Tigran Petrosian

|

|

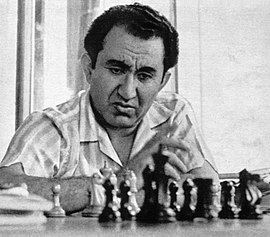

| Tigran Petrosian, 1975 |

|

| Surname | Tigran Vartanovich Petrosian |

| Association |

|

| Born | June 17, 1929 Tbilisi , USSR (now Georgia ) |

| Died | August 13, 1984 Moscow |

| title |

International Master (1952) Grand Master (1952) |

| World Champion | 1963-1969 |

| Best Elo rating | 2645 (July 1972, January 1975, January 1977) |

Tigran Petrosian Wartanowitsch ( Armenian Տիգրան Պետրոսյան , Russian Тигран Вартанович Петросян , English transcription Petrosian , 17th June 1929 in Tbilisi - 13. August 1984 in Moscow ) was a Soviet chess - grandmaster of Armenian origin and from 1963 to 1969 the ninth world chess champion . At the 1966 World Chess Championship , Petrosyan defended his title against Boris Spassky , to whom he lost the title at the 1969 World Chess Championship . Because of his defensive game and his low number of defeats in his prime, he was called the "iron Tigran".

Life and career as a player

youth

Tigran Petrosjan's father was the caretaker in the officers' home in Tbilisi. Here Tigran Petrosjan watched the soldiers play chess, at the age of 12 he learned the game himself. One of his first chess books was The Practice of My System by Aaron Nimzowitsch , which shaped his style. Soon he was discovered and looked after by the chess trainer Artschil Ebralidze . Petrosjan's mother died in the winter of 1942, and the death of his 70-year-old father in 1945 made the 15-year-old orphan. During World War II , Petrosyan contracted a severe otitis media that made him deaf in one ear.

Single player, world champion

In his first appearance outside Georgia, the USSR youth championship in Leningrad in 1945, Petrosyan shared first place with Aron Reschko and Yuri Vasilchuk. In the spring of the summer of 1946, Petrosyan moved to Yerevan , where he was trained by Genrich Gasparjan . There he received a state income that was supposed to finance his chess training, officially for a job as a chess trainer in a local club. At the age of 17 he became champion of the Armenian SSR with an 8: 6 win over Gasparjan .

Since 1949 he lived in Moscow. In 1951 he finished tied for second place in the 19th USSR Championship . Since the USSR championship was also the zone tournament , Petrosyan qualified for the interzonal tournament in Stockholm . In 1952 he became an international master ; in the same year he received the title of International Grand Master for second place in the Stockholm Interzonal Tournament. At the 1953 Candidates Tournament in Zurich , he finished 5th, in 1956 in Amsterdam and 1959 in Yugoslavia , he reached 3rd place.

In 1959 he won the USSR championship for the first time, the second time he succeeded in 1961. At the Stockholm interzonal tournament in 1962 he shared the 2nd – 3rd without defeat. Place and qualified for the candidates tournament on Curaçao in May and June. Petrosjan won the tournament without defeat and was allowed to challenge Mikhail Botvinnik to a duel for the world championship. The tournament on Curacao was overshadowed by a scandal. After the tournament, fourth-placed Bobby Fischer accused the Soviet players of having discussed their results so that in any case a Soviet player would become a challenger. He also accused them of consulting each other during the games. In fact, all games between Petrosyan, ended Paul Keres and Efim Geller with each draw , often after only a few strokes, so that starting from a non-aggression pact between the three players.

The 1963 World Chess Championship between Botvinnik and Petrosyan began on March 23 with a victory for the reigning world champion. In the fifth game Petrosyan equalized, in the seventh round he took the lead. After a series of draws, Botvinnik leveled in the 14th round. The 15th round became a key moment of the fight, in which Petrosjan outplayed his opponent and thus immediately regained the lead. After two more wins in the 18th and 19th game, Petrosjan decided the fight on May 22nd with 12.5: 9.5 (5 wins, 2 defeats, 15 draws) and became the ninth world chess champion. Botvinnik admitted after the fight that he had not been able to adjust to the unusual style of his opponent.

Petrosyan defended the title in 1966 against Boris Spassky (4 wins, 3 losses, 17 draws), but then lost it in 1969 to the same opponent (4 wins, 6 losses, 13 draws).

Later he made several attempts at the world title, but lost eliminations in 1971 against Bobby Fischer , 1974, 1977 and 1980 against Viktor Korchnoi .

In Tilburg 1981 he finished second behind Alexander Beliavsky .

National team

With the Soviet team, Petrosyan took part in the Chess Olympiads in 1958 , 1960 , 1962 , 1964 , 1966 , 1968 , 1970 , 1972 , 1974 and 1978 . 1978 the Soviet team had to be content with second place, in the other participations Petrosian won with the Soviet team. He also achieved the best individual result on the second reserve board in 1958 and 1960, on the second board in 1962, on the first board in 1966 and 1968 and on the fourth board in 1974. He won the European team championship in all eight appearances in 1957, 1961 , 1965, 1970, 1973, 1977, 1980 and 1983, and he also achieved the best individual result in 1957 on the sixth, 1961 on the fourth, 1965 on the first and 1973 on the second board. In 1970 he was nominated for the USSR against the rest of the world on the second board of the Soviet team, he was defeated by Bobby Fischer 1: 3.

Sickness and death

For the second competition between the USSR and the rest of the world in 1984, Petrosyan was originally intended for the eighth board of the Soviet team, but could not take part because of his cancer. In the same year he died of stomach cancer in Moscow .

Role as theoretician and chess author

1968 doctorate Petrosian at the philosophical faculty in Moscow with the theme Some problems of the logic of chess thinking , and received a doctorate. From 1963 to 1966 he was editor-in-chief of the magazine Schachmatnaja Moskva , from 1968 to 1977 editor-in-chief of the leading Russian chess magazine 64 .

A collection of Petrosjan's lectures on practical chess issues was published in 1988 in German translation under the title Die Schachuniversität ISBN 3-283-00234-7 .

Historical classification and souvenirs

Petrosyan is considered one of the greatest defensive players in chess history and was difficult to beat. He lost only one of 130 games in ten Chess Olympiads , the most important team competition (1972 in Skopje against the German grandmaster Robert Huebner ). His Olympic record is impressive, with 79 wins and 50 draws and only one defeat. Petrosyan got 80 percent of the possible points from his 130 games. One of his nicknames was therefore Armenia's best goalkeeper . In individual tournaments he allowed many draws - often too many for first place - but was a feared opponent in duels. Because of his hearing loss , he was insensitive to noise interference. Famous were his positional exchange sacrifice , including in his game against Samuel Reshevsky in Zurich 1953 Chess Tournament .

His highest rating was 2645; he reached it in July 1972, January 1975 and January 1977. His best historical Elo number before the introduction of the Elo numbers was 2796. He reached it in July 1962. From May 1961 to January 1964 he was number 1 in the world rankings.

The name Tigran Petrosyan was like a brand in Armenia, the grandmaster was revered as a national hero in his homeland. Petrosyan laid the first stone of the Yerevan chess house in 1967 in a park in the city center, and the chess house has been named after the player's death in 1984. Numerous streets and chess clubs are named after him. In 2005 a memorial was erected for him in Aparan . There is another monument in his honor in the Armenian capital Yerevan . His portrait has been featured on the Armenian banknote worth 2000 dram since 2018 .

Opening systems

Some variants of chess openings that he introduced or further developed are named after Petrosyan :

- In the Queen's Indian Defense 1. d2 – d4 Ng8 – f6 2. c2 – c4 e7 – e6 3. Ng1 – f3 b7 – b6 the system 4. a2 – a3 is named after him, which arises from his prophylactic style.

- King's Indian Defense : 1. d2 – d4 Ng8 – f6 2. c2 – c4 g7 – g6 3. Nb1 – c3 Bf8 – g7 4. e2 – e4 d7 – d6 5. Ng1 – f3 0–0 6. Bf1 – e2 e7– e5 7. d4 – d5 - White closes the center and will play Bc1 – g5.

- Grünfeld-Indian Defense : 1. d2 – d4 Ng8 – f6 2. c2 – c4 g7 – g6 3. Nb1 – c3 d7 – d5 4. Ng1 – f3 Bf8 – g7 5. Bc1 – g5

- French defense : 1. e2 – e4 e7 – e6 2. d2 – d4 d7 – d5 3. Nb1 – c3 Bf8 – b4 4. e4 – e5 Qd8 – d7

Game example

In the following game, Petrosyan defeated the Czechoslovakian grandmaster Luděk Pachman with the white stones in Bled in 1961 .

- Petrosyan – Pachman 1-0

- Bled, September 10, 1961

- King's Indian Attack , A07

- 1. Nf3 c5 2. g3 Nc6 3. Bg2 g6 4. 0–0 Bg7 5. d3 e6 6. e4 (The King's Indian attack is reached) Nge7 7. Re1 0–0 8. e5 d6 9. exd6 Qxd6 10. Nbd2 Qc7 11.Nb3 Nd4 12. Bf4 Qb6 13. Ne5 Nxb3 14.Nc4 (a nice speed move ) Qb5 15. axb3 a5 16. Bd6 Bf6 17. Qf3 Kg7 18. Re4 Rd8 19. Qxf6 +! Kxf6 20. Be5 + Kg5 21. Bg7 (at the end of the game a real problem move ) 1: 0

| a | b | c | d | e | f | G | H | ||

| 8th | 8th | ||||||||

| 7th | 7th | ||||||||

| 6th | 6th | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4th | 4th | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | G | H |

Private

In 1951 Petrosyan met the English teacher and translator Rona Jakowlewna Avineser, whom he married the following year. With her he had two sons, Michail and Wartan. Petrosjan's wife later had a great influence in the Soviet chess federation. Petrosyan himself said several times that he would never have become world champion without the support of his wife.

literature

- Peter Hugh Clarke: Petrosian's best games of chess 1946–63 . Bell, London 1964.

- Garry Kasparov : My great champions. The most important games of the world chess champions (Volume 5: Tigran Petrosjan, Boris Spasski). Edition Olms, Hombrechtikon / Zurich 2006, ISBN 3-283-00474-9 .

- Jerzy Konikowski , Pit Schulenburg: Tigran Petrosjan . Joachim Beyer Verlag, Eltmann 2016, ISBN 978-3-95920-031-8 (first edition 1997).

- Alexej Suetin : Tigran Petrosjan. The career of a chess genius . Verlag Bock and Kübler, Berlin 1997, ISBN 3-86155-056-3 .

Web links

- Literature by and about Tigran Petrosjan in the catalog of the German National Library

- Replayable chess games by Tigran Petrosjan on chessgames.com (English)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Andrew Soltis : Tal, Petrosian, Spassky and Korchnoi. A Chess Multibiography with 207 Games. McFarland, 2018, ISBN 978-1-4766-7146-8 , pp. 15-17.

- ↑ a b André Schulz : On the 90th birthday of Tigran Petrosian In: de.chessbase.com , June 16, 2019, accessed on September 1, 2019.

- ↑ Andrew Soltis: Tal, Petrosian, Spassky and Korchnoi. A Chess Multibiography with 207 Games. McFarland, 2018, ISBN 978-1-4766-7146-8 , p. 26.

- ↑ Jan Timman : Timman's Titans: My World Chess Champions. New In Chess, 2016, ISBN 978-90-5691-672-5 , p. 148.

- ↑ Andrew Soltis: Tal, Petrosian, Spassky and Korchnoi. A Chess Multibiography with 207 Games. McFarland, 2018, ISBN 978-1-4766-7146-8 , p. 28.

- ^ A b André Schulz: The Big Book of World Chess Championships. New in Chess, Alkmaar 2016, ISBN 978-90-5691-635-0 . Cape. 24.

- ^ Garry Kasparov: My great champions. The most important games of the world chess champions (Volume 5: Tigran Petrosjan, Boris Spasski). Edition Olms, Hombrechtikon / Zurich 2006, ISBN 3-283-00474-9 , p. 10.

- ^ Garry Kasparov: My great champions. The most important games of the world chess champions (Volume 5: Tigran Petrosjan, Boris Spasski). Edition Olms, Hombrechtikon / Zurich 2006, ISBN 3-283-00474-9 , p. 53.

- ↑ Bobby Fischer : Chess in chess. In: Der Spiegel . 41/1962. Retrieved September 10, 2019.

- ^ Johannes Fischer: The Candidates' tournaments 1959 and 1962: Stories and games. In: de.chessbase.com , March 7, 2018, accessed September 10, 2019.

- ↑ March 23, 1963. In: de.chessbase.com , March 27, 2013, accessed on September 10, 2019.

- ^ Garry Kasparov: My great champions. The most important games of the world chess champions (Volume 5: Tigran Petrosjan, Boris Spasski). Edition Olms, Hombrechtikon / Zurich 2006, ISBN 3-283-00474-9 , pp. 53-61.

- ↑ 50 years ago: Petrosyan becomes world champion. In: de.chessbase.com , April 19, 2013, accessed September 10, 2019.

- ^ Jan C. Roosendaal: Beljawski winner in Tilburg! Schach-Echo 1981, issue 21, title page (with cross table).

- ↑ Tigran Petrosjan's results at the Chess Olympiads on olimpbase.org (English)

- ↑ Tigran Petrosjan's results at the European Team Championships on olimpbase.org (English)

- ↑ report at olimpbase.org (English)

- ↑ Tigran Petrosyan: Armenia on the board: Where chess is the answer to everything . In: The daily newspaper: taz . October 15, 2016, ISSN 0931-9085 ( taz.de [accessed October 29, 2019]).

- ↑ André Schulz: Tigran Petrosian honored on a new bank note In: de.chessbase.com , February 7, 2019, accessed on October 29, 2019.

- ^ Petrosian System: The White Square Strategy. chessthinkingsystems2.blogspot.co.at, accessed February 8, 2016 .

- ↑ Petrosyan – Pachman 1961

- ↑ Genna Sosonko : The World Champions I Knew . New In Chess, 2014, ISBN 978-90-5691-484-4 , pp. 224 .

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Petrosian, Tigran |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Պետրոսյան, Տիգրան (Armenian); Петросян, Тигран Вартанович (Russian) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Armenian-Soviet chess grandmaster and world chess champion |

| DATE OF BIRTH | June 17, 1929 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Tbilisi , Georgian Soviet Socialist Republic , Transcaucasian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic , Soviet Union |

| DATE OF DEATH | August 13, 1984 |

| Place of death | Moscow |