Operation Epsom: Difference between revisions

EnigmaMcmxc (talk | contribs) replaced Heinrich Eberbach within in text as commander of Pz Group West with von Schweppenburg - added lengthly footnote providing evidence to support him as still being in command |

EnigmaMcmxc (talk | contribs) →28 June: slight edit to footnote, also added wiki link to it |

||

| Line 100: | Line 100: | ||

=== 28 June === |

=== 28 June === |

||

During the early hours of 28 June, a battle group of the 1st SS Panzer Division—Kampfgruppe Frey—arrived at the front and was placed under the command of the 12th SS Panzer Division. At 0810<ref name="Clark73">Clark, p. 73</ref> General [[Friedrich Dollmann|Dollmann]], commanding the German Seventh Army, ordered Hausser to divert his II SS Panzer Corps to counterattack south of Cheux.<ref>Williams, pp. 111–112</ref> Hausser replied that no counterattack could be launched until the following day, as so many of his units had yet to reach the front.<ref name="Reynolds22">Reynolds 2002, p. 22</ref> Before any plans could be finalised, the German command was thrown into disarray by Dollmann's sudden death;{{#tag:ref|Wilmot states there is no record or suggestion that Dollmann committed suicide and that Dollmann's chief of staff claims he "died of heart failure in his bathroom".<ref name="Wilmot344">Wilmot, p. 344</ref> Ellis supports this statement.<ref name="Ellis296">Ellis, p. 296</ref> However other authors dismiss this and state that Dollmann in fact took his own life.<ref name="Clark73">Clark, p. 73</ref><ref name="Reynolds22" />|group=nb}} both Field Marshals Rommel and von Rundstedt were en route to a conference with Hitler, and out of touch with the situation.<ref name="Wilmot344" /> At 1500 Hausser was appointed the new commander of the Seventh Army,<ref name="Reynolds22" /> and Willi Bittrich, the former commander of the 9th SS Panzer Division, replaced him as commander of II SS Panzer Corps (although Hausser was advised to retain control of the Corps until the following morning).<ref name="Reynolds23"/> Pending the return of Rommel to Normandy, Hausser was also to assume the role of supreme commander in the invasion area.<ref name="Reynolds23" /> At 1700 the command structure was again redrawn; Seventh Army, under Hausser, would be responsible for the invasion front facing the American army, while General [[Leo Geyr von Schweppenburg|von Schweppenburg]]'s{{#tag:ref|An organisational chart of the German command structure in the West, presented within ‘The Struggle for Europe’, shows that von Schweppenburg was still in command and not succeeded by Eberbach until 2 July. (Wilmot, p. 735) The historians Lloyd Clark and Michael Reynolds both claim that von Schweppenburg was still in command of Panzer Group West during Operation Epsom.(Clark, p. 73; Reynolds, p. 23) |

During the early hours of 28 June, a battle group of the 1st SS Panzer Division—Kampfgruppe Frey—arrived at the front and was placed under the command of the 12th SS Panzer Division. At 0810<ref name="Clark73">Clark, p. 73</ref> General [[Friedrich Dollmann|Dollmann]], commanding the German Seventh Army, ordered Hausser to divert his II SS Panzer Corps to counterattack south of Cheux.<ref>Williams, pp. 111–112</ref> Hausser replied that no counterattack could be launched until the following day, as so many of his units had yet to reach the front.<ref name="Reynolds22">Reynolds 2002, p. 22</ref> Before any plans could be finalised, the German command was thrown into disarray by Dollmann's sudden death;{{#tag:ref|Wilmot states there is no record or suggestion that Dollmann committed suicide and that Dollmann's chief of staff claims he "died of heart failure in his bathroom".<ref name="Wilmot344">Wilmot, p. 344</ref> Ellis supports this statement.<ref name="Ellis296">Ellis, p. 296</ref> However other authors dismiss this and state that Dollmann in fact took his own life.<ref name="Clark73">Clark, p. 73</ref><ref name="Reynolds22" />|group=nb}} both Field Marshals Rommel and von Rundstedt were en route to a conference with Hitler, and out of touch with the situation.<ref name="Wilmot344" /> At 1500 Hausser was appointed the new commander of the Seventh Army,<ref name="Reynolds22" /> and Willi Bittrich, the former commander of the 9th SS Panzer Division, replaced him as commander of II SS Panzer Corps (although Hausser was advised to retain control of the Corps until the following morning).<ref name="Reynolds23"/> Pending the return of Rommel to Normandy, Hausser was also to assume the role of supreme commander in the invasion area.<ref name="Reynolds23" /> At 1700 the command structure was again redrawn; Seventh Army, under Hausser, would be responsible for the invasion front facing the American army, while General [[Leo Geyr von Schweppenburg|von Schweppenburg]]'s{{#tag:ref|An organisational chart of the German command structure in the West, presented within ‘The Struggle for Europe’, shows that von Schweppenburg was still in command and not succeeded by [[Heinrich Eberbach]] until 2 July. (Wilmot, p. 735) The historians Lloyd Clark and Michael Reynolds both claim that von Schweppenburg was still in command of Panzer Group West during Operation Epsom.(Clark, p. 73; Reynolds, p. 23) Chapter IV, footnote 14, in ‘Sons of the Reich’ states that the RAF attack on von Schweppenburg’s headquarters on 10 June only slightly wounded the commander himself but his chief of staff and 16 other staff were killed.(Reynolds, p. 32) The British official campaign history of the fighting in Normandy records that von Schweppenburg was not succeeded by Eberbach until 4 July after disagreeing with Hitlers wishes on how the campaign should be conducted; a part of the same bout of dismissals which saw von Kluge replace von Rundsteadt.(Ellis, pp. 320–322|group=nb}} [[Panzer Group West]] would be responsible for the invasion front facing the Anglo-Canadian forces.<ref name="Reynolds23"/> |

||

At 0530 Scottish infantry, with tank support, launched a new assault to capture the village of Grainville-sur-Odon. After artillery shelling and close quarter street fighting, the village was secured by 1300 hours; German counterattacks followed but were repulsed.<ref>Clark, p. 74</ref> On the eastern side of the salient, at 0600 Kampfgruppe Frey, supported by Panzer IVs of the 21st Panzer Division, launched an attack north of the Odon. This reached the villages of Mouen and Tourville, but the British counterattacked from the direction of Cheux resulting in confused and heavy fighting throughout the day.<ref name="Reynolds23"/> Elsewhere on the eastern flank, British patrols had found Marcelet partially abandoned, the German front line having been pulled back towards Carpiquet.<ref name="Jackson42">Jackson, p. 42</ref> |

At 0530 Scottish infantry, with tank support, launched a new assault to capture the village of Grainville-sur-Odon. After artillery shelling and close quarter street fighting, the village was secured by 1300 hours; German counterattacks followed but were repulsed.<ref>Clark, p. 74</ref> On the eastern side of the salient, at 0600 Kampfgruppe Frey, supported by Panzer IVs of the 21st Panzer Division, launched an attack north of the Odon. This reached the villages of Mouen and Tourville, but the British counterattacked from the direction of Cheux resulting in confused and heavy fighting throughout the day.<ref name="Reynolds23"/> Elsewhere on the eastern flank, British patrols had found Marcelet partially abandoned, the German front line having been pulled back towards Carpiquet.<ref name="Jackson42">Jackson, p. 42</ref> |

||

Revision as of 15:34, 9 October 2008

| Operation Epsom | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Operation Overlord, Battle of Normandy | |||||||

An ammunition carrier of the 11th Armoured Division explodes after it was hit by a mortar round during Operation Epsom on 26 June 1944. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

2 Infantry Divisions 1 Armoured Division 1 Armoured Brigade 1 Tank Brigade |

3 SS Panzer Divisions[3] 5 Panzer battlegroups[5] 1 SS heavy tank battalion[6] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 4,020[nb 1]–4,078 casualties[nb 2] |

Over 3000 casualties[nb 3] 126 tanks knocked out[nb 4]. | ||||||

| Operation Epsom | |

|---|---|

| Operational scope | Strategic Offensive |

| Planned by | British Second Army |

| Objective | Encirclement of the city of Caen |

| Executed by | VIII Corps, Second Army |

| Outcome | Limited gains made by VIII Corps, tactically indecisive. Strategic Allied success. |

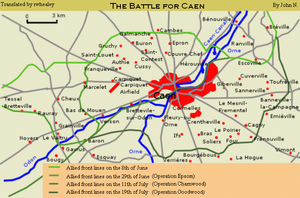

Operation Epsom was a World War II British offensive that took place between 26–30 June 1944, during the Battle of Normandy. The offensive was intended to outflank and seize the German-occupied city of Caen, which was a major Allied objective in the early stages of the invasion of northwest Europe.

Preceded by preliminary attacks intended to secure the lines of advance, Operation Epsom was launched early on the 26 June, with units of the 15th (Scottish) Infantry Division advancing behind a creeping artillery barrage. Additional bomber support had been expected, but poor weather led to this being cancelled; air support would be sporadic for much of the operation. Supported by the tanks of the 11th Armoured Division, the 15th Scottish made steady progress, and by the end of the first day had largely overrun the German outpost line, although there remained difficulties in securing the flanks. In heavy fighting over the following two days, a foothold was secured across the River Odon, and efforts were made to expand this by capturing strategic points around the salient and moving up the 43rd (Wessex) Infantry Division. However, by 30 June the British position across the river had become untenable in the face of powerful German counterattacks, and the salient was withdrawn, bringing the operation to a close.

Although the Germans had managed to contain the offensive, to do so they had been obliged to commit all their available strength, including two panzer divisions newly arrived in Normandy and earmarked for a planned offensive against British and American positions around Bayeux. Casualties were heavy on both sides, but unlike General Bernard Montgomery, Field Marshal Erwin Rommel was unable to withdraw units into reserve after the battle, as they were needed to hold the front line. The British retained the initiative, and were able to launch further operations over the following weeks, eventually capturing Caen towards the end of July.

Background

The historic Normandy town of Caen was a D-Day objective for the British 3rd Infantry Division that landed on Sword Beach beach on 6 June 1944.[11] Hampered by congestion in the beachhead that delayed the deployment of its armoured support, and forced to divert effort to attacking strongly-held German positions along the 15-kilometre (9.3 mi) route to the town, the 3rd Division was unable to assault Caen in force, and was brought to a halt short of its outskirts. Immediate follow-up attacks were unsuccessful as German resistance solidified; abandoning the direct approach, Operation Perch—a pincer attack by I and XXX Corps[12]—was launched on 7 June, with the intention of encircling Caen from the east and west.[13] I Corps, striking south out of the Orne bridgehead, was halted by the 21st Panzer Division,[14] and the attack by XXX Corps bogged down in front of Tilly-sur-Seulles, west of Caen, in the face of stiff opposition from the Panzer Lehr Division.[13] In an effort to force Panzer Lehr to withdraw or surrender,[15] and to keep operations fluid, the 7th Armoured Division pushed through a recently created gap in the German front line, and attempted to capture the town of Villers-Bocage.[16] The resulting day long battle saw the vanguard of the 7th Armoured Division withdraw from the town,[17] but by 17 June Panzer Lehr had themselves been forced back, and XXX Corps had taken Tilly-sur-Seulles.[18]

A repeated attack from the 7th Armoured Division never materialised[19] and further offensive operations were abandoned when, on 19 June, a severe storm descended upon the English Channel. The storm, which would last for three days, significantly delayed the Allied build-up.[20] Most of the convoys of landing craft and ships already at sea were driven back to ports in Britain; towed barges and other loads (including 2.5 miles (4.0 km) of floating roadways for the Mulberry harbours) were lost; and no less than 800 craft were left stranded on the Normandy beaches until the next spring tides in July.[21] Despite this, planning for a second pincer offensive began, but it was eventually decided that the bridgehead over the Orne River was too restricted to permit an attack by an entire armoured and infantry corps.[22]

The weather from 19–22 June also grounded Allied aircraft,[23] and the Germans took advantage of the respite from air attacks to improve their defensive lines, strengthening infantry positions with minefields and posting approximately seventy 88 mm guns in hedgerows and woods covering the southern approaches to Caen.[20]

Planning

On 20 June Field Marshal Erwin Rommel, commanding German forces in Normandy, was ordered by Hitler to launch a counter-offensive against the Allied lines between the towns of Caumont and Saint-Lô. The objective was to cut a corridor between the American and British armies by recapturing the city of Bayeux (taken by the British on 7 June) and the coastline beyond.[24] Four SS Panzer Divisions and one Heer Panzer Division were assigned this task. Spearheading the attack would be the 9th and 10th SS Panzer Divisions of the II SS Panzer Corps, recently arrived from the Ukraine.[25] They would be supported by the 1st and 2nd SS Panzer Divisions, and the 2nd Panzer Division.[24][26] The vast majority of the tanks used by these formations were Panzer IVs, supplemented with assault guns, Panthers and Tigers—the latter two among the most lethal and well-protected armoured vehicles in the German inventory.[27]

General Bernard Montgomery, the ground forces commander of all Allied troops in Normandy, was also preparing an offensive. Operation Epsom was initially intended to capture Caen in another pincer movement, which was to be carried out by all three Corps of the Second Army.[28] Some historians have further argued that, from ULTRA intercepts, Montgomery was aware of Rommel's planned attack and Epsom was launched to pre-empt the German offensive.[22][29]

The main role in Operation Epsom was assigned to the newly arrived British VIII Corps, which consisted of 60,244 men under the command of Lieutenant-General Richard O'Connor.[30][31][32] In a preliminary operation to take place three days before the main assault, I Corp's 51st (Highland) Infantry Division was to strike south from the Orne bridgehead, pinning down elements of the 21st Panzer Division.[33] Operation Martlet[34] (also known as Operation Dauntless)[35] was to commence on the day before Epsom; XXX Corp's 49th (West Riding) Infantry Division, supported by the 8th Armoured Brigade, was to secure VIII Corp's flank by capturing the high ground on the right of their axis of advance.[34]

Originally planned for 22 June, Epsom was postponed until 26 June to make up deficiencies in manpower and material.[36][37] VIII Corps would launch their offensive from the bridgehead gained by the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division. The operation, split into four phases, intended for the Corps to advance and capture the high ground near Bretteville-sur-Laize, south of Caen.[38][39] It would be supported by fire from 736 artillery pieces,[nb 5] three cruisers, and the monitor H.M.S. Roberts. The Royal Air Force would additionally provide close air support and a preliminary bombardment by 250 bombers.[41]

The 15th (Scottish) Infantry Division would lead the assault. During Phase I, codenamed Gout, they were tasked with taking the villages of Sainte Mauvieu and Cheux.[38] Phase II, codenamed Hangover, would see the division exploit forwards to capture several crossings over the Odon River, and the villages of Mouen and Grainville-sur-Odon.[38] As a tactical alternative, should resistance during the opening phase prove light, the 11th Armoured Division would rush the bridges over the Odon River, seizing the crossings by coup de main.[42]

During these opening two phases, the 43rd (Wessex) Infantry Division—to be reinforced on 28 June with the Guards Armoured Division's infantry brigade[43]—was to remain on the start line to provide a "firm base".[40] In Epsom's third phase, Impetigo, the 43rd Division would move forward to relieve all Scottish infantry north of the Odon.[38] The 15th Division would then assemble across the river, expanding the bridgehead by capturing several key villages. In the operation's final phase, codenamed Goitre, elements of the 43rd Division would cross the river to hold the area taken, while the 15th Division would continue to expand their bridgehead.[38] In addition, the 11th Armoured Division would attempt to force a crossing over the River Orne and advance on their final objective of Bretteville-sur-Laize.[40] The 4th Armoured Brigade, although attached to the 11th Armoured Division, was restricted to operations between the Odon and Orne, both to protect the Corps flank and to be a position to attack westwards or towards Caen as necessary.[40]

Depending on the success of VIII Corps attack, I Corps would then launch two supporting operations, codenamed Aberlour and Ottawa. The former would see the 3rd Infantry Division, supported by a Canadian infantry brigade, attack north of Caen; the latter would be a move by the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division, supported by the 2nd Canadian Armoured Brigade, to take the village and airfield of Carpiquet.[44]

The initial opposition to Epsom was expected to come from the already-depleted 12th SS Panzer Division Hitlerjugend ("Hitler Youth"),[23] along with elements of both the 21st Panzer Division and Panzer Lehr.[45]

Preliminary attacks

As planned, on 23 June elements of the 51st (Highland) Infantry Division's 152nd (Highland) Infantry Brigade launched a preliminary attack.[nb 6] Before daybreak and without an initial artillery bombardment, the Highland infantry advanced in silence towards the village of Sainte-Honorine-la-Chardronette. They took the German garrison by surprise and had complete control of the village before sunrise. During the morning the Highlanders were counterattacked by elements of the 21st Panzer Division's Kampfgruppe von Luck; fighting lasted all morning, but by midday the village was firmly in British hands.[47] This success diverted German attention and resources away from VIII Corps front, as the corps prepared for further attacks out of the Orne bridgehead.[48]

At 0415 hours on 25 June, the 49th (West Riding) Infantry Division, supported by the 8th Armoured Brigade and 250 artillery guns, launched Operation Martlet against elements of the Panzer Lehr and 12th SS Panzer divisions.[20] The operation's first objective, the village of Fontenay-le-Pesnel, was fought over all day, but stubborn German resistance prevented its capture. One infantry battalion, supported by tanks, advanced around the village to the west and took the Tessel Wood, but was subjected to a series of German counterattacks. These were blunted by British artillery fire and close air support, but by the end of the day the 49th Division had failed to achieve their ultimate objective of the village of Rauray,[49] leaving the terrain dominating the right flank of VIII Corps' intended advance still in German hands.[50] Operation Martlet did however force I SS Panzer Corps to commit the remaining tanks of 12th SS Panzer to XXX Corps' front, for a planned counterattack the following day.[51] During the night, the German forces in Fontenay-le-Pesnel withdrew to straighten the front line, and infantry from the 49th Division secured the village before dawn.[52]

Main attack

26 June

Poor weather hampered the start of Operation Epsom on 26 June—both over the battlefield itself, where rain had made the ground boggy and there was a heavy mist,[53][54] and over the United Kingdom during the early hours of the morning, resulting aircraft being grounded and the planned bombing missions being called off.[55] However, No. 83 Group RAF, already based in Normandy, were able to provide air support throughout the operation.[nb 7]

The 49th (West Riding) Infantry Division resumed Operation Martlet at 0650, although without significant artillery support as this was diverted to the main operation.[56] The Germans were able to slow the British advance, and then launched an armoured riposte.[57] This initially gained ground, but was halted when British armour moved up, and a bitter tank battle erupted in the confined terrain.[58] However, informed during the afternoon that a major British offensive was underway further east, Meyer called off his counterattack and ordered his tank companies to return to their initial positions south of Rauray.[59] During the rest of the day the 49th Division was able to make progress, halting just north of Rauray.[60]

At 0730 the 44th (Lowland) Infantry Brigade and the 46th (Highland) Infantry Brigade of the 15th (Scottish) Infantry Division, supported by the 31st Tank Brigade,[61] moved off their start lines behind a creeping barrage fired from 344 guns.[62] The 46th Brigade initially advanced without armoured support, as in bypassing the mine- and booby trap-ridden village of Le Mesnil-Patry, its tanks were forced to negotiate minefields flanking the village. The infantry advance had mixed results; one battalion[nb 8] faced only light resistance while the other[nb 9] ran into the grenadiers of the Hitler Youth Division, who had allowed the barrage to pass over their positions before opening fire.[63][64] Reuniting with the tanks at around 1000, by midday the two battalions were fighting for control of their initial objectives; Cheux and Le Haut du Bosq.[63]

The 44th Brigade, not facing the same problems as the 46th and advancing with their tank support, encountered little opposition until coming under machine gun fire at a small stream, following which German resistance was much heavier. Between 0830 and 0930, the two leading battalions[nb 10] reached their initial objectives; Sainte Mauvieu and La Gaule. After heavy combat and bitter hand to hand fighting, they believed the villages to be completely in their hands just after midday, although subsequently it was discovered that some German remnants were still holding out.[65] Tanks and infantry from the 12th SS and the 21st Panzer launched two counterattacks in an attempt to regain Sainte Mauvieu, but both were beaten off with the aid of intensive artillery fire.[66] The main German opposition in this section of their outpost line had been from elements of the 12th SS Panzer Division's 1st Battalion 26th Panzergrenadier Regiment, which had been mostly overrun, and the pioneer battalion. The Germans within Rauray, which had not been captured as planned the previous day, were able to subject the British brigades to observed artillery and indirect tank fire,[67] causing considerable casualties and destruction, especially within the village of Cheux.[66]

At 1250 one squadron from the 11th Armoured Division's reconnaissance regiment, deployed north of Cheux, was ordered to advance towards the Odon,[68] prior to an attempt to rush the bridges by the division's armoured brigade.[23] Owing to minefields near the village, debris blocking its streets, and German holdouts within the village attacking the tanks, it was not until 1400 that the regiment was finally able to make progress. By 1430 the squadron arrived on a ridge south of Cheux, were it was engaged by twenty Panzer IV's of the 12th SS Division recently arrived from the Rauray area, Tiger tanks from the 3rd Battalion, 101st Heavy SS Panzer Battalion, and additional tanks from the 21st Panzer Division.[68][69] More tanks from the 11th Armoured Division arrived, but determined German resistance halted any further advance;[68] by the end of the day the division had lost twenty-one tanks.[70] At 1800 the 15th (Scottish) Infantry Division's third infantry brigade, the 227th (Highland), was committed to the battle.[71] However, the Highlanders became bogged down fighting in support of the rest of the division, and only two companies from the 1st Battalion Gordon Highlanders made any real progress. They entered the northern outskirts of Colleville by 2100, but soon found themselves cut off by German counterattacks. After heavy and confused fighting one company was able to break out and rejoin the battalion.[68]

During the evening Field Marshal Rommel ordered that all available units from II SS Panzer Corps were to be thrown into the fight, to stop the British offensive.[72]

27 June

With no further attacks forthcoming during the night, the German command believed that the British offensive had been successfully halted, so during the early hours of 27 June, II SS Panzer Corps was ordered to resume preparations for Hitler's ordered counter strike towards Bayeux.[73]

On the right of the advance, 49th (West Riding) Infantry Division resumed its attempt to secure VIII Corps flank. The village of Rauray was finally taken at 1600 on 27 June, after further heavy fighting against the panzergrenadiers of 12th SS Panzer. This attack diverted German forces from opposing VIII Corps advance,[74] and its success denied an important observation point to the Germans, although they remained in control of an area of high ground to the south.[75]

Epsom was resumed at 0445 by the 10th Battalion Highland Light Infantry of the 227 (Highland) Infantry Brigade. With support from Churchill tanks, the battalion was to make a bid for the Odon crossing at Gavrus. However, despite heavy artillery support, the Highland Light Infantry immediately ran into stiff opposition from elements of 12th SS Panzer, and were unable to advance all day. Casualties were heavy on both sides.[76]

At 0730 the 2nd Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders, also of the 227 (Highland) Infantry Brigade, launched an attack aimed at capturing the Odon crossing at Tourmauville, northwest of the village of Baron.[77] With the available German forces already engaged by the Highland Light Infantry, the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders, supported by the 23rd Hussars, were able to advance as far as Colleville with relative ease. However, the small German garrison there, supported by 88mm guns, inflicted heavy casualties upon the British and denied them the village until the afternoon.[76] With this last obstacle dealt with, the battalion seized the bridge at Tourmauville at around 1700, and a bridgehead was established.[78] By 1900, two depleted squadrons of the 23rd Hussars, and a company of the 8th Rifle Brigade, had crossed the Odon into the bridgehead.[79]

The remainder of the 15th (Scottish) Infantry Division was positioned around Cheux and Sainte Mauvieu, and was in the process of being relieved by the 43rd (Wessex) Infantry Division. One battalion of the 43rd,[nb 11] on moving into the outskirts of Cheux, found the Scottish infantry had already moved on and the vacated position had been reoccupied by grenadiers of 12th SS Panzer. After battling to recapture the position, at 0930 the battalion was counterattacked by six Panthers of the 2nd Panzer Division.[76] The attack penetrated into the outskirts of Cheux, destroying several anti-tank guns before it was beaten off.[78][nb 12]. Further attacks by 2nd Panzer were halted,[80] but the entire front was "a mass of small engagements".[78] For the rest of the morning, and throughout the afternoon, the Scottish infantry along with the 4th and 29th Armoured Brigades expanded the salient north of the Odon, and secured the Argyll and Sutherland Highlander's rear.[81] During late evening, the men of the 159th Infantry Brigade (11th Armoured Division) were transported in trucks[82] through the narrow "Scottish Corridor"[83] to Tourville, where they dismounted and crossed the Odon on foot to reinforce the bridgehead.[82]

During the night Kampfgruppe Weidinger, a 2,500-strong battle group from the 2nd SS Panzer Division, arrived at the front, and was initially placed under the command of the Panzer Lehr Division.[84]

28 June

During the early hours of 28 June, a battle group of the 1st SS Panzer Division—Kampfgruppe Frey—arrived at the front and was placed under the command of the 12th SS Panzer Division. At 0810[85] General Dollmann, commanding the German Seventh Army, ordered Hausser to divert his II SS Panzer Corps to counterattack south of Cheux.[86] Hausser replied that no counterattack could be launched until the following day, as so many of his units had yet to reach the front.[87] Before any plans could be finalised, the German command was thrown into disarray by Dollmann's sudden death;[nb 13] both Field Marshals Rommel and von Rundstedt were en route to a conference with Hitler, and out of touch with the situation.[88] At 1500 Hausser was appointed the new commander of the Seventh Army,[87] and Willi Bittrich, the former commander of the 9th SS Panzer Division, replaced him as commander of II SS Panzer Corps (although Hausser was advised to retain control of the Corps until the following morning).[1] Pending the return of Rommel to Normandy, Hausser was also to assume the role of supreme commander in the invasion area.[1] At 1700 the command structure was again redrawn; Seventh Army, under Hausser, would be responsible for the invasion front facing the American army, while General von Schweppenburg's[nb 14] Panzer Group West would be responsible for the invasion front facing the Anglo-Canadian forces.[1]

At 0530 Scottish infantry, with tank support, launched a new assault to capture the village of Grainville-sur-Odon. After artillery shelling and close quarter street fighting, the village was secured by 1300 hours; German counterattacks followed but were repulsed.[90] On the eastern side of the salient, at 0600 Kampfgruppe Frey, supported by Panzer IVs of the 21st Panzer Division, launched an attack north of the Odon. This reached the villages of Mouen and Tourville, but the British counterattacked from the direction of Cheux resulting in confused and heavy fighting throughout the day.[1] Elsewhere on the eastern flank, British patrols had found Marcelet partially abandoned, the German front line having been pulled back towards Carpiquet.[91]

South of the Odon, at 0900 the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders advanced out of the bridgehead won the previous day, with the aim of capturing a bridge north of the village of Gavrus. Heavy fighting took place into the afternoon before both village and bridge were in Scottish hands.[91] Meanwhile infantry from the 11th Armoured Division expanded the bridgehead by taking the village of Baron,[92] and the 23rd Hussars, with infantry support, advanced on Hill 112. Having secured its northern slope and dislodged the defenders from its crest, they were unable to advance further due to stiff resistance from German forces dug in on the hill's reverse slope.[93] The battered hussars were relieved at 1500 by the 3rd Royal Tank Regiment, but neither side was able to take complete control of the hill.[93]

29–30 June

With the weather now improving, Hausser's preparations for his counter-stroke were subjected to continual harassment from Allied aircraft, and during the afternoon of 29 June an officer of 9th SS Panzer Division was captured near Rauray, carrying a map and notebook with details of Hausser's plan of attack.[94] Nevertheless, the Germans launched their attack against the 15th (Scottish) Infantry Division's right flank on the evening of 29 June.[95] Despite being hit hard by British aircraft, artillery and anti-tank fire, some German tanks penetrated 2 miles (3.2 km) into the British lines. By nightfall the attack was being largely held, although at a high cost; by the end of the third day the 15th Division had suffered more than 2,300 casualties.[96]

The British salient across the Odon was cramped and under fire from several sides, making it difficult to introduce fresh units.[4] On 30 June, a bright summer's day, Allied fighter-bombers caused heavy casualties to German armour approaching positions of the 11th Armoured Division,[97] but during the evening, the Germans succeeded in recapturing Hill 112. With this commanding position lost, the British were forced to abandon the salient and pull back to the north bank of the Odon; Operation Epsom was closed down.[97]

Results and aftermath

The Germans achieved a defensive success in containing the Allied offensive, while the cost to the British of Operation Epsom was more than 4,000 infantry casualties.[8] However, the Germans had been forced to commit their armoured units piecemeal to meet threats as they developed, and to counterattack at a disadvantage.[4] They had lost more than 120 tanks,[98] and their forces were significantly disrupted and worn down.[4] Furthermore, as there were few infantry units available, the armour had to assume the defensive role, being forced to remain in the front line rather than pulling back to rest and refit.[97]

Using information from ULTRA,[99] and the fortuitous capture of a set of German orders, Montgomery had been able to force the Germans to react to Allied moves.[100] As Hausser's units were forming up to attack the salient across the Odon river, the British 11th Armoured Division was being withdrawn into reserve. The Germans had thrown everything into trying to contain the current offensive, while the British were preparing for the next.[97]

A few days after Epsom ended, Operation Charnwood captured the northern half of Caen in a frontal assault, with the remainder of the town falling to the British during Operation Goodwood in July.[101]

Notes

- Footnotes

- ^ Casualty figures for the 15th (Scottish) Infantry Division from 27 June-2 July are 2,331 casualties (288 killed, 1,638 wounded and 794 missing). No dates are provided, but the 11th Armoured Division and 43rd (Wessex) Infantry Division lost a total of 1,256 men between them during Epsom, with 257 men killed within 11th Armoured.[7]

- ^ 470 men killed, 2,187 wounded, 706 missing between June 26 and June 30. 488 killed and wounded; and 227 missing on 1 July.[8]

- ^ While overall German losses during Epsom amounted to over 3000 men. For the 9th SS Panzer Division they amount to 1,145, 10thSS - 571 and 12th SS - 1,244.[9]

- ^ 126 tanks were knocked out between 26 June and midnight 1 July, excluding "possibles". 41 Panthers and 25 Tigers are claimed within this total.[10]

- ^ 552 field guns, 112 medium guns, 48 heavy guns and 24 heavy AA guns. Broken down into Corps; I Corps: 216 field guns, 32 medium guns and 16 heavy guns. VIII Corps: 240 field guns, 16 medium guns, 16 heavy guns and 24 heavy AA guns. XXX Corps: 96 field guns, 64 medium guns and 16 heavy guns.[40]

- ^ 5th Battalion, The Cameron Highlanders; 5th Battalion, Seaforth Highlanders; 13th/15th Hussars, with artillery and engineer support.[46]

- ^ No. 83 Group RAF flew over 500 sorties in support of Operation Epsom, despite reduced effectiveness due to the weather.[55]

- ^ 2nd Battalion, Glasgow Highlanders

- ^ 9th Battalion, The Cameronians

- ^ 6th Battalion, The Royal Scots Fusiliers and the 8th Battalion, The Royal Scots

- ^ 5th Battalion Duke of Cornwall's Light Infantry[78]

- ^ One tank was able to flee, another turned over and four were knocked by PIATs.[76]

- ^ Wilmot states there is no record or suggestion that Dollmann committed suicide and that Dollmann's chief of staff claims he "died of heart failure in his bathroom".[88] Ellis supports this statement.[89] However other authors dismiss this and state that Dollmann in fact took his own life.[85][87]

- ^ An organisational chart of the German command structure in the West, presented within ‘The Struggle for Europe’, shows that von Schweppenburg was still in command and not succeeded by Heinrich Eberbach until 2 July. (Wilmot, p. 735) The historians Lloyd Clark and Michael Reynolds both claim that von Schweppenburg was still in command of Panzer Group West during Operation Epsom.(Clark, p. 73; Reynolds, p. 23) Chapter IV, footnote 14, in ‘Sons of the Reich’ states that the RAF attack on von Schweppenburg’s headquarters on 10 June only slightly wounded the commander himself but his chief of staff and 16 other staff were killed.(Reynolds, p. 32) The British official campaign history of the fighting in Normandy records that von Schweppenburg was not succeeded by Eberbach until 4 July after disagreeing with Hitlers wishes on how the campaign should be conducted; a part of the same bout of dismissals which saw von Kluge replace von Rundsteadt.(Ellis, pp. 320–322

- Citations

- ^ a b c d e f Reynolds 2002, p. 23

- ^ Clark, p. 73

- ^ a b Clark, p. 27

- ^ a b c d Williams, p. 123

- ^ Clark, pp. 24, 63, 73

- ^ Clark, p. 28

- ^ Clark, p. 109

- ^ a b Jackson, pp. 37, 40, 44, 53, 55 & 59

- ^ Clark, pp. 107–109

- ^ Jackson, p. 59

- ^ Williams, p. 24

- ^ Ellis, p. 247

- ^ a b Forty, p. 36

- ^ Ellis, p. 250

- ^ Ellis, p. 254

- ^ Taylor, p. 10

- ^ Taylor, p. 76

- ^ Forty, p. 97

- ^ Ellis, p. 255

- ^ a b c Williams, p. 114

- ^ Wilmot, p. 322

- ^ a b Williams, p. 113

- ^ a b c Williams, p. 118

- ^ a b Wilmot, p. 334

- ^ Reynolds 2002, p. 13

- ^ Wilmot, map p. 321

- ^ Williams, p. 112

- ^ Clark, pp. 20–21

- ^ Wilmot, p. 342

- ^ Jackson, p. 22

- ^ Jackson, p. 27

- ^ Clark, p. 34

- ^ Clark, pp. 20–21

- ^ a b Clark, p. 21

- ^ Ellis, p. 275

- ^ Clark, p. 20

- ^ Jackson, p. 22

- ^ a b c d e Clark, pp. 31–32

- ^ Jackson, p. 18

- ^ a b c d Jackson, pp. 30–31

- ^ Clark, p. 29

- ^ Jackson, p. 29

- ^ Jackson, p. 40

- ^ Stacey, p. 150

- ^ Clark, p. 24

- ^ Ellis, pp. 274–275

- ^ Ellis, p. 275

- ^ Clark, p. 37

- ^ Clark, p. 39

- ^ Williams, pp. 115–116

- ^ Meyer, p. 244

- ^ Clark, p. 40

- ^ Wilmot, p. 343

- ^ Clark, p. 45

- ^ a b Ellis, p. 277

- ^ Clark, p. 42

- ^ Clark, pp. 42–43

- ^ Meyer, p. 244

- ^ Clark, p. 43

- ^ Clark, p. 45

- ^ Jackson, p. 32

- ^ Reynolds 2002, pp. 19–20

- ^ a b Jackson, pp. 32–33

- ^ Reynolds 2002, p. 20

- ^ Jackson, p. 33

- ^ a b Ellis, p. 278

- ^ Clark, pp. 46–47

- ^ a b c d Jackson, p. 34–35

- ^ Clark, p. 51

- ^ Fortin, p. 15

- ^ Ellis, p. 278

- ^ Wilmot, p. 343

- ^ Wilmot, pp. 343–344

- ^ Clark, p. 65

- ^ Clark, pp. 65–67

- ^ a b c d Clark, p. 68

- ^ Clark, p. 67

- ^ a b c d Jackson, p. 39

- ^ Saunders, p. 20

- ^ Clark, p. 96

- ^ Jackson, pp. 39–40

- ^ a b Jackson, p. 40

- ^ Clark, p. 72

- ^ Reynolds 2002, p. 21

- ^ a b Clark, p. 73

- ^ Williams, pp. 111–112

- ^ a b c Reynolds 2002, p. 22

- ^ a b Wilmot, p. 344

- ^ Ellis, p. 296

- ^ Clark, p. 74

- ^ a b Jackson, p. 42

- ^ Fortin, p. 15

- ^ a b Jackson, p. 41

- ^ Wilmot, p.345

- ^ Williams, p. 121

- ^ Williams, p. 122

- ^ a b c d Williams, p. 124

- ^ Jackson, p. 59

- ^ Williams, p. 175

- ^ Williams, p. 126

- ^ Williams, p. 131

References

- Clark, Lloyd. Operation Epsom. Battle Zone Normandy. The History Press Ltd. ISBN 0-75093-008-X.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Unknown parameter|origdate=ignored (|orig-date=suggested) (help) - Ellis, Major L.F. (2004). Victory in the West Volume I: The Battle of Normandy. History of the Second World War, United Kingdom Military Series, Official Campaign History. Naval & Military Press Ltd. ISBN 1-84574-058-0.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|origdate=ignored (|orig-date=suggested) (help) - Fortin, Ludovic (2004). British Tanks In Normandy. Histoire & Collections. ISBN 2-91523-933-9.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|coauthors=and|origdate=(help) - Jackson, G.S. (2006). 8 Corps: Normandy to the Baltic. MLRS Books. ISBN 978-1-905696-25-3.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|origdate=ignored (|orig-date=suggested) (help) - Meyer, Kurt (2005). Grenadiers: The Story of Waffen SS General Kurt "Panzer" Meyer. Stackpole Books,U.S.; New Ed edition. ISBN 0-81173-197-9.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Unknown parameter|origdate=ignored (|orig-date=suggested) (help) - Reynolds, Michael (2002). Sons of the Reich: The History of II SS Panzer Corps in Normandy, Arnhem, the Ardennes and on the Eastern Front. Casemate Publishers and Book Distributors. ISBN 0-97117-093-2.

- Stacey, Colonel Charles Perry. "Official History of the Canadian Army in the Second World War: Volume III. The Victory Campaign: The operations in North-West Europe 1944-1945" (PDF). The Queen's Printer and Controller of Stationery Ottawa. Retrieved 2008-08-20.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|origdate=ignored (|orig-date=suggested) (help) - Taylor, Daniel (1999). Villers-Bocage Through the Lens. After After the Battle. ISBN 1-87006-707-X.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|coauthors=and|origdate=(help) - Williams, Andrew (2004). D-Day to Berlin. Hodder. ISBN 0340833971.

- Wilmot, Chester (1997). The Struggle For Europe. Wordsworth Editions Ltd. ISBN 1-85326-677-9.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|origdate=ignored (|orig-date=suggested) (help)