Ain Silwan

The Ain Silwan ( Arabic عين سلوان, DMG ʿAin Silwān 'Silwan Source') ⊙ is a 15 m long and 5 m wide basin in Jerusalem, in which four Byzantine stumps stand.

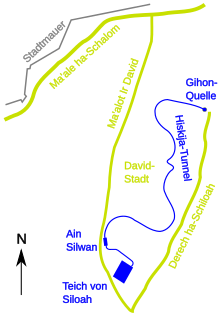

The Hezekiah tunnel coming from the Gihon spring ⊙ opens into the basin on the north side . The Hezekiah tunnel continues on the south side of the basin and flows into the pond of Siloam ( Arabic البركة الحمراء, DMG al-Birka al-Ḥamrāʾ 'red pond') ⊙ . This basin was formerly mistaken for the pool of Siloam.

It was a Christian pilgrimage site. The healing of the blind through Jesus was located here by the Christian tradition ( Jn 9 : 1-41 EU ) as was the passage in the Gospel of Luke that speaks of the tower of Siloam ( Lk 13.4 EU ). The Ain Silwan is also considered a holy source in Islam .

Next to the basin is the al-Ain mosque, built in 1890 ( Arabic المسجد العين, DMG al-Masǧid al-ʿAin 'Source Mosque'). The basin becomes Arabic بركة العين, DMG Birkat al-ʿAin called 'source pond'.

Surname

The name Ain Silwan is made up of Arabic عين, DMG ʿAin 'Quelle' and Silwan. The word Silwan comes from Hebrew שילוח Schiloach , German 'envoy, transmitter, (water) pipe' .

geography

The Ain Silwan is located about 400 m south of the old city of Jerusalem on theמעלות עיר דוד Ma'alot Ir David , German 'Stadt-David-Straße' .

history

The existence of the Gihon spring, which flows all year round, made it possible as early as the Copper Age 4500 BC. The settlement of people in the area. This settlement took place on the site of today's City of David ⊙ . No later than the 12th century BC. This settlement was surrounded by a defensive wall for protection. The need arose to have the water supply inside the city wall in the event of an attack. Around 800 BC The Hezekiah tunnel was dug that carried the water from the spring into the city. The water was now only taken from the end of this tunnel. In addition, they wanted to withdraw the water from the besieging enemies, so the access to the spring outside the wall was bricked up. So the actual source was forgotten and the Ain Silwan, ie the exit of the Hezekiah tunnel, was mistaken for a source.

Flavius Josephus described the Ain Silwan ( ancient Greek η altιλωα i Siloa , German 'the Siloah' ) in the 1st century as

"Sweet and abundant flowing spring"

It was also mentioned in the Mishnah as flowing water ( Sukka 4,5a. 10a), where its water was said to have a purifying effect. It played a role in the temple ceremony on the Feast of Tabernacles (Sukkah 4: 9-19).

Emperor Hadrian had a public bath built near the Ain Silwan in the 2nd century. It had a square fountain system with a side length of 22.5 m.

In 450 Empress Eudocia had a church built on this square. It had a dome and two separate pools of water. Her name was Our Savior, the Illuminator . This church was destroyed by the Persians in 614 . The column stumps that can be seen in the water basin come from this church from the Byzantine period. Because of them, this place is also called the Byzantine Pool of Siloam .

In 985 al-Muqaddasī mentions the Ain Silwan and in 1047 Nāsir-i Chusrau . The Ain Silwan is also mentioned in many crusader texts from the 12th century.

In 1280, Burchardus de Monte Sion described an aqueduct that leads from the Silwan spring (fons siloe, now called Gihon spring) to the upper Siloah basin. Here you can see that, as described under the point controversies, today's Gihon spring is called the Silwan spring.

The Gihon spring was rediscovered during an earthquake in the 16th century. In 1911, the entrance to the Hezekiah tunnel at the Ain Silwan was equipped with a round arch through which a tunnel inspection is possible.

Nowadays the Ain Silwan only carries a little water that is not drinkable.

Gihon Spring, Hezekiah Tunnel, Ain Silwan and Siloam Pond are located in a large archaeological park. The entrance to the park ⊙ is at the beginning of the Davidstadt Starting from Ophel ⊙ , the Jerusalem pilgrimage route is being excavated. It leads through a tunnel, which partly runs in a drainage channel from Herodian times , over the Ain Silwan to the pond of Siloam.

Controversy over name and location

As with so many places in Jerusalem and the surrounding area, the name and location of the Ain Silwan give rise to controversies between the various religious and political directions. Even the name and place are used and understood as the claim to power and territory of the various parties. Some archaeologists also feel obliged to their respective political-religious camps when characterizing their results.

Jewish-Israeli-Christian interpretation

According to the Judeo-Israeli-Christian view and interpretation of archaeological investigations, the Gihon spring is located about 300 m below the southeast corner of the Jerusalem city wall. The Gihon spring is identified with the Gihon spring often mentioned in the Bible ( Gen 2.13 EU , 2 Sam 5.7-8 EU , 1 Kings 1.33 EU , 2 Chr 33.14 EU , 2 Kings 20.20 EU , Neh 3.15 EU , all biblical information is geographically vague). The Hezekiah tunnel leads from the Gihon spring to the pond of Siloam. After 533 m, the Hezekiah tunnel reaches a 15 m long and 5 m wide basin, which was previously thought to be the pond of Siloam.

According to the Judeo-Israeli-Christian view, the Ain Silwan is located here. I.e. According to this view, the Ain Silwan is not a real source at all, but only the outflow of the Hezekiah tunnel. It is argued that the 800 BC The Hezekiah tunnel built in the 3rd century BC meant that the actual source, namely the Gihon spring, was forgotten until the 16th century and the mouth of the Hezekiah tunnel was believed to be a spring. This view is supported by the fact that the Al-Ain Mosque was built here at this mouth in 1890 and that this small pond was called the Al-Ain pond in Arabic. The name Ain Silwan, which is interpreted as the "source of the water pipe", is also used as an argument.

After this small pond, the Hezekiah tunnel continues 107 m to the actual pond of Siloam, which is also called the Red Pond .

Further names of the Gihon spring after this interpretation are:

- Arabic عين أم الدرج, DMG ʿAin Umm ad-Daraǧ , Mother's source by the stairs' because of the steps leading down to the source and because of the legend of the Virgin Mary.

- Arabic عين المعذراء, DMG ʿAin al-Maʿḏirāʾ 'Source of the Virgin'

- Arabic عين ستي مريم, DMG ʿAin Sittī Maryam 'Source of my mistress Maria'

(Explanation of the origin of these names under legends)

The names Gihonquelle, Hezekiah Tunnel (scientifically discovered and named in 1839), Davidstadt (the name Davidstadt was first proposed in 1920 and has been in use since 1970) come from the 19th and 20th centuries. They reflect a Judeo-Christian view of the situation and are based on the Judeo-Christian Bible.

Muslim-Palestinian interpretation

In Arabic and Palestinian literature, the Ain Silwan is sometimes equated with what is known today as the Gihon spring. What is now called the Gihon Spring is actually the Ain Silwan. The German Dominican Burchardus de Monte Sion also referred to the Gihon spring as the Silwan spring (fons siloe) in 1280. The two names Ain Umm al-Daraj and Ain al-Ma'azira are considered synonyms for Ain Silwan . Other publications name the Gihon spring with Ain Umm al-Daraj and the mouth of the Hezekiah tunnel with Ain Silwan or with pond Silwan .

According to the Muslim-Palestinian interpretation, the location of the biblical Gihon spring is unknown. This view is supported by the fact that at the end of the 19th century there were still several very different hypotheses among Christian archaeologists about where the Gihon spring could have been. Félix de Saulcy in 1853 and Ermete Pierotti suspected the Gihon spring north ⊙ of the Damascus Gate ⊙ in 1864 . In 1845 George Williams put forward the assumption that the Gihon spring is located near the southeast corner ⊙ of the Mamilla basin ⊙ . In 1865 and 1882 Félix de Saulcy agreed with this conjecture.

From the Muslim-Palestinian point of view, the names Gihonquelle, Hezekiah-Tunnel, Davidstadt are often an attempt to incorporate these places into the Judeo-Christian sphere of influence.

Traditions and Legends

The Ain Silwan was considered one of the four holiest springs in the world according to medieval Muslim tradition. Nāsir-i Chusrau lists the four most sacred springs in 1047: Ain al-Baqar in Akkon , Ain al-Falus in Bet She'an , Ain Silwan in Jerusalem and Ain Zamzam in Mecca . According to Islamic tradition, Allah saves the body of those who drink the water from one of these springs.

According to an Islamic legend, a person took a bucket of water from the Zamzam spring in Mecca and brought this water to Jerusalem, where he poured it into the Ain Silwan spring. With this he brought about a union of the two springs, so that the water from the Ain Silwan is now as sacred as the water from the Zamzam spring. Other legends even assume an underground connection between Ain Silwan and Zamzam.

Jews and Muslims consider the Ain Silwan to be one of the sources of paradise. The Ain Silwan is considered to be one of the springs from which al-Chidr drinks and in which he washes himself.

A Christian legend tells that the Virgin Mary washed the diapers and clothes of the baby Jesus in the Ain Silwan . Hence the names Source of the Mother by the Stairs , Mary's Source or Source of the Virgin .

Another name is mentioned in 1496 by Mujir ad-Din . Well of the accused women . He writes that pregnant Maria had to drink from it to prove her innocence.

See also

literature

- Vincent Lemire: La soif de Jérusalem , ED SORBONNE, 2011, ISBN 978-2859446598 download of the book as pdf possible

- Max Küchler : Jerusalem: A Handbook and Study Guide to the Holy City (Places and Landscapes of the Bible, Vol. IV, 2) , Publisher: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2007, ISBN 978-3-525-50170-2

Web links

- The "Gihon Spring" and "Hezekiah Tunnels" in Jerusalem

- Ayn Silwan short films show the Silwan source

- photos

- Photographs of the pool of Siloam

- News from science - map of the pond Siloah (via archive.org, as the original link leads to the spam page)

- items

- Siloam Inscriptions (May 15, 2002)

- Archaeologists Confirm Biblical Information About Siloam Tunnels (September 15, 2003)

- Is Everything in the Bible (November 2nd, 2003)

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Max Küchler : Jerusalem: A handbook and study travel guide to the Holy City. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2007, ISBN 978-3-525-50170-2 , pp. 11, 12, 13, 20, 57-73, 658, 730-746, 1041.

- ↑ a b c d e f Vincent Lemire: La soif de Jérusalem , ED SORBONNE, 2011, ISBN 978-2859446598 , pp. 14, 33, 50, 52, 53, 54, 56, 64, 66, 67, 74, 174 , 223, 310, 312, 465, 567, 568 download of the book as pdf possible at books.openedition.org. Retrieved May 12, 2020.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l The "Gihon source" and "Hezekiah tunnel" in Jerusalem at theologische-links.de. Retrieved June 26, 2020.

- ↑ Ayn Silwan at OSM. Retrieved June 26, 2020.

- ↑ Jewish War. Fourth chapter. Description of the city of Jerusalem. at wikisource.org. Retrieved June 26, 2020.

- ↑ Mishnah, Sukkah at archive.org. Retrieved June 26, 2020.

- ^ The Central Water Drainage Channel at cityofdavid.org.il. Retrieved June 26, 2020.

- ^ The New Herodian drainage channel in the City of David at allaboutjerusalem.com. Retrieved June 26, 2020.

- ↑ a b c d e Palestinian Authority: “Jerusalem never had a Jewish Temple” at jerusalemonline.com. Retrieved June 26, 2020.

- ↑ a b Wendy Pullan, Maximilian Sternberg, Lefkos Kyriacou, Craig Larkin, Michael Dumper: The Struggle for Jerusalem's Holy Places , Chapter 4: David's City in Palestinian Silwan , Routledge, 2013, ISBN 978-0-415-50536-9 , p . 76, 77 online

- ↑ Silwan Spring at enjoyjerusalem.com. Retrieved June 26, 2020.

- ^ Moshe Sharon: Corpus Inscriptionum Arabicarum Palaestinae: Volume One - A - , 1997, Brill, ISBN 978-9004108332 , p. 24 p. 24, Akko

- ↑ Musharraf b. Ibrahim al-Maqdisi: Fada'il Bayt al-Maqdis wa-al-Khalil wa Fada'il ash-Sham , Dar al-Mashriq, 1995, OCLC 729335131, p. 264