Abdy baronets and Quark: Difference between pages

Robina Fox (talk | contribs) m →Abdy Baronets of Felix Hall, Essex: link repair |

m →Electric charge: addition: even for the quark pairs that are detected in high-energy physics experiments. |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{otheruses}} |

|||

There have been four Abdy baronetcies: |

|||

[[Image:Standard Model of Elementary Particles.svg|thumb|250px|Six of the particles in the [[Standard Model]] are quarks.]] |

|||

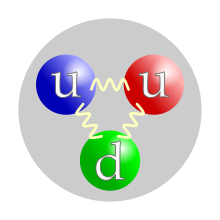

In [[physics]], a '''quark''' ({{IPAEng|kwɔrk}}, {{IPAEng|kwɑːk}} or {{IPAEng|kwɑːrk}}) is a type of [[subatomic particle]].<ref>{{cite web |title=Fundamental Particles |publisher=[[Oxford Physics]] |url=http://www.physics.ox.ac.uk/documents/pUS/dIS/fundam.htm |accessdate=2008-06-29}}</ref> Quarks are [[elementary particle|elementary]] [[fermion]]ic particles which [[strong interaction|strongly interact]] due to their [[color charge]].<ref>{{cite web |title=Quark (subatomic particle) |publisher=[[Encyclopedia Britannica]] |url=http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/486323/quark |accessdate=2008-06-29}}</ref> Due to the phenomenon of [[color confinement]], quarks are never found on their own: they are always bound together in [[composite particle]]s named [[hadron]]s.<ref name="Kim"/> The most common hadrons are the [[proton]] and the [[neutron]], which are the components of [[atomic nucleus|atomic nuclei]]. |

|||

There are six different types of quarks, known as ''[[flavour (particle physics)|flavor]]s'': [[Up quark|up]] (symbol: {{SubatomicParticle|Up quark}}), [[Down quark|down]] ({{SubatomicParticle|Down quark}}), [[Charm quark|charm]] ({{SubatomicParticle|Charm quark}}), [[Strange quark|strange]] ({{SubatomicParticle|Strange quark}}), [[Top quark|top]] ({{SubatomicParticle|Top quark}}), and [[Bottom quark|bottom]] ({{SubatomicParticle|Bottom quark}}).<ref name="Hyperphysics">{{cite web |title=Quarks |publisher=[[HyperPhysics]] |url=http://hyperphysics.phy-astr.gsu.edu/hbase/Particles/quark.html |accessdate=2008-06-29}}</ref> |

|||

==Abdy Baronets of Felix Hall, Essex== |

|||

The lightest flavors, the up quark and the down quark, are generally stable and are very common in the universe as they are the constituents of protons and neutrons. The more massive charm, strange, top and bottom quarks are unstable and rapidly [[particle decay|decay]]; these can only be produced as quark-pairs under [[high energy physics|high energy]] conditions, such as in [[particle accelerator]]s and in [[cosmic ray]]s. For every quark flavor there is an [[antiparticle]], called an antiquark, that differs from quarks only in that some of their properties have the opposite sign. |

|||

:Created in the [[Baronetage of England]] 14 July 1641 |

|||

*<span id="Sir Thomas Abdy, 1st Baronet, of Felix Hall">'''Sir Thomas Abdy, 1st Baronet'''</span> (1612 – 14 January 1686), was an English lawyer and landowner, the son of [[Anthony Abdy (1579-1640)|Anthony Abdy]] and Abigail Campbell. Abdy was baptized on 18 May 1612, and educated at [[Trinity College, Cambridge]], to which he was admitted in 1629 as a Fellow Commoner. He became a member of [[Lincoln's Inn]] in 1632. Abdy married Mary Corsellis on 1 February 1638 at [[St Peter Le Poer]], [[London]], by whom he had three children, James (b. 1639, d. young), Rachael (b. 1640), and Abigail (b. 1644). Abdy inherited the family seat of [[Felix Hall]], [[Essex]], upon his father's death in 1640, and was created a baronet in the following year, on 14 July 1641. Mary died on 6 April 1645 and was buried at [[Kelvedon]]. On 16 January 1647, Sir Thomas made a second marriage, at [[St Bartholomew the Less]], London, to Anne Soame, daughter of Sir Thomas Soame, an alderman of London. They had ten children: [[Sir Anthony Abdy, 2nd Baronet|Anthony]] (1655–1704), Thomas (d. 1697), William (d. 1682), Joanna (1654–1710), Alice (b. 1661), Anna (d. 1692), Mary, Judith, Sarah, and Elizabeth. In 1651, Abdy was named [[High Sheriff of Essex]], but continued to prosper after the [[English Restoration|Restoration]], seeking a lease from the Crown soon afterwards of the sugar duty. He inherited the property of his cousin Sir Christopher Abdy of Uxbridge in 1679, the same year in which his wife Anne died, on 16 June 1679. Abdy died on 14 January 1686 and was buried at [[Theydon Garnons]], Essex, being succeeded by his son Anthony. His monument at Theydon Garnons was, perhaps, designed by William Stanton. |

|||

*<span id="Sir Anthony Abdy, 2nd Baronet">'''Sir Anthony Abdy, 2nd Baronet'''</span> (1655 – 2 April 1704) was an English landowner, eldest surviving son of the 1st Baronet. Baptized on 4 July 1655, he was educated, like his father, at Trinity College, to which he was admitted in 1672. He married Mary Milward, daughter of Rev. Dr. Richard Milward, on 9 June 1682, by whom he had thirteen children: Thomas (d. young), Joanna (1686–1765), Elizabeth (b. 1687), [[Sir Anthony Thomas Abdy, 3rd Baronet|Anthony Thomas]] (1688–1733), [[Sir William Abdy, 4th Baronet|William]] (1689–1750), Rachel (b. 1690), Charles (b. 1693), Richard (b. 1694), Alice (b. 1695), Margaret (1696–1779), Martha (1700–1780), Anna (d. 1738), and Mary (b. c.1703). Anthony succeeded to the baronetcy in 1686 on the death of his father, and died on 2 April 1704. He was buried at Kelvedon, where his monument was designed by [[Edward Stanton]], and was succeeded by his son Anthony Thomas in the baronetcy. |

|||

*<span id="Sir Anthony Thomas Abdy, 3rd Baronet">'''Sir Anthony Thomas Abdy, 3rd Baronet'''</span> (1688 – 11 June 1733), English lawyer and landowner, was the eldest surviving son of the 2nd Baronet, and succeeded to the baronetcy in 1704. Abdy was admitted to Lincoln's Inn on 9 October 1708. His first wife was Mary Gifford, by whom he had no children. By his second wife, Charlotte Barndardiston (d. 19 February 1731), daughter of [[Sir Thomas Barnardiston, 3rd Baronet]], he had one daughter, Charlotte, who married John Williams, son of Sir John Williams, [[Lord Mayor of London]]. By his third wife, a Miss Williams, he likewise had no male issue, and upon his death in 1733, was succeeded in the baronetcy by his brother William. |

|||

*<span id="Sir William Abdy, 4th Baronet">'''Sir William Abdy, 4th Baronet'''</span> (1689 – 25 January 1750), English landowner, was the second surviving son of the 2nd Baronet. He married the daughter of Philip Stotherd, and by her had three sons, [[Sir Anthony Thomas Abdy, 5th Baronet|Anthony Thomas]] (c.1720–1775), Rev. Stotherd (d. 5 April 1773), and Capt. [[Sir William Abdy, 6th Baronet|William]], and several daughters, including Charlotte Elizabeth, who married Rev. Dr. Thomas Rutherforth on 11 April 1752. He succeeded to the baronetcy upon the death of his brother in 1733. On his own death in 1750, he was succeeded by his eldest son, Anthony Thomas. |

|||

*'''[[Sir Anthony Abdy, 5th Baronet|Sir Anthony Thomas Abdy, 5th Baronet]]''', [[King's Counsel|KC]] (c.1720 – 16 April 1775), English lawyer and landowner, was the eldest son of the 4th Baronet. He became a [[king's counsel]], and represented [[Knaresborough (UK Parliament constituency)|Knaresborough]] in the [[British House of Commons|House of Commons]] from 1763 until his death. He left his estates to his nephew, Thomas Abdy Rutherforth, while the baronetcy passed to his brother William. |

|||

*<span id="Sir William Abdy, 6th Baronet">Captain '''Sir William Abdy, 6th Baronet'''</span> (c.1732 – 21 July 1803), English landowner and naval officer, was the third surviving son of the 4th Baronet. He became a [[captain]] in the [[Royal Navy]] before inheriting the baronetcy from his brother Sir Anthony in 1775 (the second brother, Rev. Stotherd, having died in 1773). He married Mary Gordon, by whom he had one son, [[Sir William Abdy, 7th Baronet|William]] (1779–1868). |

|||

*<span id="Sir William Abdy, 7th Baronet">'''[[Sir William Abdy, 7th Baronet]]'''</span> (1779 – 16 April 1868), English landowner, was the only son of the 6th Baronet. He was educated at [[Eton College|Eton]], and succeeded to the baronetcy in 1803. Abdy served in the militia and was an active magistrate for [[Surrey]], and briefly served as a Member of Parliament. He married [[Anne Wellesley]] in 1806, but the two were divorced in 1816, without issue. The baronetcy became extinct upon his death. |

|||

The [[quark model]] was independently proposed by physicists [[Murray Gell-Mann]] and [[George Zweig]] in 1964.<ref name="Carithers">{{cite journal|title=Discovery of the Top Quark |author=B. Carithers, P. Grannis |url=http://www.slac.stanford.edu/pubs/beamline/25/3/25-3-carithers.pdf |accessdate=2008-09-23}}</ref> There was little evidence for the theory until 1968, when electron-proton scattering experiments indicated the existence of substructure within the proton resembling three 'sphere-like' regions within the proton.<ref name="Bloom">{{cite journal |title=High-Energy Inelastic ''e''-''p'' Scattering at 6° and 10° |year=1969 |author=E. D. Bloom |journal=[[Physical Review Letters]] |volume=23 |pages=p.930 |doi=10.1103/PhysRevLett.23.930}}</ref><ref name="Breidenbach">{{cite journal |title=Observed Behavior of Highly Inelastic Electron-Proton Scattering |year=1969 |author=M. Breidenbach |journal=[[Physical Review Letters]] |volume=23 |pages=p.935 |doi=10.1103/PhysRevLett.23.935}}</ref> By 1995, when the top quark was observed at [[Fermilab]], all the six flavors had been observed. Since quarks are not found in isolation, their properties can only be deduced from experiments on hadrons.<ref name="Kim"/> An exception to this rule is the [[top quark]], which decays so rapidly that it does not produce hadrons at all, and instead is observed through the identification of the particles it has decayed into.<ref name=Garberson/> |

|||

==Abdy Baronets of Albyns, Essex (1st creation)== |

|||

:Created in the [[Baronetage of England]] 9 June 1660 |

|||

*[[Sir Robert Abdy, 1st Baronet]] |

|||

*[[Sir John Abdy, 2nd Baronet]] |

|||

*[[Sir Robert Abdy, 3rd Baronet]] MP for Essex 1727-1748 |

|||

*[[Sir John Abdy, 4th Baronet]] MP for Essex 1748-1759 |

|||

:Extinct on his death |

|||

== History == |

|||

==Abdy Baronets of Moores, Essex== |

|||

[[Image:Murray Gell-Mann.jpg|right|thumb|upright|[[Murray Gell-Mann]] in 2007. Nobel laureates Gell-Mann and George Zweig first proposed the quark model in 1964.]] |

|||

:Created in the [[Baronetage of England]] 22 June 1660 |

|||

The quark theory was first postulated by physicists [[Murray Gell-Mann]] and [[George Zweig]] in 1964.<ref name="Carithers" /> At the time of the theory's initial proposal, the "[[particle zoo]]" consisted of several leptons and many different hadrons. Gell-Mann and Zweig developed the quark theory to explain the hadrons; they proposed that various combinations of quarks and antiquarks were the components of the hadrons, which were at the time considered to be indivisible.<ref name="Staley">{{cite book |title=The Evidence for the Top Quark |year=2004 |author=K.W. Staley |publisher=[[Cambridge University Press]] |isbn=0521827108 |pages=p.15}}</ref> |

|||

*[[Sir John Abdy, 1st Baronet]] |

|||

:Extinct on his death |

|||

The Gell-Mann–Zweig model predicted three quarks, which they named ''up'', ''down'' and ''strange'' ({{SubatomicParticle|Up quark}}, {{SubatomicParticle|Down quark}}, {{SubatomicParticle|Strange quark}}). At the time, the pair of physicists ascribed various properties and values to the three new proposed particles, such as [[electric charge]] and [[spin (physics)|spin]].<ref name="CERN">{{cite web |title=Funny Quarks |publisher=[[CERN]] |url=http://pdg.web.cern.ch/pdg/cpep/quark_fun.html |accessdate=2008-09-24}}</ref> The initial reaction of the physics community to the proposal was mixed, many having reservations regarding the actual physicality of the quark concept. They believed the quark was merely an abstract concept that could be used temporarily to help explain certain concepts that were not well understood, rather than an actual entity that existed in the way that Gell-Mann and Zweig had envisioned.<ref name="Staley" /> |

|||

==Abdy Baronets, of Albyns (1850)== |

|||

[[Image:Baronet Abdy of Albyns.jpg|right|120px]] |

|||

:Created in the [[Baronetage of the United Kingdom]] 8 January 1850 |

|||

*<span id="Sir Thomas Abdy, 1st Baronet, of Albyns">'''[[Sir Thomas Abdy, 1st Baronet, of Albyns|Sir Thomas Neville Abdy, 1st Baronet]]'''</span> (1810–1877) was a British politician. He represented [[Lyme Regis (UK Parliament constituency)|Lyme Regis]] in Parliament from 1847 to 1852, and was created a baronet in 1850. Abdy was chosen [[High Sheriff of Essex]] in 1875. By his wife Hariot Alston, he had one daughter, Grace (d. 1923), who married Lord Albert Leveson-Gower, and four sons, [[Sir William Abdy, 2nd Baronet|William]] (1844–1910), [[Sir Anthony Charles Abdy, 3rd Baronet|Anthony Charles]] (1848–1921), Robert John (1850–1893), and [[Sir Henry Abdy, 4th Baronet|Henry]] (1853–1921). |

|||

*<span id="Sir William Abdy, 2nd Baronet">'''Sir William Neville Abdy, 2nd Baronet'''</span> (18 June 1844 – 9 August 1910) was the eldest son of Sir Thomas Abdy, 1st Baronet. He succeeded his father in 1877. Educated at [[Merton College, Oxford]], he served as a [[Justice of the Peace]] for Essex, and was named High Sheriff of the county in 1884. He married three times, but had no children, and was succeeded by his brother Anthony. |

|||

*<span id="Sir Anthony Charles Abdy, 3rd Baronet">'''Sir Anthony Charles Sykes Abdy, 3rd Baronet'''</span> (19 September 1848 – 17 May 1921) was a British soldier, the second son of Sir Thomas Abdy, 1st Baronet. He served in the [[2nd Life Guards]], rising to the rank of [[captain]], and fought in the [[1882 Anglo-Egyptian War]]. Abdy was a military attaché in Vienna in 1885. He married Hon. Alexandrina Victoria Macdonald, daughter of [[Godfrey Macdonald, 4th Baron Macdonald]] and Maria Anne Wyndham, on 11 November 1886. They had three daughters: Grace Lillian (1887–?), married [[Henry Butler, 8th Earl of Lanesborough]] in 1917, Violet (1892–1957), married Hugh Godsal in 1925, and Constance Mary (1895–?), married Harold Frederick Andorsen in 1941. Upon the death of his elder brother William in 1910 without children, Anthony succeeded to the baronetcy. |

|||

*<span id="Sir Henry Abdy, 4th Baronet">'''Sir Henry Beadon Abdy, 4th Baronet'''</span> (13 July 1853 – 1 December 1921) was the fourth son of Sir Thomas Abdy, 1st Baronet. He married Anna Adele Coronna (d. 21 March 1920) on 22 March 1891, and had two sons by her: William Neville (1895–1911), who predeceased him, and [[Sir Robert Abdy, 5th Baronet|Robert]] (1896–1976). He succeeded to the baronetcy when his brother Anthony died in May 1921, leaving only daughters, but Sir Henry died that December, and was succeeded by his only surviving son. |

|||

*<span id="Sir Robert Abdy, 5th Baronet">'''Sir Robert Henry Edward Abdy, 5th Baronet'''</span> (11 September 1896 – 17 November 1976) was the second son of Sir Henry Abdy, 4th Baronet. He was educated at [[Charterhouse School]] and the [[Royal Military Academy Sandhurst]], and subsequently became a [[lieutenant]] in the [[15th/19th The King's Royal Hussars]]. Sir Robert married Iya De Gay on 23 June 1923, but they were divorced in 1928. Two years later, on 10 February 1930, he married Lady Helen Diana Bridgeman, daughter of the [[Orlando Bridgeman, 5th Earl of Bradford|5th Earl of Bradford]]. They had one son, [[Sir Valentine Abdy, 6th Baronet|Valentine]] (b. 1937), before being divorced in 1962. Sir Robert's third wife was Jane Noble, whom he married on 5 September 1962 and divorced in 1973. |

|||

*<span id="Sir Valentine Abdy, 6th Baronet">'''Sir Valentine Robert Duff Abdy, 6th Baronet'''</span> (b. 11 September 1937) is the only son of Sir Robert Abdy, 5th Baronet. Educated at [[Eton College]], he was a European Representative at the [[Smithsonian Institute]], 1983–1995, serving in 1995 as a member of the National Board. He was Special Advisor to the International Fund for the Promotion of Culture, [[UNESCO]] in 1991. He has been a member of the Organising Committee, Cité de l’Espace, Toulouse since 1999. Valentine married Mathilde Marie Alexe Christianne de la Ferté in 1971, and they had one son, Robert Etienne Eric Abdy (b. 1978), before divorcing in 1982. |

|||

In less than a year, extensions to the Gell-Mann–Zweig model were proposed when another duo of physicists, [[Sheldon Lee Glashow]] and [[James Bjorken]], predicted the existence of a fourth flavor of quark, which they referred to as ''charm'' ({{SubatomicParticle|Charm quark}}). The addition was proposed because it expanded the power and self consistency of the theory: it allowed a better description of the [[weak interaction]] (the mechanism that allows quarks to [[particle decay|decay]]); equalized the number of quarks with the number of known leptons; and implied a mass formula that correctly reproduced the masses of the known mesons.<ref>{{cite journal |year=1964 |author=B. J. Bjorken, S. L. Glashow |journal=Physics Letters |volume=11 |pages=p.255 |title=Elementary Particles and SU(4) |doi=10.1016/0031-9163(64)90433-0}}</ref> |

|||

The [[Heir Apparent]] is the present holder's son Robert Etienne Eric Abdy (b. 1978) |

|||

In 1968, [[deep inelastic scattering]] experiments at the [[Stanford Linear Accelerator Center]] showed that the proton had substructure.<ref>{{cite web |title=The Road to the Nobel Prize |publisher=[[Hue University]] |author=J.I. Friedman |url=http://www.hueuni.edu.vn/hueuni/en/news_detail.php?NewsID=1606&PHPSESSID=909807ffc5b9c0288cc8d137ff063c72 |accessdate=2008-09-29}}</ref><ref name="Bloom" /><ref name="Breidenbach"/> However, whilst the concept of hadron substructure had been proven, there was still apprehension towards the quark model: the substructures became known at the time as [[parton (particle physics)|parton]]s, (a term proposed by Nobel Laureate [[Richard Feynman]], and supported by some experimental project reports<ref>Richard P. Feynman, ''Proceedings of the 3rd Topical Conference on High Energy Collision of Hadrons'', Stony Brook, N. Y. (1969) </ref>,<ref>CTEQ Collaboration, S. Kretzer et al., "CTEQ6 Parton Distributions with Heavy Quark Mass Effects", Phys. Rev. D69, 114005 (2004).</ref>), but it "was unfashionable to identify them explicitly with quarks".<ref name="Griffiths">{{cite book |author=D. J. Griffiths |title=Introduction to Elementary Particles |publisher=[[John Wiley & Sons]] |year=1987 |isbn=0-471-60386-4 |pages=p.42}}</ref> These partons were later identified as up and down quarks.<ref>{{cite book |title=The God Particle |author=L. M. Lederman, D. Teresi |pages=p.208 |year=2006 |publisher=[[Mariner Books]] |isbn=0618711686}}</ref> Their discovery also validated the existence of a third strange quark, because it was necessary to the model Gell-Mann and Zweig had proposed.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://abyss.uoregon.edu/~js/21st_century_science/short_history_of_particles.html|title=Short History of Particles|first=James|last=Schombert|publisher=[[University of Oregon]]|accessdate=5 October|accessyear=2008}}</ref> |

|||

==References== |

|||

*{{Rayment-bd}} |

|||

*''Burke's Peerage and Baronetage'' 1924 |

|||

*[http://www.thepeerage.com/ thePeerage.com] |

|||

*‘ABDY, Sir William Neville’, Who Was Who, A & C Black, 1920–2007; online edn, Oxford University Press, Dec 2007 |

|||

*‘ABDY, Captain Sir Anthony (Charles Sykes)’, Who Was Who, A & C Black, 1920–2007; online edn, Oxford University Press, Dec 2007 |

|||

*‘ABDY, Sir Henry Beadon’, Who Was Who, A & C Black, 1920–2007; online edn, Oxford University Press, Dec 2007 |

|||

*‘ABDY, Sir Robert (Henry Edward)’, Who Was Who, A & C Black, 1920–2007; online edn, Oxford University Press, Dec 2007 |

|||

*‘ABDY, Sir Valentine (Robert Duff)’, Who's Who 2008, A & C Black, 2008; online edn, Oxford University Press, Dec 2007 |

|||

In a 1970 paper,<ref>{{cite journal |author=S. L. Glashow, J. Iliopoulos, L. Maiani |title=Weak Interactions with Lepton-Hadron Symmetry |journal=Physical Review D |year=1970 |url=http://prola.aps.org/abstract/PRD/v2/i7/p1285_1 |accessdate=2008-09-29|doi=10.1103/PhysRevD.2.1285 |volume=2 |pages=1285}}</ref> Glashow, [[John Iliopoulos]], and [[Luciano Maiani]] gave more compelling theoretical arguments for the as-yet undiscovered charm quark.<ref>{{cite book |author=D. J. Griffiths |title=Introduction to Elementary Particles |publisher=[[John Wiley & Sons]] |year=1987 |isbn=0-471-60386-4 |pages=p.44}}</ref> The number of proposed quark flavors grew to the current six in 1973, when [[Makoto Kobayashi (physicist)|Makoto Kobayashi]] and [[Toshihide Maskawa]] noted that the experimental observation of [[CP violation]] could be explained if there were another pair of quarks. They named the two additional quarks ''top'' ({{SubatomicParticle|Top quark}}) and ''bottom'' ({{SubatomicParticle|Bottom quark}}).<ref name="CERN" /> |

|||

[[Category:Baronetcies]] |

|||

It was the observation of the charm quark that finally convinced the physics community of the quark model's correctness.<ref name="Griffiths"/> Following a decade without empirical evidence supporting the flavor's existence, it was created and observed almost simultaneously by two teams in November 1974: one at the Stanford Linear Accelerator Center under [[Samuel C. C. Ting|Samuel Ting]] and one at [[Brookhaven National Laboratory]] under [[Burton Richter]]. The two parties had assigned the discovered particle two different names, J and ψ. The particle hence became formally known as the [[J/ψ meson]] and it was considered a quark–antiquark pair of the charm flavor that Glashow and Bjorken had predicted, or the [[Quarkonium|charmonium]].<ref name="Staley" /> |

|||

In 1977, the bottom quark was observed by [[Leon M. Lederman|Leon Lederman]] and a team at [[Fermilab]].<ref name="Carithers" /> This indicated that a top quark probably existed, because the bottom quark was without a partner. However, it was not until eighteen years later, in 1995, that the top quark was finally observed. The top quark's discovery was quite significant, because it proved to be far more massive than expected, almost as heavy as a [[gold]] atom. Reasons for the top quark's extremely large mass remain unclear.<ref name="BNLTop">{{cite web |title=New Precision Measurement of Top Quark Mass |publisher=[[Brookhaven National Laboratory]] News |url=http://www.bnl.gov/bnlweb/pubaf/pr/PR_display.asp?prID=04-66 |accessdate=2008-09-24}}</ref> |

|||

=== Etymology === |

|||

Gell-Mann originally named the quark after the sound ducks make.<ref>{{cite book |title=Richard Feynman: A Life in Science |author=J. Gribbin, M. Gribbin |publisher=[[Penguin Books]] |year=1997 |pages=p.194 |isbn=ISBN 0-452-27631-4}}</ref> For some time, Gell-Mann was undecided on an actual spelling for the term he had coined, until he found the word ''quark'' in [[James Joyce|James Joyce's]] book ''[[Finnegans Wake]]'': |

|||

{{epigraph|quote= |

|||

Three quarks for Muster Mark!<br /> |

|||

Sure he has not got much of a bark<br /> |

|||

And sure any he has it's all beside the mark. |

|||

|cite=James Joyce, ''Finnegans Wake'' <!--A reference with year of publication, chapter, ISBN, etc. would be useful.-->}} |

|||

Gell-Mann went into further detail regarding the name of the quark in his book, ''The Quark and the Jaguar: Adventures in the Simple and the Complex'', saying that the pronunciation for ''quark'' had been derived from ''quart'', which fitted perfectly with the three-quark theory in that one might have "three quarts of drinks at a bar."<ref name="Murray">{{cite book |author=M. Gell-Mann |title=The Quark and the Jaguar: Adventures in the Simple and the Complex |publisher=[[Owl Books]] |year=1995 |pages=p.180 |isbn=978-0805072532}}</ref> George Zweig, the co-proposer of the theory, preferred the name ''ace'' for the particle he had theorized, but Gell-Mann's terminology came to prominence once the quark model had been commonly accepted.<ref>{{cite book|last=Gleick|first=J.|title=Richard Feynman and modern physics|year=1992|publisher=[[Little Brown and Company]]|isbn=0-316-903167|pages=390}}</ref> |

|||

== Properties == |

|||

=== Flavor === |

|||

{{main|Flavor (physics)}} |

|||

Quarks come in six types, or "flavors".<ref>{{cite book |title=The Quantum World |author=K. W. Ford |publisher=[[Harvard University Press]] |year=2005 |pages=p.169 |isbn=067401832X }}</ref> This term has nothing to do with the typical human experience of [[flavor]], but is an arbitrarily named property that comes from a simple everyday word that is easy to comprehend and work with.<ref name="Knowing">{{cite book |title=Knowing |author=M. Munowitz |publisher=[[Oxford University Press]] (US) |year=2005 |isbn=0195167376 |pages=p.35}}</ref> |

|||

The six flavors are named ''up'', ''down'', ''charm'', ''strange'', ''top'' and ''bottom''; the top and bottom flavors are also known as ''truth'' and ''beauty'', respectively.<ref name="Kim">{{cite book |title=Elementary Particles and Their Interactions: Concepts and Phenomena |author=Q. Ho-Kim, X.-Y. Phạm |publisher=[[Springer Science+Business Media|Springer]] |year=1998 |pages=p.169 |isbn=3540636676}}</ref> Typically, only the stable up and down flavors are in common natural occurrence; heavier quarks can only be created in high-energy conditions, such as in [[cosmic ray]]s, and quickly decay into lighter quarks and other particles. Most studies conducted on heavier quarks have been performed in artificially-created conditions such as in [[particle accelerator]]s. |

|||

Flavors are grouped into three [[generation (particle physics)|generation]]s: the first generation comprises up and down quarks, the second comprises charm and strange, and the third comprises top and bottom. Quarks of higher generations have greater masses and thus are generally less stable than quarks of lower generations.<ref name="Knowing" /> Leptons are similarly divided into three generations. |

|||

For every quark flavor, there is a corresponding antiquark (denoted by the letter for the quark with an overbar, for example {{SubatomicParticle|Up antiquark}} for an up antiquark). Much like antimatter in general, antiquarks have the same mass and spin of their respective quarks, but the electric charge and other charges have the opposite sign.<ref>{{cite book |title=Zero to Infinity |author=P. Rowlands |pages=p.406 |publisher=[[World Scientific]] |year=2008 |isbn=9812709142}}</ref> Various quark flavor combinations result in the formation of composite particles known as [[hadron]]s. There are two types of hadrons: [[baryon]]s (made of three quarks) and [[meson]]s (made of a quark and an antiquark). The building blocks of the [[atomic nucleus]]—the [[proton]] and the [[neutron]]—are baryons.<ref name="Knowing" /> There are a great number of known hadrons, and most of them are differentiated by their quark content and the properties that these constituent quarks confer upon them.<ref name="Kim" /> |

|||

See the [[#Table of properties|table of properties below]] for a more complete analysis of the six quark flavors' properties. |

|||

==== Weak interaction ==== |

|||

{{main|Weak interaction}} |

|||

[[Image:Quarks and decays.png|thumb|right|250px|A pictorial representation of the six quarks' most likely 'decay' modes, with mass increasing from left to right. 'Decay' refers to the quantum process whereby one quantum particle transforms into one or more, other particles.]] |

|||

A quark of one flavor can transform, or decay, into a quark of a different flavor by the weak interaction. A quark can decay into a lighter quark by emitting a [[W and Z bosons|W boson]], or can absorb a W boson to turn into a heavier quark. This mechanism causes the [[radioactive decay|radioactive]] process known as [[beta decay]], in which a neutron "splits" into a proton, an electron and an [[antineutrino]]. This occurs when one of the down quarks in the neutron (composed by {{SubatomicParticle|up quark}}{{SubatomicParticle|down quark}}{{SubatomicParticle|down quark}}) decays into an up quark by emitting a {{SubatomicParticle|W boson-}} boson, transforming the neutron into a proton ({{SubatomicParticle|up quark}}{{SubatomicParticle|up quark}}{{SubatomicParticle|down quark}}). The {{SubatomicParticle|W boson-}} boson then decays into an electron ({{SubatomicParticle|Electron}}) and an electron antineutrino ({{SubatomicParticle|Electron antineutrino}}).<ref>{{cite web |title=Weak Interactions |url=http://www2.slac.stanford.edu/vvc/theory/weakinteract.html |accessdate = 2008-09-28 |year=2008 |work=Virtual Visitor Center |publisher=[[Stanford Linear Accelerator Center]] |location=Menlo Park, CA}}</ref> |

|||

=== Electric charge === |

|||

{{main|Electric charge}} |

|||

A quark has a fractional (i.e., ''non-integer'') charge value, either −1/3 or +2/3 (measured in [[elementary charge]]s); correspondingly, the charge of an antiquark can be either +1/3 or −2/3. The up, charm and top quarks all have charge of +2/3, while the down, strange and bottom quarks have −1/3. The electrical charge of a hadron is determined by the sum of the charges of the constituent quarks;<ref>{{cite book |title=Particles and Nuclei |year=2004 |author=B. Povh, K. Rith, C. Scholz, F. Zetsche, M. Lavelle |publisher=[[Springer Science+Business Media|Springer]] |isbn=3540201688 |oclc=53001447}}</ref>, but the total is always an [[integer]], even for the quark pairs that are detected in high-energy physics experiments. |

|||

[[Image:Quark structure proton.svg|thumb|right|The structure of the proton. With two up quarks, each with a charge of +2/3, and one down quark, with a charge of −1/3, the proton has a +1 charge.]] |

|||

The electric charge of quarks is important in the construction of nuclei. The hadron constituents of the atom, the neutron and proton, have charges of 0 and +1 respectively; the neutron is composed of two down quarks and one up quark, and the proton of two up quarks and one down quark. The total electric charge of a nucleus, that is, the number of protons in it, is known as the [[atomic number]], and it is the main difference between atoms of different [[chemical element]]s. Atoms usually have as many electrons as protons; since the electric charge of an electron is −1, the net electric charge of an atom is typically 0. When this is not the case, the atom is [[ionization|ionized]].<ref>{{cite book |author=W. Demtröder |year=2002 |title=Atoms, Molecules and Photons: An Introduction to Atomic- Molecular- and Quantum Physics |publisher=[[Springer Science+Business Media|Springer]] |edition=1st Edition |isbn=3540206310 |pages=39–42}}</ref> |

|||

=== Spin === |

|||

{{Main|Spin (physics)}} |

|||

The term ''spin'' denotes a property of physical particles corresponding to the rate and speed of a particle's rotation around its own axis. This concept is different in fundamental particles such as quarks, in that spin is an intrinsic property of point-like particles, rather than one derived from smaller components. The spin property is measured in units of ''h''/(2π), where ''h'' is the [[Planck constant]]. This unit is often denoted by ''ħ'', and called the "reduced Planck constant" or the Dirac constant. The component of the spin of a quark along any axis is always either ''ħ''/2 or its negative, −''ħ''/2; for this reason quarks are referred to as [[spin-½|spin-1/2]] particles, or fermions.<ref>{{cite book |title=The New Cosmic Onion |author=F. Close |pages=p.82 |publisher=[[CRC Press]] |year=2006 |isbn=1584887982}}</ref> |

|||

In quarks, spin notation uses up arrows ↑ and down arrows ↓, and general quark flavor notation. The flavor of the quark is first denoted using the first character of the flavor name, followed by either ↑ or ↓ to signify the values of +1/2 or −1/2, respectively. For example, an up quark with a positive spin of 1/2 along a given axis would be denoted u↑.<ref>{{cite book |title=Understanding the Universe |author=D. Lincoln |publisher=[[World Scientific]] |pages=p.116 |year=2004 |isbn=9812387056}}</ref> The quark's spin value contributes to the overall spin of the parent hadron, much as quark's electrical charge does to the overall charge of the hadron. Varying combinations of quark spins result in the total spin value that can be assigned to the hadron.<ref>{{cite web |title=Quarks |publisher=[[Antonine Education]] |url=http://www.antonine-education.co.uk/Physics_AS/Module_1/Topic_5/quarks.htm |accessdate=2008-07-10}}</ref> |

|||

=== Color === |

|||

{{main|Color charge}} |

|||

[[Image:Hadron colors.png|right|thumb|upright|All types of hadrons always have zero total color charge.]] |

|||

In addition to the electric charge, quarks carry another type of charge called ''color charge''. Despite its name, color charge is not related to color of visible light.<ref>{{cite book |title=Cosmology, Physics, and Philosophy |author=B. Gal-Or |publisher=[[Springer Science+Business Media|Springer]] |year=1983 |isbn=0387905812 |pages=p.276}}</ref> There are three types of color charge a quark can carry, named ''blue'', ''green'' and ''red''; each of them is complemented by an anti-color: ''antiblue'', ''antigreen'' and ''antired'', respectively. While a quark can have red, green or blue charge, an antiquark can have antired, antigreen, or antiblue charge. |

|||

The system of attraction and repulsion between quarks charged with any of the three colors (called [[strong interaction]], and described by [[quantum chromodynamics]]) is as follows: a quark charged with one color value will be attracted to an antiquark carrying with the corresponding anticolor, while three quarks all charged with differing colors will similarly be forced together. In any other case, a force of repulsion will come into effect.<ref>{{cite book |title=The Moment of Creation |author=J. S. Trefil, G. Walters |pages=p.112 |publisher=[[Courier Dover Publications]] |year=2004 |isbn=0486438139}}</ref> Quarks initiate these color interactions via the exchange of a particle known as a [[gluon]], a concept which is [[#Color confinement and gluons|discussed below]]. |

|||

It is when the process of [[hadronization]] occurs that the three color types become relevant. The products of both instances of attraction will be color neutrality; a quark with ''n'' charge plus an antiquark of −''n'' charge will result in a color charge of 0, or "white". The combination of all three color charge types will similarly result in a canceling out of all color, yielding the same white color type as the interaction between the quark and antiquark. These two methods of color neutral hadronization represent the same ways the two types of hadrons are formed (hadrons must be color neutral); a meson, comprised of two particles, is the result of the binding of a quark and antiquark color charged oppositely, while a baryon, containing three particles, arises from the hadronization of three quarks all charged with different colors.<ref>{{cite book |title=Deep Down Things |author=B. A. Schumm |pages=p.131–132 |publisher=[[JHU Press]] |year=2004 |isbn=080187971X |oclc=55229065}}</ref> |

|||

=== Mass === |

|||

There are two different terms used when describing a quark's mass; ''current quark mass'' refers to the mass of a quark by itself, while ''constituent quark mass'' refers to the current quark mass plus the mass of the gluon particle field surrounding the quark.<ref>{{cite book |title=The Quantum Quark |author=A. Watson |pages=p.286 |publisher=[[Cambridge University Press]] |year=2004 |isbn=0521829070}}</ref> These two values are typically very different in their relative size, for several reasons. |

|||

In a hadron most of the mass comes from the gluons that bind the constituent quarks together, rather than from the individual quarks; the mass of the quarks is almost negligible compared to the mass derived from the gluons' energy. While gluons are inherently massless, they possess energy, and it is this energy that contributes so greatly to the overall mass of the hadron. This is demonstrated by a common hadron–the proton. Composed of one {{SubatomicParticle|down quark}} and two {{SubatomicParticle|up quark}} quarks, the proton has an overall mass of approximately 938 [[Electron volt#As a unit of mass|MeV/c<sup>2</sup>]], of which the three quarks contribute around 15 MeV/c<sup>2</sup>, the remainder is from the energy of the gluons.<ref name="Veltman" /><ref>{{cite book |title=Quarks and Nuclei |author=W. Weise, A. M. Green |pages=p.65 |publisher=[[World Scientific]] |year=1984 |isbn=9971966611}}</ref> |

|||

This makes the calculation of quark mass difficult. Often, mass values can be derived after calculating the difference in mass between two related hadrons that have opposing or complementary quark components; for example, the proton to the neutron, where the difference between the two is one down quark to one up quark, the relative masses and the mass differences of which can then be measured by the difference in the overall mass of the two hadrons.<ref name="Veltman" /> |

|||

The masses of most quarks were within predicted ranges at the time of their discovery, with the notable exception of the top quark, which was found to have a mass approximately equal to that of a [[gold]] [[atomic nucleus|nucleus]], around 200 times heavier than the hadron it was thought to form.<ref>{{cite web|title=The Top Quark: Worth its Weight in Gold |author=F. Canelli |url=http://conferences.fnal.gov/lp2003/forthepublic/topquark/index.html |publisher=[[University of Rochester]] |accessdate=2008-10-24}}</ref> Various theories have been offered to explain this very large mass; common predictions assert that the answer to the abnormality will be found when more is known about the top quark's interaction with the Higgs field, and how the [[Higgs boson]] produces mass and makes mass possible.<ref name="BNLTop" /> |

|||

=== Table of properties === |

|||

The following table summarizes the key properties of the six known quarks: |

|||

{| class="wikitable sortable" style="margin: 0 auto; text-align:center" |

|||

|+'''Quark flavor properties'''<ref>C. Amsler et al. (Particle Data Group), PL '''B667''', 1 (2008) (URL: http://pdg.lbl.gov/2008/tables/rpp2008-sum-quarks.pdf)</ref> |

|||

! Name |

|||

! Symbol |

|||

! Generation |

|||

! Mass ([[electronvolt|MeV]]/[[speed of light|c]]<sup>2</sup>) |

|||

! Spin |

|||

! Electric charge |

|||

! Antiparticle |

|||

! Antiparticle symbol |

|||

|- |

|||

|style="background:#fcc;"| Up |

|||

|style="background:#fcc;"| {{SubatomicParticle|Up quark}} |

|||

|style="background:#cff;"| 1 |

|||

| <span style="display: none;">000001.5</span>1.5 to 3.3 |

|||

| 1/2 |

|||

|style="background:#fff;"| +2/3 |

|||

|style="background:#fcc;"| Antiup |

|||

|style="background:#fcc;"| {{SubatomicParticle|Up antiquark}} |

|||

|- |

|||

|style="background:#ccf;"| Down |

|||

|style="background:#ccf;"| {{SubatomicParticle|Down quark}} |

|||

|style="background:#cff;"| 1 |

|||

| <span style="display: none;">000003.5</span>3.5 to 6.0 |

|||

| 1/2 |

|||

|style="background:#ccc;"| −1/3 |

|||

|style="background:#ccf;"| Antidown |

|||

|style="background:#ccf;"| {{SubatomicParticle|Down antiquark}} |

|||

|- |

|||

|style="background:#f9f;"| Charm |

|||

|style="background:#f9f;"| {{SubatomicParticle|Charm quark}} |

|||

|style="background:#9cf;"| 2 |

|||

| <span style="display: none;">001160.0</span>1160 to 1340 |

|||

| 1/2 |

|||

|style="background:#fff;"| +2/3 |

|||

|style="background:#f9f;"| Anticharm |

|||

|style="background:#f9f;"| {{SubatomicParticle|Charm antiquark}} |

|||

|- |

|||

|style="background:#ff9;"| Strange |

|||

|style="background:#ff9;"| {{SubatomicParticle|Strange quark}} |

|||

|style="background:#9cf;"| 2 |

|||

| <span style="display: none;">000070.0</span>70 to 130 |

|||

| 1/2 |

|||

|style="background:#ccc;"| −1/3 |

|||

|style="background:#ff9;"| Antistrange |

|||

|style="background:#ff9;"| {{SubatomicParticle|Strange antiquark}} |

|||

|- |

|||

|style="background:#cfc;"| Top |

|||

|style="background:#cfc;"| {{SubatomicParticle|Top quark}} |

|||

|style="background:#69f;"| 3 |

|||

| <span style="display: none;">169100.0</span>169,100 to 173,300 |

|||

| 1/2 |

|||

|style="background:#fff;"| +2/3 |

|||

|style="background:#cfc;"| Antitop |

|||

|style="background:#cfc;"| {{SubatomicParticle|Top antiquark}} |

|||

|- |

|||

|style="background:#fc9;"| Bottom |

|||

|style="background:#fc9;"| {{SubatomicParticle|Bottom quark}} |

|||

|style="background:#69f;"| 3 |

|||

| <span style="display: none;">004130.0</span>4130 to 4370 |

|||

| 1/2 |

|||

|style="background:#ccc;"| −1/3 |

|||

|style="background:#fc9;"| Antibottom |

|||

|style="background:#fc9;"| {{SubatomicParticle|Bottom antiquark}} |

|||

|} |

|||

== Color confinement and gluons == |

|||

A phenomenon called ''color confinement'' comes into effect within hadrons. This refers to a quark's inability to be separated from its hadron, therefore rendering isolated observation impossible. This makes direct observation impossible for all quarks except the top; instead, what is known about quarks has been inferred from the effect they have on their parent hadron's properties.<ref>{{cite book|title=Relativistic quantum mechanics and quantum fields|author=T. Wu, W.-Y. Pauchy Hwang |pages=p. 321 |publisher=[[World Science]] |year=1991 |isbn=9810206089}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |title=100 Years Werner Heisenberg: Works and Impact |last=D. Papenfuss, D. Lüst, W. Schleich |year=2002 |publisher=[[Wiley-VCH]] |isbn=3527403922 |oclc=50694495}}</ref> The top quark is an exception because its lifetime is so short that it does not have a chance to hadronize.<ref name=Garberson>{{cite conference|title=Top Quark Mass and Cross Section Results from the Tevatron|author=F. Garberson |conference= Hadron Collider Physics Symposium (HCP2008), Galena, Illinois, USA |year=2008|url= http://arxiv.org/abs/0808.0273}}</ref> One method used is comparing two hadrons that have all but one quark in common, the properties of the different quark are inferred from the difference in values between the two hadrons. Color confinement is primarily caused by interactions with particles known as [[gluons]]. |

|||

Quarks have an inherent relationship with the gluon, which is technically a massless [[vector field|vector]] [[gauge boson]]. Gluons are responsible for the color field, or the [[strong interaction]], that ensures that quarks remain bound in hadrons and instigates color confinement, and are the subjects of the [[quantum chromodynamics]] research area.<ref>{{cite book |title=Electroweak Interactions |author=P. Renton |publisher=[[Cambridge University Press]] |year=1988 |isbn=0521366925 |pages=332}}</ref> Gluons, roughly speaking, carry both a color charge and an anti-color charge, for example red–antiblue.<ref>{{cite book |title=Astroparticle Physics|author=C. Grupen, G. Cowan, S. D. Eidelman, T. Stroh |publisher=[[Springer Science+Business Media|Springer]] |year=2005 |pages=p.26 |isbn=3540253122}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |title=Why are there eight gluons and not nine? |author=J. Bottomley, [[John Baez|J. Baez]] |url=http://math.ucr.edu/home/baez/physics/ParticleAndNuclear/gluons.html |accessdate=2008-09-28 |year=1996 |work=Usenet Physics FAQ}}</ref> |

|||

Gluons are constantly exchanged between quarks through an emission and reception process. These gluon exchange events between quarks are extremely frequent, occurring approximately 10<sup>24</sup> times every second.<ref>{{cite book |title=World in Process |author=J. A. Jungerman |publisher=[[SUNY Press]] |year=2000 |pages=p.107 |isbn=0791447499}}</ref> When a gluon is transferred between one quark and another, a color change comes into effect in the receiving and emitting quark.<ref name="Veltman">{{cite book |title=Facts and Mysteries in Elementary Particle Physics |author=M. Veltman |publisher=[[World Scientific]] |year=2003 |pages=p.46 |isbn=981238149X}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |title=Fantastic Realities |author=F. Wilczek, B. Devine |pages=p.85 |publisher=[[World Scientific]] |year=2006 |isbn=981256649X}}</ref> These constant switches in color within quarks are mediated by the gluons in such a way that a bound hadron will constantly retain a dynamic and ever-changing set of color types that will preserve the force of attraction, therefore forever disallowing quarks to exist in isolation.<ref name="Webb">{{cite book |title=Out of this World |author=S. Webb |publisher=[[Springer Science+Business Media|Springer]] |year=2004 |isbn=0387029303 |pages=p.91}}</ref> |

|||

The color field the gluon creates is structured with a mechanism that contributes to a hadron's indivisibility. This is demonstrated by the varying strength of the binding force between the constituent quarks of a hadron; as quarks come closer to each other, the binding force actually weakens (this is called [[asymptotic freedom]]), but while they drift further apart, the strength of the bind dramatically increases. This is because as the color field is stressed by the drifting away of a quark, much as an elastic band is stressed when pulled apart, a proportionate and necessary multitude of gluons of appropriate color property are created to strengthen the stretched field. In this way, an infinite amount of energy would be required to wrench a quark from its hadronized state.<ref>{{cite book |title=Origin |author=T.Yulsman |publisher=[[CRC Press]] |year=2002 |isbn=075030765X|pages=55}}</ref> |

|||

These strong interactions are [[Nonlinear system|non-linear]], because gluons can emit gluons and exchange gluons with other gluons. This property has led to postulations regarding the possible existence of a particle that is purely gluon—a [[glueball]]—despite previous observations indicating that gluons cannot exist without attached quarks.<ref>{{cite book |title='96 Electroweak Interactions and Unified Theories |author=J. T. V Tran |pages=p.60 |publisher=[[Atlantica Séguier Frontières]] |year=1996 |isbn=2863322052}}</ref> |

|||

=== Sea quarks === |

|||

Those quarks that make up the core of the hadron are called ''valence quarks''. These quarks are generally stable, and are the quarks that contribute to the [[quantum number]]s of their hadrons. However, from the gluons' strong interaction field are born short-lived, [[virtual particle|virtual]] quark–antiquark ({{SubatomicParticle|quark}}{{SubatomicParticle|antiquark}}) pairs, known as ''sea quarks''. These sea quarks are much less stable, and they annihilate each other very quickly within the interior of the hadron. They are born from the splitting of a gluon, but when the sea quark is annihilated, new gluons are produced.<ref>{{cite book |title=Learning about Particles |author=J. Steinberger |publisher=[[Springer Science+Business Media|Springer]] |year=2005 |isbn=3540213295 |pages=p.130}}</ref> There is a constant quantum flux of sea quarks that are born from the vacuum, and this allows for a constant cycle of gluon splits and rebirths. This flux is colloquially known as "the sea".<ref>{{cite book|title=Elementary-particle Physics|author=National Research Council (U.S.). Elementary-Particle Physics Panel|pages=62|publisher=[[National Academies Press]]|year=1986|isbn=0309035767}}</ref> |

|||

== References == |

|||

{{reflist|2}} |

|||

== Further reading == |

|||

*{{cite book |authorlink= David Griffiths (physicist)|author= D. J. Griffiths |title=Introduction to Elementary Particles |publisher=[[John Wiley & Sons]] |year=1987 |isbn=0-471-60386-4 }} |

|||

*{{cite book |authorlink= Andrew Pickering|author= A. Pickering |title=Constructing Quarks: A Sociological History of Particle Physics |publisher=[[The University of Chicago Press]] |year=1984 |isbn=0-226-66799-5 }} |

|||

*{{cite book |author= B. Povh |title=Particles and Nuclei: An Introduction to the Physical Concepts |publisher=[[Springer-Verlag]] |year=1995 |isbn=0-387-59439-6}} |

|||

== External links == |

|||

{{Commons|Quark}} |

|||

*[http://books.nap.edu/books/0309048931/html/245.html A Positron Named Priscilla] – A description of [[CERN|CERN’s]] experiment to count the families of quarks. |

|||

*[http://www.scribd.com/word/view/1025 An elementary popular introduction] |

|||

*[http://pdg.lbl.gov/quarkdance/ Quark dance] |

|||

*[http://www.bartleby.com/61/67/Q0016700.html The original English word ''quark'' and its adaptation to particle physics] |

|||

{{Particles}} |

|||

[[Category:Quarks|Quark]] |

|||

[[Category:Fundamental physics concepts|Quark]] |

|||

<!-- Interlanguage links --> |

|||

[[ar:كوارك]] |

|||

[[ast:Quark]] |

|||

[[bn:কোয়ার্ক]] |

|||

[[bs:Kvark]] |

|||

[[bg:Кварк]] |

|||

[[ca:Quark]] |

|||

[[cs:Kvark]] |

|||

[[da:Kvark (fysik)]] |

|||

[[de:Quark (Physik)]] |

|||

[[et:Kvargid]] |

|||

[[el:Κουάρκ]] |

|||

[[es:Quark]] |

|||

[[eo:Kvarko]] |

|||

[[fa:کوارک]] |

|||

[[fr:Quark]] |

|||

[[ga:Cuarc]] |

|||

[[gl:Quark]] |

|||

[[ko:쿼크]] |

|||

[[hr:Kvark]] |

|||

[[id:Quark]] |

|||

[[is:Kvarki]] |

|||

[[it:Quark (particella)]] |

|||

[[he:קווארק]] |

|||

[[ku:Kuark]] |

|||

[[la:Quarcum]] |

|||

[[lv:Kvarki]] |

|||

[[lt:Kvarkas]] |

|||

[[hu:Kvark]] |

|||

[[mk:Кварк]] |

|||

[[ml:ക്വാര്ക്ക്]] |

|||

[[ms:Kuark]] |

|||

[[nl:Quark]] |

|||

[[ja:クォーク]] |

|||

[[no:Kvark]] |

|||

[[nn:Kvark]] |

|||

[[uz:Kvark]] |

|||

[[pl:Kwark]] |

|||

[[pt:Quark]] |

|||

[[ro:Quark]] |

|||

[[ru:Кварк]] |

|||

[[simple:Quark]] |

|||

[[sk:Kvark]] |

|||

[[sl:Kvark]] |

|||

[[sr:Кварк]] |

|||

[[sh:Kvark]] |

|||

[[fi:Kvarkki]] |

|||

[[sv:Kvark]] |

|||

[[ta:குவார்க்]] |

|||

[[vi:Quark]] |

|||

[[tr:Kuark]] |

|||

[[uk:Кварк]] |

|||

[[ur:کوارک]] |

|||

[[zh:夸克]] |

|||

Revision as of 14:30, 11 October 2008

In physics, a quark (/kwɔrk/, /kwɑːk/ or /kwɑːrk/) is a type of subatomic particle.[1] Quarks are elementary fermionic particles which strongly interact due to their color charge.[2] Due to the phenomenon of color confinement, quarks are never found on their own: they are always bound together in composite particles named hadrons.[3] The most common hadrons are the proton and the neutron, which are the components of atomic nuclei.

There are six different types of quarks, known as flavors: up (symbol:

u

), down (

d

), charm (

c

), strange (

s

), top (

t

), and bottom (

b

).[4]

The lightest flavors, the up quark and the down quark, are generally stable and are very common in the universe as they are the constituents of protons and neutrons. The more massive charm, strange, top and bottom quarks are unstable and rapidly decay; these can only be produced as quark-pairs under high energy conditions, such as in particle accelerators and in cosmic rays. For every quark flavor there is an antiparticle, called an antiquark, that differs from quarks only in that some of their properties have the opposite sign.

The quark model was independently proposed by physicists Murray Gell-Mann and George Zweig in 1964.[5] There was little evidence for the theory until 1968, when electron-proton scattering experiments indicated the existence of substructure within the proton resembling three 'sphere-like' regions within the proton.[6][7] By 1995, when the top quark was observed at Fermilab, all the six flavors had been observed. Since quarks are not found in isolation, their properties can only be deduced from experiments on hadrons.[3] An exception to this rule is the top quark, which decays so rapidly that it does not produce hadrons at all, and instead is observed through the identification of the particles it has decayed into.[8]

History

The quark theory was first postulated by physicists Murray Gell-Mann and George Zweig in 1964.[5] At the time of the theory's initial proposal, the "particle zoo" consisted of several leptons and many different hadrons. Gell-Mann and Zweig developed the quark theory to explain the hadrons; they proposed that various combinations of quarks and antiquarks were the components of the hadrons, which were at the time considered to be indivisible.[9]

The Gell-Mann–Zweig model predicted three quarks, which they named up, down and strange (

u

,

d

,

s

). At the time, the pair of physicists ascribed various properties and values to the three new proposed particles, such as electric charge and spin.[10] The initial reaction of the physics community to the proposal was mixed, many having reservations regarding the actual physicality of the quark concept. They believed the quark was merely an abstract concept that could be used temporarily to help explain certain concepts that were not well understood, rather than an actual entity that existed in the way that Gell-Mann and Zweig had envisioned.[9]

In less than a year, extensions to the Gell-Mann–Zweig model were proposed when another duo of physicists, Sheldon Lee Glashow and James Bjorken, predicted the existence of a fourth flavor of quark, which they referred to as charm (

c

). The addition was proposed because it expanded the power and self consistency of the theory: it allowed a better description of the weak interaction (the mechanism that allows quarks to decay); equalized the number of quarks with the number of known leptons; and implied a mass formula that correctly reproduced the masses of the known mesons.[11]

In 1968, deep inelastic scattering experiments at the Stanford Linear Accelerator Center showed that the proton had substructure.[12][6][7] However, whilst the concept of hadron substructure had been proven, there was still apprehension towards the quark model: the substructures became known at the time as partons, (a term proposed by Nobel Laureate Richard Feynman, and supported by some experimental project reports[13],[14]), but it "was unfashionable to identify them explicitly with quarks".[15] These partons were later identified as up and down quarks.[16] Their discovery also validated the existence of a third strange quark, because it was necessary to the model Gell-Mann and Zweig had proposed.[17]

In a 1970 paper,[18] Glashow, John Iliopoulos, and Luciano Maiani gave more compelling theoretical arguments for the as-yet undiscovered charm quark.[19] The number of proposed quark flavors grew to the current six in 1973, when Makoto Kobayashi and Toshihide Maskawa noted that the experimental observation of CP violation could be explained if there were another pair of quarks. They named the two additional quarks top (

t

) and bottom (

b

).[10]

It was the observation of the charm quark that finally convinced the physics community of the quark model's correctness.[15] Following a decade without empirical evidence supporting the flavor's existence, it was created and observed almost simultaneously by two teams in November 1974: one at the Stanford Linear Accelerator Center under Samuel Ting and one at Brookhaven National Laboratory under Burton Richter. The two parties had assigned the discovered particle two different names, J and ψ. The particle hence became formally known as the J/ψ meson and it was considered a quark–antiquark pair of the charm flavor that Glashow and Bjorken had predicted, or the charmonium.[9]

In 1977, the bottom quark was observed by Leon Lederman and a team at Fermilab.[5] This indicated that a top quark probably existed, because the bottom quark was without a partner. However, it was not until eighteen years later, in 1995, that the top quark was finally observed. The top quark's discovery was quite significant, because it proved to be far more massive than expected, almost as heavy as a gold atom. Reasons for the top quark's extremely large mass remain unclear.[20]

Etymology

Gell-Mann originally named the quark after the sound ducks make.[21] For some time, Gell-Mann was undecided on an actual spelling for the term he had coined, until he found the word quark in James Joyce's book Finnegans Wake:

Three quarks for Muster Mark!

Sure he has not got much of a bark

And sure any he has it's all beside the mark.

— James Joyce, Finnegans Wake

Gell-Mann went into further detail regarding the name of the quark in his book, The Quark and the Jaguar: Adventures in the Simple and the Complex, saying that the pronunciation for quark had been derived from quart, which fitted perfectly with the three-quark theory in that one might have "three quarts of drinks at a bar."[22] George Zweig, the co-proposer of the theory, preferred the name ace for the particle he had theorized, but Gell-Mann's terminology came to prominence once the quark model had been commonly accepted.[23]

Properties

Flavor

Quarks come in six types, or "flavors".[24] This term has nothing to do with the typical human experience of flavor, but is an arbitrarily named property that comes from a simple everyday word that is easy to comprehend and work with.[25]

The six flavors are named up, down, charm, strange, top and bottom; the top and bottom flavors are also known as truth and beauty, respectively.[3] Typically, only the stable up and down flavors are in common natural occurrence; heavier quarks can only be created in high-energy conditions, such as in cosmic rays, and quickly decay into lighter quarks and other particles. Most studies conducted on heavier quarks have been performed in artificially-created conditions such as in particle accelerators.

Flavors are grouped into three generations: the first generation comprises up and down quarks, the second comprises charm and strange, and the third comprises top and bottom. Quarks of higher generations have greater masses and thus are generally less stable than quarks of lower generations.[25] Leptons are similarly divided into three generations.

For every quark flavor, there is a corresponding antiquark (denoted by the letter for the quark with an overbar, for example

u

for an up antiquark). Much like antimatter in general, antiquarks have the same mass and spin of their respective quarks, but the electric charge and other charges have the opposite sign.[26] Various quark flavor combinations result in the formation of composite particles known as hadrons. There are two types of hadrons: baryons (made of three quarks) and mesons (made of a quark and an antiquark). The building blocks of the atomic nucleus—the proton and the neutron—are baryons.[25] There are a great number of known hadrons, and most of them are differentiated by their quark content and the properties that these constituent quarks confer upon them.[3]

See the table of properties below for a more complete analysis of the six quark flavors' properties.

Weak interaction

A quark of one flavor can transform, or decay, into a quark of a different flavor by the weak interaction. A quark can decay into a lighter quark by emitting a W boson, or can absorb a W boson to turn into a heavier quark. This mechanism causes the radioactive process known as beta decay, in which a neutron "splits" into a proton, an electron and an antineutrino. This occurs when one of the down quarks in the neutron (composed by

u

d

d

) decays into an up quark by emitting a

W−

boson, transforming the neutron into a proton (

u

u

d

). The

W−

boson then decays into an electron (

e−

) and an electron antineutrino (

ν

e).[27]

Electric charge

A quark has a fractional (i.e., non-integer) charge value, either −1/3 or +2/3 (measured in elementary charges); correspondingly, the charge of an antiquark can be either +1/3 or −2/3. The up, charm and top quarks all have charge of +2/3, while the down, strange and bottom quarks have −1/3. The electrical charge of a hadron is determined by the sum of the charges of the constituent quarks;[28], but the total is always an integer, even for the quark pairs that are detected in high-energy physics experiments.

The electric charge of quarks is important in the construction of nuclei. The hadron constituents of the atom, the neutron and proton, have charges of 0 and +1 respectively; the neutron is composed of two down quarks and one up quark, and the proton of two up quarks and one down quark. The total electric charge of a nucleus, that is, the number of protons in it, is known as the atomic number, and it is the main difference between atoms of different chemical elements. Atoms usually have as many electrons as protons; since the electric charge of an electron is −1, the net electric charge of an atom is typically 0. When this is not the case, the atom is ionized.[29]

Spin

The term spin denotes a property of physical particles corresponding to the rate and speed of a particle's rotation around its own axis. This concept is different in fundamental particles such as quarks, in that spin is an intrinsic property of point-like particles, rather than one derived from smaller components. The spin property is measured in units of h/(2π), where h is the Planck constant. This unit is often denoted by ħ, and called the "reduced Planck constant" or the Dirac constant. The component of the spin of a quark along any axis is always either ħ/2 or its negative, −ħ/2; for this reason quarks are referred to as spin-1/2 particles, or fermions.[30]

In quarks, spin notation uses up arrows ↑ and down arrows ↓, and general quark flavor notation. The flavor of the quark is first denoted using the first character of the flavor name, followed by either ↑ or ↓ to signify the values of +1/2 or −1/2, respectively. For example, an up quark with a positive spin of 1/2 along a given axis would be denoted u↑.[31] The quark's spin value contributes to the overall spin of the parent hadron, much as quark's electrical charge does to the overall charge of the hadron. Varying combinations of quark spins result in the total spin value that can be assigned to the hadron.[32]

Color

In addition to the electric charge, quarks carry another type of charge called color charge. Despite its name, color charge is not related to color of visible light.[33] There are three types of color charge a quark can carry, named blue, green and red; each of them is complemented by an anti-color: antiblue, antigreen and antired, respectively. While a quark can have red, green or blue charge, an antiquark can have antired, antigreen, or antiblue charge.

The system of attraction and repulsion between quarks charged with any of the three colors (called strong interaction, and described by quantum chromodynamics) is as follows: a quark charged with one color value will be attracted to an antiquark carrying with the corresponding anticolor, while three quarks all charged with differing colors will similarly be forced together. In any other case, a force of repulsion will come into effect.[34] Quarks initiate these color interactions via the exchange of a particle known as a gluon, a concept which is discussed below.

It is when the process of hadronization occurs that the three color types become relevant. The products of both instances of attraction will be color neutrality; a quark with n charge plus an antiquark of −n charge will result in a color charge of 0, or "white". The combination of all three color charge types will similarly result in a canceling out of all color, yielding the same white color type as the interaction between the quark and antiquark. These two methods of color neutral hadronization represent the same ways the two types of hadrons are formed (hadrons must be color neutral); a meson, comprised of two particles, is the result of the binding of a quark and antiquark color charged oppositely, while a baryon, containing three particles, arises from the hadronization of three quarks all charged with different colors.[35]

Mass

There are two different terms used when describing a quark's mass; current quark mass refers to the mass of a quark by itself, while constituent quark mass refers to the current quark mass plus the mass of the gluon particle field surrounding the quark.[36] These two values are typically very different in their relative size, for several reasons.

In a hadron most of the mass comes from the gluons that bind the constituent quarks together, rather than from the individual quarks; the mass of the quarks is almost negligible compared to the mass derived from the gluons' energy. While gluons are inherently massless, they possess energy, and it is this energy that contributes so greatly to the overall mass of the hadron. This is demonstrated by a common hadron–the proton. Composed of one

d

and two

u

quarks, the proton has an overall mass of approximately 938 MeV/c2, of which the three quarks contribute around 15 MeV/c2, the remainder is from the energy of the gluons.[37][38]

This makes the calculation of quark mass difficult. Often, mass values can be derived after calculating the difference in mass between two related hadrons that have opposing or complementary quark components; for example, the proton to the neutron, where the difference between the two is one down quark to one up quark, the relative masses and the mass differences of which can then be measured by the difference in the overall mass of the two hadrons.[37]

The masses of most quarks were within predicted ranges at the time of their discovery, with the notable exception of the top quark, which was found to have a mass approximately equal to that of a gold nucleus, around 200 times heavier than the hadron it was thought to form.[39] Various theories have been offered to explain this very large mass; common predictions assert that the answer to the abnormality will be found when more is known about the top quark's interaction with the Higgs field, and how the Higgs boson produces mass and makes mass possible.[20]

Table of properties

The following table summarizes the key properties of the six known quarks:

| Name | Symbol | Generation | Mass (MeV/c2) | Spin | Electric charge | Antiparticle | Antiparticle symbol |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Up | u |

1 | 1.5 to 3.3 | 1/2 | +2/3 | Antiup | u |

| Down | d |

1 | 3.5 to 6.0 | 1/2 | −1/3 | Antidown | d |

| Charm | c |

2 | 1160 to 1340 | 1/2 | +2/3 | Anticharm | c |

| Strange | s |

2 | 70 to 130 | 1/2 | −1/3 | Antistrange | s |

| Top | t |

3 | 169,100 to 173,300 | 1/2 | +2/3 | Antitop | t |

| Bottom | b |

3 | 4130 to 4370 | 1/2 | −1/3 | Antibottom | b |

Color confinement and gluons

A phenomenon called color confinement comes into effect within hadrons. This refers to a quark's inability to be separated from its hadron, therefore rendering isolated observation impossible. This makes direct observation impossible for all quarks except the top; instead, what is known about quarks has been inferred from the effect they have on their parent hadron's properties.[41][42] The top quark is an exception because its lifetime is so short that it does not have a chance to hadronize.[8] One method used is comparing two hadrons that have all but one quark in common, the properties of the different quark are inferred from the difference in values between the two hadrons. Color confinement is primarily caused by interactions with particles known as gluons.

Quarks have an inherent relationship with the gluon, which is technically a massless vector gauge boson. Gluons are responsible for the color field, or the strong interaction, that ensures that quarks remain bound in hadrons and instigates color confinement, and are the subjects of the quantum chromodynamics research area.[43] Gluons, roughly speaking, carry both a color charge and an anti-color charge, for example red–antiblue.[44][45]

Gluons are constantly exchanged between quarks through an emission and reception process. These gluon exchange events between quarks are extremely frequent, occurring approximately 1024 times every second.[46] When a gluon is transferred between one quark and another, a color change comes into effect in the receiving and emitting quark.[37][47] These constant switches in color within quarks are mediated by the gluons in such a way that a bound hadron will constantly retain a dynamic and ever-changing set of color types that will preserve the force of attraction, therefore forever disallowing quarks to exist in isolation.[48]

The color field the gluon creates is structured with a mechanism that contributes to a hadron's indivisibility. This is demonstrated by the varying strength of the binding force between the constituent quarks of a hadron; as quarks come closer to each other, the binding force actually weakens (this is called asymptotic freedom), but while they drift further apart, the strength of the bind dramatically increases. This is because as the color field is stressed by the drifting away of a quark, much as an elastic band is stressed when pulled apart, a proportionate and necessary multitude of gluons of appropriate color property are created to strengthen the stretched field. In this way, an infinite amount of energy would be required to wrench a quark from its hadronized state.[49]

These strong interactions are non-linear, because gluons can emit gluons and exchange gluons with other gluons. This property has led to postulations regarding the possible existence of a particle that is purely gluon—a glueball—despite previous observations indicating that gluons cannot exist without attached quarks.[50]

Sea quarks

Those quarks that make up the core of the hadron are called valence quarks. These quarks are generally stable, and are the quarks that contribute to the quantum numbers of their hadrons. However, from the gluons' strong interaction field are born short-lived, virtual quark–antiquark (

q

q

) pairs, known as sea quarks. These sea quarks are much less stable, and they annihilate each other very quickly within the interior of the hadron. They are born from the splitting of a gluon, but when the sea quark is annihilated, new gluons are produced.[51] There is a constant quantum flux of sea quarks that are born from the vacuum, and this allows for a constant cycle of gluon splits and rebirths. This flux is colloquially known as "the sea".[52]

References

- ^ "Fundamental Particles". Oxford Physics. Retrieved 2008-06-29.

- ^ "Quark (subatomic particle)". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2008-06-29.

- ^ a b c d Q. Ho-Kim, X.-Y. Phạm (1998). Elementary Particles and Their Interactions: Concepts and Phenomena. Springer. pp. p.169. ISBN 3540636676.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ "Quarks". HyperPhysics. Retrieved 2008-06-29.

- ^ a b c B. Carithers, P. Grannis. "Discovery of the Top Quark" (PDF). Retrieved 2008-09-23.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b E. D. Bloom (1969). "High-Energy Inelastic e-p Scattering at 6° and 10°". Physical Review Letters. 23: p.930. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.23.930.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ a b M. Breidenbach (1969). "Observed Behavior of Highly Inelastic Electron-Proton Scattering". Physical Review Letters. 23: p.935. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.23.935.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ a b F. Garberson (2008). Top Quark Mass and Cross Section Results from the Tevatron. Hadron Collider Physics Symposium (HCP2008), Galena, Illinois, USA.

- ^ a b c K.W. Staley (2004). The Evidence for the Top Quark. Cambridge University Press. pp. p.15. ISBN 0521827108.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ a b "Funny Quarks". CERN. Retrieved 2008-09-24.

- ^ B. J. Bjorken, S. L. Glashow (1964). "Elementary Particles and SU(4)". Physics Letters. 11: p.255. doi:10.1016/0031-9163(64)90433-0.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ J.I. Friedman. "The Road to the Nobel Prize". Hue University. Retrieved 2008-09-29.

- ^ Richard P. Feynman, Proceedings of the 3rd Topical Conference on High Energy Collision of Hadrons, Stony Brook, N. Y. (1969)

- ^ CTEQ Collaboration, S. Kretzer et al., "CTEQ6 Parton Distributions with Heavy Quark Mass Effects", Phys. Rev. D69, 114005 (2004).

- ^ a b D. J. Griffiths (1987). Introduction to Elementary Particles. John Wiley & Sons. pp. p.42. ISBN 0-471-60386-4.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ L. M. Lederman, D. Teresi (2006). The God Particle. Mariner Books. pp. p.208. ISBN 0618711686.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ Schombert, James. "Short History of Particles". University of Oregon. Retrieved 5 October.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ S. L. Glashow, J. Iliopoulos, L. Maiani (1970). "Weak Interactions with Lepton-Hadron Symmetry". Physical Review D. 2: 1285. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.2.1285. Retrieved 2008-09-29.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ D. J. Griffiths (1987). Introduction to Elementary Particles. John Wiley & Sons. pp. p.44. ISBN 0-471-60386-4.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ a b "New Precision Measurement of Top Quark Mass". Brookhaven National Laboratory News. Retrieved 2008-09-24.

- ^ J. Gribbin, M. Gribbin (1997). Richard Feynman: A Life in Science. Penguin Books. pp. p.194. ISBN ISBN 0-452-27631-4.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - ^ M. Gell-Mann (1995). The Quark and the Jaguar: Adventures in the Simple and the Complex. Owl Books. pp. p.180. ISBN 978-0805072532.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ Gleick, J. (1992). Richard Feynman and modern physics. Little Brown and Company. p. 390. ISBN 0-316-903167.

- ^ K. W. Ford (2005). The Quantum World. Harvard University Press. pp. p.169. ISBN 067401832X.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ a b c M. Munowitz (2005). Knowing. Oxford University Press (US). pp. p.35. ISBN 0195167376.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ P. Rowlands (2008). Zero to Infinity. World Scientific. pp. p.406. ISBN 9812709142.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ "Weak Interactions". Virtual Visitor Center. Menlo Park, CA: Stanford Linear Accelerator Center. 2008. Retrieved 2008-09-28.

- ^ B. Povh, K. Rith, C. Scholz, F. Zetsche, M. Lavelle (2004). Particles and Nuclei. Springer. ISBN 3540201688. OCLC 53001447.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ W. Demtröder (2002). Atoms, Molecules and Photons: An Introduction to Atomic- Molecular- and Quantum Physics (1st Edition ed.). Springer. pp. 39–42. ISBN 3540206310.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - ^ F. Close (2006). The New Cosmic Onion. CRC Press. pp. p.82. ISBN 1584887982.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ D. Lincoln (2004). Understanding the Universe. World Scientific. pp. p.116. ISBN 9812387056.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ "Quarks". Antonine Education. Retrieved 2008-07-10.

- ^ B. Gal-Or (1983). Cosmology, Physics, and Philosophy. Springer. pp. p.276. ISBN 0387905812.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ J. S. Trefil, G. Walters (2004). The Moment of Creation. Courier Dover Publications. pp. p.112. ISBN 0486438139.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ B. A. Schumm (2004). Deep Down Things. JHU Press. pp. p.131–132. ISBN 080187971X. OCLC 55229065.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ A. Watson (2004). The Quantum Quark. Cambridge University Press. pp. p.286. ISBN 0521829070.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ a b c M. Veltman (2003). Facts and Mysteries in Elementary Particle Physics. World Scientific. pp. p.46. ISBN 981238149X.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ W. Weise, A. M. Green (1984). Quarks and Nuclei. World Scientific. pp. p.65. ISBN 9971966611.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ F. Canelli. "The Top Quark: Worth its Weight in Gold". University of Rochester. Retrieved 2008-10-24.

- ^ C. Amsler et al. (Particle Data Group), PL B667, 1 (2008) (URL: http://pdg.lbl.gov/2008/tables/rpp2008-sum-quarks.pdf)

- ^ T. Wu, W.-Y. Pauchy Hwang (1991). Relativistic quantum mechanics and quantum fields. World Science. pp. p. 321. ISBN 9810206089.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ D. Papenfuss, D. Lüst, W. Schleich (2002). 100 Years Werner Heisenberg: Works and Impact. Wiley-VCH. ISBN 3527403922. OCLC 50694495.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ P. Renton (1988). Electroweak Interactions. Cambridge University Press. p. 332. ISBN 0521366925.

- ^ C. Grupen, G. Cowan, S. D. Eidelman, T. Stroh (2005). Astroparticle Physics. Springer. pp. p.26. ISBN 3540253122.