Standard Chinese

Template:ChineseText Standard Mandarin, or Standard spoken Chinese, is the official modern Chinese spoken language used by the People's Republic of China, the Republic of China (Taiwan), and Singapore.

The phonology of Standard Mandarin is based on the Beijing dialect, which in turn belongs to Mandarin, a large and diverse group of Chinese dialects spoken across northern and southwestern China. The vocabulary is largely drawn from this group of dialects. The grammar of Standard Mandarin is standardized to the body of modern literary works written in Vernacular Chinese, which in practice follows the same tradition of the Mandarin group of dialects with some notable exceptions. As a result, Standard Mandarin itself is usually just called "Mandarin" in non-academic, everyday usage. However, linguists use "Mandarin" to refer to the entire group of dialects. This convention will be adopted by the rest of this article.

Standard Mandarin is officially known

- in the People's Republic of China as Pǔtōnghuà (simplified Chinese: 普通话; traditional Chinese: 普通話, literally "common speech")

- in the Republic of China (Taiwan) as Guóyǔ (simplified Chinese: 国语; traditional Chinese: 國語, literally "national language")

- in Malaysia and Singapore as Huáyǔ (simplified Chinese: 华语; traditional Chinese: 華語, literally "Chinese (in a cultural sense) language").

All three terms are used interchangeably in Chinese communities around the world.

History

Since ancient history, the Chinese language has always consisted of a wide variety of dialects; hence prestige dialects and lingua franca have always been needed. Confucius, for example, used yǎyán (雅言), or "elegant speech", rather than colloquial regional dialects; text during the Han Dynasty also referred to tōngyǔ (通语), or "common language". Rime books, which were written since the Southern and Northern Dynasties, may also have reflected one or more systems of standard pronunciation during those times. However, all of these standard dialects were probably unknown outside the educated elite; even among the elite, pronunciations may have been very different, as the unifying factor of all Chinese dialects, Classical Chinese, was a written standard, not a spoken one.

The Ming Dynasty (1368 - 1644) and the Qing Dynasty (1644 - 1912) began to use the term guānhuà (官话), or "official speech", to refer to the speech used at the courts. The term "Mandarin" comes directly from the Portuguese. The word mandarim was first used to name the Chinese bureaucratic officials (i.e., the mandarins), because the Portuguese, under the misapprehension that the Sanskrit word (mantri or mentri) that was used throughout Asia to denote "an official" had some connection with the Portuguese word mandar (to order somebody to do something), and having observed that these officials all "issued orders", chose to call them mandarins. From this, the Portuguese immediately started calling the special language that these officials spoke amongst themselves (i.e., "Guanhua") "the language of the mandarins", "the mandarin language" or, simply, "Mandarin". The fact that Guanhua was, to a certain extent, an artificial language, based upon a set of conventions (i.e., Northern Chinese family of languages for grammar and meaning, and the specific pronunciation of the Imperial Court's locale for its utterance), is precisely what makes it such an appropriate term for Modern Standard Chinese (i.e., Northern Chinese family of languages for grammar and meaning, and the specific pronunciation of Beijing for its utterance).

It seems that during the early part of this period, the standard was based on the Nanjing dialect, but later the Beijing dialect became increasingly influential, despite the mix of officials and commoners speaking various dialects in the capital, Beijing. In the 17th century, the Empire had set up Orthoepy Academies (正音書院, Zhèngyīn Shūyuàn) in an attempt to make pronunciation conform to the Beijing standard. But these attempts had little success. As late as the 19th century the emperor had difficulty understanding some of his own ministers in court, who did not always try to follow any standard pronunciation. Nevertheless, by 1909, the dying Qing Dynasty had established the Beijing dialect as guóyǔ (国语), or the "national language".

After the Republic of China was established in 1912, there was more success in promoting a common national language. A Commission on the Unification of Pronunciation was convened with delegates from the entire country. At first there was an attempt to introduce a standard pronunciation with elements from regional dialects. But this was deemed too difficult to promote, and in 1924 this attempt was abandoned and the Beijing dialect became the major source of standard national pronunciation, due to the status of that dialect as a prestigious dialect since the Qing Dynasty. Elements from other dialects continue to exist in the standard language, but as exceptions rather than the rule.

The People's Republic of China, established in 1949, continued the effort. In 1955, guóyǔ was renamed pǔtōnghuà (普通话), or "common speech". (The name change was not recognized by the Republic of China which has governed only Taiwan and some surrounding islands since 1949.) Since then, the standards used in mainland China and Taiwan have diverged somewhat, especially in newer vocabulary terms, and a little in pronounciation.

After the handovers of Hong Kong [1] and Macau, the term pǔtōnghuà is used in those Special Administrative Regions of the People's Republic of China, and the pinyin system is widely used.

In both mainland China and Taiwan, the use of Standard Mandarin as the medium of instruction in the educational system and in the media has contributed to the spread of Standard Mandarin. As a result, Standard Mandarin is now spoken fluently by most people in Mainland China and in Taiwan. However in Hong Kong, due to historical and linguistic reasons, the language of education and both formal and informal speech remains the local Standard Cantonese but standard Mandarin is becoming increasingly influential.

The advent of the 20th century has seen many profound changes in Standard Mandarin. Many formal, polite and humble words that were in use in imperial China have almost entirely disappeared in daily conversation in modern-day Standard Mandarin, such as jiàn (贱 "my humble") and guì (贵 "your honorable").

The word 'Putonghua' was defined in October 1955 by the Minister of Education Department in mainland China as thus: '普通话就是现代汉民族共同语,是全国各民族通用的语言。普通话以北京语音为标准音,以北方话为基础方言,以典范的现代白话文著作为语法规范'. ("Putonghua is the common spoken language of the modern Han group, the lingua franca of all ethnic groups in the country. The standard pronunciation of Putonghua is based on the Beijing dialect, Putonghua is based on the Northern dialects (ie. the Mandarin dialects), and the grammar policy is modelled after the vernacular used in modern Chinese literary classics.")

Phonology

The standardized phonology of Standard Mandarin is reproduced below. Actual reproduction varies widely among speakers, as everyone (including national leaders) inadvertently introduces elements of his/her own native dialect. By contrast, television and radio announcers are chosen for their pronunciation accuracy and "neutral" accent. Below is the phonology of Standard Mandarin.

Initials

The following is the initial inventory of Standard Mandarin as represented in the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA):

| Bilabial | Labio- dental |

Alveolar | Retroflex | Alveolo- palatal |

Velar | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plosives | p | pʰ | t | tʰ | k | kʰ | ||||||

| Nasals | m | n | ||||||||||

| Fricatives | f | s | ʂ | (ʐ)1 | ɕ | x | ||||||

| Affricates | ʦ | ʦʰ | ʈʂ | ʈʂʰ | tɕ | tɕʰ | ||||||

| Lateral approximant |

l | |||||||||||

| Approximants | w | ɻ1 | j | ɥ | ||||||||

1 /ɻ/ is often transcribed as [ʐ] (a voiced retroflex fricative). This represents a variation in pronunciation among different speakers, rather than two different phonemes.

Corresponding chart in:

- Pinyin

- Zhuyin

- Gwoyeu Romatzyh

For more complete information, showing how initials and finals interact, see this Zhuyin-IPA chart. The vowel sounds in that chart have been verified against the official IPA: site. A table of valid initial and final combinations can also be seen at:

What are traditionally termed retroflex are phonetically not true retroflex articulations. These consonants are, rather, flat apical postalveolar, and thus differ from both palatoalveolar and (true) retroflex consonants (Ladefoged & Wu 1984; Ladefoged & Maddieson 1996:150-154).

The alveolo-palatal consonants /tɕ tɕʰ ɕ/ are in complementary distribution (see minimal pair) with the alveolar consonants /ts tsʰ s/, retroflex consonants /tʂ tʂʰ ʂ/ and velar consonants /k kʰ x/. As a result, linguists prefer to classify /tɕ tɕʰ ɕ/ as allophones of one of the three other sets. The Yale and Wade-Giles systems, for example, mostly treat the palatals as allophones of the retroflex consonants; Tongyong Pinyin mostly treats them as allophones of the dentals; and Chinese Braille treats them as allophones of the velars.

/tɕ tɕʰ ɕ/ may be pronounced as [tsj tsʰj sj], which is characteristic of the speech of young women, and also of some men. This is usually considered rather effeminate and may also be considered substandard.

The null initial is most commonly realized as [ɰ], though [n], [ŋ], [ɣ], and [ʔ] are common in other dialects of Mandarin.

Finals

The final, or rime, of a syllable, in Standard Mandarin, is the part after the initial consonant. A Mandarin final can be structurally described as (Vm)V(Cf). In other words, it consists of an optional medial, a nucleus, and an optional coda. When present, the medial can be one of the three glides corresponding to the three high vowels: /i/, /u/, /y/. The coda can be absent; it can be one of two glides: -i and -u; or it can be one of two nasals: -n, -ŋ.

Not counting tone distinctions, there are about 35 distinct finals in Mandarin.

There are at least the following phones:

- [a] (only in finals [a], [ia], [ua], [ya], [aɪ], [uaɪ], [uan])

- [ɑ] (only in finals [ɑʊ], [iɑʊ], [ɑŋ], [iɑŋ], [uɑŋ])

- [e] (only in finals [eɪ] and [ueɪ])

- [ɛ] (only in finals [iɛ], [iɛn], [yɛn] and in the isolated word [ɛ])

- [œ] (only in final [yœ])

- [o] (only in finals [ou] and [iou])

- [ɔ] (only in final [uɔ] and in the isolated word [ɔ])

- [ə] (only in finals [ən], [uən], [əŋ], [uəŋ])

- [ɤ] (only in final [ɤ])

- [z̩] (only in final [z̩], which occurs only after alveolar sibilants; sometimes pronounced as [ɨ])

- [ʐ̩] (only in final [ʐ̩̩], which occurs only after retroflex sibilants; sometimes pronounced as [ɨ])

- [i] (only in finals [i], [in], [iŋ])

- [ʊ] (only in finals [ʊŋ], [yʊŋ])

- [u] (only in final [u])

- [y] (only in final [y], [yn])

This shows fourteen different vowels. By very conservative standards, this represents a system of eight phonemes: /a/ ([a]/[ɑ]), /e/ ([e]/[ɛ]), /o/ ([o]/[ɔ]), /ə/ ([ə]/[ɤ]), /z̩/([z̩]/[ʐ̩]), /i/, /u/ ([ʊ]/[u]), and /y/.

Further reduction can be achieved by noticing that /e/, /o/, and /ə/ are in complementary distribution, and can be treated as a single phoneme /ə/ (except in the isolated words [ɛ] and [ɔ], which function only as exclamations and can be treated as outside of the core system (similar to the normal treatment of "hmm", "unh-unh", "shhh!" and other English exclamations that violate usual syllabic constraints). Note also that the finals [iɛn] can be considered to be phonemically either /iən/ or /ian/; likewise for [yɛn], which can be either /yən/ or /yan/. (Taking into account that [iɛn] and [yɛn] become [iaɻ] and [yaɻ] upon rhotacization, the former interpretation seems more likely.) It would also be possible to merge /z̩/ and /i/, provided that the palatal and retroflex series are not themselves merged, since /i/ does not occur after retroflex or velar sounds or after dental fricatives and affricates. If all of these suggestions are followed, and [iɛn] and [yɛn] considered to be /ian/ and /uan/, the resulting system of /a/, /ə/, /i/, /u/, and /y/ is much like the standard Pinyin romanization scheme (except that Pinyin does not merge /ə/ with /o/ and uses a certain number of shortcut spellings).

An even more reduced system results from considering main vowel /i/, /u/ and /y/ to be the surface results of the respective glides combined with a null meta-phoneme. This system, shown below, analyzes the final part of a syllable as a combination of a glide slot (/i/, /u/, /y/ or null), a main vowel slot (/a/, /ə/ or null), and a coda slot (/i/, /u/, /n/, /ŋ/ or null). (The minimal vowel /z̩/ ([z̩]/[ʐ̩] or [ɨ]) is considered to be the surface manifestation when all three slots are null, rather than an allophone of main vowel /i/.)

When the medial, nucleus, and coda combine into a final, their pronunciations may be affected. The following is the full table of finals of Standard Mandarin in IPA:

| Nucleus | Coda | Medial | |||

| Ø | i | u | y | ||

| a | Ø | a | ia | ua | |

| i | aɪ | uaɪ | |||

| u | ɑʊ | iɑʊ | |||

| n | an | iɛn | uan | yɛn | |

| ŋ | ɑŋ | iɑŋ | uɑŋ | ||

| ə | Ø | ɤ | iɛ | uo 1 | yɛ ² |

| i | ei | uei | |||

| u | ɤʊ | iɤʊ | |||

| n | ən | in | uən | yn | |

| ŋ | ɤŋ | iŋ | uɤŋ ³ | yʊŋ | |

| Ø | z̩ | i | u | y | |

1 Both pinyin and zhuyin have an additional "o", used after "b p m f", which is distinguished from "uo", used after everything else. "o" is generally put into the first column instead of the third. However, in Beijing pronunciation, these are identical.

² Another way to represent the four finals of this line is: [ɯʌ iɛ uɔ yœ], which reflects Beijing pronunciation.

³ /uɤŋ/ is pronounced [ʊŋ] when it follows an initial.

Corresponding chart in:

- Pinyin

- Zhuyin

- Gwoyeu Romatzyh

A table of valid initial and final combinations can also be seen at:

R Finals

Standard Mandarin also uses a rhotic consonant, /ɚ/. This usage is a unique feature of Standard Mandarin, other dialects lack this sound. In Chinese, this feature is known as Erhua. There are two cases in which it is used:

- In a small number of words, such as 二 "two", 耳 "ear", etc. All of these words are pronounced as [ɑɚ] with no initial consonant.

- As a noun suffix (Traditional: -兒, Simplified: -儿). The suffix combines with the final, and regular but complex changes occur as a result.

The "r" final must be distinguished from the retroflex semi-vowel written as "ri" in the pinyin spelling and represented either by [ʐ] or [ɹ] in IPA. Saying "The star rode a donkey," in English, or "Wo nü-er ru yiyuan" (My daughter entered the hospital), will make it clear that the first "r" in either case is said with a relatively lax tongue, whereas the second "r" sounds both involve a very active curling of the tongue and contact with the top of the mouth.

In other dialects of Mandarin, the rhotic consonant is sometimes replaced by another syllable, such as "li" in words that indicate locations. For example, "zher" and "nar" become "zhe li" and "na li," respectively.

Tones

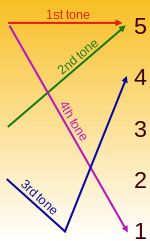

Mandarin, like all Chinese dialects, is a tonal language. This means that tones, just like consonants and vowels, are used to distinguish words from each other. Many foreigners have difficulties mastering the tones of each character, but correct tonal pronunciation is essential for intelligibility because of the vast number of characters in the language that only differ by tone (i.e. are minimal pairs with respect to tone). The following are the 4 tones of Standard Mandarin:

| Tone name | Yin Ping | Yang Ping | Shang | Qu |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tone contour | 55 | 35 | 21 (4) | 51 |

| Tone number | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

- First tone, or high-level tone (陰平/阴平 yīnpíng, literal meaning: yin-level):

- a steady high sound, as if it were being sung instead of spoken.

- Second tone, or rising tone (陽平/阳平 yángpíng, literal meaning: yang-level), or linguistically, high-rising:

- is a sound that rises from mid-level tone to high (e.g., What?!)

- Third tone (low tone, or low-falling-raising, 上聲/上声 shǎngshēng or shàngshēng, literal meaning: "up tone"):

- has a mid-low to low descent; if at the end of a sentence or before a pause, it is then followed by a rising pitch.

- Fourth tone, falling tone (去聲/去声 qùshēng, literal meaning: "away tone"), or high-falling:

- features a sharp downward accent ("dipping") from high to low, and is a shorter tone, similar to curt commands. (e.g., Stop!)

Neutral tone

Also called Fifth tone or zeroth tone (in Chinese: 輕聲/轻声 qīng shēng, literal meaning: "light tone"), neutral tone is sometimes thought of incorrectly as a lack of tone. It is fairly rare and usually comes at the end of a word or phrase, and is pronounced in a light and short manner. The neutral tone is particularly difficult for non-native speakers to master correctly because of its uncharacteristically large number of allotone contours: the level of its pitch depends almost entirely on the tone carried by the syllable preceding it. The situation is further complicated by the amount of dialectal variation associated with it; in some regions, notably Taiwan, neutral tone is relatively uncommon.

Despite many examples of minimal pairs (for example, 要是 and 钥匙, yàoshì if and yàoshi key, respectively) it is sometimes described as something other than a full-fledged tone for technical reasons: namely because some linguists have historically felt that the tonality of a syllable carrying the neutral tone results from a "spreading out" of the tone on the syllable before it. This idea is appealing intuitively because without it, the neutral tone requires relatively complex tone sandhi rules to be made sense of; indeed, it would have to have 4 separate allotones, one for each of the four tones that could precede it. Despite this, however, it has been shown that the "spreading" theory inadequately characterizes the neutral tone, especially in sequences where more than one neutrally toned syllable are found adjacent[1].

The following are from Beijing dialect[2]. Other dialects may be slightly different.

| Tone of first syllable | Pitch of neutral tone | Example | Pinyin | English meaning |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 玻璃 | bōli | glass |

| 2 | 3 | 伯伯 | bóbo | uncle |

| 3 | 4 | 喇叭 | lăba | horn |

| 4 | 1 | 兔子 | tùzi | rabbit |

Most romanizations represent the tones as diacritics on the vowels (e.g., Pinyin, MPS II and Tongyong Pinyin). Zhuyin uses diacritics as well. Others, like Wade-Giles, use superscript numbers at the end of each syllable. The tone marks and numbers are rarely used outside of language textbooks. Gwoyeu Romatzyh is a rare example where tones are not represented as special symbols, but using normal letters of the alphabet (although in a very complex fashion).

To listen to the tones, see http://www.wku.edu/~shizhen.gao/Chinese101/pinyin/tones.htm (click on the blue-red yin yang symbol).

Tone sandhi

Pronunciation also varies with context according to the rules of tone sandhi. The most prominent phenomenon of this kind is when there are two third tones in immediate sequence, in which case the first of them changes to a rising tone. This tone contour is sometimes described incorrectly as being equivalent to second tone; while the two are very similar, many native speakers can distinguish them (compare 起码 and 骑马, pinyin qĭ mă and qí mă respectively). In the literature, this contour is often called two-thirds tone or half-third tone. If there are three third tones in series, the tone sandhi rules become more complex, and depend on word boundaries, stress, and dialectal variations.

Relationship between Middle Chinese and modern tones

Relationship between Middle Chinese and modern tones:

V- = unvoiced initial consonant

L = sonorant initial consonant

V+ = voiced initial consonant (not sonorant)

| Middle Chinese Tone | Ping (平) | Shang (上) | Qu (去) | Ru (入) | ||||||||

| Middle Chinese Initial | V- | L | V+ | V- | L | V+ | V- | L | V+ | V- | L | V+ |

| Standard Mandarin Tone name | Yin Ping (陰平, 1) | Yang Ping (陽平, 2) | Shang (上, 3) | Qu (去, 4) | redistributed with no pattern | to Qu | to Yang Ping | |||||

| Standard Mandarin Tone contour | 55 | 35 | 214 | 51 | to 51 | to 35 | ||||||

It is known that if the two morphemes of a compound word cannot be ordered by grammar, the order of the two is usually determined by tones — Yin Ping (1), Yang Ping (2), Shang (3), Qu (4), and Ru, which is the plosive-ending tone that has already disappeared. Below are some compound words that show this rule. Tones are shown in parentheses, and R indicates Ru.

左右 (34)

南北 (2R)

輕重 (14)

貧富 (24)

凹凸 (1R)

喜怒 (34)

哀樂 (1R)

生死 (13)

死活 (3R)

陰陽 (12)

明暗 (24)

毀譽 (34)

褒貶 (13)

離合 (2R)

Standard Mandarin and Beijing dialect

By the official definition of the People's Republic of China, Standard Mandarin uses:

- The phonology or sound system of Beijing. A distinction should be made between the sound system of a dialect or language and the actual pronunciation of words in it. The pronunciations of words chosen for Standard Mandarin -- a standardized speech -- do not necessarily reproduce all of those of the Beijing dialect. The pronunciation of words is a standardization choice and occasional standardization differences (not accents) do exist, between putonghua and guoyu, for example.

In fluent speech, Chinese speakers can easily tell the difference between a speaker of the Beijing dialect and a speaker of Standard Mandarin. Beijingers speak Standard Mandarin with elements of their own dialect in the same way as other speakers.

- The vocabulary of Mandarin dialects in general. This means that all slang and other elements deemed "regionalisms" are excluded. On the one hand, the vocabulary of all Chinese dialects, especially in more technical fields like science, law, and government, are very similar. (This is similar to the profusion of Latin and Greek words in European languages.) This means that much of the vocabulary of standardized Mandarin is shared with all varieties of Chinese. On the other hand, many colloquial vocabulary and slang found in Beijing dialect are not found in Standard Mandarin, and may not be understood by people outside Beijing.

- The grammar and usage of exemplary modern Chinese literature, such as the work of Lu Xun, collectively known as "Vernacular Chinese" (baihua). Vernacular Chinese, the standard written form of modern Chinese, is in turn based loosely upon a mixture of northern (predominant), southern, and classical grammar and usage. This gives formal standard Mandarin structure a slightly different feel from that of street Beijing dialect.

In theory the Republic of China in Taiwan defines standard Mandarin differently, though in reality the differences are minor and are concentrated mostly in the tones of a small minority of words.

Speakers of Standard Mandarin generally have little difficulty understanding the Beijing accent, which the former is based on. Natives of Beijing commonly add a final "er" (/ɻ/) (兒音/儿音; pinyin: éryīn) — commonly used as a diminutive — to vocabulary items, as well as use more neutral tones in their speech. An example of Standard Mandarin versus the Beijing dialect would be: standard men (door) compared with Beijing menr. These give the Beijing dialect a somewhat distinctive lilt compared to Standard Mandarin spoken elsewhere. The dialect is also known for its rich colloquialisms and idiomatic expressions.

Although Chinese speakers make a clear distinction between Standard Mandarin and the Beijing dialect, there are aspects of Beijing dialect that have made it into the official standard. Standard Mandarin has a T-V distinction between the polite and informal versions of you that comes from Beijing dialect. In addition, there is a distinction between "zánmen" (we including the listener) and "wǒmen" (we not including the listener). In practice, neither distinction is commonly used by most Chinese.

The following samples are some Beijing dialects which are not yet accepted into Standard Mmandarin:

倍儿: bei er means 'very much'; 拌蒜: ban suan means 'stagger'; 不吝: bu lin means 'do not worry about'; 撮: cuo means 'eat'; 出溜: chu liu means 'slip'; 大老爷儿们儿: da lao ye men means 'man, male';

The following samples are some Beijing dialects which have been already accepted as Standard Mandarin in recent years. 二把刀: er ba dao means 'not very skillful'; 哥们儿: ge men er means 'good male friends', "buddies"; 抠门儿: kou men means 'parsimony'.

Standard Mandarin and other dialects and languages

Although Standard Mandarin is now firmly estabished as the lingua franca in Mainland China, the national standard can be somewhat different from the other local dialects in the vast Mandarin dialect group, to the point of being to some extent unintelligible. Pronunciation differences though within the Mandarin group are usually regular, usually differing only in the tones. For example, the character for "sky" 天 is pronounced with the first tone in the Beijing dialect and in Standard Mandarin (pinyin: tian), but is the fourth tone in Tianjin dialect. In dialects outside the Mandarin group it can range from ti (with light tone in Shanghainese dialect) to teen in the high level or high falling tone in Standard Cantonese.

Although both Mainland China and Taiwan use Standard Mandarin in the official context and are keen to promote its use as a national lingua franca, there is no official intent to have Standard Mandarin replace the regional languages. As a practical matter of fact, speaking only Standard Mandarin in areas such as in southern China or Taiwan could be a significant social handicap; some elderly or rural Chinese-language speakers there do not speak Standard Mandarin fluently (although most do understand it). In addition, it is also very common for it to be spoken with the the speaker's regional accent, depending on factors as age, level of education, and the need and frequency to speak correctly for official or formal purposes. This situation appears to be changing, though, in large urban centers, as social changes, migrations, and urbanization take place.

In the predominantly Han areas in Mainland China, while the use of Standard Mandarin is encouraged as the common working language, the PRC has been sensitive to the status of local dialects and has not discouraged their use. Standard Mandarin is very commonly used for logistical reasons as in many parts of southern China, the linguistic diversity is so large that neighboring city dwelllers may have difficulties communicating with each other without a common lingua franca.

In Taiwan, the relationship between Standard Mandarin and local dialects, particularly Taiwanese, has been more heated. Following the Kuomintang (KMT) rule from 1949 until the lifting of martial law in the 1980s, the KMT government has discouraged or even forbidden the use of Taiwanese and other local vernaculars. This produced a backlash in the 1990s, amongst more extreme supporters of Taiwan independence. Under the current Chen Shui-Bian administration, the Taiwanese languages are being taught as an individual class, with dedicated textbooks and course materials. The current President, Chen Shui-Bian, often breaks into Taiwanese during speeches, while the former President, Lee Teng-hui, , also speaks Taiwanese openly when interviewed in the media.

In Singapore, the government has heavily promoted a "Speak Mandarin Campaign" since the late 1960s. The use of non-Mandarin dialects in broadcast media is prohibited and the use of dialect in any context is officially discouraged. This has led to some resentment amongst the older generations, as Singapore's migrant Chinese community is made up almost entirely of south Chinese descent. Lee Kuan Yew, the initiator of the campaign, admitted that to most Chinese Singaporeans, Mandarin was a "stepmother tongue" rather than a true mother language. Nevertheless, he saw the need for a unified language among the Chinese community not biased in favor of any dialect group.[3]

See also:

Accents

Most Chinese (Beijingers included) speak Standard Mandarin with elements of their own dialects (i.e. their "accents") mixed in.

For example, natives of Beijing, add a final "er" (/ɻ/) — commonly used as a diminutive — sound to vocabulary items that other speakers would leave unadorned (兒音/儿音; pinyin: éryīn).

On the other hand, speakers from northeastern and southern China as well as Taiwan often mix up zh and z, ch and c, sh and s, h and f, and l and n because their own home dialects often do not make these distinctions. As a result, it can be difficult for people who do not have the standard pronunciation to use pinyin, because they do not distinguish these sounds.

See List of Chinese dialects for a list of articles on individual Chinese dialects and how their features differ from Standard Mandarin.

Role of standard Mandarin

From an official point of view, Standard Mandarin is theoretically something like a lingua franca — a way for speakers of the many mutually unintelligible Han Chinese dialects/languages, as well as the Han and non-Han ethnic groups to communicate with each other. The very name Putonghua, or "common speech", reinforces this idea. In practice, however, due to Standard Mandarin being a "public" lingua franca, other languages or dialects, both Han and non-Han, have shown signs of losing ground to Standard Mandarin, to the chagrin of certain local culture proponents.

In December 2004, the first survey of language use in the People's Republic of China revealed that only 53% of its population, about 700 million people, could communicate in Standard Mandarin. (China Daily) A survey by South China Morning Post released in September 2006 gave the same result.[citation needed] This 53% is defined as a passing gradd above 3-B (ie. error rate lower than 40%) of Evaluation Exam. Another survey in 2003 by China National Language And Character Working Committee shows, if mastery of Standard Mandarin is defined as Grade 1-A (ie. error rate lower than 3%), the percentages as follows are: Beijing 90%, Shanghai 3%, Tianjin 25%, Guangzhou 0.5%, Dalian 10%, Xi`an 12%, Chengdu 1%, Nanjing 2%.[citation needed] Consequently, foreign learners of Mandarin usually opt to learn at Beijing, although grammar and character learning is not confined to that area.

With the high-speed development of China, more Chinese people leaving rural areas for cities for job or study opportunities, and the Mandarin Level Evaluation Exam has quickly become very popular. Most university graduates usually take this Exam before looking for a job. Many companies require a basic Mandarin Level Evaluation Certificate from their applicants, barring applicants who were born or bred in Beijing, since their Proficiency level is believed to be inherently 1-A (一级甲等)(Error rate: lower than 3%). As for the rest, the score of 1-A is rare.[citation needed] People who get 1-B (Error rate: lower than 8%) are considered qualified to work as television correspondents or in broadcasting stations. 2-A (Error rate: lower than 13%) can work as Chinese Literature Course teachers in public schools. Other levels include: 2-B (Error rate: lower than 20%), 3-A (Error rate: lower than 30%) and 3-B (Error rate: lower than 40%). In China, a proficiency of level 3-B usually cannot be achieved unless special training is received. Even if most Chinese do not speak Standard Mandarin with standard pronunciation, spoken Standard Mandarin is understood by virtually almost everyone.

The China National Language And Character Working Committee was founded in 1985. One of its important responsibilities is to promote Standard Mandarin and Mandarin Level proficiency for Chinese native speakers. (Its website link can be found on external links.)

See also

- Mandarin (linguistics)

- Naples Eastern University

- Beijing dialect

- Chinese grammar

- Mandarin slang

- Chinese speech synthesis

Notes

- ^ Yiya Chen and Yi Xu, Pitch Target of Mandarin Neutral Tone (abstract), presented at the 8th Conference on Laboratory Phonology

- ^ Wang Jialing, The Neutral Tone in Trysyllabic Sequences in Chinese Dialects, Tianjin Normal University, 2004

- ^ Lee Kuan Yew (2000). From Third World to First: The Singapore Story: 1965-2000. HarperCollins. ISBN 0-06-019776-5.

References

- Chao, Y.R., A Grammar of Spoken Chinese, University of California Press, (Berkeley), 1968.

- Hsia, T., China’s Language Reforms, Far Eastern Publications, Yale University, (New Haven), 1956.

- Ladefoged, Peter; & Maddieson, Ian. (1996). The sounds of the world's languages. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers. ISBN 0-631-19814-8 (hbk); ISBN 0-631-19815-6 (pbk).

- Ladefoged, Peter; & Wu, Zhongji. (1984). Places of articulation: An investigation of Pekingese fricatives and affricates. Journal of Phonetics, 12, 267-278.

- Lehmann, W.P. (ed.), Language & Linguistics in the People’s Republic of China, University of Texas Press, (Austin), 1975.

- Lin, Y., Lin Yutang's Chinese-English Dictionary of Modern Usage, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, 1972.

- Milsky, C., "New Developments in Language Reform", The China Quarterly, No.53, (January-March 1973), pp.98-133.

- Norman, J., Chinese, Cambridge University Press, (Cambridge), 1988.

- Ramsey, R.S.(1987). The Languages of China. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-01468-X

- San Duanmu (2000) The Phonology of Standard Chinese ISBN 0-19-824120-8

- Seybolt, P.J. & Chiang, G.K. (eds.), Language Reform in China: Documents and Commentary, M.E. Sharpe, (White Plains), 1979.

- Simon, W., A Beginners' Chinese-English Dictionary Of The National Language (Gwoyeu): Fourth Revised Edition, Lund Humphries, (London), 1975.

- Stalin, J.V., "Concerning Marxism in Linguistics", Pravda, Moscow, (20 June, 1950), simultaneously published in Chinese in Renmin Ribao, English translation: Stalin, J.V., Marxism and Problems of Linguistics, Foreign Languages Press, (Peking), 1972.

External links

- General Introduction of Chinese Language

- The World of Chinese Chinese Learning Magazine

- Mandarin Learning

- Standard MandarinNational Language And Character Working Committee - Mandarin Level Evaluation Exam

- The World of Chinese Literature Mandarin Learning Magazine

- http://chinese.hm68.com - Free Online Chinese Class