Hummingbird

This article may require copy editing for grammar, style, cohesion, tone, or spelling. (January 2008) |

| Hummingbird | |

|---|---|

| |

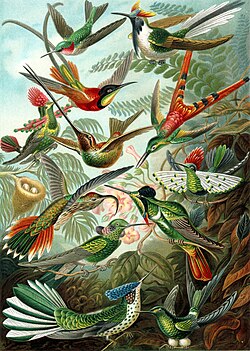

| A variety of hummingbirds from Ernst Haeckel's 1904 Kunstformen der Natur (Artforms of Nature) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Subclass: | |

| Infraclass: | |

| Superorder: | |

| (unranked): | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | Trochilidae Vigors, 1825

|

| Subfamilies | |

|

For a taxonomic list of genera, see: For an alphabetic species list, see: | |

Hummingbirds are small birds of the family Trochilidae, and are native only to the Americas. They are known for their ability to hover in mid-air by rapidly flapping their wings 15–80 times per second (depending on the species). Capable of sustained hovering, the hummingbird also has the ability to fly backwards, being the only group of birds able to do so[1]. Hummingbirds may also fly vertically or horizontally, and are capable of maintaining a position while drinking nectar or eating tiny arthropods from flower blossoms. Their English name derives from the characteristic hum made by their wings.

Appearance

Hummingbirds are small birds with long, thin bills. The elongated bill is one of the defining characteristics of the hummingbird. The bill combined with an extendable, bifurcated tongue, has evolved in order to allow the bird to feed upon nectar deep within flowers. A hummingbird's lower bill (mandible) also has the ability to flex downward to create a wider opening, facilitating the capture of insects in the mouth rather than at the tip of the beak.[2]

The Bee Hummingbird (Mellisuga helenae) is the smallest bird in the world, weighing 1.8 grams (0.06 ounces) and measuring about 5 cm (2 inches). A typical North American hummingbird, such as the Rufous Hummingbird (Selasphorus rufus), weighs approximately 3 g (0.106 ounces) and has a length of 10–12 cm (3.5–4 inches). The largest hummingbird is the Giant Hummingbird (Patagona gigas), with some individuals weighing as much as 24 grams (0.85 ounces) and measuring 21.5 cm (8.5 inches).

Most species exhibit conspicuous sexual dimorphism, with males more brightly colored and females displaying more cryptic coloration. [3] Iridescent plumage is present in both sexes of most species, with green being the most common color. Highly modified structures within certain feathers, usually concentrated on the head and breast, produce intense metallic iridescence in a rainbow of colors.

Feeding

Hummingbirds are attracted to many flowering plants — Pachystachys lutea, bee balm, Heliconia, Buddleia, Hibiscus, bromeliads, cannas, verbenas, honeysuckles, salvias, pentas, fuchsias, many penstemons, and others. Once attracted to a garden, hummingbirds may find flowers of other colors more attractive. The location and growing season should determine choices of the plants selected for a garden to attract hummingbirds. They feed on the nectar of these plants and are important pollinators, especially of deep-throated flowers. Nectar is a poor source of nutrients, so hummingbirds meet their needs for protein, amino acids, vitamins, minerals, etc. by preying on insects and spiders, especially when feeding young. Like bees, hummingbirds assess the amount of sugar in the nectar they eat; they reject flower types that produce nectar which is less than 12% sugar and prefer those whose sugar content is around 25%.

Unlike most other birds, hummingbird bills have a pronounced overlap, with the upper bill curving around and over the sides of the smaller lower bill. When hummingbirds feed, the bill is usually only opened slightly, allowing the bill-shaped tongue to dart out and into the interior of flowers. The bill is rarely opened wide and in any case is limited in how far it can be opened, but is used for variety of tasks, including catching insects in flight, preening feathers, carrying nesting material, constructing nests, feeding baby hummingbirds and attacking rivals. Most hummingbirds have straight bills of various lengths, although many have downwardly curved bills. Though the curves are gentle in most cases, they are extreme in a few cases such as Sicklebills, whose bills are extremely down-curved to help them access their particular choice of flowers.

Hummingbirds do not spend all day flying, as the energy costs of this would be prohibitive. In fact, they spend most of their lives sitting, perching and watching the world. Hummingbirds feed in many small meals, consuming up to their own body weight in nectar and insects per day. They spend an average 10%-15% of their time feeding and 75%-80% sitting, digesting and watching. Obtaining this much food requires a lot of work. Scientists have recorded a Costa's Hummingbirds making 42 feeding flights in 6-5 hours, during which time it visited 1,311 flowers.

Co-evolution with ornithophilous flowers

Hummingbirds are specialized nectarivores (Stiles, 1981) and are tied to the ornithophilous flowers they feed upon. Some species, especially those with unusual bill shapes such as the Sword-billed Hummingbird and the sicklebills, are coevolved with a small number of flower species. Many plants pollinated by hummingbirds produce flowers in shades of red, orange, and bright pink, though the birds will take nectar from flowers of many colors. Hummingbirds can see wavelengths into the near-ultraviolet, but their flowers do not reflect these wavelengths as many insect-pollinated flowers do. This narrow color spectrum may render hummingbird-pollinated flowers relatively inconspicuous to most insects, thereby reducing nectar robbing. [4] [5] Hummingbird-pollinated flowers also produce relatively weak nectar (averaging 25% sugars w/w) containing high concentrations of sucrose, whereas insect-pollinated flowers typically produce more concentrated nectars dominated by fructose and glucose.[6]

Aerodynamics of flight

Hummingbirds fly particularly well in wind tunnels. For this reason, hummingbird flight has been studied intensively from an aerodynamic perspective with high-speed video cameras.

Writing in Nature, the biomechanist Douglas Warrick and coworkers studied the Rufous Hummingbird, Selasphorus rufus, in a wind tunnel using particle image velocimetry techniques and investigated the lift generated on the bird's upstroke and downstroke.

They concluded that their subjects produced 75% of their weight support during the down-stroke and 25% during the up-stroke: many earlier studies had assumed (implicitly or explicitly) that lift was generated equally during the two phases of the wingbeat cycle, as is the case of insects of a similar size. This finding shows that hummingbirds' hovering is similar to, but distinct from, that of hovering insects such as the hawk moths. [8]

The Giant Hummingbird's wings beat at 8–10 beats per second, the wings of medium-sized hummingbirds beat about 20–25 beats per second and the smallest beat 70 beats per second.

Metabolism

With the exception of insects, hummingbirds while in flight have the highest metabolism of all animals, a necessity in order to support the rapid beating of their wings. Their heart rate can reach as high as 1,260 beats per minute, a rate once measured in a Blue-throated Hummingbird [1]. They also typically consume more than their own weight in nectar each day, and to do so they must visit hundreds of flowers daily. At any given moment, they are only hours away from starving.

However, they are capable of slowing down their metabolism at night, or any other time food is not readily available. They enter a hibernation-like state known as torpor. During torpor, the heart rate and rate of breathing are both slowed dramatically (the heart rate to roughly 50–180 beats per minute), reducing their need for food. Most organisms with very rapid metabolism have short lifespans; however hummingbirds have been known to survive in captivity for as long as 17 years.

Studies of hummingbirds' metabolism are highly relevant to the question of whether a migrating Ruby-throated Hummingbird can cross 800 km (500 miles) of the Gulf of Mexico on a nonstop flight, as field observations suggest it does. This hummingbird, like other birds preparing to migrate, stores up fat to serve as fuel, thereby augmenting its weight by as much as 40–50 percent and hence increasing the bird's potential flying time.[9]

Range

Hummingbirds are found only in the Americas, from southern Alaska and Canada to Tierra del Fuego, including the Caribbean. The majority of species occur in tropical Central and South America, but several species also breed in temperate areas. Only the migratory Ruby-throated Hummingbird breeds in continental North America east of the Mississippi River and Great Lakes. The Black-chinned Hummingbird, its close relative and another migrant, is the most widespread and common species in the western United States, while the Rufous Hummingbird is the most widespread species in western Canada. [10]

Most hummingbirds of the U.S. and Canada migrate south in fall to spend the northern winter in Mexico or Central America. A few southern South American species also move to the tropics in the southern winter. A few species are year-round residents in the warmer coastal and interior desert regions. Among these is Anna's Hummingbird, a common resident from southern California inland to southern Arizona and north to southwestern British Columbia.

The Rufous Hummingbird is one of several species that breed in western North America and are wintering in increasing numbers in the southeastern United States, rather than in tropical Mexico. Thanks in part to artificial feeders and winter-blooming gardens, hummingbirds formerly considered doomed by faulty navigational instincts are surviving northern winters and even returning to the same gardens year after year. Individuals that survive winters in the north may have altered internal navigation instincts that could be passed on to their offspring. The Rufous Hummingbird nests farther north than any other species and must tolerate temperatures below freezing on its breeding grounds. This cold hardiness enables it to survive temperatures down to at least -4 °C (25 °F), provided that adequate shelter and feeders are available.

Reproduction

As far as is known, male hummingbirds do not take part in nesting. Most species make a cup-shaped nest on the branch of a tree or shrub. Two white eggs are laid, which despite being the smallest of all bird eggs, are in fact large relative to the hummingbird's adult size. Incubation is typically 12–19 days. The nest varies in size relative to species, from smaller than half of a walnut shell to several centimeters in diameter.

Systematics and evolution

Traditionally, hummingbirds are placed in the order Apodiformes, which also contains the swifts, though some taxonomists have separated them into their own order, Trochiliformes. Hummingbirds' wings are hollow and fragile, making fossilization difficult and leaving their evolutionary history a mystery. Some scientists also believe that the hummingbird evolved relatively recently. Scientists also theorize that hummingbirds originated in South America, where there is the greatest species diversity. Brazil, Peru and Ecuador contain over half of the known species.

There are between 325 and 340 species of hummingbird, depending on taxonomic viewpoint, historically divided into two subfamilies, the hermits (subfamily Phaethornithinae, 34 species in six genera), and the typical hummingbirds (subfamily Trochilinae, all the others). However, recent phylogenetic analyses by Mcguire et al. (2007) suggest that this division is slightly inaccurate, and that there are nine major clades of hummingbirds: the Topazes, the hermits, the Mangoes,the coquettes, the Brilliants, the Giant Hummingbird (Patagonia gigas), the Mountain Gems, the Bees, and the Emeralds. The Topazes (Topaza pella and Florisuga mellivora) have the oldest split with the rest of the hummingbirds.

Genetic analysis[citation needed] has indicated that the hummingbird lineage diverged from their closest relatives some 35 million years ago, in the Late Eocene, but fossil evidence is limited. Fossil hummingbirds are known from the Pleistocene of Brazil and the Bahamas—though neither has yet been scientifically described—and there are fossils and subfossils of a few extant species known, but until recently, older fossils had not been securely identifiable as hummingbirds.

The modern diversity of hummingbirds is thought by evolutionary biologists to have evolved in South America, as the great majority of the species are found there. However, the ancestor of extant hummingbirds may have lived in parts of Europe to what is southern Russia today.

In 2004, Dr. Gerald Mayr of the Senckenberg Museum in Frankfurt am Main identified two 30-million-year-old hummingbird fossils and published his results in Nature.[11] The fossils of this primitive hummingbird species, named Eurotrochilus inexpectatus ("unexpected European hummingbird"), had been sitting in a museum drawer in Stuttgart; they had been unearthed in a clay pit at Wiesloch-Frauenweiler, south of Heidelberg, Germany and, because it was assumed that hummingbirds never occurred outside the Americas, were not recognized to be hummingbirds until Mayr took a closer look at them.

Fossils of birds not clearly assignable to either hummingbirds or a related, extinct family, the Jungornithidae, have been found at the Messel pit and in the Caucasus, dating from 40–35 mya, indicating that the split between these two lineages indeed occurred at that date. The areas where these early fossils have been found had a climate quite similar to the northern Caribbean or southernmost China during that time. The biggest remaining mystery at the present time is what happened to hummingbirds in the roughly 25 million years between the primitive Eurotrochilus and the modern fossils. The astounding morphological adaptations, the decrease in size, and the dispersal to the Americas and extinction in Eurasia all occurred during this timespan. DNA-DNA hybridization results [12] suggest that the main radiation of South American hummingbirds at least partly took place in the Miocene, some 12–13 mya, during the uplifting of the northern Andes.

Lists of species and genera

Hummingbirds and humans

Their relatively small size, brilliant colors, fearless personalities, and remarkable mode of flight have won hummingbirds nearly universally admiration from humans. They do not harm crops or livestock, make loud noises, foul cars or buildings with their droppings, or bite when handled, making them among the most benign of all birds.

Hummingbirds have not always benefited from this admiration. Their beauty and novelty made them popular with commercial and scientific collectors in the 19th century; many fashionable parlors were decorated with glass cases containing preserved specimens of hummingbirds and other colorful tropical species. Their demanding dietary requirements and high metabolism kept them from becoming popular as pets, though many have been imported into Europe and the United States for zoos and private aviaries.

Habitat destruction and climate change are the most pervasive threats to all hummingbirds, but other human-related causes of hummingbird mortality include pesticide poisoning; collisions with windows, cars, utility lines, and transmission towers; predation by domestic cats; electrocution on electric fences; and entanglement in the hooked spines of burdock, an alien weed.

Hummingbirds sometimes fly into buildings, especially garages, possibly while investigating brightly colored objects such as flower arrangements, floral draperies, and emergency release handles for automatic garage doors. Once inside, they may be unable to escape because their natural instinct when threatened or trapped is to fly upward. This is a life-threatening situation for hummingbirds, as they can become exhausted and die in a relatively short period of time, possibly as little as an hour. It is usually difficult to catch a trapped hummingbird until it is exhausted, and handling such small birds requires extreme delicacy of touch. Sometimes a trapped hummingbird will land on a broom or a long branch if it is moved very carefully into a position near the bird. Once relaxed on the perch, the bird may remain long enough to allow itself to be carried outside to safety. A more time-consuming but less traumatic alternative is to place a feeder near where the trapped bird is flying or perching, waiting until it begins using the feeder, then moving the feeder a few feet at a time toward an open door or window. Once the feeder is hanging in the opening, the bird should notice the escape route on its own.

Feeders and artificial nectar

The diet of hummingbirds requires an energy source (typically nectar) and a protein source (typically small insects). Providing many plants that carry blooms used by hummingbirds is the safest way to provide nectar for hummingbirds. Through careful plant selection, gardens may contain plants that bloom at different times to attract hummingbirds throughout the seasons they are present in an area. Placing these plants near windows affords a good view of the birds. Hummingbirds will also take synthetic nectar from artificial feeders. Such feeders allow people to observe and enjoy hummingbirds up-close while providing the hummingbirds with a reliable supply of nectar, especially when flower blossoms are less abundant. Maintaining cleanliness of the feeder is essential for the health of the birds. Homemade nectar can be made by adding 1 part white, granulated table sugar to 3 to 5 parts water. Brief boiling will dissolve the sugar more quickly and may slow spoilage of the solution. Once cooled, the nectar is ready to pour into a clean feeder.

Things to avoid using in feeders include honey, which should not be used because it promotes the growth of microorganisms that may be dangerous to hummingbirds.[13] Artificial sweeteners should also be avoided because, although the hummingbirds will drink it, they will be starved of the calories they need to sustain their metabolism. Some commercial hummingbird foods contain red dyes and preservatives, which are unnecessary and possibly dangerous to the birds, so dyes and preservatives should be avoided because neither have been studied for long-term effects on hummingbirds. While it is true that bright colors, especially red, initially attract hummingbirds more quickly than others, it is better to use a feeder that has some red on it, rather than coloring the liquid offered in it. It is possible that red dye is harmful to hummingbirds.[14] Commercial nectar mixes may contain small amounts of mineral nutrients which are useful to hummingbirds, but hummingbirds get all the nutrients they need from the insects they eat, not from nectar, so the added nutrients also are unnecessary. Authorities on hummingbirds recommend that if you use a feeder, use just plain sugar and water.[15]

A hummingbird feeder should be easy to refill and keep clean. Prepared nectar can be refrigerated for 1–2 weeks before being used, but once placed outdoors it will only remain fresh for 2–4 days in hot weather, or 4–6 days in moderate weather, before turning cloudy or developing mold. If the feeder is in a shady area the nectar will last longer without spoiling. When changing the nectar, the feeder should be rinsed thoroughly with warm tap water, flushing the reservoir and ports to remove any contamination or sugar build-up. If dish soap is used, it always needs extra rinsing so that no residue is left behind. The feeder can be soaked in diluted chlorine bleach if black specks of mold appear and rinsed with clear water.

Other animals are also attracted to hummingbird feeders. It is a good idea to get a feeder that has very narrow ports, or ports with mesh-like "wasp guards", to prevent bees and wasps from getting inside where they get trapped. Orioles, woodpeckers, banaquits, and other animals are known to drink from hummingbird feeders, sometimes tipping them and draining the liquid. If this becomes a problem, it is possible to buy feeders which are specifically designed to support their extra weight and which hummingbirds will use too. If ants find your hummingbird feeder, they can be discouraged by the use of an "ant moat", which is available at specialty garden stores and online. Sticky or greasy substances used to repel ants, including petroleum jelly and commercial insect barrier products ("tanglefoot"), must be used inside an ant moat or other inaccessible location to avoid potentially fatal contamination of the birds' plumage.[16]

Sometimes a large hummingbird drives its smaller brethren away from a feeder. An effective solution is to put out a second feeder that contains a slightly lower sugar concentration. Hummingbirds can detect a feeding source that is denser in sugar by only a few percent, and the more aggressive bird will make that feeder its own. The smaller birds will flock to the remaining feeder.

In myth and culture

- The Aztec god Huitzilopochtli is often depicted as a hummingbird. The Nahuatl word huitzil (hummingbird) is an onomatopoeic word derived from the sounds of the hummingbird's wing-beats and zooming flight.

- One of the Nazca Lines, displayed at right, depicts a hummingbird.

- The Ohlone tells the story of how Hummingbird brought fire to the world. See article at the National Parks Conservation Association's website for a recounting.

- Trinidad and Tobago is known as "The land of the hummingbird," and a hummingbird can be seen on that nation's coat of arms and 1-cent coin as well as its national airline, "Caribbean Airlines".

- Many popular songs have been written under the title "Hummingbird", including separate works by B. B. King, Wilco, Leon Russell, John Mayer, Frankie Laine, Cat Stevens, Seals and Crofts, Merzbow and Yuki.

- Several companies use a hummingbird as a corporate logo. Such companies include Canadian CHC Helicopter Corporation, British Colibri, and American Hummingbird Scientific.

- In Brazil a black hummingbird of any kind, especially when found inside the house, can be superstitiously interpreted as a sign of a death in the family. The country is very receptive to the bird, though. In the Portuguese language, it is called Flower Kisser (Beija-Flor).

See also

- Hummingbird Hawk-moth (Macroglossum stellatarum)

- Hemaris, another genus of sphinx moths confused with hummingbirds

- Bird feeder, for information about hummingbird feeders.

References

- ^ Robert S. Ridgely and Paul G. Greenfield, "The Birds of Ecuador volume 2- Field Guide", Cornell University Press, 2001

- ^ Omara-Otunnu, Elizabeth. Hummingbird's Beaks Bend To Catch Insects. University of Connecticut Advance (2004-07-19).

- ^ http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/site/accounts/information/Troichilidae.html

- ^ Rodríguez-Gironés MA, Santamaría L (2004) Why Are So Many Bird Flowers Red? PLoS Biol 2(10): e350 doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0020350

- ^ Altschuler, D. L. 2003. Flower Color, Hummingbird Pollination, and Habitat Irradiance in Four Neotropical Forests. Biotropica 35(3): 344–355.

- ^ Nicolson, S. W., and P. A. Fleming. 2003. Nectar as food for birds: the physiological consequences of drinking dilute sugar solutions. Plant Syst. Evol. 238: 139–153 (2003) DOI 10.1007/s00606-003-0276-7

- ^ Rayner, J.M.V. 1995. Dynamics of vortex wakes of flying and swimming vertebrates. J. Exp. Biol. 49:131–155.

- ^ Warrick, D. R.; Tobalske, B.W. & Powers, D.R. (2005): Aerodynamics of the hovering hummingbird. Nature 435: 1094–1097 doi:10.1038/nature03647 (HTML abstract)

- ^ Skutch, Alexander F. & Singer, Arthur B. (1973): The Life of the Hummingbird. Crown Publishers, New York. ISBN 0-517-50572-X

- ^ Williamson, S. L. 2002. A Field Guide to Hummingbirds of North America (Peterson Field Guide Series). Houghton Mifflin Co., Boston. ISBN 0-618-02496-4

- ^ http://www.cbc.ca/health/story/2004/05/06/bird_fossils040506.html

- ^ Bleiweiss, Robert; Kirsch, John A. W. & Matheus, Juan Carlos (1999): DNA-DNA hybridization evidence for subfamily structure among hummingbirds. Auk 111(1): 8–19. Template:PDFlink

- ^ http://faq.gardenweb.com/faq/lists/hummingbird/2003021845028716.html

- ^ http://www.hummingbirds.net/dye.html

- ^ Shackelford, Clifford Eugene; Lindsay, Madge M. & Klym, C. Mark (2005): Hummingbirds of Texas with their New Mexico and Arizona ranges. Texas A&M University Press, College Station. ISBN 1-58544-433-2

- ^ Williamson, S. 2000. Attracting and Feeding Hummingbirds. (Wild Birds Series) T.F.H. Publications, Neptune City, New Jersey. ISBN 0-7938-3580-1

- del Hoyo, J.; Elliott, A. & Sargatal, J. (editors) (1999): Handbook of Birds of the World, Volume 5: Barn-owls to Hummingbirds. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona. ISBN 84-87334-25-3

- Gerwin, John A. & Zink, Robert M. (1998): Phylogenetic patterns in the Trochilidae. Auk 115(1): 105-118. Template:PDFlink

- McGuire, J. A., Witt, C. C., Altshuler, D. L., and Remsen Jr., J. V. 2007. Phylogenetic systematics and biogography of hummingbirds: Bayesian and maximum likelihood analyses of partitioned data and selection of an appropriate partitioning strategy. Systematic Biology, 56: 837-856.

- Meyer de Schauensee, Rodolphe (1970): A Guide to Birds of South America. Livingston, Wynnewood, PA.

- Stiles, Gary. 1981. Geographical Aspects of Bird Flower Coevolution, with Particular Reference to Central America. Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden 68:323-351.

Gallery

-

Magnificent Hummingbird—Guadalupe, Panama

-

A male Costa's Hummingbird, showing its plumage to good effect

-

Male Green Violet-ear

-

A hovering Rufous Hummingbird on Saltspring Island

-

The size of a hummingbird

-

hummingbird among flowers

-

hummingbird among flowers

-

hummingbird among flowers

-

two males fighting

-

Hummingbird among Crocosmia

-

Hummingbird is attacking a bigger bird

-

Hummingbird and honey bee to compare the sizes

-

Hummingbird at Crocosmia