinction events and their effect on the course of the history of life. This was particularly true after 1980 when Luis and Walter Alvarez put forward the Alvarez hypothesis claiming that an impact event caused the Cretaceous-Tertiary extinction, which killed off the dinosaurs along with many other living things.

Evolutionary paths and theory

Throughout the 20th century new fossil finds continued to contribute to understanding the paths taken by evolution. Examples include major taxonomic transitions such as finds in Greenland, starting in the 1930’s (with more major finds in the 1980’s), of fossils illustrating the evolution of tetrapods from fish, and finds in China during the 1990s that shed light on the dinosaur-bird connection. Other events that have attracted considerable attention have included a series of finds in Pakistan that have shed light on whale evolution, and most famously of all a series of finds throughout the 20th century in Africa (starting with Taung child in 1924) and elsewhere have helped illuminate the course of human evolution. Increasingly at the end of the century the results of paleontology and molecular biology were being correlated to reveal phylogenic trees. The results of paleontology have also contributed to other areas of evolutionary theory such as the theory of punctuated equilibrium.

Cambrian explosion

One areas of paleontology that has seen a lot of activity during the 1980’s, 1990’s and beyond is the study of the Cambrian explosion during which the various phyla of animals with their distinctive body plans first appear. The well known Burgess Shale Cambrian fossil site was found in 1909 by Charles Doolittle Walcott, and another important site in Chengjiang China was found in 1912. However, new analysis in the 1980s by Harry B. Whittington, Derek Briggs, Simon Conway Morris and others sparked a renewed interest and a burst of activity including discovery of an important new fossil site, Sirius Passet, in Greenland, and the publication of a popular and controversial book, Wonderful Life by Stephen Jay Gould in 1989.

See also

- History of biology

- History of geology

- History of science

- List of fossil sites (with link directory)

Notes

- ^ Rudwick The Meaning of Fossils pp 39

- ^ Shen Kuo,Meng Xi Bi Tan (梦溪笔谈; Dream Pool Essays) (1088)

- ^ Rudwick pp 23-33

- ^ Rudwick pp 33-36

- ^ Hooke Micrographia observation XVII

- ^ Rudwick pp 72-73

- ^ Rudwick pp 61-65

- ^ McGowan the dragon seekers pp 3-4

- ^ Rudwick Georges Cuvier, Fossil Bones and Geological Catastrophes pp 158

- ^ McGowan pp 11-27

- ^ McGowan pp 176

- ^ McGowan pp 70-87

- ^ McGowan pp 109

- ^ McGowan pp. 78-79

- ^ Rudwick pp. 145-147

- ^ Rudwick pp. 124-125

- ^ Rudwick pp. 156-157

- ^ Rudwick pp. 133-136

- ^ McGowan pp. 93-95

- ^ McGowan pp. 100-103

- ^ McGowan pp. 100-103

- ^ Rudwick pp. 178-181

- ^ McGowan pp. 100

- ^ Rudwick The Meaning of Fossils pp 213

- ^ Larson Evolution pp 139

- ^ Everhart Oceans of Kansas pp 17

References

- Rudwick, Martin J.S. The Meaning of Fossils. The University of Chicago Press: Chicago 1972. ISBN 0-226-73103-0

- McGowan, Christopher The Dragon Seekers. Persus Publishing: Cambridge MA 2001. ISBN 0-7382-0282-7

- Rudwick, Martin J.S. Georges Cuvier, Fossil Bones, and Geological Catastrophes (The University of Chicago Press, 1997)ISBN 0-226-73106-5

- Robert Hooke Micrographia The Royal Society 1665

- Larson, Edward J. Evolution: The Remarkable History of a Scientific Theory. The Modern Library: New York, 2004. ISBN 0-679-64288-9

- Michael J. Everhart Oceans of Kansas: A Natural History of the Western Interior Sea. Indiana University Press: Bloomington, IN, 2005. ISBN 0-253-34547-2