The unusual adventures of Julio Jurenito

The unusual adventures of Julio Jurenito and his disciples: Monsieur Delhaye, Karl Schmidt, Mister Cool, Alexei Tischin, Ercole Bambucci, Ilja Ehrenburg and the Negro Ayscha in the days of peace, war and revolution in Paris, Mexico, Rome, on Senegal, in Kineshma, Moscow and other places, as well as various judgments of the master on pipes, on death, on love, on freedom, on the game of chess, the people of the Jews, constructions and some other things is the full title of one 1922 published novels by the Russian writer Ilya Grigoryevich Ehrenburg . The Russian original is Необычайные похождения Хулио Хуренито и его учеников: мосье Дэле, Карла Шмидта, мистера Куля, Алексея Тишина, Эрколе Бамбучи, Ильи Эренбурга и негра Айши, в дни Мира, войны и революции, в Париже, в Мексике, в Риме, в Сенегале, в Кинешме, в Москве и в других местах, а также различные суждения учителя о трубках, о смерти, о любви, о свободе, об игре в шахматы, о еврейском племени, о конструкции и о многом ином (. )

This first novel by Ehrenburg is today counted among his most artistically successful works. It has been translated into a number of languages and has been reissued to the present day. In satirical form he deals with the period of the First World War , the October Revolution and the Russian Civil War . The main character is the mysterious Mexican Julio Jurenito, who travels through Europe with seven disciples and finally seeks death in a small Ukrainian town.

The book has experienced an eventful history of text and reception , which is primarily due to its critical examination of the revolution. In addition to the first edition, there are several abridged and defused versions; both German translations are incomplete.

Prehistory and origin

Ehrenburg, then 30 years old, wrote the Unusual Adventures of Julio Jurenito in June 1921 in the Belgian seaside resort De Panne , then known as "La Panne". He had adventurous years behind him, which provided the material for the novel: he had spent the years before the First World War as a bohemian in the Parisian artists' quarter of Montparnasse . He later wrote war reports for a Petersburg newspaper and reported, among other things, on Senegalese soldiers in the French army. In June 1917, on the news of the February Revolution , he traveled to Petrograd and later to Moscow, where he saw the events of the October Revolution. In 1919 he stayed in Kiev, which was successively ruled by German troops , the Bolsheviks , Denikin's White Army and again the Red Army . After an interlude in the Crimea , he returned to Moscow, where he was promptly arrested by the Cheka as a spy . Released after an intervention by his friend Nikolai Bukharin , he worked there in the children's theater section during the period of war communism .

Ehrenburg had already considered and rehearsed his novel project in Kiev. He spent hours improvising stories in verse form for his wife and two friends, sometimes real memories, sometimes imaginary. According to Ehrenburg's memories, the germ of the future novel was the idea "what a good French citizen or a Roman Lazzarone would do if they got into revolutionary Russia." In Moscow in 1921 he made the decision to write the book, but intended for this purpose to travel to Paris, where he wanted to distance himself from the events, but at the same time was looking for the familiar coffee house atmosphere and hoped for a better supply of food and paper. Through Bukharin's mediation, he was one of the first Soviet citizens to obtain a Soviet passport for a “literary business trip”. However, the French state security classified him as an undesirable foreigner, so that Ehrenburg was deported across the Belgian border by the French police .

In La Panne, Ehrenburg worked on the novel every day from early morning until late at night and was finished in just four weeks. In his memoirs he reported that he wrote “out of an inner compulsion”: “I felt as if I wasn't running a pen over a sheet of paper, but rather charging to attack the bayonet.” The book was first published in 1922 by a Russian-speaking Berliner Verlag, Gelikon - since Ehrenburg was closed to Paris, he chose his next residence in Berlin, where at that time there was a very large Russian community in exile.

Work description

The framework

The obscure Mexican Julio Jurenito met the Russian Jew Ilja Ehrenburg, a starving bohemian writer, in a café in Montparnasse in 1913. Ehrenburg becomes Jurenito's first disciple . While traveling through Europe, Jurenito gathered six other disciples around him: the American capitalist Mr. Cool, the Senegalese hotel bellboy Ayscha, the Russian intellectual Alexei Spiridonowitsch Tischin, the French funeral director Delhaye, the Italian thief Ercole Bambucci and the German technical college student Karl Schmidt. In 1914 the "master" embarks on a mysterious journey - as it turns out later, to relax in Mallorca . Infected by the general enthusiasm for war, his disciples also disperse with the outbreak of war. Only Ehrenburg remains in Paris.

The following year, Jurenito appears again in Paris, now as Minister Plenipotentiary of the Fantasy Republic Labardan, to offer France the support of this small state. At a patriotic celebration organized by Jurenito, Jurenito and Ehrenburg meet Ayscha, who lost an arm as a colonial soldier in the war. You can find the trail of Mr. Cool by an aviator arrow with the inscription "Brother, go into heaven!" Cool has now grown a huge war economy enterprise. In 1916 Jurenito traveled with his disciples to Senegal, where they found the seriously ill Tischin, who had been sent there with the Foreign Legion to suppress an uprising and who had shot Aysha's brother in the process. Disenchanted with the reality of the war, the disciples undertake various journeys that are supposed to serve peace. First she takes a trip to Rome to see the Pope . There Bambucci sells amulets , transportable chapels and similar goods for all warring parties on behalf of the Vatican . Visits to the International Court of Arbitration in The Hague and to the socialist delegations of the Second International in Geneva also give rise to satirical exposure. Now the whole group returns to Paris and is arrested there on suspicion of espionage. She is saved from the execution by the chairman of the League for the Research into Doubtful Acts, who turns out to be Monsieur Delhaye. They go to the front as journalists and are taken prisoner by Germany. But here, too, an unexpected reunion saves them: the commanding officer turns out to be Karl Schmidt.

After months in a German prison camp, the United together with Schmidt went to Petrograd and later to Moscow. Jurenito is now quickly changing commissar activities in the revolutionary administration, u. a. in Kineschma , Schmidt becomes a high official and Ayscha receives a management position in the commissariat for foreign affairs. Cool, on the other hand, is locked up in a camp as an exploiter, and Delhaye goes mad because of the events of the October Revolution. Jurenito and Ehrenburg are later arrested by the Cheka and come to Cool in the camp, but Ayscha's intercession gives them all their freedom again. A “recreational trip” to the Ukrainian city of Jelisavetgrad (today Kropywnyzkyj ) follows, where the disciples experience the vicissitudes of the Russian civil war (like the author himself in Kiev). After a visit to the Caucasus , Jurenito and Ehrenburg, back in Moscow, received an audience in the Kremlin with an anonymous "captain" of the Bolshevik government. Karl Schmidt freed her from later re-imprisonment at the Cheka. Jurenito finally decides to stage his own death: in the small town of Konotop , he goes for a walk in his expensive leather boots in the dark park and, according to the program, becomes the victim of a robbery. Before that, he commissioned Ehrenburg to write his biography.

Formal construction

The novel consists of a foreword and 35 chapters. The first eleven chapters describe the disciples' collection, the next eleven their fates in World War I and a further eleven their experiences in revolutionary Russia. Chapter 34 tells of the Master's death. It is a first-person story by the first disciple who shares the name Ilja Ehrenburg with the author. The story thus appears as a (fictional) biography of Jurenito, written by the fictional character Ehrenburg. It is embedded in a rudimentary framework , consisting of the foreword and the last chapter, which includes the occasion and production of the biography as well as a review of the result.

In the chapters, the chronologically progressive report of the first-person narrator alternates with extensive, sometimes full-chapter passages of verbatim speech by the “master” Julio Jurenito, who lectures on numerous topics, in particular love, art, religion, history and politics. These two layers are also clearly differentiated stylistically: the narrator, loyal to the master as a “disciple”, speaks in a consistently ironic tone (also and especially about himself), while Jurenitos prophetic “anecdotes” (as he calls them) in a satirical one Talk about opening up great historical horizons.

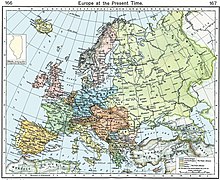

The narrative report covers a precisely defined period from 1913 to 1921, with retrospectives on the biographies of the master and his disciples inserted. The scenes change quickly and suddenly; While Paris is the center of the narrative at the beginning (with trips to Belgium, the Netherlands and Italy), the path of the characters in the last part leads to Moscow again and again. The middle section marks the transition between these two centers of action and contains many large-scale changes of location ( Senegal , Rome , The Hague , Geneva , Verdun , Oberlahnstein , Kowno , Petrograd ).

The gospel according to Ehrenburg

The novel is a clearly recognizable parody of the Gospel and especially the Passion account . Jurenito was born on the day of the Annunciation and, like Jesus, dies the sacrificial death - at the age of 33, as was accepted by Jesus. Jurenito (Хуренито) and Christ (Христос) also have the Russian initial Х in common. Numerous allusions to the Gospels permeate the narrative, from the gathering of the disciples to the so-called “ miracles ” of the master to his denial by the disciple Ehrenburg. The correspondences are also formally clear: the action is repeatedly interrupted by chapters with teachings by Jurenito, which are mostly kept in parable form. Last but not least, Ehrenburg's role as a disciple and biographer of the master is modeled on the authors of the Gospels.

But the parodic treatment of the original is just as clear. Jurenito teaches "nobody and never anything"; he has "neither religious dogmas nor ethical precepts, not even a primitive philosophical system"; he is “a person without convictions”, rather a great provocateur (p. 12f.). His concern, shrouded in mystery, is the destruction of all systems of belief and conviction, which should ultimately lead to the liberation of humanity in the distant future. Ralf Schröder has therefore also referred to this figure as a “black, anarchist messiah” and spoke of a “negative Christology”.

The work of the “master” appears in the novel in a wavering light; various hints in the style of a conspiracy theory stylize him as the secret author of all world-shaking events including war and revolution, while in other places he is characterized as a failing prophet whose hopes are disappointed time and again. And his disciples, with the exception of the biographer himself, are not even aware of their youthfulness: “One idiot calls me: 'Führer', the other: 'Kompagnon', the third: 'Freund', the fourth: 'Comrade', the fifth: 'Patron', the sixth: 'Lord' and you, the seventh, call me 'Master' ”(p. 327), Jurenito complains to Ehrenburg. Jurenito's sacrificial death is by no means motivated by the will to save the world, but rather by excessive boredom in the face of the “non-flying airplane” of the revolution. He justifies it like this: “I have to die properly. It is easy for anyone else: it is enough simply to have convictions that do not correspond to the common ones. But, as you know, I have no convictions ... So I can't die because of an idea. The only hope remains: my boots… ”(p. 328).

Satirical encyclopedia, picaresque novel

Of course, other elements of the text do not fit into the scheme of the Gospel parody. This already applies to the unusually long title, which appears baroque and lists the protagonists , the locations and times of the action, and the hero's teaching subjects. The chapter headings are designed similarly. The erratic action, the renunciation of psychological development and the first- person narration as a narrative form have suggested a different classification to various reviewers and researchers. Erika Ujvary has suggested that the novel should be understood as a modern adaptation of the rogue or fool novel in the tradition of Lazarillo de Tormes or von Grimmelshausen's Simplicissimus . With an interesting reversal, of course, as Holger Siegel adds: Here the fool is not the servant of several masters, but rather the master of several disciples. The reception as a picaresque novel can be based on the repeated fool maneuvers Jurenito, who repeatedly takes the common phrases literally and thus exposes them.

An example: As the representative of the Republic of Labardan, Jurenito asks the French Foreign Minister about his war goals and receives the following reply: “These goals are known to the whole world ... we fight for the right of everyone, even the smallest peoples, to decide their fate, for them Democracy and for Freedom ”(p. 160ff.). Jurenito then sent a declaration of the following to all newspapers, which, unsurprisingly, was not allowed through by the military censors:

- The government of the Labardan Republic cannot remain neutral in the great struggle between barbarism and civilization. From the discussions with the representatives of the Allied Powers, the government of Labardan has gained insight into the lofty goals of the advocates of law. All peoples, even the smallest, will be given the right to decide their fate. The Poles, Alsatians, Georgians, Finns, Irish, Egyptians, Hindus and dozens of other peoples will be freed from the foreign yoke. The oppression of peoples of other races will cease and there can be no more colonies. After all, in despotic Russia, if the allies are victorious, freedom will be introduced. The government and the people of Labardan can no longer remain silent and proudly join the ranks of the fighters for true justice!

After carefully reading official statements, Jurenito is now editing his declaration in the following sense:

- As historians have researched, in Nuremberg lived in the XVII. Century a watchmaker of Labardan citizenship. That is why Nuremberg and all the adjacent areas, including Munich, must fall to Labardan. (P. 162)

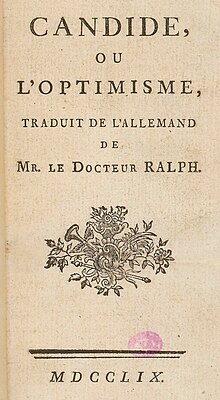

On the other hand, the novel has already appeared to contemporaries as an adaptation of certain satirical novels of the Enlightenment . Voltaire's Candide or optimism in particular is mentioned here again and again. Numerous similarities are cited: the grotesque elements of the plot, the renunciation of probability, the recurring motif of the happy chance rescue at the last second, the satirical narrative attitude , the mixing of narrative and instructive passages with global claims, the teacher-student relationship of the heroes. In fact, Jurenito is a real pangloss (literally: all-linguist, the name of the teacher of Candide), as he masters a very improbable mixture of languages, crafts and sciences. In addition, like the Candide , the novel revolves around a philosophical idea: in this case not, as with Voltaire, around Leibniz 's teaching that this world is the best of all possible worlds, but around the destruction of all norms of belief and conviction, from Christianity to nationalism up to communism , in the service of a utopian idea of human self-liberation. And as with the Candide , the novel's skeptical and ironic attitude towards this idea is characteristic.

Eighth come through the whole world - the fictional characters

Ehrenburg eschews psychological motivation and personal characterization for the protagonists of the novel, especially the “Jüngern”. As in the picaresque novel, these are types that show no inner development, but are reduced to a few features like a woodcut. In doing so, Ehrenburg takes up the scheme of nationality satire, which is part of the traditional inventory of satirical literature, but expands it to include time-related and above all literary features ( literary satire ).

So appears Alexei Tishin as a caricature of the Russian intellectuals in the Dostoevsky Succession: He is a supporter of Merezhkovsky says without pause his life story, especially in the railway (an allusion to the beginning of Dostoevsky's novel The Idiot ) and tormented constantly with questions of conscience around without being able to act. Mr. Cool, on the other hand, is characterized above all by the combination of business acumen, ruthlessness, modern technology, advertising and biblical stability - as the archetype of the American capitalist. Monsieur Delhaye has become a cliché image of the French reindeer with his love of numbers, good food and his stereotypical idioms. Ayscha brings the motif of the child of nature thrown into the European confusion into play, Bambucci appears as the epitome of the anarchic day thief.

The portrait of Karl Schmidt attracted particular attention in the literature : He combines the 'German' characteristics of orderliness, frugality and organizational skills. For the purpose of organizing the whole world, all spiritual foundations are right to him; he confesses that he could very well be a nationalist and a socialist at the same time. Accordingly, he pursues his organizational plans both as a German officer and as a Soviet Commissioner; this includes u. a. the separation of sexuality and child production by means of artificial insemination for the purpose of state planning. In later years Schmidt was seen several times as the archetype of the National Socialist avant la lettre . The following monologue by Schmidt is often cited as evidence:

- Do you think that it is pleasant for me and all Germans to kill? ... No, killing is a very unpleasant necessity. A very dirty occupation without enthusiasm and without joy. ... But there is no other choice. ... Whether one kills a mad old man or ten million people for the benefit of mankind is only quantitatively different. ... That is precisely why I will not hesitate for a moment if it is to the advantage of society to sink all 'Lusitanias' and kill hundreds of thousands of people for the good of Germany tomorrow and for the good of mankind the day after tomorrow. Is it still worth talking about cities, churches and similar things? Although it is of course a shame about them (p. 233f .; the RMS Lusitania was an English steamer sunk by a German submarine, over 1100 deaths).

Schmidt confirms this by immediately having to execute a soldier who wanted to flee to his dying wife: "I understand your feelings ... and would send you to your wife immediately, but this would make the desertions out of hand and reduce the Combat ability of the army lead. That is why in the interest of your children, and if you have no children, in the interest of the children of Germany you will have to die in ten minutes ”(p. 235).

The confrontation of such satirically overdrawn types with the overturning events of the time gives the novel a large part of its tension and comedy . Critics noted that the characters were "torn across the pages of the book as if by a hurricane," they lacked inner coherence and consistency. With this, of course, the compositional principle of the novel is addressed: "This novel ... represents the tremendous effort to combine set pieces of clichés and prejudices into panoramas in order to uncover their fragility when they are put together."

The teachings of Julio Jurenito

The novel's title character is clearly influenced by ideas of Russian constructivism that Ehrenburg played with in the early 1920s. Echoes of Karl Marx (“Obstetrician of History”, p. 13) and Friedrich Nietzsche have also been discovered in his views and behavior; In addition, Ehrenburg has integrated Jurenito's features of his friend, the Mexican painter Diego Rivera , into the biography .

For Jurenito there is neither god nor devil, neither good nor bad, only things and people:

- That's the whole joke that everything exists and yet there is nothing behind it. An old Jean is just dying, and at the same time a new Jean is whining for the first time. It was raining earlier and now it is dry. It swirls, it rotates - that's all (p. 22f.).

The contempt for all systems of belief and conviction extends to art as well. Characteristic of the materialistic turns of Jurenito's lectures , which are occasionally reminiscent of Heinrich Heine , is his response to (of all things) Mr. Cool's “soulful” confession that he loves beauty and art more than anything else in the world: “But I prefer pork chops young peas ”(p. 99).

Jurenito is not satisfied with satirical criticism, but works actively to destroy culture, but more through talking and planning than through action - he describes himself as the "provocateur with the peaceful smile on his lips and the fountain pen in his pocket" ( P. 13). For this purpose and according to this criterion he also chooses his disciples. Mysterious activities - the hero meets with Serbian students and various large industrialists - suggest that Jurenito was instrumental in bringing about the First World War, but such suggestions are repeatedly ironically broken. He's even working on developing new weapons that can kill 50,000 people in one fell swoop. Of course, he lacks the capital to do so, and his plans end up with Mr. Cool, who initially considers them harmful to the war economy and wants to cancel them for a later war against Japan .

But destruction is not Jurenito's ultimate goal: Again and again he speaks of a utopian future for mankind that requires previous destruction. It is the liberation from the shackles of domination, culture and systems that he addresses in recurring images:

- You see: there in the light of the sun hops over the steppe, throwing up its legs, a little colt. Doesn't it express the whole, limitless delight of being? And here in front of this hut howls, its snout raised to the sky and its tail pinched, a dog. Is not all the grief of the earth in him? The people to come will be like that too: They will not enclose their feelings in tanks weighing a thousand pounds (p. 58f.).

And Jurenito symbolizes rule in revolutionary Russia with the parable of the stick: "The stick remains a stick in any hand ... A government without a prison is a nonsensical, perverse term" (p. 299). What follows is the story of the Menshevik and the Bolshevik , who sit together in prison under the tsar and debate - but when the Menshevik wants to continue the debate after the revolution, his old friend remembers that he is holding “the tried and tested millennial cane”, and has him locked in the old cell again. But this is not the goal of the story:

- It will not take years, but epochs, before people realize that it is not a question of who is holding the stick in their hands today, but the stick itself and simply breaks it (p. 300).

But first, according to Jurenito, the trimmings of the stick must be destroyed by means of religion, art and culture. This is the historic mission of the communists . “I beg you: don't decorate your sticks with violets!” Jurenito conjures up a revolutionary examining magistrate who has just sent him to the labor camp (p. 277). An age of unadorned rule, which removes all its justifications, is required to allow the rise of the "kingdom of freedom":

- Mankind is now by no means going to a paradise, but to the hardest, blackest purgatory. A twilight of freedom breaks, as it were. Assyria and Egypt will be surpassed by this new, unheard of slavery. But these galleys will be the preliminary stage, the pledge of freedom ... A freedom that is not nourished with blood but picked up for free as a tip must perish. But remember: I tell you that now, when thousands of hands reach out for the stick and millions of backs lustfully lust for the stick: the day is coming and nobody will need the stick anymore. A distant day! (P. 256).

But the communists are not fulfilling the historic mission assigned to them by Jurenito. His attempts as Soviet Commissioner to abolish art always fail because the revolutionaries also believe in them. This ultimately leads to resignation to the “non-flying airplane” of the revolution and to Jurenito's voluntary walk to his death.

The double Ehrenburg

In Julio Jurenito the author himself appears, namely as a literary figure and narrator . So there is a duplication, the author on the title page puts himself as a character and narrator in the world of novels. The play with this double figure pervades the entire text: numerous autobiographical allusions suggest a unity of author and narrator, which, however, is simultaneously denied by a whole series of improbabilities and even impossibilities. At the same time, this is a game with the fictionality of the literary text itself: it is authenticated as an authentic narrative and at the same time this authenticity is negated time and again. After all, the novel is also part of the art that the protagonist is about to abolish.

The resulting doubts about the reliability of the narrator are reinforced by a series of "modesty topoi": the narrator declares himself unworthy, incapable of grasping the master's teachings, etc. In addition, Ehrenburg repeats himself as a fictional character (like Tischin) proves unable to act, even numb from the course of action - very different from the agile Jurenito. This is especially true of the October Revolution, the days of which the narrator spends alone in his room, which he comments with bitter tirades on himself and on literature:

- I sat in a dark room and cursed my talentless construction. One of the two: either you would have to put in other eyes or take those useless hands away. In front of my window one makes world history now - not with the brain, not with the imagination, not with verse, but with the hands. "Happy whoever visits this world in its fateful hours," said the poet Tyuchev. Why shouldn't I run down the stairs and join in quickly, as long as there is still soft clay and not hard granite under my hands, as long as one can still write the story with bullets and not read the six volumes of a learned German! But I'm sitting in the room chewing a cold chop and quoting Tjuchev. ... Remember, you gentlemen descendants, what the Russian poet Ilya Ehrenburg has dealt with in these only days! (P. 258; referring to the poet Fyodor Ivanovich Tjuttschew , 1803–1873).

On the other hand, the irony of the narrator Ehrenburg does not stop at his "master". The chronicler not only follows Jurenito's actions, his plans for destruction, his “terrible diagrams” and the choice of his disciples with trembling and horror, he also repeatedly denies the confession he made at the beginning: “Master, I will not betray you.” Already in the foreword Jurenito is introduced as follows: “But his image is luminous and vivid. He stands before me, gaunt and wild, in his orange-yellow vest, with the unforgettable green-spotted tie, and smiles quietly. ... May my words now be just as warm as his hairy hands, just as cozy and intimate as his vest, impregnated with the smell of tobacco and sweat ... ”(p. 11f.). And the end of the novel is the return of the narrator to Western Europe, from the “purgatory of the revolution”, into which the master introduced him, to “cozy hell or, if this term should appear unreasonable, to poorly ventilated paradise” ( P. 339). This turns out to be more suitable for him not only for life but also for writing.

As Johanna Döring-Smirnov explains, it is precisely the simultaneous entanglement and non-identity between teaching, writing and poetry on the one hand and life on the other that is a central theme of the novel and in the doubling of the narrative figure becomes tangible. The relationship between claim and reality, literature and life is constantly thematized in the narrator's speech - in the form of the failure of communication.

From the grotesque to prophecy

Some passages and scenes in the novel can hardly be read as satirical, they acquire an enormously pathos-laden , almost prophetic character. In literary work, apocalyptic prognoses are made for reality; the work aims beyond literature towards historical reality. It was precisely these scenes that contributed significantly to the long-term impact of the novel.

In the eleventh chapter of the novel, Julio Jurenito designs a poster , the text of which begins as follows:

- In the near future the solemn extermination of the Jewish people will take place in Budapest, Kiev, Jaffa, Algiers and many other places. In addition to the popular pogroms popular with the public, the program includes the burnings of the Jews restored in the spirit of the time, the burying of Jews alive in the earth, sprinkling of fields with Jewish blood and all sorts of new methods of "clearing the countries of suspicious elements" etc. etc. etc. (pp. 125ff., italics in the original).

Tischin reacts horrified: “Such meanness in the twentieth century!” But Jurenito contradicts: “Very soon, maybe in two years, maybe in five years you will convince yourself otherwise.” In a historical digression he teaches his disciples that humanity is on Always used to respond to catastrophes by slaughtering Jews. “But since the whole of humanity is facing a famine, a plague and a serious earthquake, I can only show an understandable foresight if I have these invitations printed in advance.” Tischin's question as to whether the Jews are not the same people “as we are ", Jurenito counters with a" somewhat childish game ": He asks the disciples whether the yes or the no should be retained as the only word in the language - everyone chooses the yes, only Ehrenburg the no, whereupon the other disciples promptly from him Move away and sit in the other corner. The chapter closes with a grandiose historical lecture by Jurenitos on the subversive power of the Jewish people.

While this scene particularly touched and astonished readers after the Second World War, another scene had more immediate effects. In Chapter 27, Jurenito and Ehrenburg visit the “Captain's Bridge” in revolutionary Moscow and receive an audience with “a certain man… who is always there”, which none other than Lenin can mean. The scene is based on the model of Dostoyevsky's legend of the Grand Inquisitor from the Karamazov brothers , although here in reality: “outside the legend”, as the chapter heading says. The communist gives his creed:

- We lead humanity towards a better future. The ones whose interests are harmed by this disturb us in every way ... We have to eliminate these and often kill one to save thousands. Others are reluctant, failing to understand that they are being led towards their own happiness; they fear the difficult road and cling to the miserable shadow of yesterday's homestead. We drive them forward, we drive them with iron rods to paradise ... (p. 287).

While Lenin himself was not offended by this portrait, it drew criticism from many Soviet press organs. In the new edition from 1962 the chapter had to be omitted completely.

History of publication and reception

Difficult publication in the Soviet Union - Bukharin's foreword

Gelikon had printed 3,000 copies of the book, in May 1922 2,000 of them had already been sold in Berlin. A few specimens were soon brought to the Soviet Union. There the work attracted considerable attention and met with great interest. Shortly after the publication of Julio Jurenito , Ehrenburg was referred to in a Russian review as " the fashion writer", and in 1926, the critic A. Leschnew considered Ehrenburg to be "the most popular and definitely most widely read writer at the moment". There was even a stage version that merged three works by Ehrenburg ( Julio Jurenito , Nikolai Kurbow and Trust DE ), but also massively changed their content. Mr. Cool let himself be carried on his back by the fictional character Ilja Ehrenburg and spurred him on: “Faster, my bourgeois stallion!” Ehrenburg saw her in Kiev in 1924 and protested against the disfigurement of his works, albeit largely unsuccessfully.

But despite the enormous popularity of the novel, its publication in the Soviet Union turned out to be quite difficult, among other things because it got caught up in the lively debates of Soviet literary criticism and cultural policy. In 1922, Ehrenburg sent a copy of Julio Jurenito to his old friend Jelisaveta Polonskaja in Petrograd with the request to find out about the possibilities of publication in Russia. In autumn 1922, all accessible copies of the Gelikon edition were confiscated by the GPU as "dangerous" reading - but the Moscow state publisher Gosudarstvennoje isdatelstwo RSFSR (Gosisdat) had already accepted the book, but now made the additional condition of a commentary foreword. This condition was met by Bukharin , who, as a member of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Russia, had considerable influence; With its foreword, the book was finally published in April 1923 by Gosisdat with an edition of 15,000 copies.

Bukharin wrote: “It is not difficult to determine that the author is not a communist, that his belief in the future order is not overly strong and that he is not exactly passionate about this order. All of which doesn't detract from the fact that the book is a gorgeous satire. The idiosyncratic nihilism and the 'great provocation' point of view allow the author to show a number of ridiculous and repulsive sides of life under all regimes ... This is why the book is funny and interesting, thrilling and clever. ”So he took the book because of it his artistic value and above all his wit in protection against the author's suspicion as politically unreliable - a criticism that he freely admitted.

The criticism in the Soviet Union

Julio Jurenito received destructive reviews, especially from the authors of the Na Postu magazine , who called for a proletarian standpoint in literature. Georgi Gorbachev, for example, wrote in 1924: "Ehrenburg's skepticism and cynicism serves the philistine bourgeoisie, which is rotting in the curvature of the New Economic Policy ." The tone later became even sharper and took on an anti-Semitic tone . In 1926 I. Evdokimov described Ehrenburg in the literary magazine Nowy Mir as an “eternal Jew” and said: “Someone thought that Ehrenburg castigated the bourgeoisie and capitalism in his works ... That is an incomprehensible mistake - Ehrenburg is the most successful embodiment of these Culture ... every sentence of his protest is only dictated by her. "

In contrast, other authors and critics in the debate were extremely positive. Already on June 28, 1922 called Alexander Voronsky in Pravda the Julio Jurenito an "excellent" book that "long ago should have been re-released by our official media"; In 1923, Marietta Schaginjan praised the book's skepticism, which was appropriate for depicting a period of decline or “liquidation”. In 1923, Yevgeny Zamyatin admired Ehrenburg's masterful use of the “European weapon” irony, which was too little respected in Russia, and gave high praise: “He is of course a real heretic (and therefore a revolutionary). A true heretic has the same quality as dynamite: the creative explosion takes the path of greatest resistance. "

The fierce disputes about the “right line” in cultural policy between the “realists” of the “ Russian Association of Proletarian Writers ” (RAPP), the “modernists” around Vladimir Mayakovsky and the “ Left Front of Art ” (LEF) and the so-called. " Comrades ", especially the Serapion brothers , who insisted on the independence of art from politics, often attached themselves to the person of Ehrenburg and especially to Julio Jurenito . What especially the 'comrades' admired, the all-corrosive irony of the book, which also did not spare the new socialist state, was a stumbling block for the RAPP supporters: signs of political unreliability, lack of a positive point of view, gutter literature. This conflict was not initially decided. Ehrenburg's book benefited from the fact that not only Bukharin, but also the first People's Commissar for Education, Anatoly Lunacharsky , and even Lenin himself spoke favorably about the work. In 1924, Lunacharsky criticized Ehrenburg's "lack of principles", but praised his talent, compared him to Heinrich Heine and said: "His skepticism is directed against the values of the Old World, and from this point of view he is in a certain way our ally." And in the memoirs of Nadezhda Krupskaya , Lenin's companion, which appeared in 1926 , she reports: “I remember that, of the contemporary subjects, Ilyich particularly liked Ehrenburg's novel, which described the war. 'You know, this is Ilja Zottelkopf,' he declared solemnly. 'He did it well.' "

But with the implementation of Stalin's cultural policy at the end of the 1920s, such judgments were no longer sufficient. After 1928, Julio Jurenito could not appear in the Soviet Union for 34 years. In 1935, Ehrenburg attempted to do this, but was confronted with a flood of requests for changes and deletions. He rejected this summarily and instead wrote an epilogue that was supposed to put the ideologically questionable parts of the book into perspective. That was not enough: although the epilogue and the announcement of a new edition of the novel appeared in a Soviet magazine, the novel itself was not printed - the time of the Great Terror had begun. The complete edition of Ehrenburg's writings in the 1950s also did not contain Julio Jurenito .

Only in the wake of the thaw , when another edition of Ehrenburg's “Collected Works” began in 1962, the novel was taken into consideration again. Of course, Ehrenburg had to agree to the deletion of the entire chapter The Grand Inquisitor outside of the legend . Bukharin's foreword, which remained a non-person after his execution in the course of the Moscow trials in the Soviet Union, was also omitted. Yet another lively debate about the political evaluation of this early novel ensued; important critics of Soviet literary magazines wanted to accept only those works by the writer that had been written in the spirit of socialist realism (such as The Fall of Paris and Storm ), but still considered the early work to be politically harmful.

Remote effects

The Julio Jurenito was also a great public success outside of the Soviet Union . A German version was published as early as 1923, created by the renowned Tolstoy and Dostoyevsky translator Alexander Eliasberg . The Berliner Tageblatt praised the novel on the occasion of its publication in German: “A man washed in all waters between the Seine and Neva wrote this accusatory book about Europe. The work is brave, clever and superior. ”In 1930 Eliasberg's translation was reprinted by Malik-Verlag . The novel was also published in Spanish in 1923, with new editions in 1928 and 1931; Translations into French, Polish, Czech, Yiddish, Japanese, English, Bulgarian, Dutch, Italian, Portuguese and Hebrew followed.

Ehrenburg became an Izvestia correspondent in the 1930s , and in the 1940s he achieved fame as a war propagandist for the Soviet Union. At times he was perceived as the foreign ambassador of the Stalinist Soviet Union. But the subversive effect of Julio Jurenito continued; it can be seen as a kind of message in a bottle from Ehrenburg's bohemian phase, especially since Ehrenburg never denied or rewrote the novel and always regarded it as his first really successful work. So was Julio Jurenito among Spanish anarchists well known what Ehrenburg's relationship with Buenaventura Durruti greatly favored. Because of his reputation, he was the only Soviet writer who could seriously collaborate with the Catalan anarchists in the Spanish Civil War .

Another example of such remote effects are the experiences of Victor Zorza , who grew up in western Poland in Ukraine and became a well-known writer and journalist in exile in England after the Second World War. Zorza and his family were taken to a labor camp after the Soviet occupation of eastern Poland. After a successful escape, he wandered through the Soviet Union, which was meanwhile invaded by Germany. In the winter of 1941 he learned from a newspaper article that Ehrenburg was staying in Kuybischew (today Samara ). He wandered there and tried to approach the influential war journalist, whose help he was hoping for because he knew Julio Jurenito - he had been one of his favorite books when he was young. He also mentioned this to Ehrenburg. In fact, Ehrenburg helped him escape to England with a Polish unit.

After the Second World War, a friend of George Orwell's , Tosco Raphael Fyvel , rediscovered the novel as a literary work and published his discovery a. a. in the literary magazine The Month . And again, it was above all the contrast between the established Ehrenburg of 1950, which was part of Stalin's foreign policy, and the anarchic early work by the same author that made the discovery so attractive. This pattern accompanied the reception of Julio Jurenito until the end of the Soviet Union.

The author and his work

The satirical-grotesque novel Trust DE , which was written about a year after Julio Jurenito , is a kind of continuation of the book. With the help of an American trust , the protagonist Jens Boot physically brings about what Julio Jurenito had strived for mainly in speeches and symbolic acts: the Fall of Europe (so the subtitle of the novel). And in fact, The Unusual Adventures of Julio Jurenito appear in Trust DE as a “book within a book”: Jens Boot finds Julio Jurenito's biography during a visit to a brothel owned by Mr. Cool in Amiens and reads it. He borrows the "idea" from this book, the justification for his actions: "Now Jens Boot knew why he had given up Europe to annihilation."

While Trust DE leaned on Julio Jurenito in terms of subject matter and style , Ehrenburg looked for new ways in his later novels. In his autobiography he wrote: “After Julio Jurenito , I had the impression that I had already found myself, my way, my subject, my language. In reality, I kept going astray, and each new book negated all of the previous ones. ”At the same time, Ehrenburg emphasized the continuity of life and development in his work, from the famous debut to the panoramic novels in the style of socialist realism:“ Had I didn't write that in 1921, then I wouldn't have been able to write the case of Paris in 1940 either . "

In 1928, Ehrenburg returned to Julio Jurenito's forms and themes in his satirical novel The Moving Life of Lasik Roitschwantz : the travel fable, the picaresque novel, the satire of nationalities. Only here the hero is not a “master” with strong visions, but a knocked-out Jewish tailor from Homel who also philosophizes about God and the world. Ehrenburg also glosses on Julio Jurenito's complicated publication history : Lasik Roitschwantz gives a speech at the Literary Club in Moscow in which he recommends the publication of the novels of the 'companions' despite their unclear position on the Communist Party - of course "with some deafening foreword". "He writes, for example, that Shurotschka has a great love, but we sell him like a hundred pots in the foreword: 'Shurotschka is not Shurotschka, and love is not love, it's all just a back and forth of social classes in fact, a little later Roitschwantz wrote such a foreword to a French colportage novel : "Using the pretext of a clash of the different sexes, he is in truth vigorously scourging the French bourgeoisie, who dances around like crazy between the chandeliers and limousines." Whether Bukharin took offense at this mocking reverence , is unknown. In any case, he did not like Lasik Roitschwantz , as he said in Pravda .

In his autobiography People Years Life (1961–1965), Ehrenburg reiterated his high esteem for his first novel, while he did not hold back with negative judgments about a number of other, later books. He said: “I couldn't write. The book has many unnecessary episodes, it is not smoothly planed, and every now and then one comes across awkward turns of phrase. And yet I love this book. ”And the confusing interplay that the novel engages between art and life, fictional and real history, is reflected again in these memories:“ Of course the book contains all sorts of nonsensical opinions and naive paradoxes; again and again I undertook to fathom the future; I saw some things correctly, in others I was wrong. But on the whole it is a book that I do not renounce. "

Significance in literary history

The Julio Jurenito has received a number of literary influences in it, especially from the classical Russian literature ( Dostoevsky , Tolstoy , Gogol , Chekhov ), but also from the current art and cultural development ( Futurism , Constructivism , Suprematism , acmeism ) and from the Extra-literary newspaper and leaflet language. In the Grand Inquisitor's chapter, for example, Dostoyevsky's model was the godfather, but also poems by Boris Pasternak and writings by Lenin , as Johanna Döring-Smirnov shows. Alexander Blok's poem The Twelve from 1918, which imagines twelve Red Army soldiers under the leadership of Jesus Christ , also had an influence on Julio Jurenito .

However, it has been difficult for all reviewers and literary scholars to classify or locate the novel itself in terms of literary history. In a contemporary review, Vladimir Mayakovsky's drama Misterium Buffo is considered comparable, and Ralf Schröder mentions the influence of Julio Jurenito on Mikhail Bulgakov's novel The Master and Margarita and on Thomas Mann's Doctor Faustus .

To the German translations

Alexander Eliasberg's translation from 1923 is based on the first edition of the novel and is the basis for all German pre-war editions as well as all West German post-war editions of the novel. However, it suffers from the fact that individual sentences, but also longer passages and even two entire chapters have been left out for unclear reasons. For reasons that are just as unclear in the title, the locations “Kineshma” and “Moscow” have been swapped.

In contrast, the GDR edition from 1975 is based on a translation by Maria Riwkin. Riwkin does not make any deletions, but reproduces the version from 1962, which lacks the entire Grand Inquisitor chapter and which also has a number of other changes. After all, Ralf Schröder's afterword to this edition refers to the missing chapter. So there is unfortunately no complete German translation of Julio Jurenito .

expenditure

In Russian language

First edition:

- Gelikon, Berlin 1922.

With a foreword by Bukharin and various text versions:

- Gosisdat, Moscow 1923, 1927.

With a preface by Bukharin and the first "ideological cuts":

- Zemlya i Fabrika, Moscow 1928.

Without the Grand Inquisitor Chapter and the Bukharin Foreword and with numerous other text changes:

- In volume 1 of the nine-volume edition of the collected works, Moscow 1962, pp. 9–233. A scan available on the Internet is based on this version: lib.ru

Complete version:

- In volume 1 of the eight-volume edition of the collected works (Собрание сочинений в восьми томах), Chudoschestwennaja literatura, Moscow 1990, pp. 217–452. ISBN 5-280-01054-5 . The scan is based on this: belolibrary.imhaben.de

Complete version, checked by comparison with the first edition, edited and with commentary by Boris Fresinski:

- In a collection of texts from Ehrenburg's early prose works: Необычайные похождения, Kristall, St. Petersburg 2001, pp. 33–256. ISBN 5-306-00066-5

In German language

In translation by Alexander Eliasberg:

- Welt-Verlag, Berlin 1923.

- Malik , Berlin 1930.

- Kindler, Munich 1967.

- Gloor, Zurich 1969.

- Suhrkamp , Frankfurt 1976, 1990, ISBN 3-518-01455-2

In translation by Maria Riwkin, with an afterword by Ralf Schröder:

- People and World , Berlin (GDR) 1975.

literature

- Gudrun Heidemann: The writing I in a foreign country. Il'ja Ėrenburg and Vladimir Nabokov's Berlin prose from the 1920s. Aisthesis, Bielefeld 2005, ISBN 3-89528-488-2 .

- Boris Fresinski: Феномен Ильи Эренбурга (тысяча девятьсот двадцатые годы). The Ilja Ehrenburg phenomenon (in the 1920s). In the 2001 edition of the novel mentioned above, pp. 5-31.

- Holger Siegel: Aesthetic theory and artistic practice with Il'ja Ėrenburg 1921–1932. Studies on the relationship between art and revolution . Narr, Tübingen 1979, ISBN 3-87808-517-6

- Zsuzsa Hetényi: Enciklopedia otricaniia. Julio Jurenito Ilyi Erenburga . (After a Hungarian version of 1995). Studia Slavica Hungarica Ac. Scient. 45, 2000, 3-4, pp. 317-323.

- Rahel-Roni Hammermann: The satirical works of Ilja Erenburg. VWGÖ, Vienna 1978.

- Ralf Schröder: The starting point of Ehrenburg's work - the anarchist breakthrough idea as a grotesque satyr play in "Julio Jurenito" and "Trust DE". Epilogue in: Ilja Ehrenburg: The unusual adventures of Julio Jurenito / Trust DE Volk und Welt, Berlin (GDR) 1975, pp. 443–461.

- Johanna Renate Döring-Smirnov: On the function of literary satirical elements in Il'ja Erenburg's novel "Chulio Churenito". In: The world of the Slaves. Volume 18, 1973, pp. 76-90.

- Erika Ujvary-Maier (= Liesl Ujvary ): Studies on Ilja Erenburg's early work. The novel "Chulio Churenito". Juris, Zurich 1970.

- Wolfgang Werth : Predictions that have come true - reunion with Ehrenburg's "Julio Jurenito" after half a century . In: Die Zeit , No. 11/1968.

- Jörg Ebding: I.Erenburg: "Chulio Churenito" , as the first section of part 3 (special case Erenburg - disoriented satirical review) in (author himself): Tendencies of the development of the Soviet satirical novel (1919-1931) , Sagner, Munich 1981, ISBN 3-87690-194-4 , pp. 87-99.

Web links

- Russian literary history in individual portraits, Chapter 17 Contemporary judgment of the literary scholar and translator Alexander Eliasberg on Julio Jurenito on Project Gutenberg-DE

- Review of the 1930 English edition by Bernice Whittemore in Outlook and Independent , 23 July 1930

- The real Ilja Ehrenburg? Article by TR Fyvel with an extensive review by Julio Jurenito . In: The Month , 25/1950, pp. 95-98. Fyvel was the literary editor of the London Tribune .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Joshua Rubenstein: Tangled Loyalties. The Life and Times of Ilya Ehrenburg . University of Alabama Press, Tuscaloosa / London 1999. ISBN 0-8173-0963-2 . P. 74.

- ↑ Ilja Ehrenburg: Menschen Jahre Leben , Book 2, Volk und Welt, Berlin 1978, p. 314. Lazzarone can be translated as Tagedieb .

- ↑ Lilly Marcou: We Greatest Acrobats in the World , Structure Taschenbuch Verlag, Berlin 1996. ISBN 3-7466-1259-4 . P. 21ff.

- ^ Ilja Ehrenburg: Menschen Jahre Leben , Book 2, 1978, pp. 417 and 418.

- ↑ The Unusual Adventures of Julio Jurenito . It is quoted here and below from the edition of Malik Verlag from 1930 in the translation by Eliasberg.

- ↑ Schröder, p. 451.

- ↑ See Ujvary 1970, p. 115, the u. a. cites a 1923 review by the Soviet critic Lew Lunz. Lunz was one of the Serapion brothers , who also included Jelisaveta Polonskaya and Zamyatin.

- ↑ Joshua Rubenstein 1999 and Thomas Urban can be cited as examples . Cf. Urban: Ilja Ehrenburg as a war propagandist. In: Karl Eimermacher, Astrid Volpert (Hrsg.): Thaw, Ice Age and guided dialogues. West-Eastern Reflections, Volume 3: Russians and Germans after 1945 . Fink, Munich 2006. ISBN 978-3-7705-4088-4 . Pp. 455-488.

- ↑ So the contemporary Soviet critic D. Gorbow, here quoted from Ujvary 1970, p. 199.

- ↑ Döring-Smirnov, p. 79

- ↑ Ujvary 1970, p. 84

- ↑ See the quote from Krupskaja, which is reproduced in the chapter "Criticism in the Soviet Union".

- ↑ See Fresinski, p. 12.

- ↑ cf. Ujvary 1970, p. 114

- ↑ Rubenstein 1999, pp. 93f.

- ^ Letter of August 20, 1922, edited by the Ehrenburg researcher Boris Fresinski; [1] .

- ↑ Rubenstein 1999, p. 80; Ehrenburg's letter to Polonskaya of November 25, 1922, [2] .

- ^ Translation from Ujvary 1970, p. 118.

- ^ After Ujvary 1970, p. 117.

- ^ Translation from Ujvary 1970, p. 117; see. also Hammermann, pp. 120f.

- ↑ Rubenstein 1999, p. 79

- ^ After Hammermann, p. 128

- ↑ Rubenstein 1999, p. 80; see. Hammermann, p. 120 ff. Emphasis in the original.

- ↑ After Ujvary 1970, pp. 118f.

- ↑ Quoted from Ujvary 1970, p. 122. "Zottelkopf" (Лохматый) was a nickname of Ehrenburg (due to his unruly mane of hair); Lenin ("Ilyich"), Krupskaja and Ehrenburg knew each other from the Russian community in exile in Paris before the war.

- ↑ See Rubenstein 1999, p. 149.

- ↑ Cf. Ujvary 1970, pp. 125–127, which quotes the critic of Literaturnaja Gazeta , A. Metschenko, as an example .

- ↑ Quoted from Schröder, p. 444.

- ↑ See Rubenstein 1999, p. 159

- ↑ See Victor and Rosemary Zorza: A Way to Die - Living to the End , on the Internet at [3] .

- ↑ Ilja Ehrenburg: Trust DE or the story of the fall of Europe . In: ders .: Julio Jurenito / Trust DE , Volk und Welt, Berlin (Ost) 1974, Chapter 24: Jens Boot familiarizes himself with Julio Jurenito's teaching, p. 397ff., Quote: p. 400.

- ^ People Years of Life , Book 3, p. 22.

- ↑ Menschen Jahre Leben , Book 2, p. 419; Ehrenburg alludes to his characterization of Karl Schmidt.

- ^ Ilja Ehrenburg: The eventful life of Lasik Roitschwantz. Rhein Verlag, Zurich / Leipzig / Munich oJ, p. 134f.

- ^ Ilja Ehrenburg: The eventful life of Lasik Roitschwantz. Rhein Verlag, Zurich / Leipzig / Munich oJ, p. 140.

- ↑ Rubenstein 1999, p. 106, quoting Bukharin's Pravda article from March 29, 1928: "Unprincipled, boring, thoroughly wrong in his one-sided literary vomiting."

- ^ People Years of Life , Book 2, p. 417.

- ^ People Years of Life , Book 2, p. 418

- ↑ See Heidemann, p. 232.

- ↑ Fresinski, p. 16