History of the Jews in Russia

The story of the Jews in Russia describes Jewish life in the Kievan Rus , the Tsarist Empire , the Soviet Union and today's Russia .

History until 1772

Antiquity

Traditions and legends connect the arrival of Jews in Armenia and Georgia with the ten lost tribes (around 722 v. Chr.) Or with the Babylonian exile (586 v. Chr.). Reliable information about Jewish settlement in this region comes from the Hellenistic period (see article Georgian Jews ). Ruins, records and grave inscriptions attest to the presence of important Jewish communities in the Greek colonies on the Black Sea, such as Chersones near Sevastopol and Pantikapaion on the site of today's Kerch (see article Krimchaks and Karaites ), but initially not in the actual regions of today's Russia. As a result of religious persecution in the Byzantine Empire fled, many Jews in these communities. At the time of the Roman-Persian Wars in the 7th century, numerous Jews emigrated to the Caucasus and maintained contact with the centers of Jewish learning in Babylonia and the Persian Empire (see article Bergjuden ). Since the early Middle Ages , Jewish traders traveled to the cities on the Silk Road and reached India and China . They traded in slaves, textiles, furs, spices and weapons. In the Hebrew literature of the Middle Ages, this region is called Erez Kena'an (Land of Canaan ).

The kingdom of the Khazars is referred to in ancient Russian literature as the “land of the Jews”, but the adoption of Judaism by the Khazarian upper class is unlikely to have occurred before 740. The medieval Russian epic tells of campaigns by Russian heroes against Jewish warriors. The advantages of converting the Khazars to Judaism could have been in a possible alliance with existing larger Jewish populations in the region.

Kievan Rus

In Kiev , at the time of the Kievan Rus , Jews lived under princely protection, and ancient Russian sources mention the "Gate of the Jews" in Kiev. As the Kiev against Vladimir Monomakh collected, they also attacked the houses of the Jews. Excerpts from disputations between monks, Christian clergy and Jews have survived in early Russian religious literature . At that time there were also Jewish communities in Chernihiv and Volodymyr-Wolynskyj . The Kiev Jews conferred with their co-religionists in Babylonia and Western Europe on religious questions. Rabbi Moses from Kiev is mentioned from the 12th century, who corresponded with Rabbenu Tam and with the Gaon Samuel ben Ali from Baghdad .

The Mongol invasion of Russia under Batu Khan in 1237 and the subsequent Mongol rule brought great suffering to Russian Jews. As a result, a large community developed - both rabbanites (followers of the rabbinical direction) and Karaites - in Feodosiya in the Crimea and in the surrounding areas. They were initially under the Christian rule of the Genoese (1260-1475) and later under the Islamic Khanate of Crimea .

Since the early 14th century, Lithuania gained control of much of western Russia.

Grand Duchy of Moscow

In the Grand Duchy of Moscow , the core of the future Russian Empire , Jews were not tolerated. This hostile attitude towards Jews was related to the general hostility towards foreigners who were viewed as heretics and agents in the service of hostile states. When Tsar Ivan IV was able to incorporate the city of Pskov into his territory for some time after the successful defense of Pskov in 1582 , he ordered all Jews who refused to convert to Christianity to be drowned in the river.

Tsarist Empire Russia

For the next two centuries, Jewish traders from Poland and Lithuania entered Russian territory either in possession of a permit or illegally, occasionally settling in border towns. At the beginning of the 19th century there were small Jewish communities in the Smolensk area . In 1738 the Jew Baruch ben Leib was arrested and accused of converting the officer Alexander Vosnitsyn to Judaism. Both were burned at the stake in Saint Petersburg . In 1742, Empress Elisabeth Petrovna ordered the expulsion of the few Jews living in her empire. When the Senate tried to revoke her deportation order, pointing out that trade in Russia and the state would be affected, the Empress replied: "I do not want any benefit from the enemies of Christ."

At the beginning of the reign of Catherine II the question arose again whether Jews should be allowed to enter the country for trade purposes. The empress was in principle favorably disposed towards accepting Jews, but had to reverse her decision in the light of negative public opinion. In the Crimea and on the Black Sea coast , which were conquered by the Turks in the course of the 5th Russian Turkish War in 1768 , the authorities did not take any coercive measures against the Jews living there and even tacitly enabled new communities to settle there. As a result of the three partitions of Poland , however, the question of the presence of Jews on Russian soil took an unexpected turn when, from 1772, hundreds of thousands of Jews suddenly became subjects of the Russian Empire.

Russian Empire: First Phase (1772–1881)

The Jews who lived in the areas conquered by Russia ("Western Region" and " Vistula Country " according to the Russian administrative name) were a separate social group. As in Poland-Lithuania, they essentially formed the middle class between the aristocracy and the big landowners on the one hand and the masses of enslaved peasants on the other. Many Jews worked as tenants of villages, mills, forests and inns or as traders and peddlers. There were also artisans who worked for landowners and farmers. It is estimated that at the beginning of the 19th century, 30% of Russian Jews were working in the hospitality and trade, 15% as craftsmen and 21% had no permanent employment. The remaining 4% worked in the religious sector and in agriculture.

The economic situation of the Jews deteriorated more and more as their right of settlement was restricted to the Pale of Settlement in western Russia. The rapid population growth and the proletarianization that followed also contributed to impoverishment. The autonomy of the Jewish communities was first recognized by the government. The Jewish educational system, based on cheder and Talmud schools , was retained.

The communities in western Russia, which came under Russian rule at the end of the 18th century, were heavily in debt. In addition to the general economic problems, special taxes such as the meat tax (Russian "Korobka") for the consumption of kosher meat and the candle tax for ritually prescribed candles on the Sabbath and on public holidays turned out to be a heavy burden for the poor. Many Jews left the small towns and settled in villages or on the estates of nobles. There was also the conflict between Hasidim and their opponents, the Mitnagdim , into which the Russian government was drawn. After complaints and slander, the Hasidic rabbi Schneur Salman was arrested in 1798 and taken to St. Petersburg for questioning. The numerous "courts" of the Hasidim, including those of the Chabad movement and the yeshivot of the Mitnagdim, i.e. H. the followers of the Gaon of Vilna , with a focus on Voloshin , together formed a particularly distinctive form of Jewish culture.

Immediately after the conquest of the Polish territories, the Russian government began to view the question of how to deal with the Jews living there as a Jewish question and planned to solve this problem either by assimilation into Russian society or by expulsion. In the first 50 years under Russian rule, the rules for Jews that had applied under Polish rule were initially retained. A decree of 1791 confirmed the right of Jews to settle in the territories conquered by Poland and allowed their settlement in the uninhabited steppes of the Black Sea coast, which had been conquered by the Turks at the end of the 18th century, as well as in the Chernigov governorates and Poltava to the right of the Dnieper . This is how the Pale of Settlement was created, which took its final form with the conquest of Bessarabia in 1812 and the formation of Congress Poland in 1815. It stretched from the Baltic Sea to the Black Sea and comprised 25 governorates, with Jews making up a ninth of the total population. The settlement of Jews was also permitted in Courland and, during the 19th century, in the Caucasus and Russian Central Asia .

The first Jewish statute was issued in 1804. It permitted the admission of Jews to all elementary, middle and high schools in Russia and also permitted the establishment of Jewish schools as long as the language of instruction was Russian, Polish or German. In the same statute the settlement of Jews and their activity as tenants in villages as well as the serving of alcoholic beverages to farmers were forbidden. Thousands of Jewish families were thus deprived of their livelihoods. The expulsion from the villages was postponed for a few years, but was systematically carried out in the Belarusian villages in 1822 .

Nicholas I.

The reign of Nicholas I forms a dark chapter in the history of Russian Jewry. The tsar tried to solve the "Jewish question" through coercion and repression. In 1827 he led the Kantonistensystem one that the forced conscription of Jewish young people aged between 12 and 25 in the Russian army envisaged. Under 18s were sent to special military schools, which were also attended by soldiers' sons. This law was a severe blow to the Lithuanian and Ukrainian communities; it was not applied to the population of the “Polish” provinces. Since the years of military service was hated, responsible for screening those responsible were forced Presser ( Yiddish Chapper set) to the young people take up. The conscription of the Russian Jews brought them no relief in other areas. They continued to be expelled from the villages as well as from Kiev, and in 1843 new Jewish settlements within 50 versts from the Russian border were prohibited. On the other hand, the government encouraged Jewish agricultural settlements and exempted farmers from military service. In southern Russia and other areas of the Pale of Settlement, numerous Jewish settlements emerged on state and privately owned land.

In the 1840s, the government began to deal with the issue of education. Since the Jews had not made use of the possibility of education in general schools offered in the Jewish Statute in 1804, the government decided to set up special schools. These schools were to be financed by a special tax ("candle tax"), which the Jews had to pay. As a preliminary measure, the government sent Max Lilienthal , a German rabbi and director of the Jewish school in Riga, on an exploration trip through the Pale of Settlement. In 1844, a decree ordered the establishment of these schools, whose teachers were to be both Christians and Jews. When Lilienthal realized that the government's real intention was to bring Christianity to the Jewish students and to eradicate their harmful Talmudic beliefs , as noted in secret additional instructions, he fled Russia. A network of schools was established by the government, whose teachers consisted of followers of the Jewish Enlightenment and were led by the Rabbinical Seminary in Vilnius and the Rabbinical Seminary in Zhytomyr .

The next phase of Nicholas I's program was to divide the Jews into two groups: “useful” and “useless”. The “useful” included wealthy merchants, artisans and farmers. The rest of the Jewish population, small traders and the poor were considered "useless" and were threatened with forced conscription into the army, where they were supposed to receive craft or agricultural training. This project met with opposition from Russian politicians and led to interventions by Western European Jews. In 1846 Moses Montefiore traveled from England to Russia for this purpose. The order to classify Jews into these categories was issued in 1851. The application was delayed by the Crimean War , but the quotas for compulsory military recruitment tripled.

Alexander II

The reign of Alexander II was marked by significant government reforms, the most important of which was the abolition of serfdom of Russian peasants in 1861. Alexander II also pursued the goal of assimilation into Russian society towards the Jews, but overturned some of the harshest resolutions of his father (including the cantonist system) and granted certain selected groups of "useful" Jews the right to settle throughout Russia . These included wealthy merchants (1859), university graduates (1861), skilled craftsmen (1865) and medical staff including nurses and midwives. The Jewish communities outside the Pale of Settlement, especially in St. Petersburg and Moscow, expanded rapidly and began to exert a significant influence on Russian Judaism.

In 1874, a general four-year conscription was introduced in Russia. Since Jewish youth with a Russian secondary school diploma received relief, numerous Jews attended Russian schools. On the other hand, Jews could not be promoted to officers. In April 1880, based on an edict from Tsar Alexander II, five philanthropists founded the later international organization ORT as a charitable "Society for Craft and Agricultural Work" to promote vocational training for Jews in Russia. Until the October Revolution of 1917, ORT existed only in the Russian Empire.

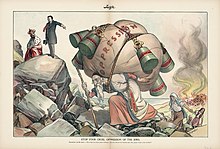

The participation of numerous Jews in the development of economic, political and cultural life - such as the musician Anton Rubinstein , the sculptor Mark Antokolski and the painter Isaak Levitan - immediately led to sharp reactions from the Russian public. Leading opponents of Judaism included prominent representatives of the Slavophile movement, such as Konstantin Aksakow and Fyodor Dostoyevsky . The Jews were accused of establishing a " state within the state " and exploiting the Russian masses; The legend of the ritual murder , which had been forbidden by law by Alexander I in 1817 , was re-established in 1878. The main argument of the hate preachers, however, was that the Jews were alien invaders into Russian life who would bring economic and cultural positions under their control and have a corrosive influence. Agitatory articles appeared in many newspapers, including the leading Novoje vremja ("New Time"). The anti-Jewish movement gained new importance , especially after the Balkan War from 1877 to 1878, which led to an increase in Slavophile nationalism throughout Russia.

Haskala in Russia

The Haskala Jewish Enlightenment movement began to gain influence in Russian Judaism in the mid-19th century . It first manifested itself in various large cities ( Odessa , Warsaw and Riga ). There were many different currents within the movement: the Poles of the Mosaic faith and nihilistic and socialist circles in Russia advocated the greatest possible assimilation, while others, including Peretz Smolenskin , were looking for a national Jewish identity. The spokesman for the Haskala in Russia was the writer Isaak Bär Levinsohn . Other leading Russian Maskilim (followers of the Haskala) were Abraham Mapu , founder of the modern Hebrew novel, and the poet Jehuda Leib Gordon (1830-1892). The Maskilim were initially opposed to the Yiddish language and wanted to replace it with Russian, but some of them, such as Mendele Moicher Sforim , later created significant secular Yiddish literature.

Russian Empire: Second Phase (1881-1917)

Alexander III

The year 1881 marked a turning point in the history of Russian Jews. The assassination attempt on Tsar Alexander II threw the whole country into confusion. Narodnaya Volya and other revolutionary groups called on the people to rebellion.

The center of the first pogrom was the Kherson Governorate . In particular from 1881 to 1882, in isolated cases until 1884, there were violent attacks. Pogroms broke out in numerous cities in southern Russia : in 1881 in Yelisavetgrad and Kiev, in 1882 in Balta , in 1883 in Yekaterinoslav , Krywyj Rih , Novomoskovsk etc. and in 1884 in Nizhny Novgorod . Jewish houses, shops and, above all, inns were looted. There were rapes and murders, the number of which can only be estimated. Aronson assumes 40 fatalities and 225 rapes in 1881 alone. According to Irwin Michael Aronson's research, the pogroms from 1881 to 1884 were, contrary to prevailing opinion, neither initiated nor wanted by the tsarist state power. Rather, the government was extremely concerned because it saw the events as part of the revolutionary plan. This does not exclude the toleration or cooperation of individual local authorities.

The fact that the Russian intelligentsia showed indifference or even sympathy for the rebels shocked many Jews, especially the Maskilim . Under the new Tsar Alexander III. Provincial commissions were appointed to investigate the causes of the pogroms. In essence, these commissions came to the conclusion that the cause of the pogroms lay in "Jewish exploitation". Based on these results, the Temporary Acts were passed in May 1882 which forbade Jews to settle outside of cities and towns (see May Laws (Russia) ). In response, there was an onslaught of Jewish students in secondary schools and colleges, whereupon a new law in 1886 limited the proportion of Jewish students in secondary schools and universities to 10% within the Pale of Settlement and 3-5% outside. This numerus clausus contributed a lot to the radicalization of Jewish youth in Russia. In 1884 the pogroms came to an end, but administrative harassment remained the order of the day. The systematic expulsion of most Jews from Moscow began in 1891. From Konstantin Pobedonoszew , the personal advisor to Tsar Alexander III, the following saying has been passed down: One third (of the Russian Jews) will die, one third will emigrate, and the last third will be completely assimilated into the Russian people.

Nicholas II

The anti-Jewish policy under Alexander III. was also continued under his successor Nicholas II . In response to the growing revolutionary movement in which Jewish youth played an increasing role, the government allowed unrestrained anti-Semitic propaganda to be spread in the press, which was subject to strict censorship regulations. During the reign of Nicholas II, numerous pogroms took place: during Passover in 1903 in Kishinev , and in 1906 in Białystok and Siedlce . The establishment of the Imperial Duma after St. Petersburg's Bloody Sunday did not improve the situation. There were 12 Jewish members of parliament in the first Duma in 1906. However, they were opposed to powerful right-wing parties such as the “ League of the Russian People ” and groups allied with it, which publicly demanded the elimination of Russian Jewry. These circles produced and published the inflammatory pamphlet " Protocols of the Elders of Zion ", through which anti-Semitic ideas are spread around the world to this day.

The pogroms and restrictive edicts as well as the administrative pressure led to mass emigration. About 2 million Jews left Russia between 1881 and 1914, many of them emigrating to the United States . Although the Jewish population of Russia did not decrease as a result of the high birth rate , their economic situation improved, especially thanks to financial support from emigrants from abroad. Various projects have been undertaken to regulate this massive emigration. The most important project came from the Jewish philanthropist Maurice de Hirsch , who in 1891 reached an agreement with the Russian government to relocate 3 million Jews to Argentina within 25 years and for this purpose founded the Jewish Colonization Association (ICA). The Argentina project did not come to fruition, but ICA was able to support agricultural settlement projects for Jews both in the emigration countries and in Russia itself. Another project for Russian Jews willing to emigrate that was also not carried out was the British Uganda Program .

The February Revolution

The nine months after the February Revolution of 1917 were a brief period of prosperity in the history of Russian Jewry. On March 16, 1917, as one of its first measures, the Provisional Government lifted all restrictions on Jews, while at the same time giving them the ability to work in administration, practice lawyers, and advance to the army. Russian Jews took an active part in the revolution and took part in the political life that flourished across the country. The Zionist movement also enjoyed great popularity among Russian Jews. In May 1917, the seventh conference of Russian Zionists was Petrograd held at the 140,000 members were represented. In many Russian cities, youth groups formed under the name Hechalutz ("The Pioneer"), who were preparing for the Aliyah to Palestine . In November 1917, news of the signing of the Balfour Declaration was received with enthusiasm.

Soviet Union

Russian civil war

After the October Revolution of 1917, a civil war developed throughout Russia that lasted until 1921. Several armies fought each other: the Ukrainian army, under the command of Symon Petlyura , joined by marauding peasant gangs; the Red Army , which also included numerous Ukrainian units; the counter-revolutionary White Army with numerous Cossacks under the command of Denikin as well as independent units such as the Machnovshchina , founded by Nestor Machno . Massacres and countless pogroms occurred particularly in Ukraine. At the beginning of 1919, while retreating from the Red Army, the Ukrainian army massacred Jews in Berdichev , Zhytomyr and Proskurov , where around 1,700 people were killed within a few hours. During the advance of the White Army from the Don region towards Moscow in the summer of 1919, a pogrom in Fastow killed 1,500 people. Simon Dubnow estimated that over a thousand pogroms flared up in Ukraine during this period, with 530 communities attacked. There were over 60,000 dead and large numbers wounded. Gunnar Heinsohn speaks of more than two thousand pogroms in Ukraine (including the Polish Ukraine), 30,000 dead and hundreds of thousands injured, of which a further 120,000 to them died inflicted injuries. The historian Orlando Figes assumes 1200 pogroms with 150,000 deaths between 1919 and 1920.

Under the Soviet regime

At the end of 1922 the borders of the Soviet Union were established. Numerous Jews who had previously lived in the Russian Empire now stayed in the states that had separated from it ( Poland , Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia and Bessarabia , which was annexed to Romania ), so that in the Soviet Union itself only 2.5 Million Jews lived. From then on, the fate of the Jews was largely determined by the Communist Party . For the Bolsheviks , integration and assimilation were the only viable path to solving the Jewish question . Lenin saw no basis for a separate Jewish nation , and as early as 1913 Stalin had declared in "Marxism and the National Question" that a nation was a stable community of people that had emerged through a historical process and was based on a common language, common territory and economic life; Since there was no such common basis among the Jews, they were only a "nation on paper" and social development therefore necessarily led to their assimilation. By fighting anti-Semitism and pogroms, the new government quickly won the sympathies of the Jewish masses, whose survival depended on their victory. Jewish youth enthusiastically joined the Red Army and took part in its construction; one of its founders was Leon Trotsky . Numerous Jews were active in the revolutionary cadres.

The Bolshevik regime , however, led to the total economic ruin of the Jewish masses, most of whom belonged to the urban petty bourgeoisie . With the abolition of private trade and property and the lifting of the status of small towns as intermediaries between farming villages and large cities, hundreds of thousands of Jewish families were deprived of their livelihoods. Around 300,000 Jews emigrated to Lithuania, Latvia, Poland and Romania in the 1920s. The end of the civil war and the introduction of the New Economic Policy (NEP) initially eased the situation somewhat, but the economic prospects of most Jews in the Soviet Union were hopelessly destroyed.

The spiritual foundations of Jewish culture were also destroyed by the Communist Party . Between 1918 and 1923, under the leadership of the war veteran Simon Dimantstein, Jewish sections (" Evsekzija ") were established within the Communist Party . Their task was to build a “Jewish proletarian culture” which, according to Stalin, should be “national in form and socialist in content”. This meant fighting the Jewish religion, Tanak studies , the Zionist movement, and the Hebrew language . In June 1921, some Hebrew authors, led by Chaim Nachman Bialik and Saul Tschernichowski, left Russia, and a few years later the Habima National Theater , which had reached a high level and had been protected for a few years by personalities like Maxim Gorky , emigrated to Palestine . On the other hand, Yiddish language and literature were officially promoted. There were three major Yiddish newspapers: Emes ( "truth", 1920-39 in Moscow), Schtern (1925-41 in Ukraine) and Oktyabr ( "October", from 1925 to 1941 in Belarus). The establishment of a Yiddish school system was also promoted. In 1932, 160,000 Jewish children in the Soviet Union attended a Yiddish-language school. However, due to the lack of higher education opportunities in Yiddish and Stalin's increasingly anti-minority policies, these schools across the country were closed in the following years.

As a Soviet alternative to Zionism, numerous Jewish agricultural settlements were established in Ukraine and Crimea in the 1920s . However, since this did not meet the needs, the government decided in 1928 to resettle Jews in the sparsely populated area around Birobidzhan in eastern Russia, where the Jewish Autonomous Oblast was proclaimed in 1934 . For the territory of the RSFSR , the 1939 census showed about 956,000 Jews.

Transit of the Jews from Poland to Japan

After the German invasion of Poland in 1939, around 10,000 Polish Jews fled to neutral Lithuania . Chiune Sugihara (1900–1986), the consul of the Japanese Empire in Lithuania, presented the plan to the Deputy People's Commissar for Foreign Relations, Vladimir Dekanosow , who was responsible for the Sovietization of Lithuania as the representative of the Moscow party leadership Japan wanted to leave the country by sending the Trans-Siberian Railway to Nakhodka ( Russian: Нахо́дка ) on the Pacific coast and then to Japan. Stalin and People's Commissar Molotov approved the plan, and on December 12, 1940, the Politburo passed a resolution that initially extended to 1991 people. According to the Soviet files, around 3,500 people traveled from Lithuania via Siberia by August 1941 to take the ship to Tsuruga in Japan and from there to Kobe or Yokohama . About 5000 of the refugees received a Japanese visa from Chiune Sugihara, with which they were supposed to travel to the Netherlands Antilles . For the rest of the Jews, however, Sugihara ignored the order to issue only transit visas and issued thousands of Jews with entry visas and not just transit visas to Japan, thereby jeopardizing his career but saving the lives of these Jews. After the German attack on the Soviet Union in 1941, there was no longer any shipping traffic between Japan and the Soviet Union, so that the flow of refugees from the Siberian mainland came to a standstill.

In World War II

The most important event for the Jews at the beginning of the Second World War was the Soviet occupation of eastern Poland from 1939 to 1941, which brought 2.17 million Jews under Soviet influence. After a professorship for Yiddish language and literature was established at the University of Vilnius , Jewish schools were soon closed and many refugees from western Poland were deported to Siberia. After the mass arrests of Jews and non-Jews in the spring of 1941, the Soviet press barely reported on the atrocities that Germany had signed a non-aggression pact with, leaving most Jews in the Soviet Union unprepared for the events to come.

In the first few weeks after the attack on the Soviet Union , German troops conquered the entire territory that had been annexed by the Soviet Union in 1939/40. Vilnius fell on June 25, 1941, Minsk on June 28, Riga on July 1, Vitebsk and Zhitomir on July 9, and Kishinev on July 16. Of the four million Jews who lived in the area later occupied by Germans in the spring of 1941, around three million were killed.

The task of the systematic murder of Jews was in the hands of four task forces formed for this purpose , which were recruited from the SS , the security service and the Gestapo . The commissioner's order of June 6, 1941 contained the mandate to cleanse the occupied territories of all so-called undesirable elements after the German troops marched into the Soviet Union: political commissioners, active communists and, above all, Jews. The German Wehrmacht supplied the Einsatzgruppen with personnel, logistics and weapons. On October 10, 1941, General Field Marshal Reichenau openly called on his soldiers to murder Jews in the "Reichenau Order":

- In the east, the soldier is not only a fighter according to the rules of the art of war, but also the bearer of an inexorable nationalist idea and the avenger for all bestialities inflicted on German and related nationalities.

- That is why the soldier must fully understand the necessity of the harsh but just atonement for Jewish subhumanity.

- It has the further purpose of nipping in the bud uprisings in the rear of the Wehrmacht, which experience shows were always instigated by Jews.

Adolf Hitler described the Reichenau order as “excellent” and ordered all army commanders on the Soviet front to follow Reichenau's example.

The local population also took part in the extermination of the Jews. The collaboration was encouraged by the Germans, for example by assigning the houses and property of the Jews to be murdered to the local population. On the other hand, there were also a few attempts to save Jews. One example of this is Metropolitan Sheptitsky , head of the Ukrainian Church , who with the help of monks hid Jews in monasteries. Similar efforts were made in Vilnius. But the prevailing conditions hampered the success of these efforts. The National Socialist methods of extermination varied from place to place. In many cases, the extermination campaigns took place immediately after the German occupation. In Kiev Jewish on 29 and 30 September 1941 33,779 men, women and children were in the valley of two days, Babi Yar killed. German and Romanian troops murdered in Odessa from November 23rd to 26th. October 1941 in revenge for the destruction of the Romanian headquarters there 26,000 Jews, many of whom were hanged or burned. In the occupied Soviet Union, new methods of murdering Jews were experimented with. One such method was the killing in closed trucks, which were supposed to be used for transportation, but whose passengers were gassed . In cases where the extermination could not be completed in the first few days after the occupation, concentration camps were temporarily set up on the outskirts as "Jewish residential areas" ( ghettos ), which were run by a Jewish council and later liquidated. See also the Maly Trostinez extermination camp .

During the Second World War, the Jewish soldiers of the Red Army were characterized by extraordinary loyalty to the Soviet Union. Of the 500,000 Jews who served in the Soviet army, about 200,000 died in combat. About 60,000 Jewish soldiers received awards during the war, 145 were honored as Hero of the Soviet Union , the highest honor in the Soviet Union. Between 10,000 and 20,000 Jews actively participated in the partisan movement , such as Abba Kovner , Jitzchak Wittenberg and the Bielski partisans . About a third of them fell in the fight against the Germans. After the German-occupied territories were regained, Jewish partisans were mobilized by the Red Army and took part in the Battle of Berlin . The Jewish Antifascist Committee was involved in Soviet war propaganda, but at the same time served as the unofficial representative of Soviet Jewry until it was dissolved in 1949.

Persecutions in the Stalin regime

Immediately after the Second World War, the situation of Jews in the Soviet Union initially seemed to improve. Rumors were spread that a "Jewish republic" for Holocaust survivors was being established on the Crimean peninsula , numerous Yiddish books were reprinted, Jewish settlement in Birobidzhan was increased, and Andrei Gromyko's speech at the UN General Assembly on April 14th. May 1947 raised hopes for support for the emerging state of Israel. But suddenly the climate changed completely. In January 1948, Solomon Michoels , chairman of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee, died under mysterious circumstances in a car accident in Minsk. On November 20, 1948, Ejnikejt , the official organ of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee, ceased publication . At the same time, all Jewish cultural institutions in the Soviet Union were liquidated. In November 1949 the anti-fascist committee was dissolved and its members arrested. Soviet newspapers waged an aggressive campaign against " rootless cosmopolitans, " by which, as a rule, were meant Jews. 25 leading members of the anti-fascist committee were charged with collaborating with Zionism and American imperialism, portraying the “Crimean Project” as an “imperialist conspiracy” to secede Crimea from the USSR; most of the accused, with the exception of Lina Stern , were executed in secret on August 12, 1952.

Anti-Semitism was also expressed in the suppressed coming to terms with the Shoah . The Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee gathered at the suggestion of Albert Einstein since the summer of 1943 documents about the murder of Jews in the area of the occupied Soviet Union to a corresponding "black book" to publish it. The project was first led by Ilya Ehrenburg , then by Wassili Grossman . The censorship authorities of the Soviet Union, however, prevented publication with the argument that the fate of the Jews was being emphasized in an inadmissible way compared to that of the ordinary Soviet citizens. The black book could never appear in the Soviet Union and only in 1980 in an Israeli publishing house (here, however, the reports from Lithuania were missing ). The first complete edition was published in German in 1994.

On January 13, 1953, the government announced the arrest of a group of prominent doctors, most of whom were Jewish. They were charged with killing members of the government using the wrong medical treatment methods in the so-called medical conspiracy and planning further killings. An anti-Semitic wave swept through the country. Many Jews lost their jobs and rumors of impending mass deportations to Siberia began to spread. The period from 1948 to Stalin's death in 1953 is known as the "Black Years". Between 1948 and 1952, all Jewish national institutions were almost completely destroyed. A religious life could only survive in a modest way. At the beginning of the 1960s, as part of the religious persecution under Khrushchev , synagogues were closed down massively. While there were 1,100 active synagogues on the much smaller territory of the Soviet Union in 1926, there were only 450 in 1956 and around 100 in 1988.

The censuses show a decline in the Jewish population: in 1970 it was only 792,000, in 1979 the number had fallen to 692,000.

Relations with Israel

From 1947 until the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Soviet-Israeli relations were marked by manifold changes, although the actual goals always remained the same. These goals were based on a combination of three factors. As early as the times of the Tsars, there was a desire that Russia should gain possibly exclusive influence in the Middle East by playing off the opposing great powers. The second, ideological factor was the leading role of the USSR in the communist world and in the "anti-imperialist" struggle against the West. Third, the Soviet government tried to solve the “Jewish question” within the USSR by eliminating the State of Israel.

From 1947 to the beginning of 1949, Soviet-Israeli relations were initially untroubled. As part of the UN , the Soviet Union supported the formation of a Jewish state in part of Palestine . The Soviet Union was very interested in a British withdrawal from Palestine and the whole of the Middle East. She hoped to achieve this goal with the establishment of a Jewish state and therefore voted with the USA on January 29, 1947 in the UN General Assembly for the partition of Palestine . The USSR supplied Israel with arms (via Czechoslovakia), provided economic aid (via Poland) and made it possible for numerous Jews from all countries in Eastern Europe to immigrate to Israel, with the exception of the Soviet Union itself. The enthusiasm of the Soviet Jews for the new state of Israel, the in September 1948 in a mass demonstration in front of the Great synagogue in Moscow to receive Golda Meir , put it, the first ambassador of Israel in the Soviet Union, however, was soon dampened. On September 21, 1948, Ilya Ehrenburg published a rejection of "distant, capitalist" Israel in Pravda : Soviet Jews do not look to the Middle East, they look to the future.

Between 1949 and 1953, at the height of the Cold War , Soviet-Israeli relations deteriorated. Anti-Semitism in the Soviet Union and Soviet-ruled countries culminated towards the end of Stalin's rule in the doctors' conspiracy and the Slansky trial in Prague , where the Israeli ambassador was declared a persona non grata . At the UN, Soviet support for Israel ceased, and Jewish emigration from Eastern European countries also came to an end. The Soviet Union refused an Israeli request for technical assistance, but economic relations did not suffer much. In February 1953, about a month before Stalin's death, the explosion of a bomb in the courtyard of the Soviet embassy in Tel Aviv served the USSR as a pretext for a brief break in diplomatic relations with Israel, which were resumed in July 1953.

The improvement in relations between the two countries did not last long. On January 22, 1954, the USSR voted against Israel for the first time in the UN Security Council . Relations with Israel reached a new low when, in the run-up to the Sinai campaign in 1956, the Soviet Union unilaterally lifted the economic agreements between the two countries. After trade turnover between the two countries exceeded $ 3 million in 1954, it fell to a little more than half that amount in the following year and decreased even more in 1956.

On the last day of the Six Day War , June 10, 1967, the Soviet Union broke off diplomatic relations with Israel. The other members of the Warsaw Pact , with the exception of Romania , followed suit. Israel's unexpectedly quick victory in the Six Day War was also a disappointing defeat for the Soviet Union, to which it responded by rearming Egypt and Syria and supporting Egypt in the war of attrition against Israel in the hope of increasing Arab dependence on the Soviet Union. The buzzwords “Soviet-Arab Alliance” and “Israel, the Nazis of the Present” shaped the Soviet Union's relations with Israel in the last decades.

The anti-Israeli and anti-Semitic policies of the Soviet Union and the ban on emigrating Jews have met with increasing international criticism since the early 1960s. At the beginning of 1962, the philosopher Bertrand Russell demanded the restoration of all civil rights for Soviet Jews in a telegram to Khrushchev , which François Mauriac and Martin Buber helped to sign. Russell's private correspondence with Khrushchev on the matter was published in the British and Soviet press and Radio Moscow in February 1963 , followed by a sharp exchange between Khrushchev and Russell. Russell continued his commitment to individual Soviet Jews and the entire Jewish community there until he had to give up his public activities in 1968 for reasons of age. In the following years more and more reports about the situation of the Jews in the Soviet Union appeared in the world press. In December 1970, in a trial in Leningrad , a group of Jews, most of them from Riga, were charged with plotting to hijack a Soviet plane to Israel. The harsh sentences - including two death sentences - were followed by international protests, whereupon the death sentences were commuted to prison sentences and the remaining sentences were also softened. A prominent representative of the "Refusniks" (people who were refused to leave the Soviet Union) was Anatoly Shcharansky, who later became Natan Sharansky , in the 1970s and 1980s .

Perestroika

After Mikhail Gorbachev took office and the perestroika he initiated , the exit regulations were relaxed.

Since the German reunification , the immigration of Russian Jews to Germany has also increased sharply. On April 12, 1990, the freely elected People's Chamber of the GDR announced in a joint declaration by all parliamentary groups that they were ready to grant persecuted Jews political asylum. As a result, around 3,000 Soviet Jews came to the GDR in the summer of 1990 . In the course of German reunification, the federal government initially ended this regulation. It was only after prolonged political pressure that the Conference of Interior Ministers decided on January 9, 1991, to extend the Law on Measures for Refugees Admitted in the Framework of Humanitarian Aid Operations (HumHAG) to include Jewish emigrants from the CIS countries, thus enabling immigration again. In the following years, these Jewish quota refugees were distributed to federal states and districts in Germany. By 2003, mainly as a result of this immigration, the number of members of Jewish communities in Germany rose from around 30,000 to 102,000.

Russia after 1991

The dissolution of the Soviet Union was marked by anti-Jewish concomitants, so that hundreds of thousands of Russian Jews emigrated from the dissolving state. Many of them emigrated to Israel, where the nationalist party Yisra'el Beitenu was founded by Russian immigrants .

Since 2000, the number of emigrants has been falling. The reason for this is the political support of President Vladimir Putin and the interreligious dialogue that has been pursued by Patriarch Kirill I since 2009 . Since then, the situation for Jews in Russia has been relatively safe, even if anti-Semitic attitudes are still voiced in Russia.

In 1999, the then Prime Minister Putin promoted the establishment of the Federation of Russian Jewish Communities with the help of the oligarchs Roman Abramowitsch and Lev Leviev, who were associated with him . The aim was to replace the previous umbrella organization for Russian Jews, the Russian Jewish Congress, which was chaired by the oligarch Vladimir Gussinsky . The Chief Rabbi of Russia, previously appointed by the Russian Jewish Congress, lost his recognition by the government in 1999, which in his place recognized Rabbi Berel Lasar of the Hasidic Chabad community as the highest spiritual representative of Judaism in Russia, who was nominated by the Federation of Russian Jewish Congregations . Gussinski was arrested and driven into exile in 2000 by Putin, who has now been elected president, after reports from his television stations criticized the government.

literature

- Alexander Solzhenitsyn : Two hundred years together. Two volumes: The Russian-Jewish History 1795–1916 and The Jews in the Soviet Union. Herbig, Munich 2002, ISBN 978-3776623567 .

- Encyclopedia Judaica . Vol. 14, pp. 433-506.

- Wassili Grossman , Ilja Ehrenburg , Arno Lustiger : The Black Book. The genocide of the Soviet Jews. Rowohlt, Reinbek 1995, ISBN 978-3-498-01655-5 .

- Ilja Altman : victim of hatred. The Holocaust in the USSR 1941–1945. With a foreword by Hans-Heinrich Nolte . Translated from the Russian by Ellen Greifer. Muster-Schmidt, Gleichen / Zurich 2008, ISBN 978-3-7881-2032-0 . (Russian original edition: Жертвы ненависти. Холокост в СССР, 1941-1945 гг. - Schertwy nenawisti. Cholokost w SSSR 1941–1945 “, Moskva 2002, review H-Soz-u-Kult , October 24, 2008).

- Frank Grüner: Patriots and Cosmopolitans - Jews in the Soviet State 1941–1953. Böhlau, Cologne / Weimar / Vienna 2008, ISBN 978-3-412-14606-1 (At the same time dissertation under the title: The end of the dream of the Jewish Soviet man? At the University of Heidelberg , 2005).

- Josef Meisl: Haskalah. History of the Enlightenment Movement among the Jews in Russia. Newly edited by Andreas Kennecke. Verlag von Übigau, Berlin 2009, ISBN 978-3-942047-00-5 (improved new edition of the original edition from 1919).

- Bernard Dov Weinryb : Recent Economic History of the Jews in Russia and Poland. Part: 1. Economic life d. Jews in Russia a. Poland from d. 1st Polish part until the death of Alexander II (1772–1881). Marcus, Breslau 1934. 2., revised. u. exp. Ed., Olms, Hildesheim 1972.

- Armin Pfahl-Traughber : Anti-Semitism in Russia . In: Christoph Butterwegge , Siegfried Jäger (Ed.): Racism in Europe . 2nd edition, Bund-Verlag, Cologne 1993, ISBN 3-7663-2467-5 , pp. 28-45.

- Louis Rapoport: hammer, sickle, star of David. Persecution of Jews in the Soviet Union. Ch. Links Verlag, Berlin 1992, ISBN 978-3-86153-030-5 .

Individual evidence

- ^ Walter Homolka and Esther Seidel: Not through birth alone - Conversion to Judaism , Frank & Timme, Berlin, 2006, ISBN 978-3-86596-079-5 , p. 73

- ↑ IM Aronson: Troubled Waters. The Origins of the Anti-Jewish Pogroms in Russia, Pittsburgh 1990, pp. 59ff

- ↑ IM Aronson: Troubled Waters. The Origins of the Anti-Jewish Pogroms in Russia, Pittsburgh 1990, p. 167ff

- ^ Gunnar Heinsohn: Lexikon der Genölkermorde, Hamburg 1998, p. 202.

- ↑ Orlando Figes: A People's Tragedy - The Russian Revolution 1891-1924, Pimlico, 1997, p. 679

- ^ Yuri Slezkine : The Jewish Century (from the English by M. Adrian and B. Engels), Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2006, ISBN 978-3-525-36290-7 .

- ^ Russian censuses in 1939

- ↑ Heinz Eberhard Maul, Japan und die Juden - Study of the Jewish policy of the Japanese Empire during the time of National Socialism 1933-1945 , dissertation Bonn 2000, p. 161. Digitized . Retrieved May 18, 2017.

- ↑ Palasz-Rutkowska, Ewa. 1995 lecture at Asiatic Society of Japan, Tokyo; "Polish-Japanese Secret Cooperation During World War II: Sugihara Chiune and Polish Intelligence," ( Memento from July 16, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) The Asiatic Society of Japan Bulletin, March – April 1995.

- ↑ Gennady Kostyrčenko: Tajnaja politika Stalina. Vlast 'i antisemitizm. Novaya versija. Čast 'I. Moscow 2015, pp. 304-306.

- ↑ See also Ilja Altmann: The fate of the "Black Book". In: Ilja Ehrenburg, Wassili Grossman: The Black Book. The genocide of the Soviet Jews. German by Ruth and Heinz Germany. With contribution by Ilja Altman…, Rowohlt, Reinbek bei Hamburg 1994, pp. 1063-1084.

- ↑ Hellmuth G. Bütow (ed.): Country Report Soviet Union, Series Volume 263 of the studies on the history and politics, Federal Agency for Civic Education, 2nd updated edition, Bonn, 1988

- ↑ Censuses in Russia 1939-2010

- ^ Stephan Stach: East German dissidents and the memory of the Shoah. In: Dossier # 58: “Le renouveau du monde juif en Europe centrale et orientale”, Regard sur l'Est, online ( Memento of March 4, 2016 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Jewish Telegraphic Agency: New Russian patriarch reaches out to Jews , February 4, 2009, accessed June 4, 2017

- ↑ Russian Orthodox Church: Patriarch Kirill honors the memory of victims of fascism in Yad Vashem Memorial in Jerusalem , November 12, 2012, accessed June 4, 2017

- ↑ Pravmir.com: Patriarch Kirill, leaders of Russian Jews discuss problems of fighting extremism , October 29, 2016, accessed June 4, 2017

- ↑ By Putin's grace, Jewish General, March 17, 2016

- ↑ Ben Schreckinger: The Happy-Go-Lucky Jewish Group That Connects Trump and Putin, in: Politico of April 9, 2017 (English)