Bobby Fischer

|

|

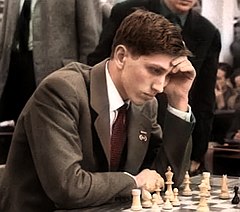

| Fischer at the Chess Olympiad in Leipzig in 1960 |

|

| Surname | Robert James Fischer |

| Association |

|

| Born | March 9, 1943 Chicago , USA |

| Died | January 17, 2008 Reykjavík |

| title |

International Master (1957) Grand Master (1958) |

| World Champion | 1972-1975 |

| Best Elo rating | 2785 (July 1972) ( Elo rating ) 2895 (October 1971) ( historical Elo rating ) |

Robert James "Bobby" Fischer (born March 9, 1943 in Chicago , Illinois , † January 17, 2008 in Reykjavík , Iceland ) was an American chess player . From 1972 to 1975 he was the 11th world chess champion . As a 16-year-old he took part in the candidate tournament, the winner of which was allowed to challenge the world champion. He won the title in 1972 in a match of the century against Boris Spassky .

After that, Fischer withdrew from tournament chess. When he did not play against the Soviet challenger Anatoly Karpov in 1975 , the World Chess Federation ( FIDE ) withdrew the world championship from Fischer. There was only one more public chess appearance in 1992 in a privately organized competition against Spasski . Fischer repeatedly expressed himself anti-American and anti-Semitic. He spent the last years of his life in Iceland , whose citizenship he had accepted. Given his undisputed achievements, Fischer is considered an outstanding figure in chess history .

life and career

Origin and youth

Fischer was born to Regina Fischer (née Wender ; 1913–1997) as a child . His mother, who was born in Zurich and grew up in the USA, studied medicine in Moscow in the 1930s. She returned to America during the Second World War . Fischer's legal father was Regina's German husband, the biophysicist Hans-Gerhardt Fischer, whom she married in Moscow in 1933 and from whom she divorced in 1945. According to speculations based on reports from the FBI , perhaps he was not Fischer's biological father , but the Hungarian engineer Paul Neményi , who had a close relationship with Regina Fischer before Fischer was born and who later regularly transferred money to her.

Together with his five years older sister Joan grew up fishing in the New York district of Brooklyn with his single mother, who worked as a nurse. He learned the rules of chess at the age of six with Joan, who, however, unlike her brother, soon lost interest in the game. His first coach was Carmine Nigro , the chairman of the Brooklyn Chess Club . In 1955, Fischer took part in the US youth championship for the first time, but was not yet able to place in the front field. From 1956 he was trained by John W. Collins , who also looked after other young talents such as William Lombardy and Robert Byrne . The psychoanalyst and former world-class player Reuben Fine , who got to know Fischer at this time, later attested that he had serious psychological problems resulting from family conflicts, which led to behavioral problems. According to Fine, the chess game offered Fischer the opportunity to avenge himself for offenses he had suffered through his success and to live out fantasies of power.

Climb to the top of chess

At the age of thirteen he became known to the chess public through the so-called " Game of the Century " on October 17, 1956 against Donald Byrne . In 1957, Fischer was named International Master by FIDE . At the age of 14, Fischer was the first US champion on January 8, 1958 - the youngest ever. Between 1958 and 1967 he won the title in all of his eight appearances, in 1964 he even managed to win all eleven games. In 1958, at the age of 15, he broke off what he considered to be useless education at the Erasmus High School in Brooklyn to devote himself entirely to chess. Robert James Fischer achieved his international breakthrough with his shared fifth place at the interzonal tournament in Portorož in August / September 1958. He thus qualified for the 1959 World Cup Candidates Tournament ; he was also awarded the title of Grand Master for his success . At the 5th Rosenwald tournament in New York in December 1958, the US championship, Fischer defeated Samuel Reshevsky for the first time , where he achieved a winning position after only eleven moves, and was again tournament winner.

At the international tournament in Zurich in 1959, Fischer defeated the Estonian Paul Keres for the first time a Soviet grandmaster. He finished the 1959 Candidates Tournament in Yugoslavia at the age of 16 in fifth place; against the eventual world champion Mikhail Tal he lost all four games. At the international tournament in Mar del Plata in April 1960, Fischer won all but two games. a. he defeated Erich Eliskases . In November 1960, during the Chess Olympiad in Leipzig, Fischer replied to a journalist's question when he thought he could become world champion: “Maybe 1963.” In the A final of this chess Olympiad, he beat Max Euwe, a former world champion, for the first time. In the summer of 1961 he played a match against Samuel Reshevsky , which was canceled after eleven games with a tie of 5½: 5½. The subsequent tournament in Bled was won by Michail Tal with 14½ points from 19 games, one point ahead of the undefeated Fischer, who won the game against the tournament winner. In his second candidate tournament , Curaçao 1962 , Fischer only finished fourth. He accused the participating Soviet players of having played mutually agreed draw games in order to save their strength for the fight against him. This criticism later led FIDE to change the mode for candidate tournaments and introduce tackles instead of round robin tournaments .

In the following years Fischer largely withdrew from tournament chess. In 1965 the US government refused Fischer a visa to take part in the Capablanca memorial tournament in Havana . So he played from New York, and the trains were teletyped . Spasski won the Piatigorsky Cup in Santa Monica in 1966 with 11½ points from 18 games, half a point ahead of Fischer and 1½ points ahead of Larsen.

Fischer's next attempt at the World Cup took place in 1967 at the interzonal tournament in Sousse . After eight rounds, he was unbeaten ahead of eventual tournament winners Bent Larsen and Samuel Reshevsky , who had only earned six points by then. He interrupted the tournament for two rounds by not appearing, then went back into the tournament process, won two more times (including against Reshevsky) and, after the disputes with the organizers were not resolved, then finally left the tournament. So this attempt at the world championship title also failed in advance. Viktor Korchnoi wrote about Fischer's insistence on special tournament conditions that were only acceptable to him in his book Mein Leben für das Schach , published in 2004 : “Chess players all over the world are indebted to him that chess has achieved this popularity, that the prices in tournaments have increased and that it has become possible to work as a chess professional in dozens of countries. "

In the following qualification cycle for the World Cup, Fischer prevailed. In 1970 he won the interzonal tournament in Palma de Mallorca and in 1971 the subsequent candidate competitions against Mark Taimanow , Bent Larsen and Tigran Petrosjan . In the quarter-finals against Taimanow and in the semi-finals against Larsen, he won each with a sensational 6-0 result. He also clearly beat ex-world champion Petrosian in the final with 6½: 2½. Fischer managed to win 20 games in a row in this cycle: first the last seven rounds in Palma de Mallorca, then six games against Taimanow, then six games against Larsen and finally the first game against Petrosjan. He won the title of world chess champion in 1972 in Reykjavík against Boris Spasski in a competition that has also become known as the " Match of the Century ". Although the duel for fisherman often sensational eccentric stood behavior several times shortly before the collapse and he even a game because of no-show by referee decision without a fight lost, he finally won after 21 games with 12½: 8½. The preliminary decision was made in the 13th game when Fischer and Black managed to win an endgame with rook and five pawns against rook, bishop and pawn after a hard fight. However, it took some persuasion to get Fischer to play at all: Henry Kissinger called him, and British millionaire Jim Slater raised the prize money.

Fischer as world chess champion

Fischer's triumph sparked a chess boom, not least in the United States. Nevertheless, he refused all offers to take part in tournaments or public exhibition fights. In 1974 rumors spread that he would not defend his title. When Anatoly Karpov was the winner of the candidate competitions, Fischer published a 179-point catalog of demands. In order to make the title match in 1975 possible, FIDE accepted almost all conditions. However, Fischer's request to interpret the planned competition in such a way that the winner should be the one who won ten games first. Since draw games should not be counted, the duration of such a competition would have been incalculable. Fischer also demanded that the reigning world champion should keep his title at the score of 9: 9. That would have meant that the challenger would have to win by two points to become world champion. When it became clear that this demand would not be met, the negotiations finally fell apart.

On April 3, 1975, Fischer was stripped of the FIDE world championship title. Karpov, against whom he had never played a game, was proclaimed his successor. After the 1972 match in Reykjavík, Fischer did not play a tournament game for almost twenty years. Nevertheless, Fischer continued to regard himself as the world chess champion in the period that followed, as no one had beaten him in a world championship match.

1992 competition against Spasski

Fischer celebrated a short comeback in 1992 when he won an unofficial match against his old rival Boris Spasski with 17.5: 12.5 in Yugoslavia during the Bosnian War with great media interest and received 3.65 million US dollars . The island of Sveti Stefan , on which the first half of the competition took place, belonged to the head of the Yugoslav private bank Jugoskandik , Jezdimir Vasiljević.

In doing so, Fischer violated the economic embargo against Yugoslavia announced by US President George HW Bush . Because of this breach of sanctions Fischer was then wanted by the US authorities with an arrest warrant ; he could face up to ten years imprisonment and a fine of up to $ 250,000 in the United States. Fischer never traveled to the USA again.

Fishermen as globetrotters

From 1975 to 2004, Fischer frequently changed his place of residence, which was mostly unknown to the public. He lived in Pasadena , San Francisco and Budapest , among others . In autumn 1990 he stayed for three months at the Hotel Pulvermühle near Waischenfeld in Franconian Switzerland .

From 2000 to 2005 Fischer lived mainly in Japan , but temporarily also in the Philippines .

Anti-Semitism and Anti-Americanism

Fischer repeatedly expressed himself anti-Semitic and anti-American . Since 1999 he has denied the Holocaust . On September 11, 2001, in a radio interview with Bombo Radyo Philippines in Tokyo, Fischer expressed praise for the terrorist attacks that day and criticized American foreign policy over the past centuries. As a result of this interview, Fischer was expelled from the US Chess Federation .

Arrest and naturalization in Iceland

In 2004, the US government revoked Fischer's passport; he was arrested on July 13, 2004 while attempting to leave Japan and detained in Ushiku near Tokyo . The United States charged Fischer with tax evasion and tried to obtain deportation from Japan in this way. His long-time partner Miyoko Watai , who was also the general secretary of the Japanese Chess Federation , initiated an international campaign aimed at his release. While Fischer was still in custody, he married Watai on August 17, 2004. In March 2005, he and his wife settled in Iceland, where he was granted political asylum and Icelandic citizenship. A spokesman for the Icelandic Ministry of Foreign Affairs announced in this context that naturalization should be seen as a "purely humanitarian gesture" and in no way implies support for Fischer's political views.

Last years in Reykjavík

When Fischer arrived in Iceland, he was in poor health. There he led a life apart from the media and continued to feel persecuted . Outside of his home, he occasionally went to restaurants and cafés and regularly went to the second-hand bookstore Bókin. The owner of an elf school , in which Icelandic folklore is collected and researched, said he spoke to Fischer about paranormal phenomena and conspiracy theories and became his confidante.

Fischer was admitted to hospital because of kidney failure , but refused a life-prolonging dialysis there. He also refused to take pain medication . Shortly before his death, Fischer asked for a photo of his mother, which he was holding in his hand when he died on January 17, 2008 in the Landspitali hospital in Reykjavík. Fischer was buried at Laugardælir Church , near the town of Selfoss . At Fischer's request, only five people attended the Catholic funeral ceremony: his wife Miyoko and the family friends of Garðar Sverrissons, who lived in the same house. Sverrisson's wife Krisín, a nurse, looked after Fischer even before his death.

heritage

Fischer left a fortune of a good two million dollars, but no will. Several parties made claims to the inheritance, including his widow Miyoko Watai, his sister Joan's two sons, the American state, and Marilyn Young, who claimed Fischer was the father of their 2002-born daughter Jinky. By order of the Icelandic Supreme Court of Hæstiréttur , an exhumation was carried out in July 2010 so that a paternity test could be carried out using a tissue sample . It was negative; Jinky is therefore not Fischer's daughter. In March 2011, the Reykjavík District Court confirmed that Watai and Fischer had been married since September 2004 and recognized her as the sole heir. His nephews were sentenced to pay Watai's legal costs of over ISK 6.6 million (around EUR 41,000 at the time ).

Books and inventions

His 1969 published book My 60 Memorable Games (dt. My 60 Memorable Games ) is still considered one of the best chess books ever. Originally the work should be called My Life In Chess ; He reserved this title, however, for a planned but never published autobiography . He worked on the analyzes for three years ; the introductory texts for the individual games were written by Larry Evans . In contrast to the game collections of many other grandmasters, he did not only record winning games. In 1995 Batsford published a new edition in algebraic notation , which was heavily criticized for unauthorized text changes. In 2004 Robert Huebner published the book Material zu Fischers Partien , in which he subjects Fischer's analyzes to an in-depth review.

As early as 1966, Fischer, together with Donn Mosenfelder and Stuart Margolies, wrote a textbook Bobby Fischer Teaches Chess ( Eng . Bobby Fischer teaches chess ). It is structured according to the principle of programmed learning and consists of 275 matte tasks that the reader should solve independently. Explanatory text and chess notation are omitted, the solutions are indicated by arrows on the chess diagrams. To date, over a million copies have been sold; this makes it the most commercially successful chess book of all time. A new edition was published in Germany in 2003.

In 1982 he self-published a booklet I was tortured in the Pasadena jailhouse! (Eng. How I Was Tortured in Pasadena Prison ), in which he made allegations of torture against US police officers who detained him for two days for mistaking him for a bank robber.

A book Searching for Bobby Fischer , published in 1988 and filmed in 1993, is not about him, but about the chess career of the young talent Joshua Waitzkin . Fischer, who had not given his approval to this title, was of the opinion that his name had only been misused for advertising purposes.

A new type of chess propagated by Fischer is Chess960 , originally "Fischer-Random-Chess", which counteracts the " heavy opening theory " of modern computer-aided chess.

In addition, he developed an electronic chess clock , which is now widely used , in which the players are given additional time to think about the basic contingent for each move made (“Fischer delay”). This avoids extreme time constraints. Fischer applied for a patent for this watch in August 1988 , but patent protection ended in November 2001 due to unpaid fees.

Play style

Fischer was considered an excellent fighter as well as a tactician . He was known for avoiding a draw and playing chess with determination and focus. Some leading players refer to him as the best player of all time.

opening

Fischer almost always used the same openings. Despite this predictability, it was difficult for the opponent to take advantage of this as he had a very extensive knowledge of these openings. In the course of his career, Fischer almost exclusively played 1. e4 with the white pieces. With the black pieces, Fischer played the Najdorf variant of the Sicilian defense against 1. e4 and the King's Indian defense as well as the Grünfeld-Indian defense against 1. d4. He seldom dared the Nimzowitsch Indian defense .

Endgame

Fischer had excellent technique in the final. The international champion Jeremy Silman counts him among the five best endgame technicians. The endgame with rook, bishop and pawn against rook, knight and pawn is also known as the "fisherman's endgame".

Awards

Fischer received the Chess Oscar from 1970 to 1972 .

Trivia

Fischer mentioned in several interviews that it is his dream to live in a house that is "built exactly like a (chess) tower". In allusion to this quote, the English post-rock band I Like Trains wrote the song A Rook House for Bobby , in which the life story of Fischer is artistically processed.

Well-known games

Movies

- Bobby Fischer Live . Feature film, USA, 2009, director: Damian Chapa , Fischer is portrayed by Damian Chapa.

- Train by train in madness (Original title: Bobby Fischer Against the World ). Documentary, USA / UK, 2011, directed by Liz Garbus .

- Pawn Sacrifice - Game of Kings (Original title: Pawn Sacrifice ). Feature film, USA / Canada, 2014, director: Edward Zwick , Bobby Fischer is portrayed by Tobey Maguire .

Publications

- Bobby Fischer's Games of Chess. Simon and Schuster, New York 1959, ISBN 0-923891-46-3 (a collection of early games, including the game of the century ).

-

Bobby Fischer Teaches Chess. Bantam, New York 1966.

- Bobby Fischer teaches chess. A programmed chess course. Joachim Beyer Verlag, Eltmann 2017, ISBN 978-3-95920-044-8 .

-

My 60 Memorable Games. Simon and Schuster, New York 1969. Batsford, London 1995, ISBN 0-7134-7812-8 (revised edition).

- My 60 memorable games. Wildhagen, Hamburg undated (approx. 1970).

literature

- Elie Agur: Bobby Fischer. His method of chess. Beyer, Hollfeld 1993, ISBN 3-89168-041-4 .

- Christiaan M. Bijl: The collected games by Robert J. Fischer . Variant, 2nd edition, Nederhorst den Berg 1986, ISBN 90-6448-515-1 .

- Hans Böhm, Kees Jongkind: Bobby Fischer. The wandering king. Batsford, London 2004, ISBN 0-7134-8935-9 .

- Frank Brady: Bobby Fischer, profile of a prodigy. McKay, New York 1973.

- Frank Brady: Endgame. Bobby Fischer's remarkable rise and fall from America's brightest prodigy to the edge of madness . Crown, New York 2011, ISBN 978-0-307-46390-6 (German: Endspiel. Genius and madness in the life of chess legend Bobby Fischer. Riva, Munich 2012, ISBN 978-3-86883-199-3 ).

- Robert E. Burger: The chess of Bobby Fischer. San Francisco 1994.

- Wolfgang Daniel: Robert James Fischer: "I really wanted to win!" Quotes, notes, stations and games from the life of a chess professional. Schneidewind, Halle 2007, ISBN 978-3-939040-16-3 .

- Petra Dautov: Bobby Fischer - as he really is. A year with the chess genius . California-Verlag, Darmstadt 1995, ISBN 3-9804281-3-3 .

- David Edmonds, John Eidinow: How Bobby Fischer won the Cold War. The most unusual game of chess ever. DVA, Munich 2005, ISBN 3-421-05654-4 ; Fischer-Taschenbuch-Verlag, Frankfurt 2007, ISBN 978-3-596-17168-2 .

- Reuben Fine : The Psychology of the Chess Player . With 2 letters from Ernest Jones . Syndikat, Frankfurt 1982, ISBN 3-8108-0204-2 (therein Bobby Fischer's fight for the world chess championship. Psychology and tactics of the title competition ).

- Johannes Fischer: chess player, nerd, genius. In: Karl . No. 2/02, p. 38.

- Robert Hübner: World Champion Fischer. ChessBase, Hamburg 2003 (CD-ROM), ISBN 3-935602-71-5 .

- ders .: Materials on Fischer's games. Rattmann, 2004, ISBN 3-88086-181-1 .

- Garry Kasparov : My great predecessors. Part IV. Fishermen . Everyman, London 2004, ISBN 1-85744-395-0 .

- Dagobert Kohlmeyer: Bobby Fischer - genius between fame and madness. Joachim Beyer Verlag, Eltmann 2013, ISBN 978-3-940417-18-3 .

- Jerzy Konikowski and Pit Schulenburg: Fischer's legacy, Joachim Beyer Verlag, Eltmann 2017, ISBN 978-3-95920-046-2 .

- Haye Kramer and Siep H. Postma: The Robert Fischer Chess Phenomenon . Variant, 2nd edition, Nederhorst den Berg 1982, ISBN 90-6448-508-9 .

- Yves Kraushaar: Bobby Fischer today. The genius between wonder and madness . Usus, Schwanden 1977.

- Manfred Mädler: The return of the phantom . Mädler, Düsseldorf 1992, ISBN 3-925691-04-9 .

- Karsten Müller : Bobby Fischer: The Career and Complete Games of the American World Chess Champion . Russell, Milford 2009, ISBN 978-1-888690-59-0 (German: Bobby Fischer. The career and all games of the American chess world champion . New In Chess, Alkmaar 2010, ISBN 978-90-5691-339-7 ).

- Helgi Ólafsson : Bobby Fischer comes home. The final years in Iceland, a saga of friendship and lost illusions . New In Chess, Alkmaar 2012, ISBN 978-90-5691-381-6 .

- Aleksander Pasternjak: Bobby Fischer. Copress-Verlag, Munich 1973; Emphasized as a chess phenomenon Bobby Fischer. Edition Olms, Zurich 1991, ISBN 3-283-00242-8 .

- Dimitry Plisetsky, Sergey Voronkov: Russians versus Fischer. Everyman Chess, London 2005, ISBN 978-1-85744-380-6 .

- Joseph G. Ponterotto: A Psychobiography of Bobby Fischer: Understanding the Genius, Mystery, and Psychological Decline of a World Chess Champion . Charles C Thomas, Springfield 2012, ISBN 978-0-398-08742-5 .

- Andrew Soltis: Bobby Fischer rediscovered. Batsford, London 2003, ISBN 0-7134-8846-8 .

Web links

- Literature by and about Bobby Fischer in the catalog of the German National Library

- Robert James Fischer, 1943-2008 , obituary by André Schulz on the ChessBase website, January 18, 2008.

- Bobby Fischer, Troubled Genius of Chess, Dies at 64 , New York Times , January 19, 2008, with a series of images (only with cookies )

- Chess legend Bobby Fischer: The irascible genius , obituary by Dennis Kayser, Spiegel Online , January 18, 2008.

- The Fischer Story. A Mystery Wrapped in an Enigma (September 2, 2015 memento in the Internet Archive ), article by William Lombardy (Fischer's second in Reykjavík 1972), Sports Illustrated , January 21, 1974.

- Chess and paranoia. Paranoia and conspiracy theories among gaming geniuses , excerpts from a lecture by Mathias Broeckers at the event series Behind the Mirrors - On the culture of play and the beauty of deep thinking , Art Hall of the Federal Republic of Germany in Bonn, November 30, 2006.

- Collection of more than 600 photos of fishermen

- Replayable chess games by Bobby Fischer on chessgames.com (English)

- Fischersetur (Fischer Museum in Selfoss, South Iceland; English / Icelandic)

- Bobby Fischer: Books about a myth , annotated bibliography of German-language books about Fischer

- Former world champion Boris Spasski in the House of History on January 21, 2007 in Bonn on Teleschach (photos, two video films and report)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Dagobert Kohlmeyer : For 65th Birthday of Robert Fischer In: de.chessbase.com. March 10, 2008, accessed October 26, 2019.

- ↑ Dagobert Kohlmeyer: Bobby Fischer on the 70th In: de.chessbase.com. March 9, 2013, accessed October 28, 2019.

- ↑ ChessBase: Fischer versus FBI - FBI versus Fischer ( memento of July 2, 2009 in the Internet Archive ), November 29, 2002; see also the photo gallery for Fischer, in: Los Angeles Times , September 21, 2009.

- ↑ Checkmate. How Bobby Fischer - world chess champion, Jew and anti-Semite - maneuvered himself out of bounds. Central Council of Jews in Germany. Volume 11 No. 8, August 26, 2011 - Aw 5771

- ↑ Reuben Fine: The Psychology of the Chess Player . In the appendix: Bobby Fischer's fight for the world chess championship. Psychology and tactics of the title competition. Syndikat, Frankfurt am Main 1982, ISBN 3-8108-0204-2 (English: The psychology of the chess player . Translated by Reinhard Kaiser, with 2 letters from Ernest Jones ).

- ↑ Chase's Calendar of Events 2008 , McGraw-Hill, New York 2008, ISBN 0-07-148903-7 , p. 31 (English).

- ↑ Johannes Fischer: 60 years ago: Bobby Fischer, 14 years old, wins the US championship. In: de.chessbase.com . January 7, 2018, accessed November 17, 2019.

- ↑ Willy Iclicki: FIDE Golden book 1924-2002 . Euroadria, Slovenia, 2002, p. 75.

- ↑ Bled Tournament. In: chessgames.com , accessed April 21, 2019.

- ^ André Schulz : Robert Fischer, 11th world chess champion. In: chessbase.com , accessed on November 26, 2018.

- ^ André Schulz: Fischer checkmates himself: Sousse 1967. In: de.chessbase.com. October 25, 2017. Retrieved November 17, 2019.

- ↑ Spasski-Fischer, 13th competition game

- ^ Leonard Barden : Obituary , in: The Guardian , January 19, 2008.

- ↑ Harald Fietz: Until all of his farmers became , rochadekuppenheim.de, accessed on May 25, 2015.

- ↑ a b Obituary for Bobby Fischer. In: Der Tagesspiegel , January 18, 2008.

- ↑ Chess in the powder mill ( Memento from February 21, 2009 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Martin Krauss: Sinn und Wahn. Jewish General of January 24, 2008.

- ↑ Fischer on the attacks on the WTC on September 11, 2001 (MP3; 1.4 MB)

- ↑ For the complicated, legally controversial procedure see u. a. here

- ↑ Dirk Jan ten Geuzendam: A lone king has wandered off / They'll do it every time . In: New In Chess , issue 2/2008. P. 21.

- ↑ René Gralla: "Free Bobby Fischer" interview with Hans-Walter Schmitt In: de.chessbase.com. August 23, 2004, accessed January 31, 2020.

- ↑ Andy Soltis on November 14, 2009 in the New York Post

- ↑ Laura Smith-Spark: Fischer 'put Iceland on the map' , BBC News , March 23, 2005.

- ^ Sara Blask, Bobby Fischer Read Here , The Smart Set, January 21, 2008.

- ↑ a b c ChessBase : Robert Fischer's secret burial , January 26, 2008 (with a photograph of the grave).

- ↑ Dirk Jan ten Geuzendam: A lone king has wandered off / They'll do it every time . In: New In Chess , issue 2/2008. Pp. 13-15.

- ↑ Dirk Jan ten Geuzendam: A lone king has wandered off / They'll do it every time . In: New In Chess, issue 2/2008. Pp. 14-15.

- ↑ Idiosyncratic genius: Chess legend Bobby Fischer is dead . In: Zeit online , January 18, 2008.

- ↑ Philipp Gessler: World Chess Champion Bobby Fischer: The long descent of a legend . In: The daily newspaper: taz . January 18, 2019, ISSN 0931-9085 ( taz.de [accessed March 15, 2019]).

- ↑ Tissue sample obtained from Fischer's grave , Chessbase.com, July 5, 2010.

- ↑ spiegel.de , accessed on September 2, 2010.

- ↑ Miyoko Watai ruled Bobby Fischer's legal marriage. Iceland Review , March 3, 2011, accessed October 16, 2017 .

- ↑ Dylan Loeb McClain: Iceland Court hands Bobby Fischer estate to japanese claimant. The New York Times , March 4, 2011, accessed October 16, 2017 .

- ↑ Edward Winter : Fischer's fury on chesshistory.com, 1999, with updates.

- ↑ Patent US4884255 : Digital chess clock. Inventor: Robert J. Fischer.

- ↑ Brady 2011, p. 328; Müller 2009, p. 23; Patrick Wolff : The Complete Idiot's Guide to Chess . 2nd Edition. Macmillan, 2001, p. 273 (first edition: 1997). William Lombardy : Understanding Chess: My System, My Games, My Life . Russell Enterprises, 2011, ISBN 978-1-936490-22-6 , pp. 220 . Harold C. Schonberg : Grandmasters of Chess . JB Lippincott, 1973, ISBN 0-397-01004-4 , pp. 271, 302 . Fred Waitzkin : Mortal Games: The Turbulent Genius of Garry Kasparov . G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1993, ISBN 0-399-13827-7 , pp. 275 (quotation from Kasparov).

- ↑ Dmitry Plisetsky, Sergey Voronkov: Russians versus Fischer. Everyman Chess, London 2005, ISBN 978-1-85744-380-6 , p. 270.

- ↑ Dmitry Plisetsky, Sergey Voronkov: Russians versus Fischer. Everyman Chess, London 2005, ISBN 978-1-85744-380-6 , p. 251.

- ↑ Dmitry Plisetsky, Sergey Voronkov: Russians versus Fischer. Everyman Chess, London 2005, ISBN 978-1-85744-380-6 , pp. 251-262.

- ↑ The Atlantic : Bobby Fischer's Pathetic Endgame , December 2002.

- ^ A Rook House for Bobby , 2005

- ↑ News about Bobby in: ChessBase , July 3, 2011.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Fischer, Bobby |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Fischer, Robert James |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | American chess player and world chess champion |

| DATE OF BIRTH | March 9, 1943 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Chicago , Illinois |

| DATE OF DEATH | January 17, 2008 |

| Place of death | Reykjavík |