Ilya Grigoryevich Ehrenburg

Ilja Grigoryevich Ehrenburg (occasionally also transcribed as Erenburg ; Russian Илья́ Григо́рьевич Эренбу́рг ; * January 14th ( Julian calendar ) / January 26th ( Gregorian calendar ) 1891 in Kiev , Russian Empire ; † August 31, 1967 in Moscow , Soviet Union ) was a Russian writer and journalist.

He is one of the most productive and distinguished authors in the Soviet Union and has published around a hundred books. Ehrenburg is primarily known as an author of novels and as a journalist , especially as a reporter and partly also a propagandist in three wars ( First World War , Spanish Civil War and, above all, Second World War ). His propaganda articles during World War II subsequently sparked heated and controversial debates in the Federal Republic of Germany , especially in the 1960s. The novel Thawgave the name to a whole epoch of Soviet cultural policy, namely the liberalization after the death of Josef Stalin ( thaw period ). Ehrenburg's travel reports also met with a great response, but above all his autobiography People Years Life , which can be considered his best-known and most discussed work. Of particular importance was jointly produced by him with Vasily Grossman published Black Book about the genocide of Soviet Jews , the first major documentation of the Shoah . Ehrenburg also published a number of volumes of poetry.

Life

Jewish origin, revolutionary youth

Ehrenburg was born into a middle-class Jewish family; his father Grigori was an engineer. The family did not obey any religious rules, but Ehrenburg learned the religious customs from his maternal grandfather. Ilja Ehrenburg never joined a religious community and never learned Yiddish ; he saw himself as a Russian and later as a Soviet citizen and wrote in Russian, even during his many years in exile. But he attached great importance to his origins and never denied that he was Jewish. In a radio speech on his 70th birthday, he said: “I am a Russian writer. And as long as there is only one anti-Semite in the world, I will proudly answer the question about nationality: 'Jew'. "

As a fourteen-year-old student, Ehrenburg got caught up in the events of the Russian Revolution of 1905 .

In 1895 the family moved to Moscow, where Grigori Ehrenburg got a position as director of a brewery. Ilya Ehrenburg attended the renowned First Moscow High School and met Nikolai Bukharin , who was in a class two years above him; the two remained friends until Bukharin's death during the Great Terror in 1938.

In 1905 the Russian Revolution hit schools too; the high school students Ehrenburg and Bukharin took part in mass gatherings and witnessed the violent suppression of the revolution. The following year they joined an underground Bolshevik group. Ehrenburg illegally distributed party newspapers and gave speeches in factories and barracks. In 1907 he was expelled from school, in 1908 he was arrested by the tsarist secret police, the Ochrana . He spent five months in prison, where he was beaten (some of his teeth were broken off). After his release he had to stay in different provincial towns and tried again to make Bolshevik contacts there. Finally, in 1908, his father succeeded in obtaining a “spa stay” abroad because of Ilja Ehrenburg's poor health; he left bail for it , which later expired. Ehrenburg chose Paris as the place of exile, according to his own statements, because Lenin was staying there at the time. He never finished his schooling.

La Rotonde - the life of the bohemian

Ehrenburg visited Lenin in Paris and initially participated in the political work of the Bolsheviks. But he soon took offense at the numerous disputes between the factions and groups, but above all the lack of interest of the Russian exile community for life in Paris. His lover and party member, the poet Jelisaveta Polonskaya , put him in contact with Leon Trotsky , who was in Vienna at the time. But Ehrenburg was deeply disappointed in Trotsky. In his memoirs he reports that he judged the works of Ehrenburg's literary role models at the time, the Russian symbolists Valeri Brjussow , Alexander Blok , and Konstantin Balmont as decadent and described art in general as secondary and subordinate to politics. (However, Ehrenburg refrains from naming Trotsky, who only appears as “the well-known social democrat Ch.”) He was deeply disappointed and returned to Paris. There he and Polonskaya produced a magazine called People from Yesterday , which contained satirical caricatures of Lenin and other leading socialists, and in this way made himself thoroughly unpopular. Soon afterwards he left the Bolshevik organization and since then has remained independent until the end of his life.

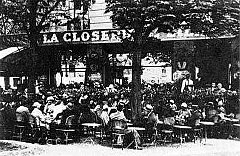

Ehrenburg began to write poetry and published his first volume of poetry in the tradition of the Russian symbolists as early as 1910. His center of life in the years before the First World War was the cafés in the Quartier de Montparnasse , then well-known meeting places for artists: the “ Closerie des Lilas ”, but especially “ La Rotonde ”. It was there that Ehrenburg met the great modern artists, with whom he began lifelong friendships. The painters Amedeo Modigliani , Pablo Picasso , Diego Rivera and Fernand Léger were among his closest friends; he has been portrayed by them several times. Maximilian Woloschin and Max Jacob were his closest confidantes among the writers .

During this time, Ehrenburg lived off his father's payments and odd jobs, including as a tour guide for other Russian exiles; with writing he could not earn any money, although he created several volumes of poetry and translations of French poetry ( Guillaume Apollinaire , Paul Verlaine , François Villon ). His poetry received increasingly positive reviews, including by Bryusov and Nikolai Gumilev , but they could not be sold - on the contrary, he spent money to self- publish them. After his temporary departure from politics, he was at times strongly inclined to Catholicism , admired the Catholic poet Francis Jammes , whose poems he translated into Russian, and also wrote Catholic poems himself, for example on the Virgin Mary or Pope Innocent XI. but he never converted.

At the end of 1909 he met the medical student Jekaterina Schmidt from Saint Petersburg . The two lived together in Paris and had a daughter in March 1911, Ilya Ehrenburg's only child, Irina . In 1913 they separated again, with Irina staying with Jekaterina Schmidt; but they seem to have got on well later on, too, and together they brought out an anthology of poems after they separated.

War, revolution, civil war

At the beginning of the First World War , Ehrenburg volunteered to fight for France , but was rejected as unfit. Since money transfers from Russia were no longer possible, his economic situation worsened and he kept himself afloat with loading work at the train station and writing. In 1915 he began to write as a war correspondent for Russian newspapers, especially for the Petersburger Börsenzeitung . His reports from the front, including from Verdun , described mechanized war in all its horror. He also reported on colonial soldiers from Senegal , who were forced into military service, and thus negotiated a problem with the French censorship.

The news of the February Revolution in 1917 moved Ehrenburg, like many other emigrants, to return to Russia. In July he reached Petrograd, as St. Petersburg was now called, via England, Norway, Sweden and Finland. He experienced the dramatic events of 1917 and 1918 first there, then in Moscow. Ehrenburg wrote incessantly, poems, essays and newspaper articles. The lingering atmosphere of violence shocked him; above all he did not think much of the Bolsheviks and repeatedly mocked “God” Lenin and his “high priests” Zinoviev and Kamenev . A volume of poetry, Prayer for Russia , made him known in which he compared the storming of the Winter Palace, the decisive blow of the October Revolution , with rape.

Ehrenburg got to know the futurists and suprematists who dominated the cultural life of the early Soviet years, especially the poet Vladimir Mayakovsky . But he made friends with Boris Pasternak , whose poetry he admired all his life. During this time he made a name for himself with numerous poetry readings in Moscow cafés and pubs; Alexander Blok makes a statement in a diary note that Ehrenburg makes the most caustic mockery of himself and is therefore all the rage among young people.

In the autumn of 1918 Ehrenburg traveled to Kiev on adventurous routes and stayed there for a whole year. During this time, the city changed hands several times: The Germans, Symon Petljura's "Directory of the Ukrainian People's Republic", the Red Army and Denikin's White Army replaced each other as masters. During the rule of the Bolsheviks Ehrenburg published a volume of poetry and worked as a commissioner for the aesthetic education of criminal youth, whom he tried to help with socio-educational measures, literacy, theater groups, etc. He also joined a group of poets, the most important member of which was Ossip Mandelstam . At this time he met the art student Lyuba Mikhailovna Kosintseva and married her soon after; almost at the same time he began a love affair with the literature student Jadwiga Sommer. During his long marriage, Ehrenburg had frank love stories with other women throughout his life. At first he saw Denikin's rule rather optimistically; he gave poetry readings with the Prayer for Russia and wrote a series of anti-Bolshevik articles in the magazine Kiewer Leben (Kiewskaja Schizn) , which were strongly influenced by a mystical Russian patriotism. But during this phase, Russian anti-Semitism soon reached a climax. Ehrenburg wrote about it too and barely escaped a pogrom . The anti-Semitic riots left a strong mark on him and had a lasting influence on his position on the Soviet Union and the revolution.

In 1919 the Ehrenburgs withdrew with Jadwiga Sommer and Ossip and Nadeschda Mandelstam , again on adventurous routes and repeatedly exposed to anti-Semitic attacks, to Koktebel in the Crimea , where Ehrenburg's old friend from Paris, Maximilian Woloschin, had a house. Mandelstam, whom Ehrenburg greatly admired, became his close friend. They were starving - only Jadwiga Sommer had a paid job, the others were occasionally able to contribute food. In Koktebel, Ehrenburg tried, as he writes in his autobiography, to process the experiences of the stormy last years. He now regarded the revolution as a necessary event, even if he was repulsed by its violence and its rule by decree.

Finally, in 1920 the Ehrenburgs returned to Moscow via Georgia . After a few days, Ehrenburg was arrested by the Cheka and accused of spying for the white General Wrangel . It was probably Bukharin's intervention that led to his release. Now he worked for Vsevolod Meyerhold , the great theater man of the revolution, and was in charge of the children's and youth theater section. In Human Years of Life , he later described his collaboration with the clown Wladimir Leonidowitsch Durow and the animal fables that he put on stage with trained rabbits and other animals. The Ehrenburgs experienced this period under war communism in great poverty, food and clothing were difficult to obtain. They finally managed to get a Soviet passport in 1921, and Ilya and Ljuba Ehrenburg returned to Paris via Riga, Copenhagen and London.

The independent novelist

After a 14-day stay, Ehrenburg was deported to Belgium again as an undesirable foreigner. The Ehrenburgs spent a month in the seaside resort of La Panne . During this time Ehrenburg wrote his first novel, the baroque title of which begins: The Unusual Adventures of Julio Jurenito […]. In this grotesque story he processed his experiences with war and revolution and sat down with his biting satire on all warring powers and peoples, but also on the Bolsheviks between all stools. The book was printed in Berlin in 1922 and was published in Moscow in early 1923 with an introduction by Bukharin; soon it was translated into several languages. It was also Ehrenburg's first work, which he held in high esteem until the end of his life and included in his various editions.

Since Paris was closed to him, Ehrenburg now moved to Berlin, where at that time several hundred thousand Russians of all political shades lived and Russian-language publishers and cultural institutions flourished. He spent a good two years there. During this time he was extremely productive: He wrote three other novels, Trust DE , Life and Death of Nikolai Kurbow and Die Liebe der Jeanne Ney , all of which appeared both in Berlin and, in each case with a delay, in the Soviet Union, although they, similar to Julio Jurenito , in no way represented a party position, furthermore a series of short stories ( 13 pipes , improbable stories, etc.). His preferred publishing house at the time was Gelikon , managed by Abram and Wera Vishnyak - Ehrenburg also had a brief love affair with Wera Vishnyak in 1922, while his wife was flirting with Abram Vishnyak.

Ehrenburg also published a number of volumes of essays in Berlin and, together with El Lissitzky, began an ambitious trilingual magazine project that implemented constructivist and suprematist ideas in terms of content and design , but was short-lived. He wrote about Kazimir Malevich and Lyubov Popova , Vladimir Tatlin and Alexander Rodchenko ; Le Corbusier , Léger and Majakowski supported the magazine. Finally he developed an extensive literary criticism . He reviewed new literature from the Soviet Union in the Russian-language Berlin magazine Neues Russisches Buch and published portraits of contemporary authors ( Anna Akhmatova , Andrei Bely , Alexander Blok, Boris Pasternak, Sergei Jessenin , Ossip Mandelstam, Vladimir Mayakovsky, Marina Tsvetaeva , Isaak there and in books) Babel , etc.). His “bridging function” between the Soviet Union and western countries was also reflected in the visits of Bukharin, Mayakovsky, Pasternak and Tsvetaeva to Ehrenburg in Berlin; he arranged visa matters and publication opportunities for his colleagues in western countries.

At the beginning of 1924, Ehrenburg and his wife visited the Soviet Union for a few months. He adopted his daughter, the now thirteen-year-old Irina, who lived in Moscow with her mother and her husband Tichon Sorokin, and arranged for her to go to school and university in Paris; He also obtained a French visa for his three older sisters. During this and his next stay in 1926, he experienced the consequences of the New Economic Policy (NEP), which he was extremely skeptical of. In the spring of 1924 the Ehrenburgs returned to Paris via Italy, where the immigration police no longer objected to Ilja Ehrenburg.

In Paris he processed the social upheavals of the NEP in the novels Der Raffer (German also: Michail Lykow ) and In der Prototschni-Gasse (German: Die Gasse am Moskaufluss or Die Abflussgasse ). It was very difficult to publish these books in the Soviet Union. His first novels had received positive reviews as well as a number of very negative reviews, especially in the magazine of the “proletarian” writers Auf dem Posten (“Na Postu”), which labeled him a homeless, anti-revolutionary intellectual. These problems reached their climax with the novel The Moving Life of Lasik Roitschwantz , the publication of which the Soviet media flatly rejected.

Another series of novels came into being at the end of the twenties: semi-documentary stories about the conflicts of interest in capitalism, for which Ehrenburg did extensive research. He published it under the title Chronicle of Our Days . The focus was on well-known business people such as André Citroën , Henri Deterding , Ivar Kreuger , Tomáš Baťa and George Eastman , who in most cases were named and provided with biographical details. But even these novels could only appear in greatly abridged form in the Soviet Union and also involved Ehrenburg in litigation. Despite his enormous output, he did not succeed in earning a semi-stable living; Royalties were sparse, the lawsuits cost money, and the film adaptation of Jeanne Ney also brought little.

A series of articles that appeared in the Soviet magazine Krasnaja Now after traveling through Poland and Slovakia was more successful . Ehrenburg summarized these and other travel reports from recent years in the volume Visum der Zeit , which Kurt Tucholsky enthusiastically discussed in his Weltbühne column “On the night table”. He also continued his cultural mediation efforts: in 1926 he gave lectures on French film in Moscow, where he was also able to publish a film book (with a cover design by Rodchenko); An illustrated book with his own snapshots from Paris, designed by El Lissitzky, was published there in 1933. An ambitious anthology of French and Russian literature, compiled with his friend Owadi Sawitsch , under the title We and She , however, was not allowed to be published in the Soviet Union - according to Rubenstein's assumption because it also contained some harmless contributions by the already disgraced Trotsky.

Taking sides: advanced literature, anti-fascism

Ehrenburg visited Germany twice in 1931 and thereafter wrote a series of articles for the Soviet press expressing deep concern about the rise of National Socialism . In the face of this threat, he believed he had to take sides: for the Soviet Union, against fascism . For him, this included renouncing any fundamental public criticism of the political course of the Soviet Union. In his autobiography, he wrote: “In 1931 I understood that the soldier's lot was not that of the dreamer and that it was time to take his place in the ranks of the fighting. I did not give up what was dear to me, I did not move away from anything, but I knew: it means living with clenched teeth and learning one of the most difficult sciences: silence. "

Ehrenburg soon received the offer to write as a special correspondent for the Soviet government newspaper Izvestia . After the first articles appeared, he toured the Soviet Union in 1932. He went to the major construction sites of the first five-year plan , especially Novokuznetsk , where a huge steel mill was being built under extremely difficult conditions . This time Izvestia paid for the cost of the trip , which enabled him to hire his own secretary in Moscow, Valentina Milman. Back in Paris, Ehrenburg wrote the novel The Second Day , in which he celebrated Novokuznetsk's achievement; however, he had great difficulty getting the book published in the Soviet Union - it was still not considered positive enough by the media. Only after he had sent a few hundred numbered copies printed at his own expense to the Politburo and other important persons did the novel find acceptance in 1934, albeit with numerous deletions.

In the next few years Ehrenburg wrote a large number of articles for Izvestia , whose editor-in-chief was taken over by his friend Bukharin in 1934. He usually dictated current reports over the phone or transmitted them by telex . He reported on the attempted coup on February 6, 1934, the Popular Front in France, the Austrian Civil War , and the referendum in the Saar area . The tenor of these activities was always the warning of the danger of the rising fascism. In addition, there were numerous literary-critical and cultural-political articles in which Ehrenburg continued to defend Babel, Meyerhold, Pasternak, Tsvetaeva, etc., against the increasing fire from the later supporters of Socialist Realism .

He also defended literary modernism and its representatives in the Soviet Union at the First All Union Congress of Soviet Writers in Moscow in 1934, to which he traveled with André Malraux . Although this congress declared the doctrine of Socialist Realism binding, Ehrenburg derived considerable hopes from the appearances of Bukharin, Babel and Malraux at the congress. He then wrote, presumably together with Bukharin, a letter to Stalin in which he proposed to found an international writers' organization to fight against fascism, which should renounce strict demarcation and unite all important writers - a kind of literary popular front policy .

In 1935, Ehrenburg, together with Malraux, André Gide , Jean-Richard Bloch and Paul Nizan , prepared a major international writers ' congress that corresponded to this idea: the International Writers' Congress in Defense of Culture in June 1935 in Paris. In addition to those mentioned, the participants included Tristan Tzara , Louis Aragon , Aldous Huxley , Edward Morgan Forster , Bertolt Brecht , Heinrich Mann , Ernst Toller and Anna Seghers ; Pasternak and Babel came from the Soviet Union (they were their last trips abroad). The impressive congress was, however, overshadowed by two events: After André Breton hit Ehrenburg in the face in the street in response to a highly polemical article by Ehrenburg against the French Surrealists , he insisted on expelling Breton from the congress; the seriously ill René Crevel tried to mediate and committed suicide after the attempt failed. And by “congress direction” Malraux and Ehrenburg tried to prevent the case of Victor Serge, who was arrested in the Soviet Union, from being dealt with, albeit with limited success.

Spanish Civil War, Great Terror, Hitler-Stalin Pact

At the beginning of the Spanish Civil War , Izvestia was initially reluctant to send Ehrenburg to Spain - until he left on his own at the end of August 1936. At first he stayed mainly in Catalonia and by the end of 1936 had submitted around 50 articles. But he did not limit himself to the role of war correspondent; he procured a truck, a film projector and a printing press, spoke at meetings, showed films (including Chapayev ), and wrote and printed multilingual newspapers and leaflets. He benefited from his friendly relationship with the leading anarchist Buenaventura Durruti , whom he had already met on a trip to Spain in 1931. Ehrenburg always portrayed Durruti and the anarchists with great sympathy, both then and in his autobiography, despite their divergent political views and loyalties.

In 1937 Ehrenburg traveled a lot in Spain, to all sectors of the front. In February he met Ernest Hemingway and became friends with him. Ehrenburg was also one of the organizers of the second international writers' congress for the defense of culture , which met in July as a "traveling circus" (Ehrenburg) first in Valencia , then in Madrid and finally in Paris. Malraux, Octavio Paz and Pablo Neruda . He continued to report on the war, but did not write anything about the increasing bloody purges of the Communists, for example against the POUM . His biographers assume that Ehrenburg deliberately avoided taking a public position on this issue, also under the influence of the disturbing news of the first Moscow trials . In the same year there was a break with André Gide. Ehrenburg had tried unsuccessfully to persuade him to renounce the publication of his critical report on his trip to the Soviet Union ( Retour de l'URSS ) - Gide's criticism was factually justified, but politically inappropriate because it attacked the only ally of the Spanish Republic. When Gide finally signed an open letter to the Spanish Republic about the fate of arrested political prisoners in Barcelona, Ehrenburg publicly attacked him sharply: he was silent on the murder of the Spanish fascists and the inaction of the French Popular Front government, but charged the Spanish republic, which was struggling for survival .

Right after the fighting over Teruel , Ehrenburg traveled to Moscow with his wife at Christmas 1937 and visited his daughter Irina, who had lived there with her husband Boris Lapin since 1933 . He got right into the height of the Great Terror . Ehrenburg received a visitor's pass for the trial of his friend Bukharin, in which he was sentenced to death. He later wrote: “Everything seemed like an unbearably difficult dream […]. Even now I don't understand anything, and Kafka's trial appears to me to be a realistic, thoroughly sober work. ”How close he himself was to“ disappearing ”later turned out: under the torture Karl Radek had called him a Trotskyist co-conspirator, Babel and Meyerhold should do the same thing a year later. Ehrenburg's appeal to Stalin to allow him to travel to Spain was refused; Against the advice of all his friends, he wrote a second personal letter to Stalin - and was surprisingly allowed to leave the Soviet Union with his wife in May 1938.

In the months that followed, Ehrenburg reported for Izvestia about the last offensive of the Spanish Republic on the Ebro , the exodus of refugees from Spain and the conditions in the internment camps they were sent to in France. With the help of Malraux and other colleagues, he also succeeded in getting writers, artists and acquaintances out of the camps. At the same time, he attacked French politics in the sharpest tones, especially the growing tendency to cooperate with National Socialist Germany , which culminated in the Munich Agreement , and the increasing anti-Semitism in France itself.

From May 1939 his articles for Izvestia were suddenly no longer printed, although his salary was still paid. The reason is probably that the Soviet Union was considering a policy change - from the anti-fascist popular front policy to an alliance with Germany. When the Hitler-Stalin Pact was announced in August , Ehrenburg suffered a collapse. He could no longer eat anything, only consumed liquid food for months, and became very emaciated; Friends and acquaintances feared that he would kill himself. When the German invasion of 1940, the Ehrenburgs were still in Paris - France had not allowed them to leave because of tax disputes. They lived in a room in the Soviet embassy for six weeks, then they could leave for Moscow.

Ehrenburg was not welcome there either; the Izvestia did not print it. At the beginning of 1941 the first part of his novel The Fall of Paris appeared in the literary magazine Snamja ("Banner"), albeit with great difficulty, since any allusion to " fascists " fell victim to censorship (and had to be replaced by " reactionaries "). The second part was blocked for months; only after the German attack on the Soviet Union had begun could the third part appear. In 1942, under completely different political circumstances, Ehrenburg received the Stalin Prize for the work .

War propagandist and chronicler of the Shoah

A few days after the German army marched in, Ehrenburg was called to the editorial office of the Soviet army newspaper Krasnaya Zvezda ("Red Star"). During the four years of the war he wrote around 1,500 articles, almost 450 of them for Krasnaya Zvezda . His texts were also published in a large number of other Soviet media (the first article in Izvestia , which appeared after a two-year break, was titled Paris Under Fascist Boots ). But he also wrote for United Press , La Marseillaise (the organ of Free France ), British, Swedish and numerous other print media and spoke on Soviet, American and British radio. He made frequent visits to the war fronts, sometimes together with American war correspondents (such as Leland Stowe ).

Ehrenburg and his articles enjoyed tremendous popularity, especially with the Soviet soldiers, but also with many allies of the Soviet Union. Charles de Gaulle congratulated him on the Order of Lenin , which he had received in 1944 for his articles of war, and in 1945 awarded him the Officer's Cross of the Legion of Honor .

Documenting the Shoah and the struggle of the Jews played a special role in Ehrenburg's activities during World War II . In August 1941 a large gathering of prominent Jewish Soviet citizens took place in Moscow: Solomon Michoels , Perez Markisch , Ilya Ehrenburg and others appealed over the radio to the Jews of the world to support the Soviet Jews in their struggle. These were the beginnings of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee , which was founded in April 1942.

Together with Wassili Grossman , Ehrenburg began to collect reports on the German massacres of Jews, which were to lead to the world's first comprehensive documentation of the Shoah: the black book on the genocide of Soviet Jews , which was produced with the support of American Jewish organizations (including with the substantial participation of Albert Einstein ) and was scheduled to appear simultaneously in the United States and the Soviet Union. Ehrenburg and Grossman acted as editors and contributed reports themselves. The staff included Margarita Aliger , Abraham Sutzkever , Solomon Michoels and Owadi Sawitsch. Publication in the Soviet Union was particularly important to Ehrenburg because he knew very well about "domestic" anti-Semitism. Parts of the material could appear in Snamja and the Yiddish-language Merder fun Felker collection , but there were increasing problems with Soviet censorship , which viewed reports of Jewish victims and fighters as a nationalistic aberration. Finally, the set , which had already been completed, was destroyed in the course of Stalin's anti-Semitic campaigns in 1948. The Black Book never appeared in the Soviet Union.

Ehrenburg's last war article (“ Enough !”) Was published on April 11, 1945. After that, he was disgraced in Pravda and could not publish any more articles for a month. He had fallen from grace once again (see below ).

In the cold war

In 1945 Ehrenburg traveled through Eastern Europe and to the Nuremberg Trials and published reports about it. He associated high hopes with the end of the war, which, however, turned out to be an illusion, as the first signs of the Cold War soon began. Together with Konstantin Simonow and another journalist, in 1946, shortly after Winston Churchill's famous speech on the Iron Curtain , Ehrenburg went on a trip to the USA as a correspondent for Izvestia . Since he was by far the most experienced Soviet journalist in dealing with Western media, he became a kind of ambassador for Soviet politics. He took the opportunity to see Albert Einstein and talk to him about the publication of the Black Book, and shocked his hosts with the desire to visit the southern states to report on the racial discrimination there - which he was granted. Later, too, he repeatedly defended Soviet foreign policy at press conferences, for example in Great Britain, and in newspaper articles. In 1946, Ehrenburg, like Simonov, was involved in attempts by the Soviet Union to encourage Russian emigrants in Paris who had left their homeland after the victory of the Red Army in the Russian civil war to return to Moscow.

In 1947 Ehrenburg's great war novel Sturm was published , which was initially criticized for the love of a French resistance fighter for a Soviet citizen in the Soviet Union, but was then awarded the Stalin Prize in 1948. A Cold War novel The Ninth Wog was published in 1951 - it was the only book that Ehrenburg abandoned a little later because it was completely artistically unsuccessful. In 1951, work began on an (incomplete) edition of Ehrenburg's works, albeit with bitter battles over the censorship of many books (up to and including the request to delete the Jewish-sounding names of heroes). Ehrenburg was able to use the proceeds to buy a dacha in Novy Ierusalim ( Istra ) near Moscow.

Since 1948, Ehrenburg also played, together with the French physicist Frédéric Joliot-Curie , a leading role in the “Partisans of Peace” (later: World Peace Council ), for whom his old friend Picasso drew the famous dove of peace . Ehrenburg belonged inter alia. among the authors of the 1950 Stockholm Appeal for a Nuclear Weapons Ban, which received millions of signatures around the world. In Stockholm he met his last lover, Liselotte Mehr, who was married to a Swedish politician and who later played an important role in the decision to write the novel Tauwetter and his memoirs. In 1952 he received the Stalin Peace Prize for his work in the peace movement .

Soon after the end of the war, new waves of repression began in the Soviet Union, initiated in 1946 by Zhdanov's campaign against the “droolers of the West”, which was initially directed against writers such as Anna Akhmatova . Ehrenburg kept in contact with Akhmatova and Pasternak and helped Nadezhda Mandelstam, the widow of his friend Ossip Mandelstam, but did not publicly oppose the campaign. Soviet domestic policy soon took an anti-Semitic turn, which was already apparent in the prohibition of the Black Book and which continued with the murder of Solomon Michoels , disguised by a car accident . In terms of foreign policy, the Soviet Union initially advocated the establishment of the new state of Israel , which it recognized as the second state in the world (after Czechoslovakia ).

At the funeral service for Michoels' death in 1948, Ehrenburg praised his inspiring effect on Judaism and also on the Jewish fighters in Palestine . But a little later, on September 21, 1948, he wrote a full-page article for Pravda , presented in response to a (probably fictitious) letter from a Munich Jew who allegedly asked him whether he advised him to emigrate to Palestine. Ehrenburg wrote that the hope of Judaism was not in Palestine but in the Soviet Union. What binds the Jews together is not the blood that flows in their veins, but the blood that the murderers of the Jews have shed and are still shedding; Jewish solidarity could therefore not be national, it was rather the "solidarity of the humiliated and insulted". The article was generally understood as a signal of a Soviet U-turn: a prominent Soviet Jew turned against Zionism in Pravda . It is true that the article had apparently been commissioned by Stalin, but its content certainly corresponded to views that Ehrenburg had previously represented. On the other hand, Ehrenburg knew very well about the growing anti-Semitism in the Soviet Union and above all about Stalin's increasing persecution of Jews, which he avoided mentioning in his text. The article is therefore interpreted as a warning by Arno Lustiger and Joshua Rubenstein, as an attempt by Ehrenburg to curb the euphoria of the Soviet Jews regarding Israel; but it also caused considerable confusion and consternation. Ewa Bérard quotes a statement by the Israeli ambassador: "You are never betrayed as well as by your own people."

In 1949 the campaign against the rootless cosmopolitans followed , in the course of which almost all leading members of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee were arrested and murdered, and finally in 1952 the trial of the doctors' conspiracy . In February 1949, Ehrenburg's texts were suddenly no longer printed. At a mass meeting, Fyodor Mikhailovich Goloventschenko , member of the Central Committee of the CPSU, untruthfully announced the arrest of the "cosmopolitan Ehrenburg". However, with a personal appeal to Stalin, Ehrenburg managed to lift the publication ban after two months. When an open letter circulated among Jewish writers in 1952/1953, which approved the measures against the "murderer doctors" and possibly also called for the deportation of the Soviet Jews to Birobidzhan , Ehrenburg refused to sign despite considerable pressure. Despite repeated requests, he never declared himself ready to support the anti-Semitic campaigns, nor did he comment on the persecution of Jews and opposition activists in the Soviet Union, but wrote the usual hymns of praise for Stalin.

Ehrenburg had become a very well-known person in these years, on the one hand because of his propaganda activities during the war, which had made him very popular, and on the other hand because of his numerous international contacts and appearances. The reputation he gained in this way saved him from Stalinist persecution and at the same time gave his voice considerable weight in the years that followed.

thaw

Stalin died on March 5, 1953, in April the accused of the "medical conspiracy" were acquitted, in June Lavrenti Beria was arrested. A period of uncertainty followed as to where Soviet society was headed. In the winter of that year Ehrenburg wrote his last novel, Thaw . With subdued euphoria, he told of the beginning of spring in a provincial town and, at the same time, of the fall of a bureaucratic factory manager and his wife's love story with an engineer. Stalin's name does not appear, but the doctors' conspiracy and exile in labor camps are incidentally mentioned for the first time in Soviet literature.

The text first appeared in Znamya in April 1954 and immediately met with strong reactions. The title itself was considered dubious, as it made the Stalin era appear too negative as a period of frost; the editors of the paper would have preferred to see “renewal” or “a new phase”. In the literary magazines there were scathing reviews, including by Konstantin Simonow , who accused Ehrenburg of having painted a gloomy picture of socialist society. At the Second Writers' Congress of the Soviet Union in December, Mikhail Scholokhov and Alexander Surkov attacked the novel in the sharpest tones (and with anti-Semitic undertones). Publication as a book was delayed for two years. In 1963, Nikita Khrushchev personally rejected Thaw as one of the works that " illuminate the events connected with the personality cult [...] incorrectly or one-sidedly". But despite the bitter criticism, the book was a great success both in the Soviet Union and abroad, and numerous translations were published. The linguistic image of the romantic title prevailed; Ehrenburg's book signaled the beginning of the thaw period , a phase of liberalization of Soviet cultural policy and the rehabilitation of victims of Stalinist persecution.

In the years that followed, Ehrenburg campaigned intensively for the rehabilitation of the writers who were persecuted and killed under Stalinism. He wrote a number of forewords, including for a volume of stories by Isaak Babel and a volume of poetry by Marina Tsvetaeva ; in the case of Babel's book, he managed to get it published by stating that his friends in the West were urgently waiting for the manuscript that had been announced and promised. He also spoke at memorial events, for example for the murdered Perez Markisch. His reaction to the Nobel Prize that his friend Boris Pasternak received in 1958 for the novel Doktor Schiwago was ambivalent : he refused to take part in measures against Pasternak (such as his expulsion from the writers' association) and publicly emphasized his appreciation for Pasternak, his poetry and Parts of his novel, however, also expressed criticism of the book and accused the West of using it for its purposes in the Cold War.

At the same time, Ehrenburg fought for the publication of Western art and literature in the Soviet Union. The first Picasso exhibition there in 1956 was essentially based on Ehrenburg's work; He was also able to get a book about Picasso published, to which he wrote the preface. He also contributed to the publication of Russian translations by Ernest Hemingway , Alberto Moravia , Paul Éluard and Jean-Paul Sartre . Finally, in 1960, he managed to have Anne Frank's diary appear in Russian, again with a foreword from his hand.

In addition to forewords and newspaper articles, Ehrenburg wrote a number of literary essays , of which The Teachings of Stendhal (1957) and Chekhov , read again (1959), had a great impact. These essays on great authors of the 19th century were understood as commentaries on current cultural policy and therefore called sharp criticism from - in particular the rejection of any form of tyranny, be it ever so benevolently motivated and historically packaged criticism of the dogma of the partiality of Literature caused offense.

Ehrenburg continued to travel extensively: in Chile he met Pablo Neruda , in India Jawaharlal Nehru , and he also visited Greece and Japan. His continued involvement in the peace movement also enabled him to make numerous trips abroad, which he could use to meet Liselotte Mehr. When there was a break between western and eastern participants in the peace congresses due to the revolution and the Russian invasion of Hungary in 1956 , Ehrenburg responded with a call for pluralism within the peace camp.

People years of life

In 1958 Ilja Ehrenburg began working on his autobiography People Years Life . This large-scale work of well over 1,000 pages comprises six books. It contains, among other things, a series of literary portraits of all of his comrades, including many whose books or pictures were still not printed or shown in the Soviet Union; Examples include Ossip Mandelstam , Wsewolod Meyerhold and the painter Robert Rafailowitsch Falk . It also reports on its own attitudes and feelings about the great events of the time, including the purges of Stalin. Private life is largely excluded.

In April 1960 Ehrenburg offered the manuscript of the first volume of Nowy Mir ("New World"), a liberal literary magazine directed by Alexander Twardowski . A long battle began with the censors over numerous passages in the text. Again and again the print was stopped. At first it was mainly about Nikolai Bukharin , whose portrait Ehrenburg could not include in the volume despite a personal appeal to Khrushchev; he only managed to smuggle Bukharin's name into a quote from an Okhrana report from 1907 that contained a list of Bolshevik agitators. The Bukharin chapter wasn't published until 1990. The difficulty increased as the memoirs progressed. The chapter on Pasternak was initially deleted and only made up for after violent protests from Ehrenburg.

Book four contained the description of the time of the Spanish Civil War and the Great Terror under Stalin. A retrospective sentence aroused particular annoyance among the political leaders: “We couldn't even admit a lot to our relatives; only from time to time we shook the hand of a friend particularly tightly, as we were all part of the great conspiracy of silence. ”This implied that many, like Ehrenburg, knew of Stalin's persecution of innocent people and yet had done nothing about it. The “theory of silence”, as it was soon called, met with the most violent criticism, first in Izvestia , then at a large writers' meeting, and finally, on March 10, 1963, in a long speech by Khrushchev himself, which was completely in Pravda was reprinted. Book six about the post-war period up to 1953 could not be published at first because it got involved in the events of Khrushchev's fall; But just as the conservative-repressive-oriented Leonid Brezhnev had consolidated his power, the last book that Brezhnev could afford appeared in 1965.

In 1966 Ehrenburg began with a seventh, incomplete book by Menschen Jahre Leben , on which he wrote until his death. Attempts by Ilya and Ljuba Ehrenburg to publish the completed chapters in official Soviet magazines were unsuccessful. Excerpts appeared in 1969 in the samizdat publication “Political Diary” by Roi Medvedev and many years later, in 1987, in the course of glasnost , in the journal Ogonyok (“Flammchen”); the complete text could not be published until 1990.

Not only in his autobiography, but also in other ways, Ehrenburg continued to strive for the rehabilitation of writers persecuted under Stalinism and tried to work against a repressive cultural policy. He helped Yevgeny Yevtushenko when his poem about Babi Yar was heavily criticized in 1961 for highlighting the Jewish victims; In 1965 he led the first commemorative event for Ossip Mandelstam's work in Moscow; and in 1966 he signed a petition against the sentencing of writers Andrei Sinjawski and Juli Daniel to seven and five years in a labor camp , respectively .

Symptoms of prostate cancer had already appeared at Ehrenburg in 1958, and bladder cancer came later. On August 7, 1967, he suffered a heart attack in the garden of his dacha . Despite urgent requests from both his wife and his lover Liselotte Mehr, he refused to go to the hospital. The writer died on August 31 in Moscow. He is buried in the Novodevichy Cemetery.

Literary work

Ehrenburg's poetry from the years before and during the First World War is almost forgotten today. While the first volumes of poetry only attracted attention from symbolist circles at the time of their publication, this does not apply to the volume “Poems about Eve” or “Prayer for Russia”. Already in the subject matter there was a shift towards the present and the immediate past (war and revolution), in the form of a change to the discursive, to irony, and sometimes to journalism. These traits also shape Ehrenburg's novels, which dominated his artistic work and helped him achieve a breakthrough.

Ehrenburg's numerous novels deal almost entirely with current topics; they can be understood as literary contributions to political and cultural-political debates and have been widely understood as such. He wrote extremely quickly and set great store by prompt publication; he usually concluded his manuscripts with a note on the place and time of their writing.

The novels generally do not obey the norms of a classicist or realistic romantic theory , but often adopt older models, such as those typical of the Enlightenment epic . Especially in the satirical novels of the twenties, journalistic parts, philosophical and satirical excursions are mixed into the narrative; of Julio Jurenito approximately in its complex with Voltaire Candide been compared. Archaic forms of narration are also taken up: fairy tales , gospels , legends , picaresque novels . The characters are often strongly typed; psychology does not play a major role. The most impressive example of this is Ehrenburg's first novel, which today (alongside Lasik Roitschwantz ) is regarded as his most artistically successful book and has received attention to the present day.

Julio Jurenito

→ Main article: The unusual adventures of Julio Jurenito

The satirical novel, which takes place in the years 1913–1921, describes the adventures of a mysterious Mexican, Julio Jurenito, who gathers seven disciples , travels with them through Europe during the First World War, the Russian Revolution and the Russian Civil War, and finally voluntarily goes to his death by walking in a dark park in expensive leather boots and being robbed according to the program. The first-person narrator Ilja Ehrenburg, his first disciple, is also his biographer.

The Julio Jurenito is a parody on the Gospel account, at the same time but also an adventure - and picaresque and reminiscent of Enlightenment models such as Voltaire's Candide . His protagonist pursues the plan to destroy all systems of belief and conviction in the service of a comprehensive self-liberation of mankind and thus fails. The long-term impact of the work has not only contributed to the anarchist tone and the numerous satirical vignettes that target the International Court of Arbitration in The Hague , the Pope, the socialist parties and the Russian Communist Party . Individual scenes of the work leave the satire and take on a pathos-laden, almost prophetic tone. In the eleventh chapter, Jurenito has a poster printed, the text of which begins as follows:

- In the near future the solemn extermination of the Jewish people will take place in Budapest, Kiev, Jaffa, Algiers and many other places. In addition to the popular pogroms popular with the public, the program includes the burnings of the Jews restored in the spirit of the time, the burying of Jews alive in the earth, sprinkling of fields with Jewish blood and all sorts of new methods of "clearing the countries of suspicious elements" etc. etc. etc.

The speech of an anonymous communist, easily recognizable as Lenin , appears prophetic like this prognosis in a chapter that explicitly alludes to Dostoyevsky's legend of the Grand Inquisitor :

- We lead humanity towards a better future. The ones whose interests are thereby harmed disturb us in every way [...]. We have to eliminate these and often kill one to save thousands. Others are reluctant, failing to understand that they are being led towards their own happiness; they fear the difficult road and cling to the miserable shadow of yesterday's homestead. We drive them on, we drive them to paradise with iron rods ...

This passage played a significant role in the fact that Julio Jurenito could no longer appear in the Soviet Union after 1928 - and even in 1962 only without the Grand Inquisitor Chapter.

Satirical prose - "I kept going astray"

In the following years Ehrenburg experimented with various epic forms. In his autobiography he commented on this search process: “After Julio Jurenito, I had the impression that I had already found myself, my path, my subject, my language. In reality I kept going astray, and each new book negated all the previous ones. "

First he wrote a kind of continuation of Julio Jurenito, the satirical novel Trust DE , which describes the physical destruction of Europe and which Jurenito tries to outdo; also a series of short stories based on the idiosyncratic style of Remisow . The next experiment was a crime and gossip novel , Die Liebe der Jeanne Ney , closely based on Charles Dickens ' great realistic novels, with a complicated fable and of “incredible sentimentality”, as Ehrenburg said in retrospect. Here, in place of the revolution and war, which as an unheard of event formed the center of the first novels, came great love, which completely overturned and at the same time ennobled the lives of heroes; Of course, the lover Andrei is both a Bolshevik and a revolutionary, and in his case the overthrow through love and revolution are closely related. The novel was made into a film under the direction of Georg Wilhelm Pabst , but with a happy ending instead of the tragic conclusion by Ehrenburg - his protest as a screenplay co-author was in vain.

This attempt at “romanticism”, as Ehrenburg called it, was followed by a large-scale novel about revolution, civil war and new economic policy (NEP) in the style of French realism, such as Balzac and Stendhal : Der Raffer . An authorial, omniscient narrator who makes numerous comments and classifications is dealing here with a not very likeable hero whose character shows many deficits: the waiter's son Mikhail Lykow from Kiev, the "ripper", who got out in the turmoil of NEP Greed for size gets on the wrong track, embezzles , goes to jail and commits suicide there. The protagonist's actions, thoughts and feelings are described with a high level of epic objectivity : how he saves his brother, the staunch communist Artyom, by pretending to be him in a White Guard raid; but just as he murdered a Kiev citizen because he was happy about the withdrawal of the Red Army. With his often satirical comments, the narrator keeps his distance from the main character and confronts their grandiose self-justifications with his insight into the psychology of Mikhail Lykov. Artyom, on the other hand, appears straightforward, but pale and uninteresting - even his son, who is born in the last chapter, is actually from Mikhail. A central theme of the novel is the demobilization of Soviet society after the years of permanent civil war - and the question of what happens to the excessive emotions and readiness for violence from this phase in the peace years of NEP. The novel closes with a large tableau of the funeral services for Lenin's death and thus the end of the heroic phase of the revolution.

Summer 1925 takes place in Paris. As in Julio Jurenito , Ehrenburg appears as a first-person narrator with many autobiographical features. But the story is about grief and loss: while his wife is on a spa stay, the narrator falls into homelessness. Driveless, penniless and unable to act, he wanders through the panopticon of the big city, the slums, bars and streets. An Italian bar owner, a farce-like revenant of Julio Jurenito, recruits him for a contract murder of an industrial functionary, but Ehrenburg cannot bring himself to pull the trigger. Add to this a trivial romance with the bar owner's girlfriend. The narrative runs in hard cinematic cuts and jumps. The narrator becomes uncertain about reality: all characters turn into literary shadows, all actions into poses, which he reflects extensively on. At last the novel is driving towards a peculiar cathartic conclusion: the last person to guarantee the protagonist's authenticity of feelings, a little girl, dies in the damaged idyll of southern France. But it is precisely this that enables him to leave:

- An empty world, populated with ideas and clothes, is eerie. But there is salvation, the barely visible contour of a distant coast - your hand, a little warmth and simple love. Let's try to get to the coast with it. Yes we try ...

In Prototschni-Gasse , Ehrenburg's next novel, combines social reporting and romanticism. The action takes place in an ill-reputed Moscow district on the Moskva River , where neglected children live in the basement of a house. The house owner, a negative figure in the novel, tries to suffocate them in the dead of winter by blocking the entrances, which only fails by chance. For the most part, however, the book deals with the changeful fates of different residents of Prototschni-Gasse, their living conditions, love stories and attitudes. The narrator steps back from the “Raffer”, the narrative approach clearly approaches a personal perspective. The satire disappears from the narrator's speech, but manifests itself in the construction of the plot, which disappoints the expectations of a tragic ending. Thus the confession of a character in a novel, made with a grand gesture, to have helped with the murder of the children, comes to nothing - the police are clearing out an empty cellar. A protagonist who has been missing for a long time did not go into the water out of disappointed love, as was initially suggested, but traveled to her sister and married a functionary whom she does not love, but who treats her with respect. Finally, a positive character is introduced, the hunchbacked Jew and cinema musician Jusik, who no longer hopes for his own happiness, but wants to help the characters in the novel to be happy.

This figure is a glimpse of the protagonist of Ehrenburg's following novel, The Moving Life of Lasik Roitschwantz . Ehrenburg took up motifs and narrative forms of Julio Jurenito again, in particular the pattern of the picaresque novel. Roitschwantz is a figure related to Schwejk , a philosophizing Jewish tailor from Homel , who loses his business after being denounced and embarks on an odyssey across Europe. He does a number of dubious pursuits to survive - from inventing cheap plan reports to breeding non-existent rabbits in the Soviet Union to being advertised as a pattern of poor nutrition at a pharmacist in East Prussia. Above all, however, he got to know anti-Semitism, beatings and prisons in many countries, from the Soviet Union to Poland, Germany, France and England to Palestine.

Formally, too, this work is close to the Jurenito in some respects , in particular through a dichotomy of the narrative. Because in addition to the story of the story by the authorial narrator, there is the direct and in some cases also experienced speech by the main character. Ehrenburg had got to know Hasidic stories back then , and Lasik Roitschwantz is constantly philosophizing in their style. The German translator of the book, Waldemar Jollos , drew attention to the “linguistic strangeness ” of the protagonist's direct speech: Yiddish, Russian and the jargon of Bolshevism mix with other influences. “The result is a chaos of language, indivisible mixed from all memories and impressions of this frenzied life. But Ehrenburg handles Dadaism, to which Lasik's language is gradually screwing up, with an extraordinary awareness, of course. "

Between “factography” and the novel

At the end of the 1920s, Ehrenburg turned to new forms of prose, characterized by the integration of empirical data and facts: statistics, historical documents, observations, etc. This turn had a strong impact on the form of the novel itself. The works of this phase aimed to consist of elements the documentation , the report , the arguing rhetoric , mythological references , cultural and political allusions as well as the previously tried narrative forms to create a new whole. Ehrenburg was influenced by the “ factography ” as it was propagated around Mayakovsky in the magazine Nowy LEF (“New Left Front of the Arts”) in the late 1920s .

A first attempt in this area was the Conspiracy of Equals , a fictional biography by Gracchus Babeuf . Almost all characters involved are historically documented; Sources are quoted in the novel or even - at least in the German edition - printed in facsimile . Regardless of this, a change between authorial and personal narrative situations dominates the presentation. Large historical overviews alternate with the inner perspective of Babeuf or his opponents Barras and Carnot ; the narrative perspective can attach itself to a police spy or a demonstration march. Ehrenburg repeatedly creates scenes from key events, such as the shock of Babeuf at the first confrontation with the cruel lynching of the “street”. The thematic focus is the exhaustion and decay phase of the French Revolution - and Babeuf's reaction to it: rejection of the reign of terror and instead an attempt to bring out the social content of the revolution in a flash. The intended parallels to the Russian Revolution are obvious, but remain implicit.

The consequences for the novel form at 10 hp extend much further (the title refers to the mass-produced Citroën 10 CV car model, which was widely advertised at the time ). Here Ehrenburg already wrote in the foreword: "This book is not a novel, but a chronicle of our time." The work followed an assembly principle : In seven chapters, including The running belt , tires , gasoline , stock market , trips , the subject is the automobile, circled. In the haunting, critical portrayal of Taylorist assembly line production and the economic-political struggles over rubber and crude oil , biographical passages are embedded that are repeatedly taken up and by no means do without the inner perspective of the characters: from the real capitalists André Citroën and Henri Deterding to fictional worker Pierre Chardain and the nameless rubber pen in Malaya . In the narrator's speech, however, the “main character” of the work, the automobile, takes on mythical traits regardless of all documentary material . It embodies the destructive tendency of capitalist society, not only in production and the stock market, but also in consumption and wish fulfillment.

- The car works righteously. Long before it was born, since it consists of nothing more than layers of metal and a pile of drawings, it is carefully killing Malay coolies and Mexican workers. His labor pains are excruciating. It chops up flesh, blinds eyes, gnaws at lungs, takes away reason. Finally it rolls out of the gate into that world that was called the "beautiful" before it existed. It immediately takes away its old-fashioned calm from its supposed ruler. [...] The car laconically runs over pedestrians. […] It only fulfills its purpose: it is called to exterminate people.

An opening chapter locates the birth of the car in the plans of a fictional inventor who wants to realize the social promises of the French Revolution with the technical means of the car. The narrative thus gains a structure: the hope for technology is thwarted and denied from chapter to chapter; the social and economic reality makes Philippe Lebon's dream end in disaster . A retarding moment alone forms the central fourth chapter with the descriptive title A Poetic Digression , which tells of the failure of a helpless attempt by French car workers to strike. In the Soviet Union, the book could only appear in excerpts, mainly because of its pointed tendency to be critical of technology.

10 PS was the first contribution in a whole series that was titled Chronicle of Our Days . With changing formal solutions, which ranged from the roman key ( The United Front , to the struggle for Ivar Kreuger's match monopoly ) to the report ( Der Schuhkönig , about Tomáš Baťa ), Ehrenburg tried to translate his idiosyncratic variant of “factography” into literary works.

Socialist realism

The second day (1933) was Ehrenburg's first novel to conform to the norms of socialist realism. Like a number of other novels of those years, it belonged to the genre of the construction and production novel (similar to Marietta Shaginjan's hydroelectric power plant ), but also has features of the educational novel (another example is Nikolai Ostrowski's How Steel Was Tempered ). The title alludes to the second day of creation in the Bible , when land and sea were separated - with this, Ehrenburg compares the second day of socialist construction, specifically the construction of a huge steel mill in Novokuznetsk . As in earlier works, the narrative uses Ehrenburg's film techniques: constant cuts from the long shot of the large construction site to a close-up of a person and back, repeatedly interrupted by flashbacks to the lives of individual people. A large part of the book is devoted to the description of the construction and the life paths of all possible participants, whereby the narrator is particularly concerned with the diversity of the process - idealism and compulsion, glorification of work and the numerous work accidents stand side by side.

Only gradually does something like a plot emerge: Volodya Safonov, who has many features of a self-portrait by Ehrenburg, is a disoriented doctor's son and intellectual who studies mathematics in Tomsk . He loses his girlfriend Irina at Kolya Rzhanov, a shock worker in Novokuznetsk, and finally kills himself. The philosophical conflict between the two main characters is that between the bourgeois, pessimistic intellectual and the new man of socialism. Ehrenburg paints the downfall of Safonov with numerous allusions to Dostoyevsky - the fictional character Safonov himself deliberately creates a key scene as a farce-like copy of a scene from the Karamazov brothers . Safonov's and Rzhanov's points of view and arguments stand side by side with remarkable objectivity and each in their own right, but in the plot Safonov is sacrificed for the victory of the new man. An example of Safonov's perspective:

- For example, he doesn't believe that a blast furnace is more beautiful than a statue of Venus. He's not even convinced that a blast furnace is more important than that piece of yellowed marble. […] He does not explain Doctor Faust's boredom from the peculiarities of the period of original accumulation. When spring arrives and the lilacs bloom in the old gardens of Tomsk, he does not quote Marx. He knows that spring came before the revolution. So he doesn't know anything.

With Without a respite , Ehrenburg followed up with another building novel set in the far north of the Soviet Union. Here, however, he renounced formal innovations and used, as in the love of Jeanne Ney , patterns from the Kolportag novel. One of the positive heroes of the novel, the botanist Lyass, is clearly recognizable as an allusion to Trofim Denisovich Lyssenko . After all, skeptical figures also play a role here; this is how a critic of the demolition of valuable old wooden churches has his say. While the second day was fiercely controversial in the Soviet Union for reasons of form and content (especially the haunting description of adverse conditions, conflicts and accidents at work), it was well received without a break . Ehrenburg's biographer Joshua Rubenstein says the book met Stalin's preference for “industrial soap opera”. Ehrenburg did not think much of this work, as he writes in his memoirs; he described it as a kind of leftover recycling for motifs that were left over from the second day .

The fall of Paris (1942), on the other hand, is not about construction, but rather decay. It is about the downfall of "old-fashioned provincial France with its anglers, its rural dancing and its radical socialists " - not only under the onslaught of German troops. The starting point of the plot are the experiences of three former school friends: the painter André, the writer Julien and the engineer Pierre. But the story quickly expands to include other characters and their perspectives, in line with the “novel epopee” of Socialist Realism, including: the corrupt radical socialist politician Tessat - Julien's father - and the liberal industrialist Desser. Ehrenburg designed a panorama of French society from 1936 to 1940. In addition to numerous “mixed” characters, there is a purely positive figure, the communist Michaud, with whom Tessat's daughter Denise falls in love. Often he is far from the scene, his first name, in contrast to those of the main characters, comes far back in the book - in a letter from the Spanish Civil War. Other people appear more typical than this unreal, pale-looking ideal figure, such as Legré, who is no longer able to orient himself since the Parti communiste français and the communist daily L'Humanité were banned and stumbled around blindly in the fog of the “ drôle de guerre ” .

The descriptions of the great strikes of 1936 and the general exodus from Paris in 1940 are impressive. On the other hand, "the Pact" [the Hitler-Stalin Pact ] appears only in a few comments and is neither presented nor discussed. The “wide screen epic” achieved “dizzying editions” in the Soviet sphere of influence. Lilly Marcou regards it as “arduous reading” with “literary weaknesses”, especially clichéd characters in a novel, which admittedly has not lost its documentary value. She can refer to Ehrenburg himself, who wrote in retrospect: "I couldn't find enough nuances, only applied black and white."

thaw

With his last novel Tauwetter (1954) Ehrenburg returned to topics of Soviet society. Thaw takes place in the winter of 1953/1954 in a Russian provincial town "on the Volga". The big historical themes are replaced by a plot reminiscent of Tolstoy's Anna Karenina (this novel is also mentioned in the introduction). The focus is on the marriage of plant manager Ivan Shuravlyov, a cold-hearted bureaucrat, with the teacher Jelena Borisovna. She falls in love with the engineer Dmitri Korotenko; the love story has a happy ending . Shuravlyov, who had postponed the construction of workers' apartments time and again in favor of investing in the plant to fulfill the plan, is dismissed as plant manager after a spring storm has destroyed the old barracks. As with Anna Karenina , this main plot is contrasted with love stories from other people: the electrical engineering student Sonja Puchowa and the engineer Savchenko as well as the doctor Vera Scherer and the chief designer Sokolowski. What drives the novel, however, are the great events in distant Moscow, which take place beyond what is happening in the novel and are only included in the plot in their long-distance effects. The fall of Shuravlyov is paralleled with the end of Stalinism; Wera Scherer has to suffer from the suspicions in connection with the medical conspiracy ; Korotenko's stepfather was arrested during the years of the Great Terror and deported to the labor camp. In the second part of the novel he returns as a decidedly positive figure; Sokolowski's daughter lives in Belgium and Schuravljow uses this in his intrigues against him.

The characters in the book are (with a few exceptions) "realistic mixtures". They are consistently shown both from the outside perspective (narrative report) and from the inside perspective ( inner monologue ), and as much as the book takes sides against the Stalinist bureaucrat Shuravlyov, he is not portrayed as a villain. He appears as an excellent engineer who is committed to intervening in the event of a fire in the plant, but is out of place as a plant manager and has character deficits.

However, three “symbolic counterpoints” are built into the rather simple story, which result in a dense network of references: The severe frost is loosening in parallel with the thawing of the frozen political and personal relationships; The political changes of de-Stalinization and the events of the Cold War are permanently present in the newspaper reading and the discussions of the characters ; and finally, the novel is pervaded by a current art and literature debate. Its main protagonists are two painters: Wladimir Puchow, frustrated, disoriented and often stepping forward with cynical slogans, without conviction but successfully creates commissioned works in the style of socialist realism; the impoverished Saburov paints landscapes and portraits out of inner conviction, but receives no commissions. Allusions to numerous current novels are permanent, the book opens with a “reader debate” in the factory. The climax of the plot, however, is intended for Puchow, i.e. the protagonist, who cannot be given a favorable prognosis: on a spring day in the city park, he sensually experiences the thawing of emotions and structures and finds snowdrops under the ice for the actress who is just now separated from him.

It is this network of references between the season, love, politics and art that made the novel possible to achieve its extraordinary effect.

Journalistic work

Travel pictures

Ehrenburg traveled extensively throughout his life, and a significant part of his journalistic work consisted of travelogues and travel articles. These mostly appeared first in magazines, but were then often collected and published as books.

The most famous collection, Visum der Zeit (1929), contains observations from France, Germany, Poland, Slovakia and others from the 1920s. collected. Ehrenburg paints a picture of the peculiarities of the respective places, societies and cultures - which earned him the accusation of bourgeois nationalism in the Soviet criticism . But as Ehrenburg says in the foreword, he is more interested in snapshots of his time and their reflection in the places, i.e. chronotopes , time-places:

- Spatial patriotism was yesterday. But it remained an empty space, and since it is difficult to live outside the “blindness of passions”, the term “home” was quickly replaced by “present”. We loved her with no less "strange love" than our predecessors, the "fatherland."

Ehrenburg ties reflections on cultural and political questions to the lively descriptions and stories, which often overlap into the literary. His report on Brittany moves from the nature of the country and the customs of the inhabitants to a strike by the anchovy fishermen in Penmarc'h . The title Zwei Kampf alludes to the fishermen's struggle with nature and with the manufacturers - one could live with the first, but not with the second. From Magdeburg , Ehrenburg tells with some horror of the colorful paintwork on the houses and trams that the Bauhaus- influenced building authority director Bruno Taut had promoted, and takes this as an opportunity to criticize constructivist concepts that he himself had recently advocated:

- But art hurts us as soon as it comes into life. […] This is not a style, albeit a bad one, but a raid or a hostile occupation.

In his reports from Poland, Ehrenburg wrote about Hasidic Judaism, which had just inspired his novel The Moving Life of Lasik Roitschwantz . The tone has changed a lot, however: Ehrenburg now describes Hasidism as falling into decline and sharply criticizes the “backward” upbringing of Jewish youth in the cheder . He describes the opening up to a great language and literature as the greatest hope for the Polish-Jewish youth - and for this the Russian offers itself. Ewa Bérard judges that Ehrenburg confirmed anti-Semitic clichés here, and certifies that these contributions are more (Soviet) propagandistic than literary - in contrast to Ehrenburg's “brilliant” articles about Germany.

Time and again, the moment of non-simultaneity plays a decisive role in Visum der Zeit , not only in the reports on Poland, but also in the texts about Slovakia, where Ehrenburg - with sympathy for both sides - the open and hospitable peasant culture and the constructivist intelligence that had spent their youth in huts without smoke traps, placed side by side.

Non-simultaneity is a dominant topic in Ehrenburg's book Spain (1931):

- If you are not only interested in cathedrals in Spain, but also in the life of the living, you will soon see chaos, confusion, an exhibition of contradictions. A wonderful road with a Hispano-Suiza on it - the most elegant automobiles in Europe, the dream of enduring women in Paris, are made in Spain. - Towards the Hispano-Suiza comes a donkey, on the donkey a peasant woman in a headscarf. The donkey is not her own, she only owns a quarter of the donkey: her dowry.

The depiction of the extreme social contrasts in Spain takes up a lot of space here: for example, the poverty of peasants and farm workers in quasi-feudal structures and the wealth of the landowners achieved without consideration. Ehrenburg is particularly interested in dealing politically with these opposites. In the book on Spain, for example, there is a sympathetic short biography of the anarchist activist Buenaventura Durruti and a conversation between the author and him.

But also in this work, above all, the particularities of Spanish culture and society are addressed. Ehrenburg illustrates the “aristocratic poverty” in Spain with this catchy observation from a posh café in Madrid:

- A full, dark-skinned woman offers lottery tickets: “Tomorrow is a drawing!” Another woman brings her a baby. The woman calmly moves an armchair towards her, unbuttons her blouse and begins to breastfeed the little one. It is a beggar. The most elegant caballeros sit at the tables. The "garçons" of the Parisian cafés would rush over the beggar woman like a pack, in Berlin their behavior seemed so inexplicable that one could possibly let them observe their state of mind. Here you can find it quite natural.

Ehrenburg's travel pictures from the twenties and thirties draw a special tension from the repeatedly mentioned certainty that the world described cannot last forever. You fluctuate between premonitions of doom and hope. An elegiac tone of transience dominates the mood of many descriptions.

The black book

At the suggestion of Albert Einstein , the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee began in the summer of 1943 to collect documents about the murder of Jews on the territory of the occupied Soviet Union, which were to be published in a black book. Ehrenburg was appointed chairman of the literary commission formed for this purpose. After calling a. The Yiddish-language newspaper Ejnikejt received an uninterrupted stream of witness reports. Some of them were viewed by the Literary Commission, some by the Committee itself, and a selection was prepared for printing. This led to controversies: the committee forwarded a number of documents to the USA without Ehrenburg's knowledge, which made simultaneous publication in the USA, Great Britain and the Soviet Union considerably more difficult. In the course of this conflict, Ehrenburg withdrew from the editorial office in 1945 and made the parts he had completed available to the committee. At the same time, the procedure for preparing for printing was also controversial. At a meeting of the Literary Commission on October 13, 1944, Ehrenburg advocated the principle of documentation :

- For example, when you receive a letter report, leave off whatever the author wanted to express; perhaps you will shorten it a little, and that is all that I have done on the documents. [...] If a document is of interest, then you have to leave it unchanged, if it is less interesting, you should put it aside and turn to the others ...

Wassili Grossman , who later took over the editing of the Black Book from Ehrenburg, saw the task of the book, however, in speaking on behalf of the victims: "in the name of the people ... who lie underground and can no longer speak for themselves".

Political authorities of the Soviet Union raised more and more objections to the project; the most important of these was that the fate of the Jews was emphasized disproportionately to that of other peoples. In 1947, Grossman managed to complete the set of the book. However, after 33 of the 42 printed sheets had been printed out , the censorship authority Glawlit prevented the continuation of printing and finally had the finished set destroyed. Subsequently, the manuscript of the Black Book served as material for trials against the functionaries of the Jewish Antifascist Committee (but not against the editors Ehrenburg and Grossman) because of nationalist tendencies. It could never appear in the Soviet Union and only in 1980 in an Israeli publishing house (here, however, the reports from Lithuania were missing ). The first complete edition was published in German in 1994. She relied primarily on Grossman's proofs from 1946 and 1947, which Irina Ehrenburg was able to provide.

The black book contains a total of 118 documents, 37 of which were prepared for printing by Ehrenburg. They range from simple letters and diaries from eyewitnesses and survivors to comprehensive accounts from writers based on interviews and other materials. A large part of Ehrenburg's material belongs to the former, to the latter, for example, Oserow's large report on Babi Yar or Grossman's text on the Treblinka extermination camp . Great importance was attached to the naming of dates, names and addresses that were as precise as possible - the names of the German perpetrators could almost always be verified in 1994, as well as almost all information on the dates and figures of the extermination campaigns, as can be seen from the translators' footnotes. The material is structured according to the republics of the USSR: Ukraine, Belarus, Russia, Lithuania, Latvia. Finally, there is a report on Soviet citizens who helped Jews, a section on the extermination camps on Polish soil (which also contains a report on the fight in the Warsaw Ghetto ) and a chapter with statements by the "executioners" who were captured (as the chapter headed) .

The reports capture the stages of National Socialist terror in ever new places : from the registration to the everyday sadism of particularly feared SS or Gestapo men to the well-organized “actions” aimed at total annihilation. The cruel deeds of Latvian, Ukrainian or Baltic German auxiliary police troops or the Romanian authorities in Transnistria are also being recorded - and the censors largely erased the corrected versions because they weakened the "force of the main accusation directed against the Germans". Many attitudes are represented by the reporters: for a long time some could not believe that the National Socialists actually wanted to exterminate the Jews, others knew this early on; some are seized with paralyzing horror, some decide to resist violently.