Bavaria

The Bavaria (the Latinized expression for Bayern is) the female symbol shape and secular saint of Bavaria, acting as personified allegory on the state structure Bayern in different forms and manifestations. She thus represents the secular counterpart to Maria as the religious patrona Bavariae .

In the visual arts, the colossal bronze statue in Munich can be considered the most famous and at the same time the most monumental representation of Bavaria. It was built on behalf of King Ludwig I (1786–1868) in the years 1843 to 1850 and is a structural unit with the Hall of Fame on the edge of the slope above the Theresienwiese .

After the baroque colossal statues of the 17th century , it is the first example of its kind from the 19th century and, since ancient times, the first colossal statue made entirely of cast bronze . It was and is a technical masterpiece.

Allegories of Bavaria

The Tellus Bavarica is an allegory of the “Bavarian earth” that has been in use for many centuries. It comes in many forms, including coats of arms , paintings , reliefs , for example above house entrances, and as a statue. In the public perception, Bavaria is largely identified today with the monumental statue on Theresienwiese, but other examples can be found in public space. An easily accessible one can be seen in the Munich court garden : the dome of the central " Diana temple " was originally crowned by a bronze statue of Diana by Hubert Gerhard , which Hans Krumpper presumably transformed into an allegory of Bavaria in 1623 by adding an electoral hat to her helmet and an orb instead of a wreath of ears. Today there is a copy on the temple, the original is on display in the Theatinergang of the Munich residence .

In 1773 Bartolomeo Altomonte created parts of the baroque design of the Fürstenzell monastery near Passau and placed the Bavaria in the center of the ceiling fresco in the Fürstensaal. She is represented as queen at the moment of her coronation by an angel and is surrounded by allegories of the church, trade, agriculture and the arts.

A completely different version of a Bavarian national allegory was created by the artist Marianne Kurzinger in her oil painting "Gallia protects Bavaria" in 1805 . The picture shows a girlish, delicate allegory of the country in a white and blue robe, which takes refuge from the impending storm in the arms of the approaching Gallia , while the Bavarian lion throws itself against the disaster. The representation reflects the alliance between Bavaria and France at that time. The Habsburg Emperor Franz had threatened: "I will not take Bavaria, I will devour it."

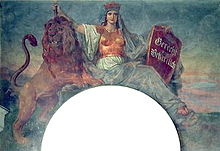

Around a quarter of a century later, Peter von Cornelius, together with other artists involved in the design of the Munich Hofgartenarkaden , created a much more self-confident allegory of Bavaria as a fresco: This peaceful but defensive Bavaria wears a harness and a wall crown , with her right hand she holds an inverted spear than Peace sign , in the left a sign with the motto of King Ludwig I “Just and persevering”. With the Bavarian lion at her side, she sits in front of a landscape of mountains and river valleys.

Schwanthaler's work on the colossal sculpture for the Hall of Fame, which was already quite advanced at that time, was almost certainly known to the unknown painter of a Tölz shooting target from 1851 from the press or even from his own experience: although freely interpreted, his depiction of Bavaria shows this but with the same attributes as the two years later, Bavaria unveiled an der Theresienwiese. The clothing is different, but the position on the pedestal, the sword in the right hand and the victory wreath in the left clearly show the model. However, the artist placed the allegory here in front of an Alpine landscape with a city view of Bad Tölz in the background and added a city coat of arms in the foreground.

From 2011 to 2018 the Bavaria, portrayed by the actress Luise Kinseher , gave the fasting sermon at the strong beer tap on the Nockherberg .

Hall of Fame and Bavaria

The Bavaria at Theresienwiese is framed by the Hall of Fame and the Bavariapark . It forms a conceptual and creative unit, albeit with breaks, with the three-winged Doric columned hall surrounding it, which it towers above on its base. Therefore, the description of the Bavaria is preceded by a brief description of the history of the hall below. A more detailed description of the development can be found in the article about the Munich Hall of Fame .

History of the origin of the hall of fame

Historical background

The youth of Ludwig I was shaped by Napoleon's claims to power on the one hand and Austria on the other. At that time , the Wittelsbach family was a plaything between the two great powers. Until 1805, when Napoleon "liberated" Munich in the third coalition war and made Ludwig's father Maximilian king, Bavaria was repeatedly a theater of war with devastating consequences for the country. Only with Napoleon's defeat in the Battle of Leipzig in 1813 did Bavaria really enter a phase of peace.

Against this background, Crown Prince Ludwig thought about a "Baiern of all tribes" and a "larger German nation". These motives and goals motivated him in the following years to several construction projects for national monuments such as the Constitution Column in Gaibach (1828), the Walhalla east of Regensburg above the Danube and the town Donaustauf (1842), the Hall of Fame in Munich (1853) and the Liberation Hall in Kelheim (1863), all of which the King financed privately and which, in terms of form and content, purpose and reception, form an artistic and political unit that is unique for Germany despite all internal contradictions.

Ludwig, who succeeded his father to the royal throne after his death in 1825, felt closely connected to Greece, was an ardent admirer of ancient Greece and wanted to transform his capital Munich into an "Isar Athens". Ludwig's second-born son Otto was proclaimed King of Greece in 1832 .

Building history

As Crown Prince Ludwig developed the plan to erect a patriotic monument in the royal seat of Munich, in the following years he had lists and registers of "great" Bavarians of all classes and professions made. In 1833 he announced a competition for his building project. The competition was initially intended to collect initial ideas for the design of the Hall of Fame, which is why only the key project data were given in the tender: The hall should be built above the Theresienwiese and offer space for around 200 busts. The only requirement was:

This provision did not rule out the classicist architectural style of the parallel Walhalla project, but it seems reasonable to assume that the architects should be encouraged to propose a different architectural style. Since the designs of the four participants have largely been preserved, there is an interesting insight into the building history of the Hall of Fame, which arose in a phase of artistic and ideological dispute between classicists on the one hand, who felt connected to the aesthetics of Greek and Roman antiquity , and romantics on the other, who based their artistic expression on the formal language of the Middle Ages . In the competition for the Hall of Fame, this was not only a continuation of the artistic-architectural, but also ideological and political debate, which is reflected in the submitted designs. Finally, in March 1834, Ludwig I decided against the projects of Friedrich von Gärtner , Joseph Daniel Ohlmüller and Friedrich Ziebland, primarily for cost reasons, and commissioned Leo von Klenze with the construction of the Hall of Fame. Undoubtedly, the colossal statue particularly impressed him about Klenze's design, as such a large sculpture had not been realized since ancient times. Flattered by the idea of erecting statues as imposing as the admired ancient rulers, Ludwig I wrote after his decision in favor of Klenze's design:

" Nero and I are the only ones who have done such great things since Nero hasn't."

The Bavaria

iconography

The statue was originally sketched in antique iconography, but the character was changed during the planning period. The statue that was finally realized is shaped by Romanticism and takes up the symbolism of the Germanic area.

Designs by Leo von Klenze

As early as 1824, von Klenze drew the first drafts of a Bavaria as a "Greek Amazon ". The inspiration for such a statue was the colossal bronze statue of Athena Promachos , several paintings from 1846 show Klenze's idea of the Acropolis of Athens.

After the competition for the design of the hall of fame in favor of v. Klenzes decided, he drew detailed sketches for the hall and other designs for the Bavaria. The sketches show a Bavaria modeled on ancient Amazons with a double-belted dress ( chiton ) and laced sandals . With her right hand she crowns a herm with several heads , the four faces of which are supposed to symbolize the virtues of rulership and warfare, the arts and science. In her left hand, Bavaria holds a wreath at hip height with an outstretched arm, which she symbolically donates to the honored personalities. A lion crouches to the left of the Bavaria.

With this proposal, v. Klenze created a new type of country allegiance by mixing different motifs. As described above, personifications of Bavaria existed long before. But while, for example, the attributes of the Tellus Bavarica on the Hofgarten Temple stand for material riches in the country, v. Dress up his Bavaria with attributes of education and governance. At the same time he drew a new ideal of the state. In v. Klenze's design focuses on a virtuous and enlightened state ideal and displaces the agricultural symbols. In another design from 1834, v. Klenze the Bavaria as an exact copy of Athena Promachos , which once stood in front of the Acropolis. According to this proposal, the Bavaria would have been equipped with a helmet and shield and a raised lance.

On May 28, 1837, the contract for the manufacture of the Bavaria between Ludwig I, v. Klenze, the sculptor Ludwig Schwanthaler and the ore caster Johann Baptist Stiglmaier and his nephew Ferdinand von Miller . The designs for Hermann monuments in the Teutoburg Forest from the 20s of the 19th century, which were only realized after Bavaria, were certainly known to Ludwig I and the artists involved.

Schwanthaler's designs

In contrast to Klenze, who dealt intensively with antiquity , Schwanthaler was a supporter of the romantic movement and belonged to several Munich medieval circles, which were enthusiastic about everything "patriotic", foreign and especially antiquity. That is why Schwanthaler stood in opposition to Klenze's classicist guidelines. Apparently it was part of Ludwig's strategy to incorporate the opposing conceptions of art into the design of the same patriotic monument project in order to unite the divided camps under the roof of the nation. His attempt to synthesize the classical and the romantic-Gothic styles is often referred to in literature as "romantic classicism" or " Ludovician style".

In his first Bavaria designs, Schwanthaler initially followed Klenze's specifications. Soon, however, the sculptor began to design his own variations of the Bavaria. The decisive factor was his decision to no longer design the Bavaria based on the ancient model, but to dress it "Germanic": The shirt-like dress that reached to the feet was now very simply draped and girded together with a bearskin thrown over it, according to the figure Schwanthaler's view gave it a typically "German" character.

In a plaster model from 1840, Schwanthaler went one step further. He now adorned Bavaria's main hair with a wreath of oak . The wreath in the raised left hand, which Klenze made of laurel , also became an oak wreath. The oak was considered a special German tree. The redesign of the Bavaria took place at the same time as the so-called Rhine crisis of 1840/41 and thus in a time of patriotic upsurges against the "archenemy" France. For Schwanthaler, who was already an enthusiastic patriot, this crisis seems to have been the reason to portray his Bavaria with a drawn sword in an emphatically defensive manner. Until 1843, Schwanthaler changed the plaster model, which was constantly being adapted. The initially stiff depiction received “inner movement” and “it was possible to give the compact colossal statue, with its carefully suggested counter-posture, lightness and a relaxed posture. The now inclined head with milder, girlish features exudes a quiet dreaminess that was missing before. The sword is no longer held up in an unnaturally steep angle, but is held at an angle with the right arm bent. The lion is more restless and keeps its mouth closed. "

The attributes of Bavaria, as shown in the case of the bearskin, the oak wreath and the sword, are relatively easy to explain from the art-historical and political context of the history of its creation. However, this is more difficult with the interpretation of the lion . To interpret the animal simply as a symbol for Bavaria is obvious, but does not quite meet the intentions of Klenze and Schwanthaler. In the field of heraldry , the lion has always had a fixed place for the rulers of Bavaria. As Count Palatine near the Rhine, the Wittelsbachers had him in their coat of arms since the High Middle Ages . In addition, two upright lions served as shield holders for the Bavarian coat of arms very early on .

However, the art historian Manfred F. Fischer is of the opinion that the lion, alongside the Bavaria, was not only intended as a heraldic animal of Bavaria, but, like the drawn sword, must be viewed as a symbol of defensibility.

The most important attribute of the Bavaria, however, remains the oak wreath in her left hand. The wreath means a gift of honor for those whose busts should be placed inside the hall of fame.

execution

The 18.52 meter high and 1560 (Bavarian) hundredweight (approx. 87.36 tons) statue of Bavaria was made in bronze and consists of four cast parts (head, chest, hip, lower half and lion) and various assembled ones Small parts. The height of the stone base is 8.92 meters.

According to the suggestions of v. Klenzes are cast in bronze. Bronze has been a venerable and durable material since ancient times. Ludwig, who wanted to receive the evidence of his work for posterity, was very interested in the art of bronze casting. Therefore, the king promoted the Munich bronze caster Johann Baptist Stiglmaier and his nephew Ferdinand von Miller and revived the long tradition of bronze casting in Munich by building a new casting facility. In 1825, the commissioned by Ludwig and v. Klenze's royal ore foundry on Nymphenburger Strasse went into operation. In addition to many other large bronze sculptures from that period, the production of this foundry includes the obelisk on Munich's Karolinenplatz .

Since the end of 1839, Schwanthaler and a number of unskilled workers gradually worked on a plaster model of the Bavaria in original size on the site of the ore foundry. Several workshop halls caught fire during the burning process. In 1840 a first four meter high auxiliary model was made. In the late summer of 1843, the completed, full-size model could then be dismantled into individual parts, which Stiglmaier and Miller then used as a template for the respective molds. Before casting could begin, however, Stiglmaier died in April 1844, and the management of the project went to v. Miller over.

On September 11, 1844, the head of Bavaria was cast from the bronze of Turkish cannons, which sank with the Egyptian-Turkish fleet in the Greek War of Liberation in 1827 in the Battle of Navarino (today Pylos in the Peloponnese ) and under the Greek King Otto, son Ludwig I, had been lifted and sold as recycling material in Europe, many of which ended up in Bavaria. The arms were cast in January and March 1845, and the chest piece on October 11, 1845. The following year the waist was cast, and by July 1848 the entire top of the statue was completed. The last larger cast, for the lower part, took place on December 1, 1849.

The Munich Erzgießereistraße and the parallel sand street on which the sand pit necessary for the casting was located still remind us of the place where the monumental statue was made.

financing

Like all of Ludwig's national monuments, the Bavaria and the Hall of Fame were private projects of the king, which he financed personally. On March 20, 1848, Ludwig I abdicated under pressure in favor of his son Maximilian , which was not without consequences for the continuation of the monument project. Maximilian undertook to continue the company, but his budget for this was only 9,000 guilders per year, which was completely inadequate.

v. Miller, who had to advance the casting costs out of pocket, ran into serious financial difficulties. It was only when the abdicated king took over the financing from his private box that the completion of the Bavaria could be secured. v. Miller was left with some of the costs, but the advertising effect for the ore foundry was so great that the costs were amply offset by a large number of orders and the ore foundry, which was later privatized, was able to hold its own until the 1930s.

In total, the Hall of Fame cost the king 614,987 guilders, Bavaria 286,346 guilders and the property 13,784 guilders.

Installation and inauguration in 1850

For the Oktoberfest in 1850, which would have been the 25th year of Ludwig's reign, the Bavaria was to be unveiled in a festive act. Before the celebration for the abdicated king, concerns of the government had to be dispelled, which feared that such an event could be viewed as a demonstration against the reigning King Maximilian II.

From June to August, the individual parts of the Bavaria were transported to the installation site on specially constructed wagons, each pulled by twelve horses. On August 7, 1850, the head was the last to be guided through the city to Theresienhöhe with a pageant. The solemn unveiling finally took place on October 9th after a pageant of all trades and guilds to Theresienwiese and, as expected, turned into a celebration of homage for the abdicated king. The artists, whom the king had given great support during the years of his reign and supplied with commissions through his brisk building activity, paid special tribute to Ludwig. The keynote speaker Tischlein, speaking for the Munich artist community, called out in his celebratory speech after the unveiling of the Bavaria:

"Thanks and praise for the present, posterity, - Bavaria's bronze oak crown is due above all to King Ludwig the art protector!"

When the Bavaria was unveiled, the Hall of Fame was not yet completed; scaffolding and wooden roofs still covered large parts of the building. It was not until 1853 that the building could be inaugurated as part of a much simpler celebration.

Inside the statue, a spiral staircase leads into the head to a platform with two bronze benches and four viewing hatches. In 2016, 20,635 visitors climbed the statue. The installation of the statue on the slope edge above the then much larger Theresienwiese points beyond the ancient references, where statues and columns related to architecture, but takes up Germanic, romantic motifs: “The expanse of free, limitless space opens up in front of it . It belongs to the flat landscape, not to the architecture ”and“ With the ›Bavaria‹ Schwanthaler succeeded in creating the first monumental romantic work that is self-contained and yet related to the open landscape. ”In the development of the eastern part planned from the 1870s Theresienwiese submitted a draft to Georg von Hauberrisser in 1878, which envisages an oval delimitation of the remaining open space, with all roads flowing radially towards the Bavaria. This concept was taken up and implemented in the building line plan from 1882.

Refill of the right hand

In 1907, Oskar von Miller , Ferdinand von Miller's son and founder of the Deutsches Museum in Munich, ordered a replica of the Bavaria's right hand that was true to the original. It was made in the royal ore foundry Ferdinand von Miller, from the same material as the original (92% copper , 5% zinc , 2% tin , 1% lead ). The cast has a wall thickness of 4 to 8 millimeters and weighs 420 kilograms. Since then, the hand can be viewed in the Metallurgy Collection of the Deutsches Museum.

Redevelopment

The examinations of Bavaria by experts, initiated by the Bavaria 2000 association , brought to light such serious damage that the statue had to be closed to visitors in 2001. In total, over two thousand individual damages were found.

To partially finance the renovation work, the association issued replicas of the only Schwanthaler model, the tip of the statue's little finger, in various scales, including as a drinking vessel, and other handicraft rarities, which were sold together with a publication. As a further source of finance, the outside of the scaffolding was later marketed as advertising space.

In the course of the renovation work , which cost around one million euros, which was immediately initiated , not only was the raised arm carefully stabilized and the entire outer surface cleaned, sanded and sealed , but a completely new spiral staircase was also installed. Work on the statue lasted until the beginning of the Oktoberfest in September 2002. The base of the statue is still in need of renovation.

The Bavaria 2000 association , which under its presidents Adi Thurner and later Erwin Schneider († 2005) had campaigned for the memory of King Ludwig I and the preservation of his buildings and monuments, was dissolved in 2006.

Dealing with the ensemble during the National Socialist era

The National Socialists showed an ambivalent and cynical relationship to the Hall of Fame and Bavaria.

On the one hand, they developed various plans for the redesign of the festival area on Theresienwiese, including the Bavaria and the Hall of Fame, which lack any respect for the location and the intention of the builder. In 1934, a demolition of the Hall of Fame behind the Bavaria was considered, instead an event site was to be built there, and the Theresienwiese should be criss-crossed by parade streets. In 1935 a further plan was presented which provided for the removal of the Bavaria as well as the Hall of Fame in order to build a huge congress hall with a memorial for heroes in its place. According to plans from 1938, the Bavaria and the Hall of Fame were to remain, but be framed by monumental buildings in neoclassical style . They wanted to square the Theresienwiese.

On the other hand, the open area of the Theresienwiese and the existing representative and symbol robust architecture was often used for propaganda productions, for example for mass events in until the outbreak of war grandly celebrated May Day rallies , as the following excerpt from a report by the conformist press testifies about the celebrations on May 1, 1934 :

“In the meantime, the enormous march to the afternoon rally on Theresienwiese began. As early as 1 p.m., the march into nine giant columns took place. 180,000 people poured radially out of the city onto the Theresienwiese. A particularly poignant picture was the approach of ten thousand members of the Nazi war victims' pension . Mayor Fiehler personally led the giant columns of the municipal companies . After 2 p.m., hundreds of flags of the civil associations, which were grouped in the open square of the hall of fame, marched in. Half an hour later the subject Chargierten all student corporations Munich universities one with their banners to take at the foot of the pillars of the Hall of Fame lineup. The immediate introduction of solid rally made at 15 o'clock the invasion of NSBO which NSKBO and student councils . Labor service preceded the procession with a shouldered spade. The flags were placed on the outside staircase to the Bavaria and on its base. The actual rally opened with a speech by the Gauleiter and Minister of State Adolf Wagner, who was received with lively calls of healing . "

Movie

- King Ludwig I and his Bavaria, a film by Bernhard Graf , Bayerischer Rundfunk, 2018.

literature

- Frank Otten: The Bavaria. In: Hans-Ernst Mittig, Volker Plagemann : Monuments in the 19th century (= studies on the art of the 19th century. Vol. 20). Prestel, Munich 1972, ISBN 3-7913-0349-X , pp. 107-112.

- Paul Ernst Rattelmüller : The Bavaria. History of a symbol. Hugendubel, Munich 1977, ISBN 3-88034-018-8

- Helmut Scharf: National monument and national question in Germany using the example of the monuments to Ludwig I of Bavaria and their reception. Schnelldruckzentrum, Gießen 1985 DNB 860622185 (partial print of: Dissertation University of Frankfurt am Main, 1978, 562 pages).

- Christian Gruber, Christoph Hölz: ore time. Ferdinand von Miller - for the 150th birthday of Bavaria. HypoVereinsbank, Munich 1999, ISBN 3-930184-21-4 .

- Manfred F. Fischer: Hall of Fame and Bavaria. Official leader. Revised by Sabine Heym. 2nd expanded edition. Bavarian Administration of State Palaces, Gardens and Lakes, Munich 1997, ISBN 3-9805654-3-2 .

- Ulrike Kretschmar: Bavaria's little finger. History of the creation of Bavaria by Ludwig von Schwanthaler on the occasion of the edition “The little finger of Bavaria” (bronze reproduction). Huber, Offenbach am Main 1990, ISBN 3-921785-53-7 .

- Josef Anselm Pangkofer: Bavaria, giant statue made of ore in front of the Hall of Fame on Theresienwiese near Munich , Franz, Munich 1850, digitized

Web links

- Bavarian palace administration for Bavaria

Individual evidence

- ^ Lars Olaf Larsson: Tellus Bavarica - Metamorphoses of a country allegory . In: Der Münchner Hofgarten - Contributions to a search for traces . Süddeutscher Verlag 1988, ISBN 3-7991-6417-0 , pp. 50-55

- ↑ Bavarian Palace Administration: Hofgarten

- ^ House of Bavarian History: Gallia protects Bavaria , catalog of the 1999 state exhibition "Bavaria and Prussia"

- ↑ Peter von Cornelius et al. (1829): "Allegory of Bavaria" (PDF file; 4.69 MB) Holger Schulten

- ↑ unknown artist (1851): "Allegory of Bavaria with sword, wreath and lion, in front of it the coat of arms of Bad Tölz (?)" ( Memento of the original from March 10, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. House of Bavarian History, Augsburg

- ↑ Surprising announcement on stage: Luise Kinseher stops as "Mama Bavaria". Focus Online , February 28, 2018, accessed February 28, 2018.

- ↑ a b c d Frank Otten: Ludwig Michael Schwanthaler 1802–1848 . Studies on the Art of the Nineteenth Century, Volume 12. Prestel-Verlag Munich 1970, ISBN 3791303058 . Chapter The Bavaria in Munich , pages 60-64

- ↑ Ursula Vedder : The Bavaria in front of the Hall of Fame and other "brothers" and "sisters" of the Colossus of Rhodes , there four subpages to Bavaria

- ↑ Christian Schaaf: The Hall of Fame and the Bavaria in Munich as a particular state national monument. ( Memento from September 27, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF download) Term paper, presented at the historical seminar of the Ludwig Maximilians University in Munich, Department of Modern and Contemporary History, in the advanced seminar with Johannes Paulmann: The nation on display. Self-portrayals of the nation in the 19th and 20th centuries, winter semester 2000/2001

- ↑ BAYERN TOURISMUS Marketing GmbH (ed.): Market research brochure Tourism in Bavaria: Statistics & Figures 2016 (PDF), p. 14

- ↑ Denis A. Chevalley: The urban development in the southern and western urban areas on the left of the Isar . In: Denis A. Chevalley, Timm Weski: Monuments in Bavaria - State Capital Munich, Southwest , Volume I.2 / 2. Lipp, Munich 2004, ISBN 3-87490-584-5 , page LXV – LXIX

- ^ DGB region Munich: May 1st in Munich. Press report about the Nazi May celebrations in Munich in 1934

Coordinates: 48 ° 7 ′ 50.4 ″ N , 11 ° 32 ′ 45.6 ″ E