World Chess Championship: Difference between revisions

Undo. He's Russian. See Talk page |

|||

| Line 79: | Line 79: | ||

|[[Anatoly Karpov]]|| 1975–1985|| {{USSR}} ({{RUS}}) |

|[[Anatoly Karpov]]|| 1975–1985|| {{USSR}} ({{RUS}}) |

||

|- |

|- |

||

|[[Garry Kasparov]]|| 1985–1993|| {{USSR}} / {{ |

|[[Garry Kasparov]]|| 1985–1993|| {{USSR}} / {{RUS}} |

||

|} |

|} |

||

{{col-begin}} |

{{col-begin}} |

||

Revision as of 08:38, 3 February 2008

The World Chess Championship is played to determine the World Champion in the board game chess. Both men and women are eligible to contest this title.

In addition, there is a separate event for women only, for the title of "Women's World Champion", and separate competitions and titles for juniors, seniors and computers. However, these days the strongest competitors in the junior, senior, and women's categories often forego these niche title events in order to pursue top level competition, although they continue to be part of chess tradition. Computers are barred from competing for the open title.

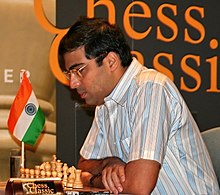

The official world championship is generally regarded to have begun in 1886, when the two leading players in the world played a match. From 1886 to 1946, the championship was conducted on an informal basis, with a challenger having to defeat the incumbent in a match to become the new world champion. From 1948 to 1993, the championship was administered by FIDE, the international chess organization. In 1993, the reigning champion (Garry Kasparov) broke away from FIDE, meaning there were two rival championships. This situation remained until 2006, when the title was unified at the World Chess Championship 2006. The most recent championship was the World Chess Championship 2007, won by Viswanathan Anand.

Reigns of the champions

See also image gallery and List of chess world championship matches.

Leading chess masters before 1886

| Name | Years | Country |

|---|---|---|

| Luis Ramirez Lucena | ~1490 | |

| Pedro Damião | ~1520 | |

| Ruy López de Segura | ~1560 | |

| Paolo Boi and Leonardo da Cutri |

~1575 | |

| Alessandro Salvio | ~1600 | |

| Gioachino Greco | ~1620 | |

| Legall de Kermeur | ~1730–1747 | |

| Francois-André Philidor | ~1747–1795 | |

| Alexandre Deschapelles | ~1800–1820 | |

| Louis de la Bourdonnais | ~1820–1840 | |

| Howard Staunton | 1843–1851 | |

| Adolf Anderssen | 1851–1858 | |

| Paul Morphy | 1858–1862 | |

| Adolf Anderssen | 1862–1866 | |

| Wilhelm Steinitz | 1866–1886 |

Undisputed world champions 1886–1993

| Name | Years | Country |

|---|---|---|

| Wilhelm Steinitz | 1886–1894 | |

| Emanuel Lasker | 1894–1921 | |

| José Raúl Capablanca | 1921–1927 | |

| Alexander Alekhine | 1927–1935 | |

| Max Euwe | 1935–1937 | |

| Alexander Alekhine | 1937–1946 | |

| Mikhail Botvinnik | 1948–1957 | |

| Vasily Smyslov | 1957–1958 | |

| Mikhail Botvinnik | 1958–1960 | |

| Mikhail Tal | 1960–1961 | |

| Mikhail Botvinnik | 1961–1963 | |

| Tigran Petrosian | 1963–1969 | |

| Boris Spassky | 1969–1972 | |

| Robert J. Fischer | 1972–1975 | |

| Anatoly Karpov | 1975–1985 | |

| Garry Kasparov | 1985–1993 |

FIDE world champions 1993–2006

|

Classical world champions 1993–2006

|

Undisputed world champions 2006–present

| Name | Years | Country |

|---|---|---|

| Vladimir Kramnik | 2006–2007 | |

| Viswanathan Anand | 2007–present |

History of the world chess championship

Unofficial champions (pre-1886)

The first match proclaimed by the players as for the world championship was the match that Wilhelm Steinitz won against Johannes Zukertort in 1886. However, a line of players regarded as the strongest (or at least the most famous) in the world extends back hundreds of years beyond them, and these players are sometimes considered the world champions of their time. They include Ruy López de Segura around 1560, Paolo Boi and Leonardo da Cutri around 1575, Alessandro Salvio around 1600, and Gioachino Greco around 1620.

In the 18th and early 19th century, French players dominated, with Legall de Kermeur (1730–1747), Francois-André Philidor (1747–1795), Alexandre Deschapelles (1800–1820) and Louis de la Bourdonnais (1820–1840) all widely regarded as the strongest players of their time. La Bourdonnais played a series of six matches — and 85 games — against the Irishman Alexander McDonnell, with many of the encounters later being annotated by the American Paul Morphy.

The Englishman Howard Staunton's match victory over another Frenchman, Pierre Charles Fournier de Saint-Amant, in 1843 is considered to have established him as the world's strongest player.[1] In 1851 Staunton organised the first international tournament in London. He finished fourth, with the decisive winner, the German Adolf Anderssen establishing himself as the leading player in the world.[2]

Anderssen was a brilliant attacking player, with two of his best games known as the Immortal Game and the Evergreen Game respectively. He has been described as the first modern chess master.[3]

Anderssen was himself decisively defeated in an 1858 match against the American Paul Morphy, after which Morphy was toasted across the chess-playing world as the world chess champion. A fast player (he took only minutes to decide on his moves, compared with some others who "were notorious not for out-thinking their opponents but out-sitting them", as Steinitz once said), and possessing fearsome talent, he played matches against several leading players, crushing them all.[4] Soon after, he offered pawn and move odds to anyone who would play him. Finding no takers, Morphy abruptly retired from chess the following year, but many considered him the world champion until his death in 1884. His sudden withdrawal from chess at his peak and subsequent mental illness led to his being known as "the pride and sorrow of chess".

This left Anderssen again as possibly the world's strongest active player, a reputation he reinforced by winning the strong London tournament of 1862.

Anderssen was narrowly defeated in an 1866 match against Wilhelm Steinitz, and some commentators regard this to be the first "official" world championship match.[5] The match was not declared to be a world championship at the time, and it was only after Morphy's death in 1884 that such a match was declared, a testament to Morphy's dominance of the game (even though he had not played publicly for 25 years).[6] The use of the term "World Chess Champion" in this era is varied, but it appears that Steinitz, at least in later life, dated his reign from this 1866 match.[7]

In 1883, Johannes Zukertort won a major international tournament in London, ahead of nearly every leading player in the world, including Steinitz.[8] This tournament established Steinitz and Zukertort as the best two players in the world, and led to the inaugural World Championship match between these two.[9] This 1886 match between Steinitz and Zukertort, won by Steinitz, though not held under the aegis of any official body, is generally recognized as the first official World Chess Championship match, with Steinitz the game's first official World Champion.

Official champions before FIDE (1886-1946)

The championship was conducted on a fairly informal basis through the remainder of the nineteenth century and in the first half of the twentieth: if a player thought he was strong enough, he (or his friends) would find financial backing for a match purse and challenge the reigning world champion. If he won, he would become the new champion. There was no formal system of qualification. However, it is generally regarded that the system did on the whole produce champions who were the strongest players of their day. The players who held the title up until World War II were Steinitz, Emanuel Lasker, José Raúl Capablanca, Alexander Alekhine, and Max Euwe, each of them defeating the previous incumbent in a match.

Lasker was the first champion after Steinitz; although he didn't defend his title in 1897-1906 or 1911-1920, he did string together an impressive run of tournament victories and dominated his opponents. His success was largely due to the fact that he was an excellent practical player. In difficult or objectively lost positions he would complicate matters and use his extraordinary tactical abilities to save the game. He held the title from 1894 to 1921, the longest reign (27 years) of any champion. In that period he defended the title successfully in one-sided matches against Steinitz, Frank Marshall, Siegbert Tarrasch and Dawid Janowski, and was only seriously threatened in a tied 1910 match against Carl Schlechter.

The tournaments St. Petersburg 1909 and St. Petersburg 1914 were pivotal events of this period. Lasker won both events (sharing first with Akiba Rubinstein in 1909), followed by Capablanca and Alekhine in 1914. Tsar Nicholas II of Russia awarded the five finalists of St. Petersburg 1914 with the title Grand Master of Chess: Emanuel Lasker, José Raúl Capablanca, Alexander Alekhine, Siegbert Tarrasch, and Frank Marshall.

In 1921, Lasker lost the title to a sensational young Cuban— Capablanca. Capablanca was the last and greatest of the "natural" players: he prepared little for his games, but won them brilliantly. He possessed an astonishing insight into positions simply by glancing at them. Renowned for his ability to gradually convert the tiniest advantages into victory as well as his famous endgame skill, Capablanca was one of the most feared players in history. From a loss to Oscar Chajes in 1916 to a loss to Richard Réti in 1924, he went undefeated.

However, in 1927, he was shockingly upset by a new challenger, Alekhine. Before the match, almost nobody gave Alekhine a chance against the dominant Cuban, but Alekhine overcame Capablanca's natural skill with his unmatched drive and extensive preparation (especially deep opening analysis, which became a hallmark of all future grandmasters). The aggressive Alekhine was helped by his fearsome tactical skill, which complicated the game. He also managed to stave off a rematch against Capablanca indefinitely. In 1935, he lost the title to the logical Dutch mathematician Max Euwe, the last amateur/world champion. Alekhine later liked to blame his loss on alcohol. In 1937, at which point the two players had split their previous 56 games evenly, Alekhine did get a rematch and won the title back from Euwe. He then held it until his death in 1946.

FIDE-controlled title (1948-1993)

Soviet dominance (1948 - 1972)

Alekhine's death threw the chess world into chaos. The previous informal system could not deal with this unlikely eventuality. Though Euwe could claim a moral right to the title, he graciously allowed FIDE to step in. Though FIDE had existed since 1924, it lacked power because the strongest chess-playing nation, the Soviet Union, refused to participate. However, upon Alekhine's death, the Soviet Union joined FIDE in order to be a part of the process to select the next champion. FIDE organised a match tournament in 1948 between five of the world's strongest players: Mikhail Botvinnik, Vasily Smyslov, Paul Keres, Samuel Reshevsky, and Max Euwe himself (Reuben Fine was also invited, but declined his invitation). Botvinnik won the tournament by a large margin (as well as winning all the sub-matches against all his opponents), and thus the championship, and FIDE continued to organise the championship thereafter.

In place of the previous informal system, a new system of qualifying tournaments and matches was arranged. The world's strongest players were seeded into "Interzonal tournaments", where they were joined by players who had qualified from "Zonal tournaments". The leading finishers in these Interzonals would go on the "Candidates" stage, which was initially a tournament, later a series of knock-out matches. The winner of the Candidates Tournament would then play a match against the reigning champion (who did not have to qualify through this process) for the championship. If a champion was defeated, he had a right to join in a three way match three years later with his successor and the next challenger (in 1957, this was changed to allow a defeated champion to play a rematch one year after his loss. This system worked on a three-year cycle.

The winner of the 1948 tournament, Mikhail Botvinnik, would end up being a constant presence in championship matches for over ten years. His marked longevity at the top is generally explained by the fact that he was a tireless worker. It is said he perfected the game as a science, not a sport, through his emphasis on technique over tactics. This longevity is even more impressive considering he had hit his peak during World War II, during which international chess was suspended, and he was the first champion who was forced to play all his challengers. Perhaps most remarkably, he was not a professional chess player, but a decorated engineer by trade.

Botvinnik first successfully defended his title twice over his first six years, holding off both David Bronstein in 1951 and Vasily Smyslov in 1954. Both the matches were drawn 12-12 but Botvinnik retained the title by virtue of being defending champion. Smyslov, however, won the title in 1957 by a score of 12.5 – 9.5, only to lose it once more to Botvinnik in 1958 by a score of 12.5 – 10.5. At the time, Smyslov had the dubious pleasure of being the shortest-reigning world champion, but this 'honour' soon switched hands, to the 'Magician from Riga', Mikhail Tal.

Tal's daring, sacrificial style had brought him success in 1960, overcoming Botvinnik by a score of 12.5 – 8.5. But once more, Botvinnik was not content, and won back his title the following year in a rematch, by the score of 13 – 8, after Tal fell ill. Botvinnik has said: "If Tal would learn to program himself properly, he would have been impossible to play." Unfortunately, he did not, and many believe that Tal was never able to live up to his potential. He remains to this day the shortest-lived champion.

Botvinnik would play just one more world championship match, against the Armenian Tigran Petrosian, losing it 12.5 – 9.5. There was no rematch, because FIDE abolished the rematch rule. Botvinnik retired from championship chess (and retired from active play altogether in 1970) and occupied himself with computer chess and the creation of his famous chess school. Petrosian successfully defended his title in 1966 against Boris Spassky, winning by the narrowest of margins (12.5 – 11.5) in Moscow. Three years later, however, (once more in Moscow) he lost 12.5 – 10.5 to the same challenger.

Fischer (1972 - 1975)

The next championship, held in Reykjavík (Iceland) in 1972, saw the first non-Soviet finalist since before World War II (the first under FIDE), the young American, Bobby Fischer. Having defeated his Candidates opponents Mark Taimanov, Bent Larsen, and Tigran Petrosian (the first two by the previously unheard-of scores of 6–0), Fischer easily qualified to challenge Spassky. The so-called Match of the Century, possibly the most famous in chess history, had a shaky start: having lost the first game, Fischer defaulted the second after he failed to turn up, complaining about playing conditions. There was concern he would default the whole match rather than play, but he duly turned up for the third game and won it brilliantly. Spassky won only one more game in the rest of the match and was eventually well beaten by Fischer by a score of 12.5 – 8.5. Fischer's dominance drew many parallels to the other famed American chess champion, Paul Morphy. Unfortunately, this similarity became all too close three years later.

A line of unbroken FIDE champions had thus been established from 1948 to 1972, with each champion gaining his title by beating the previous incumbent. This came to an end in 1975, however, when reigning champion Fischer refused to defend his title against Soviet Anatoly Karpov when Fischer's demands were not met. Fischer resigned his FIDE title in writing, but privately maintained that he was still World Champion. He went into seclusion and did not play chess in public again until 1992, when he offered Spassky a rematch, again for the World Championship. The general chess public did not take this claim to the championship seriously, since both of them were well past their prime, though the match was greatly appreciated and attracted good media coverage.

Karpov and Kasparov (1975-1993)

Karpov dominated the 1970s and early 1980s with an incredible string of tournament successes. He convincingly demonstrated that he was the strongest player in the world by defending his title twice against ex-Soviet Viktor Korchnoi, first in Baguio City in 1978 and then in Merano in 1981. His "boa constrictor" style frustrated opponents, often causing them to lash out and err. This allowed him to bring the full force of his Botvinnik-learned dry technique (both Karpov and Kasparov were students at Botvinnik's school) against them, grinding his way to victory.

He eventually lost his title to a fiery, aggressive, tactical player who was equally convincing over the board: Garry Kasparov. The two of them fought five incredibly close world championship matches, in 1984 (controversially terminated without result with Karpov leading +5 -3 =40), 1985 (in which Kasparov won the title, 13-11), 1986 (narrowly won by Kasparov, 12.5–11.5), 1987 (drawn 12–12, Kasparov retaining the title), and 1990 (again narrowly won by Kasparov, 12.5–11.5).

(Further details on the 1984 match, the longest championship match to date and also the last match scored by the number of wins, can be found in the articles on Anatoly Karpov and Garry Kasparov.)

Split title (1993 - 2006)

In 1993, Kasparov and challenger Nigel Short complained of corruption and a lack of professionalism within FIDE and split from FIDE to set up the Professional Chess Association (PCA), under whose auspices they held their match. The event was orchestrated largely by Raymond Keene. Keene brought the event to London (FIDE had planned it for Manchester), and England was whipped up into something of a chess fever: Channel Four broadcast some 81 programmes on the match, the BBC also had coverage, and Short appeared in television beer commercials. Kasparov crushed Short by five points, and interest in chess in the UK soon died down.

Affronted by the PCA split, FIDE stripped Kasparov of his title and held a championship match between Karpov (champion prior to Kasparov and defeated by Short in the Candidates semi-final) and Jan Timman (defeated by Short in the Candidates final) in the Netherlands and Jakarta, Indonesia. Karpov emerged victorious.

FIDE and the PCA each held a championship cycle in 1993-96, with many of the same challengers playing in both, and Karpov and Kasparov retaining their respective titles. In the PCA cycle, Kasparov defeated Viswanathan Anand in the PCA World Chess Championship 1995. Karpov defeated Gata Kamsky in the final of the FIDE World Chess Championship 1996. Negotiations were held for a reunification match between Kasparov and Karpov in 1996-97, but nothing came of them.[10].

Soon after the 1995 championship, the PCA folded, and Kasparov had no organisation to choose his next challenger. In 1998 he formed the World Chess Council, which organised a candidates match between Alexei Shirov and Vladimir Kramnik. Shirov won the match, but negotiations for a Kasparov-Shirov match broke down, and Shirov was subsequently omitted from negotiations, much to his disgust. Plans for a 1999 or 2000 Kasparov-Anand match also broke down, and Kasparov organised a match with Kramnik in late 2000. In a major upset, Kramnik won the Classical World Chess Championship 2000 match with two wins, thirteen draws, and no losses.

FIDE, meanwhile, scrapped the Interzonal and Candidates system, instead having a large knock-out event in which a large number of players contested short matches against each other over just a few weeks. (See FIDE World Chess Championships 1998-2004). Very fast games were used to resolve ties at the end of each round, a format which some felt did not necessarily recognize the highest quality play: Kasparov refused to participate in these events, as did Kramnik after he won Kasparov's title in 2000. In the first of these events, champion Karpov was seeded straight into the final, but subsequently the champion had to qualify like other players. Karpov defended his title in the first of these championships in 1998, but resigned his title in anger at the new rules in 1999. Alexander Khalifman took the title in 1999, Anand in 2000, Ruslan Ponomariov in 2002 and Rustam Kasimdzhanov won the event in 2004.

By 2002, not only were there two rival champions, but Kasparov's strong results - he had the top Elo rating in the world and had won a string of major tournaments after losing his title in 2000 - ensured even more confusion over who was World Champion. So in May 2002, American grandmaster Yasser Seirawan led the organisation of the so-called "Prague Agreement" to reunite the world championship. Kramnik had organised a candidates tournament (won later in 2002 by Peter Leko) to choose his challenger. So it was decided that Kasparov would play the FIDE champion (Ponomariov) for the FIDE title, and the winners of the two titles would play for a unified title.

However, the matches proved difficult to finance and organise. The Kramnik-Leko match, now renamed the Classical World Chess Championship, did not take place until late 2004 (it was drawn, so Kramnik retained his title). Meanwhile, FIDE never managed to organise a Kasparov match, either with 2002 FIDE champion Ponomariov, or 2004 FIDE champion Kasimdzhanov. Partly due to his frustration at the situation, Kasparov retired from chess in 2005, still ranked #1 in the world.

Soon after, FIDE dropped the short knockout format for World Championship and announced the FIDE World Chess Championship 2005, a double round robin tournament to be held in San Luis, Argentina between eight of the leading players in the world. However Kramnik insisted that his title be decided in a match, and declined to participate. The tournament was convincingly won by the Bulgarian Veselin Topalov, and negotiations began for a Kramnik-Topalov match to unify the title.

Reunified title (2006 onwards)

The reunification match between Topalov and Kramnik was held in late 2006. After much controversy, it was won by Kramnik. Kramnik thus became the first unified and undisputed World Chess Champion since Kasparov split from FIDE to form the PCA in 1993.

Kramnik played to defend his title at the FIDE World Chess Championship 2007 in Mexico. This was an 8 player double round robin tournament, the same format as was used for the FIDE World Chess Championship 2005. This tournament was won by Viswanathan Anand, thus making him the current World Chess Champion.

The World Chess Championship 2008, will be a match between the current champion Viswanathan Anand, and 2006 champion Vladimir Kramnik. The World Chess Championship 2009 will be between the 2008 champion; and the winner of a match between 2005 FIDE champion Veselin Topalov, and Chess World Cup 2007 winner Gata Kamsky.[11]

See also

- List of chess world championship matches

- Interzonal

- Candidates Tournament

- Women's World Chess Championship

- List of national chess championships

- List of strong chess tournaments

- List of mini chess tournaments

- Chess Olympiad

- European Individual Chess Championship

- European Team Championship

- World Chess Solving Championship

- Greatest chess player of all time - includes World Champions by world title reigns

- World Junior Chess Championship

- ELO rating system

References

- ^ "From Morphy to Fischer", Israel Horowitz, (Batsford, 1973) p.3

- ^ "From Morphy to Fischer", Israel Horowitz, (Batsford, 1973) p.4

- ^ "The World's Great Chess Games", Reuben Fine, (McKay, 1976) p.17

- ^ 1858-59 Paul Morphy Matches, Mark Weeks' Chess Pages

- ^ "The World's Great Chess Games", Reuben Fine, (McKay, 1976) p.30

- ^ "The Centenary Match, Kasparov-Karpov III", Raymond Keene and David Goodman, Batsford 1986, p.2

- ^ Early Uses of 'World Chess Champion', Edward G. Winter, 2007

- ^ 1883 London Tournament, Mark Weeks' Chess Pages

- ^ "The Centenary Match, Kasparov-Karpov III", Raymond Keene and David Goodman, Batsford 1986, p.9

- ^ Kasparov Interview, The Week in Chess 206, 19th October 1998

- ^ Regulations for the 2007 - 2009 World Chess Championship Cycle, sections 4 and 5, FIDE online. Undated, but reported in Chessbase on 24-Jun-2007

External links

- Mark Weeks' pages on the championships - Contains all results and games

- Graeme Cree's World Chess Championship Page - Contains the results, and also some commentary by an amateur chess historian

- Kramnik Interview: From Steinitz to Kasparov - Kramnik shares his views on the first 13 World Chess Champions.