Mikhail Tal

|

|

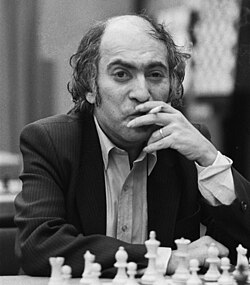

| Mikhail Tal, 1982 |

|

| Surname | Mikhail Nekhemevich Valley |

| Association |

|

| Born | November 9, 1936 Riga , Latvia |

| Died | June 27, 1992 or June 28, 1992 Moscow |

| title | Grand Master (1957) |

| World Champion | 1960-1961 |

| Best Elo rating | 2705 (January 1980) |

Mikhail Nechemjewitsch Tal ( Latvian Mihails Tāls , Russian Михаил Нехемьевич Таль ; November 9, 1936 in Riga - June 27 or June 28, 1992 in Moscow ) was a Latvian - Soviet chess player and from 1960 to 1961 the eighth world chess champion . At the world chess championship in 1960 he prevailed against Mikhail Botvinnik at the age of 23 , making him the youngest player to achieve the title of world chess champion. In the revenge fight in 1961 he lost the title again to Botvinnik. The “Magician of Riga” made a name for himself through his tactical and risky style of play. His health troubled him throughout his life. Although he had severe kidney disease , he smoked a lot and drank excessively , which was the reason for his numerous fluctuations in performance.

Despite his risky and inconsistent game, he had great tournament successes even after losing the world title: He won the Soviet championship six times , only Botvinnik came up with the same number. He remained unbeaten in 95 consecutive games between October 1973 and October 1974, which is one of the longest series in top chess to this day. In the course of his career, Tal developed his style of play towards a more universal, solid style.

life and career

Early years

Michail Tal was born on November 9, 1936 in Riga, Latvia, to a Jewish family, the son of the neurologist Nechemja Borissowitsch Tal and his wife Ida Grigoryevna Tal. Tal's parents were cousins. Tal's first wife, Sally Landau and Mark Taimanow , was not Nechemja Tal's biological father, but Robert Papirmeister, his work colleague and a close friend of the family. According to Tal's future wife Angelina, this is just an untrue rumor. Although he was born with only three fingers on his right hand ( ectrodactyly ) , possibly due to wrong medication from his mother during pregnancy, Tal played table tennis , piano and, while at school, football . After the German invasion of the Soviet Union , Tal and his family fled to Jurla in the Perm region in the west of the Ural Mountains . In November 1944, the valley returned to Riga.

At the age of seven, Tal learned to play chess, at nine he joined the chess circle in the Riga Pioneer Palace , where Jānis Krūzkops, who also trained Jānis Klovāns , became his first coach . In 1949 he first drew attention to himself with a victory over Ratmir Kholmow at a simultaneous event . In the same year he began his lifelong collaboration with Alexander Koblenz , who as a coach played a decisive role in Tal's career. He was responsible for Tal's opening preparation and psychological advice. In 1951 he took part in the Latvian State Championship for the first time, which he won in 1953 with 14.5 / 19 at the age of 17.

While in school, Tal skipped two grades. When he was fifteen, he began studying Russian language and literature at the University of Latvia , which he graduated with the state examination in 1958 . His diploma thesis dealt with the topic "The satire in the novel Twelve Chairs by Ilf and Petrow ". However, he turned to professional chess at an early age.

In 1955, Tal surprisingly won the semifinals of the 23rd USSR Championship, which took place in Leningrad in 1956 . There he finished 5th – 7th, one point behind first place. Space. Grigori Löwenfisch described Tal as the most noticeable player of the tournament and praised him as an “extraordinarily talented tactician” and a “great talent”. At the student world championship in Uppsala, Sweden in 1956, Tal appeared abroad for the first time and scored 6 points from 7 games on the third board behind Viktor Korchnoi and Lev Polugajewski for the USSR team .

Rise to the top of the world

In 1957, the 20-year-old Tal caused a sensation by winning the 24th USSR Championship in Moscow . For his victory he was named Grand Master by FIDE that same year . The following year he was also able to win the 25th edition, which was held in his hometown of Riga. The tournament was also considered a zone tournament this year , which means that Tal qualified for the interzonal tournament in Portorož , Yugoslavia . There he was victorious again and qualified as one of the top six players, including 15-year-old Bobby Fischer on his international debut, for the Candidates Tournament. In the same year he took part for the first time in the Chess Olympiad , which was held in Munich for its 13th edition in 1958 . There he got 13.5 points from 15 games on the reserve board and thus achieved the best individual result. He also met Mikhail Botvinnik there, who played on the first board for the Soviet Union. After his appearance at the Olympics, Tal was in the chess world for many as the new main competitor of the reigning world champion Botvinnik. Max Euwe , the fifth world chess champion, described Tal as an “outstanding figure in chess”. In 1959 he won the International Tournament in Zurich and finished 2nd – 3rd. Place at the Soviet championship.

In the fall of 1959, the candidates' tournament to determine the challenger for the 1960 World Chess Championship took place in the Yugoslav cities of Belgrade , Bled and Zagreb . Despite his previous performances, Tal was not one of the favorites at this tournament because he was suffering from kidney disease and had an operation a few weeks before the tournament started. Tal's competitors were Pál Benkő , Bobby Fischer, Svetozar Gligorić , Paul Keres , Friðrik Ólafsson , Tigran Petrosjan and ex-world champion Vasily Smyslow . Tal won the tournament with 20 points from 28 games 1.5 points ahead of Keres, against whom he lost the direct comparison with 1: 3. Against the eventual world champion Fischer, Tal won all four games. So he was allowed to compete in the 1960 World Cup fight against Botvinnik. In preparation for the World Cup, Tal took on the advice of his coach Koblenz at the First International Tournament in Riga - which was rather insignificant in international comparison - in order to concentrate on his defensive game, which he himself described as his " Achilles heel ", in the games there . With nine points from thirteen games, he finished fourth there.

World title and health problems

The 1960 World Chess Championship in Moscow between Mikhail Tal and Mikhail Botvinnik began on March 14th with the opening ceremony, with the first game played the next day. The competition was scheduled for 24 games, whoever reached 12.5 points first should become the new world champion. At 12:12, Botvinnik would have kept his title as defending champion. Tal had white in the first game and opened, as he had already announced at the closing ceremony of the Candidates' tournament, with 1. e4. Botvinnik chose a sharp line in the Winawer variant of the French defense , after which a complicated position arose in which Tal had the upper hand and thus took a 1-0 lead. After four draws , Tal was able to score another victory in a tactical game in the sixth game and after a mistake by Botwinnik extended his lead to 5-2 in the following game. But then Botvinnik also get two wins in a row. One of the key games of the fight was the eleventh game, in which Botvinnik Tal was defeated not on tactical, but positionally , and overlooked two easy ways to a draw. In the 17th game Botvinnik made a crucial mistake in a clearly advantageous position when time was short and cost him the game. Thus, Tal was again three wins in the lead and after several draws and a win in the 19th game after 21 games on May 7, 1960 as the eighth and up to then youngest player, the world championship title.

However, Tal lost the revenge match a year later with 8 to 13, because Botvinnik had meticulously prepared and adjusted for the opponent and had the better physique. Even then, Tal had health problems. In addition, he underestimated preparation and preferred an excessive lifestyle. Shortly before the fight, Tal fell ill and suggested postponing the match on the recommendation of his doctors. After Botvinnik requested an official investigation of Tal in Moscow, Tal decided not to postpone the fight despite his health problems. In the fall of 1961, Tal won a strong tournament in Bled, at the Soviet championship in Baku he finished 4th – 5th. Space.

In March 1962, Tal, who was increasingly struggling with kidney problems, underwent a complicated kidney operation. He had to stop the candidates tournament in 1962 on the Caribbean island of Curaçao because of severe pain after the third round and paused playing chess for a few months until he came back as a second substitute for the Soviet Union at the 15th Chess Olympiad in Varna, Bulgaria . After a shared 2nd – 3rd Place at the USSR championship in Yerevan , Tal had to pause again because of health problems and endure several operations. At the 1963 World Chess Championship between Botvinnik and Petrosyan he was a commentator . In July 1963, Tal continued his playing career when he won the Asztalos Memorial in Miskolc, Hungary , two points ahead of Dawid Bronstein . After a number of other successful tournament appearances, Tal took part in the 1964 interzonal tournament in Amsterdam , where he qualified - for the first time without a defeat - with 17 points from 23 games for the Candidates' tournament for the 1966 World Chess Championship. However , Tal was not nominated for the 1964 Chess Olympiad in Tel Aviv-Jaffa . At the 32nd USSR Championship in Kiev at the turn of the year 1964/65 he was third.

In the summer of 1965 the candidates' tournament began, which from that year on was no longer held as a round-robin tournament , but as a knockout tournament. In the quarter-finals, which took place in Bled, Tal met Lajos Portisch , against whom he was able to prevail with 5.5 to 2.5. After a week's break, Tal had an exciting match against Bent Larsen in the semifinals , which he won just under 5.5 to 4.5. In the final in Tbilisi he lost to Boris Spassky 4-7.

In the spring of 1966, Tal won the International Tournament in Sarajevo , before taking a short break at the 1966 World Chess Championship due to kidney problems and his renewed use as a commentator. At his next tournament in Kislovodsk a few months later, in which he finished sixth, his kidney continued to bother him. At the 17th Chess Olympiad in Havana , Tal came back into action and once again got the best individual result with twelve points from thirteen games on the third board. Tal missed the first four laps because he and Viktor Kortschnoi had secretly visited a night bar when someone hit Tal on the head with a bottle. According to Korchnoi, Tal, like Korchnoi himself, had problems with the chess officials of the Soviet Union, which is why he was occasionally denied trips abroad and he did not get the support that other chess grandmasters in the Soviet Union received .

In 1967 Tal won the 35th USSR Championship together with Lev Polugajewski. For the 1968 candidate competitions to determine the challenger for the 1969 World Chess Championship , Tal was qualified as one of the two finalists of the previous cycle. His quarter-final match against Svetozar Gligorić he was able to win with 5.5 to 3.5, before he was eliminated in the semifinals with 4.5 to 5.5 against Viktor Korchnoi. Despite his convincing performance two years earlier, Tal was ultimately not nominated for the 1968 Chess Olympiad in Lugano and was replaced by Vasily Smyslow shortly before the tournament began. After that, Tal showed several poor performances. After being the winner in the previous edition, Tal only landed in the middle of the field at the 36th USSR Championship and in the 37th edition with 10.5 / 22 even in the back of the field. Between these two tournaments Tal played a duel against Bent Larsen for a place in the Palma de Mallorca interzonal tournament in 1970 , where he was clearly defeated with 2.5: 5.5. The reason for this sharp drop in performance was again the worsening of his kidney problems; In this context, there was speculation about a possible morphine addiction Tal.

Because of his poor results, Tal decided to travel to Tbilisi to have his ailing kidney removed there in November 1969. Yugoslav newspapers spread the mistake that Tal died as a result of the operation.

Later successes

After his operation, Tal's shape began to rise significantly again. Just a month later, Tal was playing again when he shared 1st place at the Goglidze Memorial in Tbilisi. In 1972 he began a series of 83 unbeaten games in a row, during which he the international tournament of Sukhumi , a gold medal at the 20th Chess Olympiad in Skopje as the best single player, the 40th USSR championship in Baku and two other tournaments in Wijk aan Zee and Tallinn , won. His series ended in a team tournament of teams from the Soviet republics in Moscow against Yuri Balashov . At the interzonal tournament in Leningrad in 1973, Tal could not build on his previous performance and scored only fifty percent of the points in six defeats, at the 41st USSR Championship he was also unsuccessful with 8/17. After losing to Petrosyan on October 23, 1973 Tal began another long series of undefeated games, which lasted until a defeat on October 16, 1974 against Bulgarian grandmaster Nino Kirov at a tournament in Novi Sad. With a number of 95 games, of which he was able to win 46, Tal set a new record , which was only surpassed in 2005 by Sergey Tiviakov with 110 unbeaten games in a row.

Nevertheless, he did not succeed in the next World Cup cycle to qualify for the candidate competitions when he finished 2nd to 4th at the interzonal tournament in Biel . Shared space with Petrosjan and Portisch and ended up just behind the two in a playoff. At that time, Tal was working with world champion Anatoly Karpov , whom he also supported at the 1978 and 1981 world championships . At the 46th USSR Championship in Tbilisi, Tal won the title for the sixth time. In 1979 Tal finally managed to qualify again for the candidate competitions for the 1981 World Chess Championship when he won the interzonal tournament in Riga convincingly with 14 points from 17 games without defeat. After winning the “Tournament of Stars” in Montreal together with Karpov, Tal was the third player to achieve an Elo rating of 2700 or more . At the Candidates' Tournament in Alma-Ata in 1980 he was defeated in the quarterfinals by Lev Polugajewski with 2.5: 5.5. In January 1981 Tal began another long lossless series that lasted eighty games, albeit against weaker opponents.

Even after that, Tal continued to strive to qualify for the World Cup. In the interzonal tournament in Moscow in 1982, as in Subotica in 1987 , he missed half a point to enter the candidates' tournament . He played his last candidate tournament in Montpellier in 1985 . There he took fourth place together with Jan Timman, which entitles him to move into the semi-finals. A playoff between the two ended 3: 3, whereby Timman, who had the better ranking in the tournament, was preferred. Tal won the Berlin Summer Open in 1986 . In February 1988 he won the first official world blitz chess championship in Saint John, Canada .

Last years and death

In Manila 1990 Tal took part for the last time in an interzonal tournament, in 1991 in the last USSR championship. In both tournaments he was unsuccessful. Tal played his last tournament game, in which he was in poor health after three moves, against Vladimir Hakobjan on May 5, 1992 . After Hakobjan turned down Tal's offer for a draw, Tal won the game in an open tactical game. A month before his death he played a blitz tournament in Moscow, where he was third behind Kasparov and Yevgeny Bareev . On June 27 or 28, 1992, he died of kidney disease in a Moscow hospital.

Play style

Tal's style was very tactical , spectacular, but also risky. He often succeeded in launching an attack out of nowhere with material sacrifices against which his opponent could not find sufficient defense on the board. In many cases, Tal's combination game did not stand up to in- depth analysis and, objectively speaking, was often incorrect. In practice, however, it was almost impossible for Tal's opponents to always find the best continuation in these complicated situations over several moves, especially since time constraints often came into play. David Bronstein commented ironically on Tal's style of play: “Do you want to know how Tal wins? Very easily. He puts the pieces in the middle and then sacrifices them, no matter where. ” In addition, Tal was considered one of the world's best players in blitz chess . Because of his spectacular style, Tal was extremely popular with chess fans, especially as he was personally sociable and unconventional.

Tal's opening repertoire was considered a weakness . Tal was one of the first top players to use the Modern Benoni Defense , whose asymmetrical and risky character went well with Tal's style. Later the world champions Fischer and Kasparow also used this system.

Tal developed his style over the years and played much more solidly. Nevertheless, Tal continued to stand out for his attacking game. According to Anatoly Karpov, his combinatorial talent would initially have been sufficient, to which his opponents got used over time. This forced Tal to develop something that made his style of attack a "universal" style.

Tal was also one of those players who were said to be obsessed with chess and a "hypnotic look" . This led, among other things, to the following episode: After the American grandmaster Pál Benkő had lost his first three games against Tal in the Yugoslavia Candidates Tournament in 1959 , he competed in his fourth game - in the very last round of the tournament - with sunglasses in front of Tal Protect view. Tal, for whom a draw was enough for a sure tournament victory and thus for the world championship fight against Botwinnik, offered a draw on move 12, which Benkő refused. Tal achieved winning position shortly afterwards, but still only gave eternal check . Tal commented on the explanation: “If I want to win against Benkő, I'll win; if I want to draw against him, I'll draw. "

Game example

- Mikhail Botvinnik - Mikhail Tal 0: 1

- World Championship 1960, 6th game

- Moscow, March 26, 1960

- King's Indian Defense , E69

- 1. c4 Nf6 2. Nf3 g6 3. g3 Bg7 4. Bg2 0–0 5. d4 d6 6. Nc3 Nbd7 7. 0–0 e5 8. e4 c6 9. h3 Qb6 10. d5 cxd5 11. cxd5 Nc5 12. Ne1 Bd7 13. Nd3 Nxd3 14. Qxd3 Rfc8 15. Rb1 Nh5 16. Be3 Qb4 17. De2 Rc4 18. Rfc1 Rac8 19. Kh2 f5 20. exf5 Bxf5 21. Ra1 Nf4 !? (Diagram)

| a | b | c | d | e | f | G | H | ||

| 8th | 8th | ||||||||

| 7th | 7th | ||||||||

| 6th | 6th | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4th | 4th | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | G | H |

Kasparov describes this move as "difficult to evaluate". Objectively, according to computer analysis, the train leads to loss. In practice, however, the move creates confusing complications in which every mistake by White can lead to immediate loss, and brings Tal, who likes to play complicated positions in contrast to Botvinnik, a psychological advantage. For the “superfluous” knight, Black gets a dynamic position with numerous threats and the bishop then dominates on the long diagonal.

Kasparov even sees the move 21.… Nf4 as “decisive for Tal's victory” in the world championship fight. As a result of the fascinating procession, unrest broke out in the hall and spectators applauded. Botvinnik's second Goldberg then asked that the game be moved to a closed room, which was granted six moves later after unsuccessful attempts to calm the audience down.

Tal himself sees the move as a “purely positional figure sacrifice” and as the best move in this position. If the knight sacrifice is incorrect, it would be due to the fact that he had already made a mistake. After 21.… Nf4 all black pieces, especially the bishop on g7, who was previously out of play, would become very active.

- 22. gxf4 exf4 23. Bd2?

At this point Botvinnik would have with 23. a3! can come into a decisive advantage: after 23.… Qb3 24. Bxa7 Be5 25. f3! b6 26. a4 !! White threatens to free his bishop with a4 – a5, against which there is no adequate defense. Kasparov regards it as almost impossible to find this winning way on the board, since numerous side variants have to be taken into account. Tal does not take into account the move 26. a4 in his analysis and after 26. Qd1 gives a variant that leads to a draw through perpetual chess .

- 23.… Qxb2 !?

At this point Tal could have got into a better position with the move 23.… Be5, which he had already noted on his score sheet but ultimately did not take. After 24. f3 Qxb2 25. Nd1 Qd4 26. Rxc4 Rxc4 27. Rc1 Rxc1 28. Bxc1 Qxd5 29.Nf2 there is a position in which it is only about two results and Botwinnik has no chance of victory. After the move, White has another chance, which both Botvinnik and Tal missed.

- 24. Tab1 f3 25.Rxb2 ??

After 25. Bxf3 Bxb1 26. Rxb1 Qc2 27. Rc1 Qb2 28. Rb1 Qc2 29. Rc1 White could have forced a repetition and thus the draw. A few days after the game Salo Flohr even found a way to win for White with 27.Be4 Rxe4 28.Nxe4 Qxb1 29.Nxd6 Rf8 30. Qe6 + Kh8 31.Nf7 + Rxf7 32.Qxf7 Qf5 33.Qxf5 gxf5 34.Kg3 with White winning the endgame . Tal and Koblenz emphasize that these variations can hardly be found on the board. After the move, White is lost.

- 25.… fxe2 26. Rb3 Rd4 27. Be1 Be5 + 28. Kg1 Bf4

At this point, the main referee Gideon Ståhlberg decided to move the game from the stage to a closed room.

- 29.Nxe2 Rxc1 30.Nxd4 Rxe1 + 31. Bf1 Be4 32. Ne2 Be5 33. f4 Bf6 34.Rxb7 Bxd5 35.Rc7 Bxa2 36.Rxa7 Bc4 37.Ra8 + Kf7 38.Ra7 + Ke6 39.Ra3 d5 40.Kf2 Bh4 + 41. Kg2 Kd6 42.Ng3 Bxg3 43. Bxc4 dxc4 44. Kxg3 Kd5 45.Ra7 c3 46.Rc7 Kd4 47.Rd7 + 0: 1

Private

Tal was married three times and had two children. In 1959 he married the 19-year-old singer and dancer Sally Landau from Riga. With her he had a son who was named Gera. After the birth of his son in 1960, the marriage began to crumble, and both Tal and his wife had an affair. While the valley lived in Moscow, he learned early 1960s, the seven and a half years older actress and KGB - agent Larissa Sobolewskaja , with whom he held a long-standing relationship. After Landau divorced Tal after much back and forth, he married a Georgian noblewoman in the summer of 1970. However, this marriage did not last long, because the Georgian had only married Tal to make a former lover jealous and win back. Shortly afterwards he met his future wife Angelina, with whom he was married until his death. With her he had a daughter named Schanna, who was born in 1975.

Tal was seen as friendly, personally approachable and humorous. At the same time, he was clumsy with many everyday activities and needed outside help for the simplest things.

author

Tal was also considered an excellent commentator who did not get lost in a multitude of variants, but instead focused on the essentials. His book about his successful world championship fight with Botvinnik, as well as his autobiography The Life and Games of Mikhail Tal , in which he talks about his career in the form of an interview with himself, is considered a classic of chess literature . In the 1960s he wrote for the Latvian chess magazine Šahs , which had a circulation of 68,500 copies.

Awards

- 1960: Badge of Honor of the Soviet Union

- 1960: Honored Master of Sports

- 1981: Order of Friendship between Nations

souvenir

The Tal memorial was erected in his honor in Tal's birthplace, Latvia's capital Riga . In 2011 a street in Riga was named after him. In 2001, the Latvian Post issued a stamp to mark the 40th anniversary of Tal's world championship.

The chess museum in Chess City in the Kalmyk capital Elista is named after Michail Tal.

The Tal Memorial in Moscow has been held annually since 2006 .

The documentary Mikhail Tal was published in Latvia in 2016 about Tal's life . From a far . The opera Mikhail and Mikhail Play Chess by the Latvian composer Kristaps Pētersons processes the sixth part of Tal's 1960 World Cup fight against Mikhail Botvinnik.

Tournament and competition results

Individually

Tal won the Soviet championship six times (1957, 1958, 1967, 1972, 1974, 1978), making him the record champions together with Mikhail Botvinnik.

National team

From the late 1950s until the first half of the 1980s, Tal was regularly called up to the Soviet national team. He took part in eight Chess Olympiads ( 1958 , 1960 , 1962 , 1966 , 1972 , 1974 , 1980 and 1982 ), all of which he won with the team. He also won five individual gold medals (1958 on the first reserve board, 1962 on the second reserve board, 1966 on the third board, 1972 on the fourth board and 1974 on the first reserve board) and two silver medals (1960 on the first board and 1982 on the first reserve board).

He won the European team championship in 1957, 1961 in Oberhausen , 1970, 1973, 1977 and 1980 with the USSR team.

In both 1970 and 1984 Tal was called up for the USSR versus the rest of the world match in the Soviet selection. In 1970 he played 2-2 on the ninth board against Miguel Najdorf , in 1984 he played three games on the seventh board. Against John Nunn he managed a win and a draw, against Murray Chandler he played a draw.

societies

In the Soviet club championship Tal played for Daugava until 1976 , in 1984 he played for the Trud team, with whom he also won the European Club Cup in 1984 and reached the final of the European Club Cup in 1986. In the German federal chess league he played in the 1989/90 season for SK Zehlendorf and from 1990 to 1992 for SG Porz , with which he also took part in the 1992 European Club Cup.

literature

Works

- Tal – Botvinnik 1960. Revised 5th edition. Russell, Milford 2000, ISBN 1-888690-08-9 (Latvian original edition: Riga 1961).

- World Championship: Petrosian vs. Spassky 1966. Chess Digest Magazine, 1973.

- The Life and Games of Mikhail Tal. Cadogan Chess, London 1997, ISBN 1-85744-202-4 .

- with Alexander Koblenz :

- Study Chess with Tal. Batsford Chess, 1978, ISBN 0-7134-3606-9 .

- Chess training with ex-world champion Tal . Rau, Düsseldorf 1978, ISBN 3-7919-0178-8 .

- with Wiktor Chenkin: Tal's Winning Chess Combinations. Simon & Schuster , 1979, ISBN 0-671-24262-8 .

- with Viktor I. Schepisni and Alexander Roschal : Montreal 1979 . Pergamon Press , Oxford 1980, ISBN 0-08-024131-X .

- with EB Edmondson: Chess Scandals: The Nineteen Seventy-Eight World Championship Match. Pergamon Press, 1981, ISBN 978-0-08-024145-6 .

- with Ken Neat and Jakov Damskij: Attack with Mikhail Tal. Macmillan Publishers , 1994, ISBN 1-85744-043-9 .

Secondary literature

- József Hajtun: Valley of the Chess Magicians . Rau, Düsseldorf 1961.

- Sally Landau: Checkmate! The Love Story of Mikhail Tal and Sally Landau. Elk and Ruby Publishing House, Moscow 2019, ISBN 978-5-604-17696-2 .

- Tibor Károlyi: Mikhail Tal's Best Games . 3 volumes. Quality Chess, Glasgow 2014-2017.

- Garri Kasparow: My great champions: The most important games of the world chess champions (Volume 4: Wassili Smyslow, Michail Tal). Edition Olms , Hombrechtikon / Zurich 2005, ISBN 3-283-00473-0 .

- Valentin Kirillov: Team Tal: An Inside Story. Ruby Publishing House, Latvia 2016, ISBN 978-5-9500433-0-7 .

- Karsten Müller , Raymund Stolze : Do magic like world chess champion Michail Tal. Edition Olms, Oetwil am See 2010, ISBN 978-3-283-01007-2 .

- Andrew Soltis : Tal, Petrosian, Spassky and Korchnoi. A Chess Multibiography with 207 Games. McFarland, 2018, ISBN 978-1-4766-7146-8 .

- Peter Hugh Clarke: Mikhail Tal's best games of chess . Bell, London 1961.

- Bernard Cafferty: Tal's 100 best games, 1961–1973 . Batsford, London 1975, ISBN 0-7134-2765-5 .

- Hilary Thomas: Complete games of Mikhail Tal . 3 volumes. Batsford, London 1979-1980.

Web links

- Literature by and about Michail Tal in the catalog of the German National Library

- Johannes Fischer: An excessive genius - world champion Michail Tal. In: Karl - The cultural chess magazine. 4/2005.

- Life and Achievements Valley

- Replayable chess games by Michail Tal on chessgames.com (English)

References and comments

- ↑ Willy Iclicki: FIDE Golden book 1924-2002. Euroadria, Slovenia, 2002, p. 74.

- ↑ Dagobert Kohlmeyer : Michail Tal on his 75th birthday In: de.chessbase.com. November 9, 2011, accessed August 21, 2019.

- ↑ a b Most sources give June 28 as the date of death, but on Tal's tombstone June 27 is given as the date of death.

- ↑ This record was exceeded at the 1985 World Chess Championship by Garry Kasparov , who won the title at the age of 22.

- ^ A b Andrew Soltis : Tal, Petrosian, Spassky and Korchnoi. A Chess Multibiography with 207 Games. McFarland, 2018, ISBN 978-1-4766-7146-8 , pp. 37-38.

- ↑ Jimmy Adams: "Let me entertain you!" The Magic of Mikhail Tal. In: New In Chess . 2011, issue 8, pp. 73-82. See pp. 80–81.

- ↑ In Memory of Janis Klovans (1935-2010). from chessbase.com, May 12, 2011, accessed March 15, 2019.

- ↑ a b c Garry Kasparov: My great champions. The most important games of the world chess champions (Volume 4: Wassili Smyslow, Michail Tal). Edition Olms, Hombrechtikon / Zurich 2005, ISBN 3-283-00473-0 , p. 141.

- ^ The Life and Games of Mikhail Tal. Cadogan Chess, London 1997, ISBN 1-85744-202-4 , p. 18.

- ↑ Andrew Soltis: Tal, Petrosian, Spassky and Korchnoi. A Chess Multibiography with 207 Games. McFarland, 2018, ISBN 978-1-4766-7146-8 , p. 40.

- ↑ a b c d e The Life and Games of Mikhail Tal. Cadogan Chess, London 1997, ISBN 1-85744-202-4 , pp. 8-16.

- ↑ a b Garry Kasparov: My great champions. The most important games of the world chess champions (Volume 4: Wassili Smyslow, Michail Tal). Edition Olms, Hombrechtikon / Zurich 2005, ISBN 3-283-00473-0 , p. 142.

- ↑ a b Garry Kasparov: My great champions. The most important games of the world chess champions (Volume 4: Wassili Smyslow, Michail Tal). Edition Olms, Hombrechtikon / Zurich 2005, ISBN 3-283-00473-0 , p. 151.

- ^ Garry Kasparov: My great champions. The most important games of the world chess champions (Volume 4: Wassili Smyslow, Michail Tal). Edition Olms, Hombrechtikon / Zurich 2005, ISBN 3-283-00473-0 , p. 147.

- ^ The Life and Games of Mikhail Tal. Cadogan Chess, London 1997, ISBN 1-85744-202-4 , pp. 66 f.

- ^ The Life and Games of Mikhail Tal. Cadogan Chess, London 1997, ISBN 1-85744-202-4 , pp. 105 f.

- ^ Garry Kasparov: My great champions. The most important games of the world chess champions (Volume 4: Wassili Smyslow, Michail Tal). Edition Olms, Hombrechtikon / Zurich 2005, ISBN 3-283-00473-0 , pp. 157–158.

- ↑ Nagesh Havanur: Mikhail Tal - A Favorite Caissas In: de.chessbase.com. November 10, 2015, accessed November 17, 2019.

- ^ Garry Kasparov: My great champions. The most important games of the world chess champions (Volume 4: Wassili Smyslow, Michail Tal). Edition Olms, Hombrechtikon / Zurich 2005, ISBN 3-283-00473-0 , pp. 166–177.

- ↑ Andrew Soltis : Tal, Petrosian, Spassky and Korchnoi. A Chess Multibiography with 207 Games. McFarland, 2018, ISBN 978-1-4766-7146-8 , p. 158.

- ↑ Michail Tal: Tal – Botvinnik 1960. Match for the World Chess Championship. SCB Distributors, 2013, p. 7 ( online ).

- ^ Garry Kasparov: My great champions. The most important games of the world chess champions (Volume 4: Wassili Smyslow, Michail Tal). Edition Olms, Hombrechtikon / Zurich 2005, ISBN 3-283-00473-0 , pp. 177–197.

- ^ Garry Kasparov: My great champions. The most important games of the world chess champions (Volume 3: Michail Botwinnik). Edition Olms, Hombrechtikon / Zurich 2004, ISBN 3-283-00472-2 , p. 144.

- ↑ a b c Aleksandar Matanović : Chess is chess , Schach-Informator Verlag, Belgrade 1990, ISBN 86-7297-020-9 , p. 63.

- ^ The Life and Games of Mikhail Tal. Cadogan Chess, London 1997, ISBN 1-85744-202-4 , pp. 230-236.

- ^ Garry Kasparov: My great champions. The most important games of the world chess champions (Volume 4: Wassili Smyslow, Michail Tal). Edition Olms, Hombrechtikon / Zurich 2005, ISBN 3-283-00473-0 , pp. 198–205.

- ^ Garry Kasparov: My great champions. The most important games of the world chess champions (Volume 4: Wassili Smyslow, Michail Tal). Edition Olms, Hombrechtikon / Zurich 2005, ISBN 3-283-00473-0 , pp. 208-215.

- ^ Garry Kasparov: My great champions. The most important games of the world chess champions (Volume 5: Tigran Petrosjan, Boris Spasski). Edition Olms, Hombrechtikon / Zurich 2006, ISBN 3-283-00474-9 , pp. 244–245.

- ^ The Life and Games of Mikhail Tal. Cadogan Chess, London 1997, ISBN 1-85744-202-4 , pp. 297-305.

- ^ The Life and Games of Mikhail Tal. Cadogan Chess, London 1997, ISBN 1-85744-202-4 , pp. 331-333.

- ↑ a b Garry Kasparov: My great champions. The most important games of the world chess champions (Volume 4: Wassili Smyslow, Michail Tal). Edition Olms, Hombrechtikon / Zurich 2005, ISBN 3-283-00473-0 , p. 218.

- ^ The Life and Games of Mikhail Tal. Cadogan Chess, London 1997, ISBN 1-85744-202-4 , p. 393.

- ^ Garry Kasparov: My great champions. The most important games of the world chess champions (Volume 4: Wassili Smyslow, Michail Tal). Edition Olms, Hombrechtikon / Zurich 2005, ISBN 3-283-00473-0 , p. 219.

- ^ The Life and Games of Mikhail Tal. Cadogan Chess, London 1997, ISBN 1-85744-202-4 , p. 411.

- ↑ Karsten Müller , Raymund Stolze : The Magic Tactics of Mikhail Tal: Learn from the Legend . New In Chess, 2014 ( limited preview in Google Book Search).

- ↑ Colin McGourty: Ding Liren follows in Tal's footsteps on chess24.com, November 8, 2018, accessed on March 24, 2019.

- ^ A b Macauley Peterson: Thing defeated! Tiviakov celebrates! at en.chessbase.com, November 11, 2018, accessed on March 17, 2019.

- ^ Garry Kasparov: My great champions. The most important games of the world chess champions (Volume 4: Wassili Smyslow, Michail Tal). Edition Olms, Hombrechtikon / Zurich 2005, ISBN 3-283-00473-0 , p. 223.

- ↑ FIDE Rating List: January 1980 at olimpbase.org, accessed on March 24, 2019.

- ^ Garry Kasparov: My great champions. The most important games of the world chess champions (Volume 4: Wassili Smyslow, Michail Tal). Edition Olms, Hombrechtikon / Zurich 2005, ISBN 3-283-00473-0 , pp. 231, 234.

- ^ Garry Kasparov: My great champions. The most important games of the world chess champions (Volume 4: Wassili Smyslow, Michail Tal). Edition Olms, Hombrechtikon / Zurich 2005, ISBN 3-283-00473-0 , p. 237.

- ^ Garry Kasparov: My great champions. The most important games of the world chess champions (Volume 4: Wassili Smyslow, Michail Tal). Edition Olms, Hombrechtikon / Zurich 2005, ISBN 3-283-00473-0 , pp. 239-240.

- ↑ Robert D. McFadden : Mikhail Tal, a Chess Grandmaster Known for His Daring, Dies at 55 , The New York Times , June 29, 1992, accessed March 24, 2019.

- ↑ Daniel Naroditsky : Tal's Sacrifices Explained on chess.com, June 6, 2014, accessed on March 24, 2019.

- ^ Evgeni Sweschnikow , Wladimir Sweschnikow : A Chess Opening Repertoire for Blitz & Rapid: Sharp, Surprising and Forcing Lines for Black and White . New In Chess, 2016, p. 8.

- ↑ Albert Silver: Schach mit Michail Tal on de.chessbase.com, June 12, 2014, accessed on May 13, 2019.

- ↑ Bryan Smith : Mikhail Tal And The Modern Benoni on chess.com, September 24, 2015, accessed May 18, 2019.

- ^ Garry Kasparov: My great champions. The most important games of the world chess champions (Volume 4: Wassili Smyslow, Michail Tal). Edition Olms, Hombrechtikon / Zurich 2005, ISBN 3-283-00473-0 , p. 241.

- ↑ Gregory Serper: I offer a draw ... or I resign! chess.com, September 2, 2013, accessed May 8, 2020 .

- ↑ a b Michail Tal: Tal – Botvinnik 1960. SCB Distributors, 2013.

- ↑ Commentary, if no other source is given, in an abridged version according to Kasparow, pp. 181–187.

- ↑ Genna Sosonko : The World Champions I Knew . New In Chess, 2014, ISBN 978-90-5691-484-4 , pp. 139 .

- ↑ a b “Even Now, He Will Not Leave Me…” In: Chess Week . No. 1144 , December 26, 2003 ( online on GMSquare.com [accessed May 30, 2019] Translation of a Russian interview with Sally Landau from the same year into English).

- ↑ Sally Landau: Checkmate! The Love Story of Mikhail Tal and Sally Landau. Elk and Ruby Publishing House, Moscow 2019, ISBN 978-5-604-17696-2 , pp. 129-135.

- ↑ Genna Sosonko: The World Champions I Knew . New In Chess, 2014, ISBN 978-90-5691-484-4 , pp. 176 .

- ↑ a b Interview with Larissa Sobolewskaja on fakty.ua, November 9, 2011, accessed on March 1, 2019 (Russian).

- ↑ Красавица-актриса, агент КГБ, Лариса Кронберг умерла в одиночестве и забвении. from ufa.bezformata.com, April 29, 2017, accessed March 1, 2019 (Russian).

- ↑ Fedor Rassakow: Skandaly sowetskoi epochi . Litres, 2017, ISBN 978-5-699-27199-3 ( online at history.wikireading.ru).

- ↑ Sally Landau: Checkmate! The Love Story of Mikhail Tal and Sally Landau. Elk and Ruby Publishing House, Moscow 2019, ISBN 978-5-604-17696-2 , pp. 159-161.

- ↑ Interview with Angelina Tal (Russian) ( Memento from November 23, 2009 in the Internet Archive ).

- ↑ Dagobert Kohlmeyer: Tal, Messiah des Schach on de.chessbase.com, November 9, 2016, accessed on March 24, 2019.

- ↑ Johannes Fischer: An Excessive Genius - World Champion Michail Tal , Karl column , accessed on March 24, 2019.

- ↑ Aldis Purs, Andrejs Plakans: Historical Dictionary of Latvia. Rowman & Littlefield , 2017, p. 321.

- ↑ Genna Sosonko: Russian Silhouettes . New In Chess, 2014, p. 160.

- ↑ Anatoli Karpow et al.: Chess - encyclopedic dictionary . Sowjetskaja enzyklopedija, Moscow 1990, ISBN 5-85270-005-3 , pp. 393-394 (Russian).

- ↑ В Риге появится улица имени Михаила Таля on rus.delfi.lv, August 24, 2011, accessed on May 12, 2019 (Russian).

- ↑ В Элисте пышно отметят десятилетие "Сити Чесс" on rosbalt.ru, September 26, 2008, accessed on May 12, 2019 (Russian).

- ↑ Mikhail Tal. From a Far on nkc.gov.lv, accessed on May 13, 2019.

- ^ André Schulz : Michail and Michail play chess. In: de.chessbase.com. March 25, 2014, accessed November 23, 2019.

- ↑ Kristaps Pētersons - Mikhail and Mikhail Play Chess on opera.lv, accessed on May 13, 2019.

- ↑ Michail Tal's results at the Chess Olympiads on olimpbase.org (English).

- ↑ Michail Tal's results at European team championships on olimpbase.org (English).

- ↑ Michail Tal's results at Soviet club championships on olimpbase.org (English).

- ↑ a b Michail Tal's results at European Club Cups on olimpbase.org (English).

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Tal, Mikhail |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Tal, Mikhail Nekhemyevich (full name); Tāls, Mihails (Latvian); Таль, Михаил Нехемьевич (Russian) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Latvian-Soviet chess player and world chess champion |

| DATE OF BIRTH | November 9, 1936 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Riga |

| DATE OF DEATH | June 27, 1992 or June 28, 1992 |

| Place of death | Moscow |